Nakul Krishna

Tue, 6 February 2024

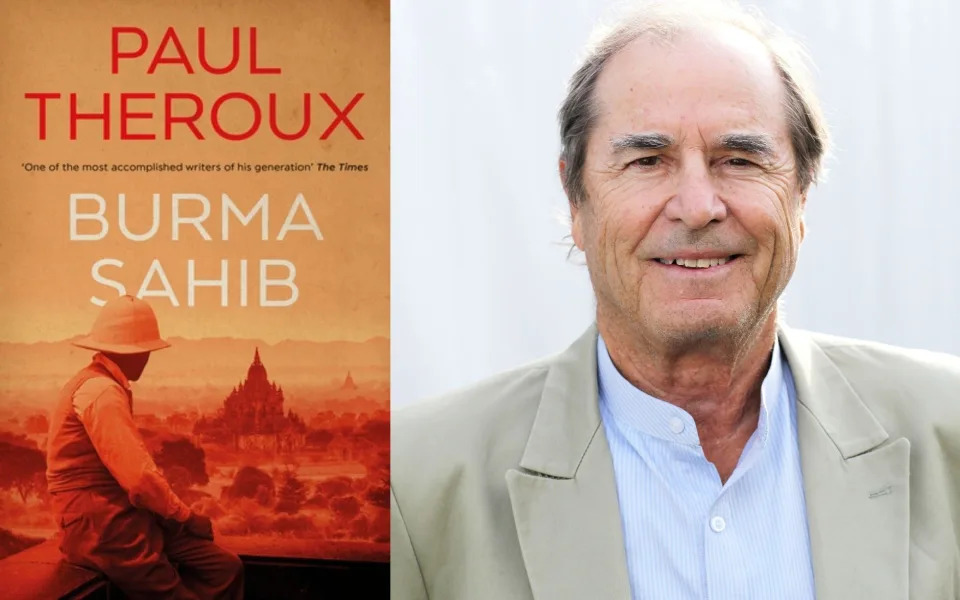

Burma Sahib is Paul Theroux's 30th novel - Hamish Hamilton

Paul Theroux’s 30th novel, about George Orwell’s years as a policeman in Burma, is part of a well-populated genre: Tan Twan Eng on Somerset Maugham in Malaysia, Colm Tóibín on Thomas Mann in America, Damon Galgut on EM Forster in India. Burma Sahib also joins the many books published last year to mark the 120th anniversary of Orwell’s birth, of which the ones that have provoked the most attention are DJ Taylor’s Orwell: The New Life and Anna Funder’s Wifedom, the latter a decidedly unsympathetic portrait of Orwell as husband.

Theroux’s Orwell, 19 years old when the book begins, is a more likeable figure. He still goes by the name his parents gave him: Eric Arthur Blair. Not long out of Eton, he opts for the Imperial Police over university, and in 1922 ships out to Burma, full of romantic notions acquired from Kipling. Orwell ends up serving there for a little over five years, over which period he acquires the sense of writerly vocation and the anti-imperialist political convictions that make it impossible for him to carry on.

Orwell’s time in Burma was the basis for at least three pieces of published writing. The longest of them, the 1934 novel Burmese Days, is gripping, if a trifle melodramatic. If Theroux’s speculations are right, that novel’s main character John Flory is a composite of real figures whom Orwell knew in Burma. The two widely anthologised essays that drew on Orwell’s Burmese experiences – ‘A Hanging’ and ‘Shooting an Elephant’ – are the basis of two of Theroux’s best chapters. (The veracity of the latter essay has been questioned, but Theroux evidently believes that Orwell’s famous account of the episode was substantially true.)

Beyond that, even Taylor’s dense biography admits that “much of Orwell’s time in the East is shrouded in mystery”. But the mystery gives Theroux just the gaps he needs for a story that is both credible as history and enjoyable as fiction. Theroux’s Blair has many of the traits of the more familiar mature Orwell, chief among them a desire not to be thought eccentric.

Despite his growing cynicism about the imperial project, some of his bitterest thoughts are directed at the “pansy Left”, whose convictions about the evils of imperialism betray their ignorance of the violence and disorder of Burmese society. And even as he obeys his superiors’ orders, Orwell is cultivating a secret inner life, fed by his reading (Kipling, Wells, Maugham, London, Huxley, Forster and Lawrence), his study of Asian languages, and his careful attention to his tropical surroundings, as he learns to tell a peepul tree from a neem, a teak from a tamarind.

George Orwell - ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Theroux is not shy about probing into Orwell’s private life. Taylor’s biography stops at noting that the unpublished poetry from those years suggest that “bought sex was a subject of which Orwell possessed a more-than-abstract knowledge”. Theroux is much less coy. His Blair, a teenager struggling to grow a moustache when the book begins, manages to sustain multiple sexual relationships with his Burmese housemaids, the “tarts” at local brothels, and the well-read wife of a fellow colonial.

The prose in these passages courts embarrassment (“her perfumed breasts, and the slippery tang of her sex”). And while Theroux’s ear for English speech is generally acute, there are moments of anachronism and Americanism: would a young man steeped in the language and literature of an English public school really use the word “snitch” rather than “sneak”?

But against these lapses we must hold up Theroux’s many fine passages. Here, for instance, is young Orwell being woken up by the crowing of a rooster: “the morning sun slatted through the bamboo blinds and gilding the folds of his mosquito net”. And here is Orwell taking in the full sensory blast of Rangoon: “the tickle of manure, as the street was thick with horse-drawn carts; the reek of sweat from the soaked backs of hurrying barefoot man pulling rickshaws… the stink of hot oil and burnt food.” Admirers of Theroux’s travel writing will find many such examples of his old capacity for precise lyricism – restrained, no doubt, by Orwell’s own stern example.

Burma Sahib is published by Hamish Hamilton at £20. To order your copy for £16.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books

No comments:

Post a Comment