CBC

Wed, November 22, 2023

During the 2018 election campaign, PC leader Doug Ford promised to allow Ontario convenience stores to sell beer and wine. He has been unable to make that happen since becoming premier, in large part because of a contractual agreement between the province and the Beer Store that runs until the end of 2025.

(Cole Burston/Canadian Press - image credit)

Premier Doug Ford's government is preparing to change the rules on how beer, wine, cider and spirits are sold in Ontario, and there's plenty at stake — well beyond whether you'll be able to pick up a case at the corner store.

Industry officials expect the government's moves will affect how all types of alcohol are retailed.

The looming reforms also pit a range of interests against each other, as big supermarket companies, convenience store chains, the giant beer and wine producers, craft brewers and small wineries all vie for the best deal possible when Ontario's almost $10-billion-a-year retail landscape shifts.

As the negotiations proceed, the Ford government faces its own internal dilemma between its competing desires of giving the free market more control of booze sales vs. keeping LCBO revenues flowing into the provincial treasury.

The government has for months been engaged in closed-door consultations with industry players on what it calls "modernizing" the alcohol sales regime in Ontario.

For Ford's Progressive Conservatives, the chief goal is meeting a yet-to-be-fulfilled 2018 campaign promise to allow convenience stores to sell beer and wine. But multiple sources in various parts of the alcohol and retail industry say much more than that is on the table.

The LCBO turned a profit of nearly $2.5 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year, off $7.4 billion in gross revenue. (David Donnelly/CBC)

CBC News did lengthy interviews with eight people from across the beer, wine, spirits and retail sectors. All of them agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity, because the government required everyone involved in the consultations to sign non-disclosure agreements.

Here's what they say are the issues at stake:

Will the government shrink the LCBO's profit margins, including its take from products that other retailers sell?

Will retailers such as grocery and convenience stores be required to devote a certain amount of shelf space to Ontario-made beer and wine, or will they have total control over the inventory they stock?

Will small Ontario vineyards get any help in competing against big Ontario wineries whose products can contain as much as 75 per cent imported wine?

How big of a presence will the Beer Store maintain, and will it remain the only place Ontarians can bring back their empties for a deposit refund?

Will craft breweries be allowed to open more retail outlets, and will they get the tax cuts they're seeking?

Will spirits be part of the retail reform, including the sale of ready-to-drink products such as vodka coolers or hard seltzers in grocery and convenience stores?

Profit margins, markups, taxes

At its most fundamental level, much of the negotiations boils down to who gets the opportunity to make money off the various points of the alcohol supply chain, and how much.

"It's a lot of money at stake," said a source in the wine industry. "We're talking billions."

A person walks past an LCBO in Ottawa, Thursday March 19, 2020.

The LCBO operates 669 retail stores across Ontario. (Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press)

From $7.4 billion in sales in the 2022-23 fiscal year, the LCBO turned a profit of nearly $2.5 billion. Retailers, wineries and breweries are all hoping for a piece of that.

On a typical bottle of Ontario wine for instance, the producer currently gets roughly 30 to 45 per cent of the sticker price, according to industry officials.

The LCBO's own price calculators show it puts a 114 per cent retail markup on Ontario wine. One example shows wine supplied by a producer at $8.33 per bottle retailing for $22.30, once the markup, government levies and HST are added in.

Wine producers say the LCBO could afford to give a little on that markup, or the government could allow winemakers more opportunities to sell from their own retail outlets, so they get to keep the markup.

Craft brewers' biggest pricing concern is the impact of taxes. They say Ontario has the highest tax on craft beer of any province, a rate that is eight times higher than what's in effect in Quebec.

They also want the government to scrap the 9 cent environmental fee the province levies on each can of beer, which is different from the 10 cent deposit that consumers pay on a can.

Beer products are on display at a Beer Store outlet in Toronto.

Big brewery companies and small craft brewers want the Ontario government to reduce the province's beer taxes. (Chris Young/The Canadian Press)

Terminating Beer Store agreement

All sources expect the government to give notice by the end of December that it intends to terminate the contract that sets out the rules for beer sales in the province, known as the Master Framework Agreement (MFA), as also reported by The Toronto Star.

The latest version of the agreement, signed in 2015 between the then-Liberal government and the Beer Store, opened the door to beer and wine in Ontario supermarkets.

But it limits the number of grocery locations to 450, precludes them from selling anything larger than a six pack, and bars convenience stores from selling beer (although 7-Eleven has been approved for liquor licences for on-site consumption with food at nearly all of its Ontario stores).

The agreement will remain in effect until the end of 2025, so the termination notice "is just the starting gun" for a two-year transition to a more wide open retail market, says a source in the craft beer industry.

While sources are certain the government will terminate the agreement, they're uncertain about what will replace it.

"The MFA has never been about choice, convenience or prices for customers, it has always been about serving the interests of the big brewing conglomerates, and that's what needs to be addressed," said Michelle Wasylyshen, spokesperson for the Retail Council of Canada, whose board of directors includes members from Loblaw, Sobeys, Metro, Walmart and Costco.

People line up in a parking lot for a long wait to return empties or buy beer at a Beer Store in downtown Toronto on April 16, 2020.

Industry sources expect the government will give notice by the end of December that it intends to terminate the Master Framework Agreement between the province and the Beer Store. The current version of the agreement, signed in 2015, allows 450 supermarkets in the province to sell beer but precludes them from selling any formats larger than a six pack. (Colin Perkel/The Canadian Press)

More retail outlets

While Ontario's current regulations limit who can sell alcohol as a retailer, and in what formats, the limits on the biggest players in the industry are far less strict than what small breweries and wineries face.

Wine Rack has 164 locations. It is part of Arterra Wines Canada, the company that owns such wineries as Jackson-Triggs, Inniskillin and Sandbanks.

The Wine Shop (100 locations) is part of Andrew Peller Ltd., the company that owns such wineries as Peller Estates, Trius and Wayne Gretzky Estates.

By contrast, each craft brewery can only have two retail outlets, and both must be attached to a production facility. Each small winery can only have one retail outlet, located where it grows grapes and makes wine.

Both the craft beer and small winery sectors want those restrictions scrapped.

"If anybody thinks the government is politically hurt by picking fights with large corporations, they're very wrong," said a source in the wine industry.

A sign over the wine aisle at Save-On-Foods grocery store in Richmond, British Columbia pictured on Thursday July 11, 2019.

Ontario wineries are looking to supermarkets to do more to promote local wineries, like this grocery store does in Richmond, B.C. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

Rules for supermarkets

Those same regulations governing retail outlets also set down the rules for the 450 grocery store locations that are permitted to sell beer, wine or cider.

Sources say the big supermarket chains are pushing the government to lift some of the restrictions that dictate how they can and can't sell products.

"I think the biggest concern is, what is 'big grocery' going to get at the table?" said another wine industry source. "The industry just wants to make sure there are programs and supports in place if they're going to compete in an open market."

Under the current rules, supermarkets must ensure that at least 20 per cent of beer and cider on display and 10 per cent of wine comes from small producers. Local producers would like to see assurances of more shelf space devoted to "made in Ontario" products.

The rules also prohibit supermarkets from charging brewers and wineries any listing or stocking fees to put their products on the shelves (as is the practice with many ordinary grocery items). Craft brewers and small wineries want that ban kept in place.

The current rules ban the supermarket chains from selling any brands of beer or wine in which they have "direct or indirect financial interest."

That stops Costco, for instance, from selling its own private-label Kirkland Signature wine in Ontario, and would prevent other supermarket chains from launching their own beer or wine products. Industry insiders are wondering if the government will scrap that rule.

Malivoire winery, in Beamsville, Ont., on June 29, 2020.

Under Ontario's current rules, at least 10 per cent of the wine on display in supermarkets must be produced by small wineries. (Evan Mitsui/CBC)

Big wine versus small wine

If the new retail landscape allows the supermarket chains free rein over their inventory, Ontario wineries are worried they'll get pushed off the store shelves by imports.

"Retail expansion must be done right or else it threatens the future of Ontario wine and further supports heavily subsidized, foreign wineries," said a joint report issued in May by Wine Growers Ontario (big producers) and Ontario Craft Wineries (small producers).

Those two groups don't always see eye to eye on the issues, in part because a significant portion of the wine sold by Ontario's biggest wine producers isn't actually made in Ontario. These "international domestic blends" contain up to 75 per cent imported wine and are sold under the label of some of Ontario's best known vineyards.

"The market is dominated by big companies," says a source who runs a small winery. "It's David and Goliath."

The source says it's challenging for small wineries to have much presence in LCBO locations, which means the major brands become the biggest sellers, and in turn grocery stores are reluctant to stock wines that don't already have big brand recognition.

"This should be a political no-brainer to be on our side," said the source. "We've got to hope the premier sees it that way, that we are the little guys and he has the opportunity to help a domestic industry."

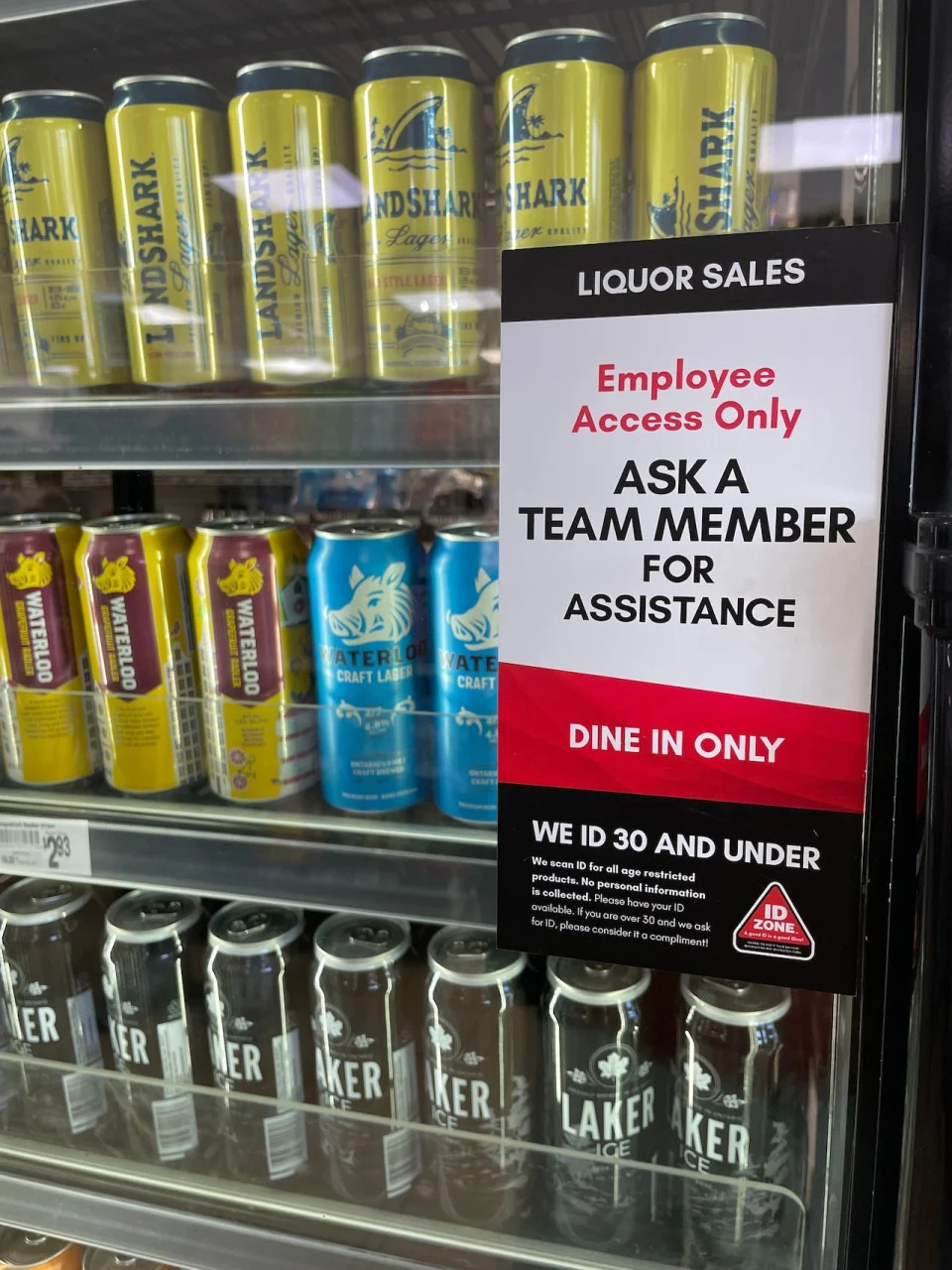

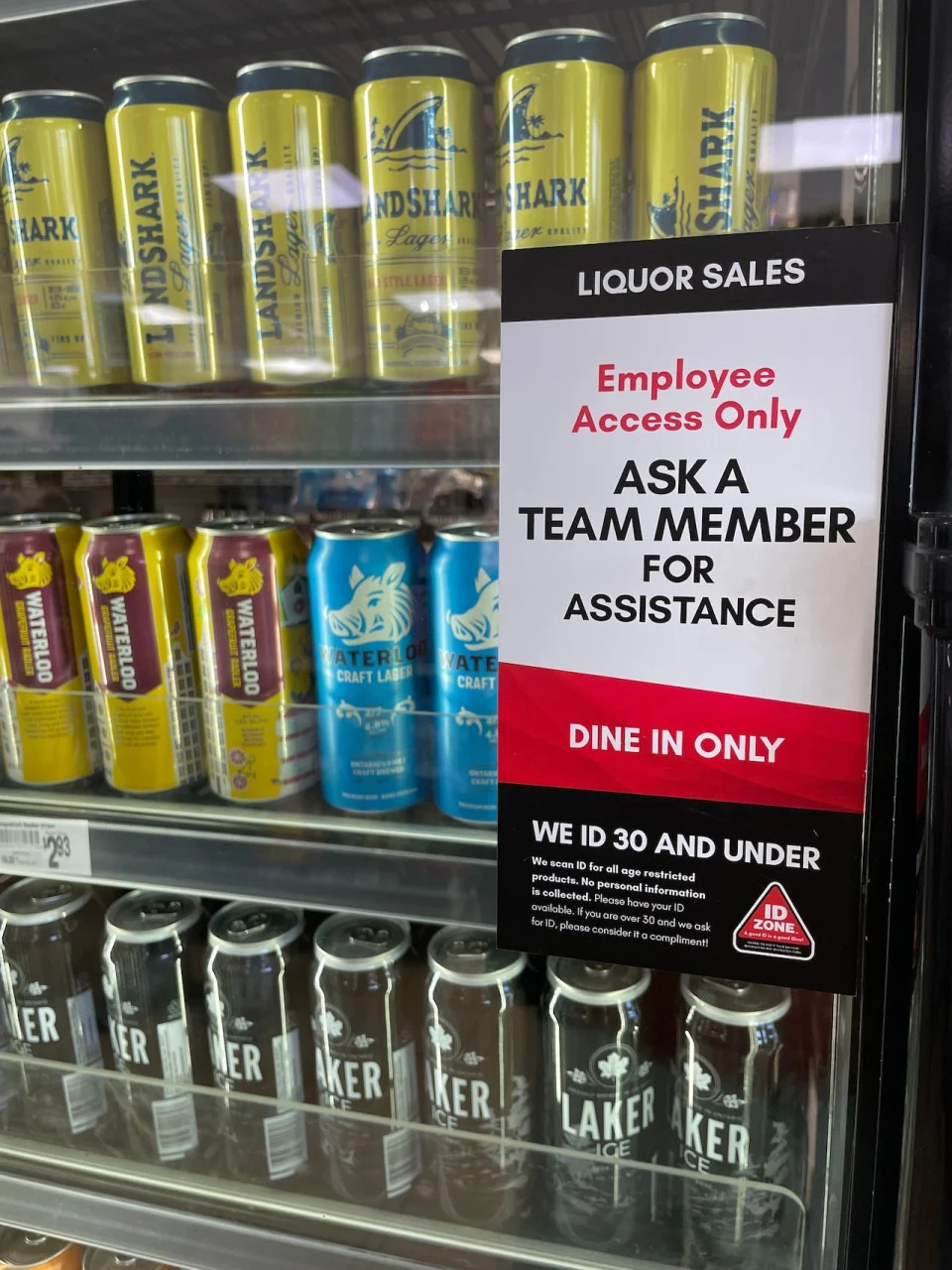

7-Eleven has been approved for licences to serve alcohol for on-site consumption at nearly all of its stores in Ontario. So far, licences have actually been issued and sales commenced at only two of the convenience store chain's locations, in Leamington and Niagara Falls, pictured here.

7-Eleven has been approved for licences to serve alcohol for on-site consumption at nearly all of its stores in Ontario. As of July 2023, sales had commenced at only two of the convenience store chain's locations, in Leamington and Niagara Falls. (Pelin Sidki/CBC)

Convenience stores

When Ford made his campaign promise to allow corner stores to sell beer and wine, he ignored the fact that doing so would have put the province on the hook to the big brewers for hundreds of millions of dollars, under the terms of the Master Framework Agreement.

That's why the government backed away from the plan, and waited until that contract with the Beer Store got closer to its expiration date. The timing actually works out to be politically convenient for Ford's PCs: it sets the stage for beer and wine in the corner stores in early 2026, just before the next election, scheduled for June that year.

Convenience stores are confident the government will make good on the promise, but they have some concerns about the price structure they will face.

"Margins are going to be the biggest factor," says a convenience store industry source. "The LCBO is the biggest barrier right now. The LCBO handling fee is just so high."

In Quebec, where stores negotiate directly with brewers, the source says the profit margin on beer in convenience stores averages 18 per cent, far more than what Ontario grocery stores currently take in.

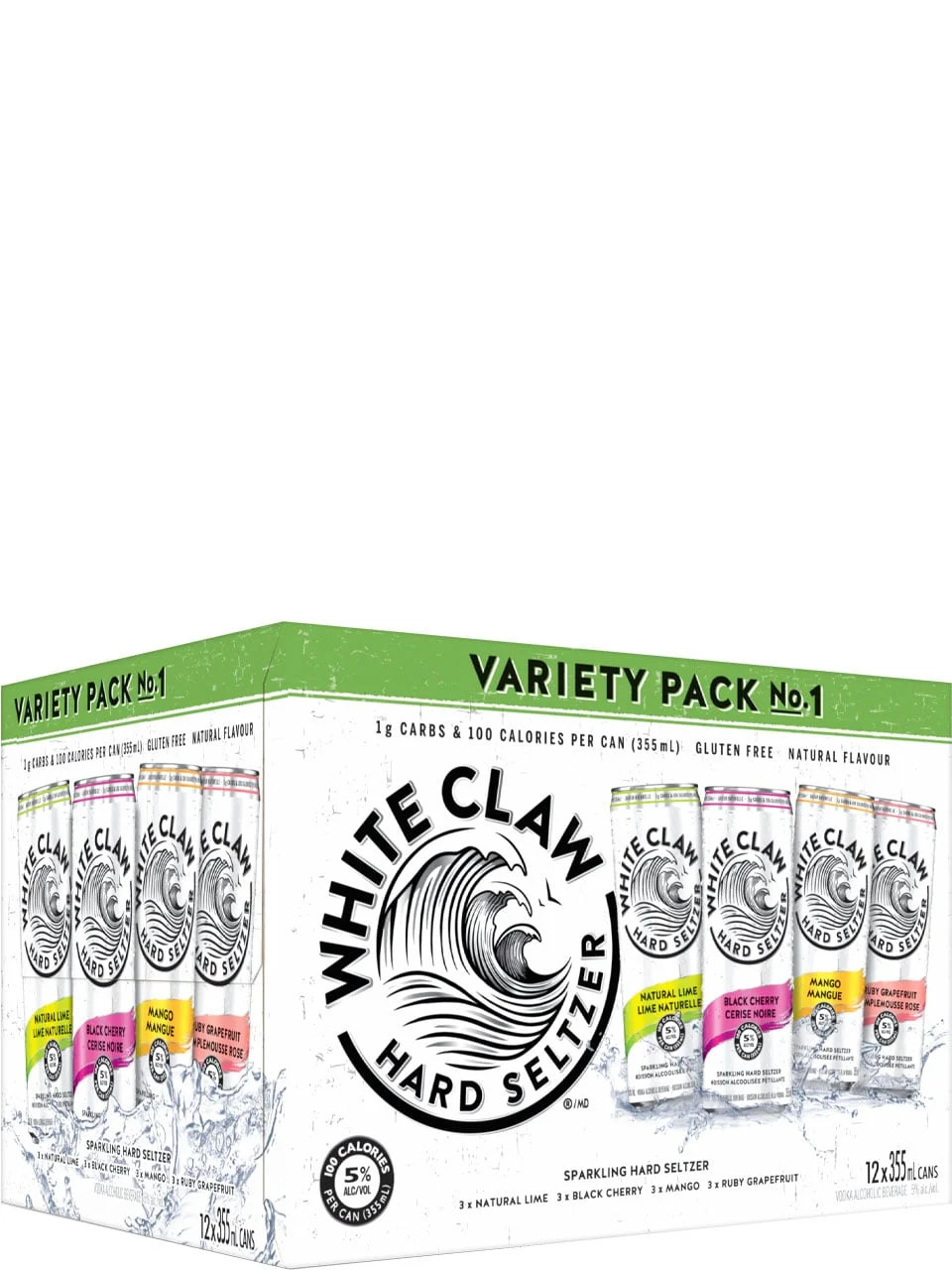

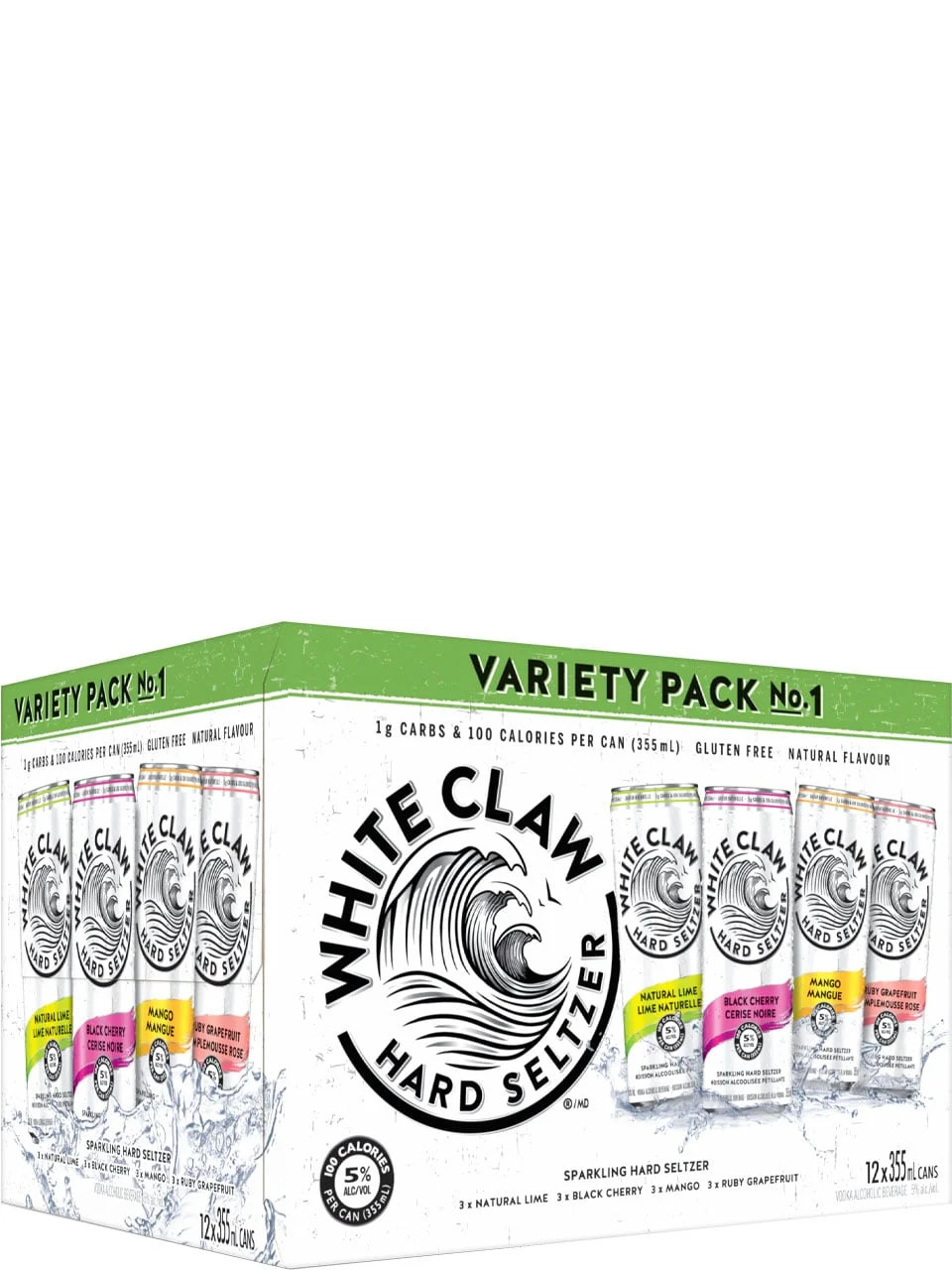

The companies that produce pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, such as coolers and hard seltzers, want their products to be available for purchase in Ontario grocery and convenience stores. (Newfoundland Labrador Liquor Corp.)

Spirits and ready-to-drink beverages

Much of the debate in Ontario about liquor retailing centres on how beer and wine are sold, often leaving spirits out of the equation.

While distillers aren't necessarily looking to sell bottles of vodka, whisky and rum from convenience stores, they are seeking more equitable treatment as the province reforms its alcohol retail laws.

"It's a big job, 100 years of Prohibition-era regulations that need to be untangled," says a source in the spirits industry.

Distillers are seeing growth in the sales of pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, such as hard seltzers and coolers. Their position is that these ready-to-drink items are similar to beer and cider in size, packaging and alcohol content, so should be treated no differently at the retail level.

Right now, the only retailer where you can buy these products is the LCBO. The industry wants them made available in grocery and convenience stores.

"In a place where you can buy beer, wine and cannabis in privately run stores, it's kind of weird that you can only buy spirits in a government-run store," said the source.

The alcohol retail market in Ontario totalled $9.8 billion in 2021-22, according to Statistics Canada. (Evan Mitsui/CBC)

Wholesaling and distribution

While the average consumer is aware that the producer and the retailer of booze get a share of the sticker price, there's also money to be made in wholesaling and distribution.

The LCBO and the Beer Store have a stranglehold on distribution right now. Both the supermarket chains and the convenience store industry want that loosened.

"Preventing a monopoly on distribution is in the best interest of Ontarians and convenience retailers across the province," says the Convenience Industry Council of Canada in a statement.

"All of the major wholesale distributors in Ontario should be allowed to distribute alcohol from manufacturers to convenience store locations."

A source with one of the major breweries counters that the Beer Store has distribution down to a fine art.

"It's really difficult to see how any other entity would do it and not increase the price of beer," said the source.

Premier Doug Ford's government is preparing to change the rules on how beer, wine, cider and spirits are sold in Ontario, and there's plenty at stake — well beyond whether you'll be able to pick up a case at the corner store.

Industry officials expect the government's moves will affect how all types of alcohol are retailed.

The looming reforms also pit a range of interests against each other, as big supermarket companies, convenience store chains, the giant beer and wine producers, craft brewers and small wineries all vie for the best deal possible when Ontario's almost $10-billion-a-year retail landscape shifts.

As the negotiations proceed, the Ford government faces its own internal dilemma between its competing desires of giving the free market more control of booze sales vs. keeping LCBO revenues flowing into the provincial treasury.

The government has for months been engaged in closed-door consultations with industry players on what it calls "modernizing" the alcohol sales regime in Ontario.

For Ford's Progressive Conservatives, the chief goal is meeting a yet-to-be-fulfilled 2018 campaign promise to allow convenience stores to sell beer and wine. But multiple sources in various parts of the alcohol and retail industry say much more than that is on the table.

The LCBO turned a profit of nearly $2.5 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year, off $7.4 billion in gross revenue. (David Donnelly/CBC)

CBC News did lengthy interviews with eight people from across the beer, wine, spirits and retail sectors. All of them agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity, because the government required everyone involved in the consultations to sign non-disclosure agreements.

Here's what they say are the issues at stake:

Will the government shrink the LCBO's profit margins, including its take from products that other retailers sell?

Will retailers such as grocery and convenience stores be required to devote a certain amount of shelf space to Ontario-made beer and wine, or will they have total control over the inventory they stock?

Will small Ontario vineyards get any help in competing against big Ontario wineries whose products can contain as much as 75 per cent imported wine?

How big of a presence will the Beer Store maintain, and will it remain the only place Ontarians can bring back their empties for a deposit refund?

Will craft breweries be allowed to open more retail outlets, and will they get the tax cuts they're seeking?

Will spirits be part of the retail reform, including the sale of ready-to-drink products such as vodka coolers or hard seltzers in grocery and convenience stores?

Profit margins, markups, taxes

At its most fundamental level, much of the negotiations boils down to who gets the opportunity to make money off the various points of the alcohol supply chain, and how much.

"It's a lot of money at stake," said a source in the wine industry. "We're talking billions."

A person walks past an LCBO in Ottawa, Thursday March 19, 2020.

The LCBO operates 669 retail stores across Ontario. (Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press)

From $7.4 billion in sales in the 2022-23 fiscal year, the LCBO turned a profit of nearly $2.5 billion. Retailers, wineries and breweries are all hoping for a piece of that.

On a typical bottle of Ontario wine for instance, the producer currently gets roughly 30 to 45 per cent of the sticker price, according to industry officials.

The LCBO's own price calculators show it puts a 114 per cent retail markup on Ontario wine. One example shows wine supplied by a producer at $8.33 per bottle retailing for $22.30, once the markup, government levies and HST are added in.

Wine producers say the LCBO could afford to give a little on that markup, or the government could allow winemakers more opportunities to sell from their own retail outlets, so they get to keep the markup.

Craft brewers' biggest pricing concern is the impact of taxes. They say Ontario has the highest tax on craft beer of any province, a rate that is eight times higher than what's in effect in Quebec.

They also want the government to scrap the 9 cent environmental fee the province levies on each can of beer, which is different from the 10 cent deposit that consumers pay on a can.

Beer products are on display at a Beer Store outlet in Toronto.

Big brewery companies and small craft brewers want the Ontario government to reduce the province's beer taxes. (Chris Young/The Canadian Press)

Terminating Beer Store agreement

All sources expect the government to give notice by the end of December that it intends to terminate the contract that sets out the rules for beer sales in the province, known as the Master Framework Agreement (MFA), as also reported by The Toronto Star.

The latest version of the agreement, signed in 2015 between the then-Liberal government and the Beer Store, opened the door to beer and wine in Ontario supermarkets.

But it limits the number of grocery locations to 450, precludes them from selling anything larger than a six pack, and bars convenience stores from selling beer (although 7-Eleven has been approved for liquor licences for on-site consumption with food at nearly all of its Ontario stores).

The agreement will remain in effect until the end of 2025, so the termination notice "is just the starting gun" for a two-year transition to a more wide open retail market, says a source in the craft beer industry.

While sources are certain the government will terminate the agreement, they're uncertain about what will replace it.

"The MFA has never been about choice, convenience or prices for customers, it has always been about serving the interests of the big brewing conglomerates, and that's what needs to be addressed," said Michelle Wasylyshen, spokesperson for the Retail Council of Canada, whose board of directors includes members from Loblaw, Sobeys, Metro, Walmart and Costco.

People line up in a parking lot for a long wait to return empties or buy beer at a Beer Store in downtown Toronto on April 16, 2020.

Industry sources expect the government will give notice by the end of December that it intends to terminate the Master Framework Agreement between the province and the Beer Store. The current version of the agreement, signed in 2015, allows 450 supermarkets in the province to sell beer but precludes them from selling any formats larger than a six pack. (Colin Perkel/The Canadian Press)

More retail outlets

While Ontario's current regulations limit who can sell alcohol as a retailer, and in what formats, the limits on the biggest players in the industry are far less strict than what small breweries and wineries face.

Wine Rack has 164 locations. It is part of Arterra Wines Canada, the company that owns such wineries as Jackson-Triggs, Inniskillin and Sandbanks.

The Wine Shop (100 locations) is part of Andrew Peller Ltd., the company that owns such wineries as Peller Estates, Trius and Wayne Gretzky Estates.

By contrast, each craft brewery can only have two retail outlets, and both must be attached to a production facility. Each small winery can only have one retail outlet, located where it grows grapes and makes wine.

Both the craft beer and small winery sectors want those restrictions scrapped.

"If anybody thinks the government is politically hurt by picking fights with large corporations, they're very wrong," said a source in the wine industry.

A sign over the wine aisle at Save-On-Foods grocery store in Richmond, British Columbia pictured on Thursday July 11, 2019.

Ontario wineries are looking to supermarkets to do more to promote local wineries, like this grocery store does in Richmond, B.C. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

Rules for supermarkets

Those same regulations governing retail outlets also set down the rules for the 450 grocery store locations that are permitted to sell beer, wine or cider.

Sources say the big supermarket chains are pushing the government to lift some of the restrictions that dictate how they can and can't sell products.

"I think the biggest concern is, what is 'big grocery' going to get at the table?" said another wine industry source. "The industry just wants to make sure there are programs and supports in place if they're going to compete in an open market."

Under the current rules, supermarkets must ensure that at least 20 per cent of beer and cider on display and 10 per cent of wine comes from small producers. Local producers would like to see assurances of more shelf space devoted to "made in Ontario" products.

The rules also prohibit supermarkets from charging brewers and wineries any listing or stocking fees to put their products on the shelves (as is the practice with many ordinary grocery items). Craft brewers and small wineries want that ban kept in place.

The current rules ban the supermarket chains from selling any brands of beer or wine in which they have "direct or indirect financial interest."

That stops Costco, for instance, from selling its own private-label Kirkland Signature wine in Ontario, and would prevent other supermarket chains from launching their own beer or wine products. Industry insiders are wondering if the government will scrap that rule.

Malivoire winery, in Beamsville, Ont., on June 29, 2020.

Under Ontario's current rules, at least 10 per cent of the wine on display in supermarkets must be produced by small wineries. (Evan Mitsui/CBC)

Big wine versus small wine

If the new retail landscape allows the supermarket chains free rein over their inventory, Ontario wineries are worried they'll get pushed off the store shelves by imports.

"Retail expansion must be done right or else it threatens the future of Ontario wine and further supports heavily subsidized, foreign wineries," said a joint report issued in May by Wine Growers Ontario (big producers) and Ontario Craft Wineries (small producers).

Those two groups don't always see eye to eye on the issues, in part because a significant portion of the wine sold by Ontario's biggest wine producers isn't actually made in Ontario. These "international domestic blends" contain up to 75 per cent imported wine and are sold under the label of some of Ontario's best known vineyards.

"The market is dominated by big companies," says a source who runs a small winery. "It's David and Goliath."

The source says it's challenging for small wineries to have much presence in LCBO locations, which means the major brands become the biggest sellers, and in turn grocery stores are reluctant to stock wines that don't already have big brand recognition.

"This should be a political no-brainer to be on our side," said the source. "We've got to hope the premier sees it that way, that we are the little guys and he has the opportunity to help a domestic industry."

7-Eleven has been approved for licences to serve alcohol for on-site consumption at nearly all of its stores in Ontario. So far, licences have actually been issued and sales commenced at only two of the convenience store chain's locations, in Leamington and Niagara Falls, pictured here.

7-Eleven has been approved for licences to serve alcohol for on-site consumption at nearly all of its stores in Ontario. As of July 2023, sales had commenced at only two of the convenience store chain's locations, in Leamington and Niagara Falls. (Pelin Sidki/CBC)

Convenience stores

When Ford made his campaign promise to allow corner stores to sell beer and wine, he ignored the fact that doing so would have put the province on the hook to the big brewers for hundreds of millions of dollars, under the terms of the Master Framework Agreement.

That's why the government backed away from the plan, and waited until that contract with the Beer Store got closer to its expiration date. The timing actually works out to be politically convenient for Ford's PCs: it sets the stage for beer and wine in the corner stores in early 2026, just before the next election, scheduled for June that year.

Convenience stores are confident the government will make good on the promise, but they have some concerns about the price structure they will face.

"Margins are going to be the biggest factor," says a convenience store industry source. "The LCBO is the biggest barrier right now. The LCBO handling fee is just so high."

In Quebec, where stores negotiate directly with brewers, the source says the profit margin on beer in convenience stores averages 18 per cent, far more than what Ontario grocery stores currently take in.

The companies that produce pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, such as coolers and hard seltzers, want their products to be available for purchase in Ontario grocery and convenience stores. (Newfoundland Labrador Liquor Corp.)

Spirits and ready-to-drink beverages

Much of the debate in Ontario about liquor retailing centres on how beer and wine are sold, often leaving spirits out of the equation.

While distillers aren't necessarily looking to sell bottles of vodka, whisky and rum from convenience stores, they are seeking more equitable treatment as the province reforms its alcohol retail laws.

"It's a big job, 100 years of Prohibition-era regulations that need to be untangled," says a source in the spirits industry.

Distillers are seeing growth in the sales of pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, such as hard seltzers and coolers. Their position is that these ready-to-drink items are similar to beer and cider in size, packaging and alcohol content, so should be treated no differently at the retail level.

Right now, the only retailer where you can buy these products is the LCBO. The industry wants them made available in grocery and convenience stores.

"In a place where you can buy beer, wine and cannabis in privately run stores, it's kind of weird that you can only buy spirits in a government-run store," said the source.

The alcohol retail market in Ontario totalled $9.8 billion in 2021-22, according to Statistics Canada. (Evan Mitsui/CBC)

Wholesaling and distribution

While the average consumer is aware that the producer and the retailer of booze get a share of the sticker price, there's also money to be made in wholesaling and distribution.

The LCBO and the Beer Store have a stranglehold on distribution right now. Both the supermarket chains and the convenience store industry want that loosened.

"Preventing a monopoly on distribution is in the best interest of Ontarians and convenience retailers across the province," says the Convenience Industry Council of Canada in a statement.

"All of the major wholesale distributors in Ontario should be allowed to distribute alcohol from manufacturers to convenience store locations."

A source with one of the major breweries counters that the Beer Store has distribution down to a fine art.

"It's really difficult to see how any other entity would do it and not increase the price of beer," said the source.

No comments:

Post a Comment