SPACE

What happens if you fall into a black hole? NASA simulations provide an answer.

Tue, May 7, 2024

Anyone who has watched Matthew McConaughey plunge into a supermassive black hole in "Interstellar" may think they have a rough idea of what it'd be like to encounter one of these terrifying cosmic formations.

But a Hollywood blockbuster set decades in the future is no comparison to the real thing – even if it was directed by Christopher Nolan. Ten years after "Interstellar" hit theaters, NASA is now giving us a more personal experience of what would happen if we were to fall into a black hole.

No, not even the most intrepid spacefarers are yet able to get anywhere near these massive behemoths, where the pull of gravity is so intense that even light doesn't have enough energy to escape their grasp.

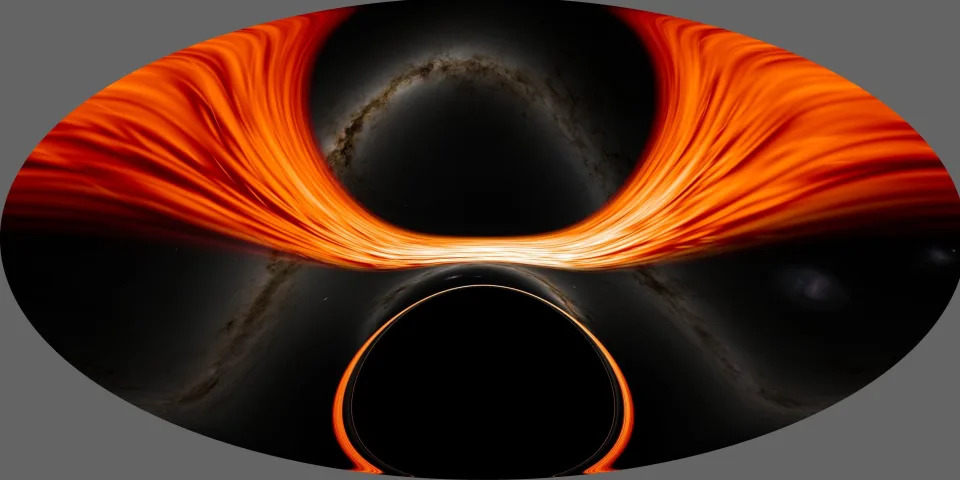

In the meantime, simulations released Monday instead simply imagine what a person may see while plummeting toward a black hole's event horizon to their inevitable death. Yet another simulation released by NASA shows the imagined point of view of an astronaut flying past a black hole as space appears to bend and morph.

"I simulated two different scenarios, one where a camera – a stand-in for a daring astronaut – just misses the event horizon and slingshots back out, and one where it crosses the boundary, sealing its fate," said Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland who produced the visualizations.

Available on YouTube, the four visualizations include explanations to guide viewers on what they're witnessing and include 360-versions to allow viewers to look around during the virtual trip.

NASA simulations show plunge into black hole

While humanity has learned much more about black holes in recent years since the first one was identified in 1964, the objects remain notoriously mysterious.

NASA's new visualizations, available on Goddard's YouTube page, erase some of that enigma. The two visualizations are divided into one-minute trips rendered as 360-degree videos that allow viewers to look around during the trip, and extended versions with explanations to guide viewers on what they're witnessing.

The destination of the simulation is a virtual supermassive black hole with a mass 4.3 million times that of Earth's sun, a size equivalent to the monster Sagittarius A* located at the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

A new immersive visualization produced on a NASA supercomputer shows viewers what it would be like to plunge into a black hole.

The first simulation shows the viewer approaching the black hole from around 400 million miles away and rapidly falling toward the event horizon – a theoretical boundary known as the "point of no return" where light and other radiation can no longer escape. Like Sagittarius A*, the event horizon of the simulation spans about 16 million miles.

Cloud structures called photon rings and a flat, swirling cloud of hot, glowing gas called an accretion disk surrounding the black hole serve as a visual reference during the fall. As the camera reaches the speed of light, the accretion disc becomes more distorted as space-time warps.

Once inside the black hole itself, the viewer rushes toward the black hole's one-dimensional center called a singularity, where the laws of physics as we know them cease to exist.

The simulations were made using the Discover supercomputer at the NASA Center for Climate Simulation, and generated around 10 terabytes of data, which is about half of the estimated text content in the Library of Congress.

Second simulation shows viewer narrowly escaping black hole

Astronomers divide black holes into three general categories based on mass: stellar-mass, supermassive, and intermediate-mass.

Stellar-mass black holes, which form when a star with more than eight times the sun’s mass runs out of fuel and its core explodes as a supernova, are even less ideal to find yourself falling into than its supermassive counterpart, Schnittman explained.

“If you have the choice, you want to fall into a supermassive black hole,” Schnittman said in a statement. “Stellar-mass black holes, which contain up to about 30 solar masses, possess much smaller event horizons and stronger tidal forces, which can rip apart approaching objects before they get to the horizon.”

This occurs because the gravitational pull on the end of an object nearer the black hole is much stronger than that on the other end. Falling objects stretch out like noodles, a process astrophysicists call spaghettification. For this simulated black hole, it would only take about 12.8 seconds for the viewer to meet their end by spaghettification.

The alternate simulation shows a viewer orbiting close to the event horizon but escaping to safety before ever crossing it.

If an astronaut flew a spacecraft on this 6-hour round trip, the explorer would return 36 minutes younger than those who remained on a mothership far away, NASA explained. This is another concept that will be familiar to "Interstellar" fans and is due to time passing more slowly near a strong gravitational source.

"This situation can be even more extreme," Schnittman said. "If the black hole were rapidly rotating, like the one shown in the 2014 movie 'Interstellar,' (the astronaut) would return many years younger than her shipmates."

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for USA TODAY. Reach him at elagatta@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: NASA simulations show what it would be like to fall in black hole: Video

Steve Gorman

Updated Tue, May 7, 2024

A United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket stands on the pad the day after a launch attempt of two astronauts aboard Boeing's Starliner-1 Crew Flight Test (CFT) was delayed, in Cape Canaveral

By Steve Gorman

(Reuters) -The Atlas V rocket carrying Boeing Co's new Starliner space capsule will be rolled back to its hangar to replace a pressure valve, postponing the long-awaited first crewed test flight of the spacecraft for at least 10 more days, NASA said on Tuesday.

The new targeted launch date for the mission - pivotal to Boeing's struggle to acquire a greater share of lucrative NASA business now dominated by Elon Musk's SpaceX - has been set for May 17 at the earliest, according to NASA.

The debut flight of the CST-100 Starliner with astronauts aboard was originally scheduled for liftoff on Monday night from NASA's Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a voyage to the International Space Station (ISS).

But the launch was called off with less than two hours left in the countdown after a pressure regulation valve malfunctioned on the upper-stage liquid oxygen tank of the Atlas rocket as it was being readied for blastoff.

The rocket, a separate component from the Starliner capsule, is furnished and operated by United Launch Alliance (ULA), a Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture.

Once launched, the gumdrop-shaped capsule and its two-astronaut crew are expected remain docked to the space station for about a week before returning to Earth in a parachute- and airbag-assisted landing in the U.S. Desert Southwest.

Selected to ride aboard Starliner on its first crewed run, and to operate its manual controls, were two veteran NASA astronauts with 500 hours of spaceflight between them - Barry "Butch" Wilmore, 61, and Sunita "Suni" Williams, 58.

After Monday night's aborted launch attempt, NASA, Boeing and ULA announced that they would seek to try again as early as Friday, May 10.

But in an update posted Tuesday evening, NASA said more time was needed after ULA "decided to remove and replace" the pressure valve, whose irregular fluctuations appeared to be beyond adjustment. That will require the rocket to be rolled back to its vertical integration facility on Wednesday for repairs, leak checks and other reviews ahead of a second launch attempt, NASA said.

Those operations pushed the potential launch date back at least another week from the earlier target, NASA said.

The crewed space launch comes two years after the Starliner completed its first test flight to the orbital laboratory without humans aboard. The Starliner's first uncrewed flight to the ISS in 2019 ended in failure.

Boeing has faced intense public scrutiny of all its activities after a series of safety failures that have staggered its commercial airplane operations, including the mid-air blowout of a jetliner door plug in January.

The company has been eager to get its Starliner space venture off the ground to show signs of success and redeem a program years behind schedule, and with more than $1.5 billion in cost overruns.

While Boeing has struggled, SpaceX has become a dependable taxi to orbit for NASA, which is backing a new generation of privately built spacecraft to ferry astronauts to the ISS and, under the space agency's more ambitious Artemis program, to the moon and eventually Mars.

(Reporting by Steve Gorman in Los Angeles; Editing by Christian Schmollinger and Gerry Doyle)

Agence France-Presse

May 7, 2024

Astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams were set to blast off at 10:34 pm Monday (0234 GMT Tuesday) -- clad in Boeing's bright blue spacesuits, the pair had waved goodbye to their families before boarding a van to the launch tower(AFP)

The first crewed flight of Boeing's Starliner spaceship was dramatically called off around two hours before launch after a new safety issue was identified, officials said Monday, pushing back a high-stakes test mission to the International Space Station.

Astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams were strapped in their seats preparing for liftoff when the call for a "scrub" came, in order to give engineers time to investigate unusual readings from an oxygen relief valve on the second stage of the rocket.

"Standing down on tonight's attempt to launch," tweeted NASA chief Bill Nelson. "As I've said before, @NASA's first priority is safety. We go when we're ready."

The next possible launch date comes on Tuesday night, but it wasn't immediately clear how big the problem was and if it could be resolved with the rocket still on the launchpad. NASA said it would hold a late night press briefing to provide updates.

The mission has already faced years of delays and comes at a challenging time for Boeing, as a safety crisis engulfs the century-old manufacturer's commercial aviation division.

'NASA is banking on a successful test for Starliner so it can certify a second commercial vehicle to carry crews to the ISS.

Elon Musk's SpaceX achieved the feat with its Dragon capsule in 2020, ending a nearly decade-long dependence on Russian rockets following the end of the Space Shuttle program.

Clad in Boeing's bright blue spacesuits, the astronauts were helped out of the spaceship then boarded a van to leave the launch tower at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, returning to their quarters.

Wilmore and Williams, both Navy-trained pilots and space program veterans, have each been to the ISS twice, traveling once on a shuttle and then aboard a Russian Soyuz vessel.

Hiccups expected

When it launches, Starliner will be propelled into orbit by an Atlas V rocket made by United Launch Alliance, a Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture. The crew will then take the helm, piloting the craft manually to test its capabilities.

The gumdrop-shaped capsule with a cabin about as roomy as an SUV is then set to rendezvous with the ISS for a weeklong stay.

Williams and Wilmore will conduct a series of tests to verify Starliner's functionality before returning to Earth for a parachute-assisted landing in the western United States.

A successful mission would help dispel the bitter taste left by numerous setbacks in the Starliner program.

In 2019, during a first uncrewed test flight, software defects meant the capsule was not placed on the right trajectory and returned without reaching the ISS. "Ground intervention prevented loss of vehicle," said NASA in the aftermath, chiding Boeing for inadequate safety checks.

Then in 2021, with the rocket on the launchpad for a new flight, blocked valves forced another postponement.

The vessel finally reached the ISS in May 2022 in a non-crewed launch. But other problems that came to light -- including weak parachutes and flammable tape in the cabin that needed to be removed -- caused further delays to the crewed test flight, necessary for the capsule to be certified for NASA use on regular ISS missions.

Exclusive club

SpaceX's Dragon capsule joined that exclusive club four years ago, following the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Space Shuttle programs.

In 2014, the agency awarded fixed-price contracts of $4.2 billion to Boeing and $2.6 billion to SpaceX to develop the capsules under its Commercial Crew Program.

This marked a shift in NASA's approach from owning space flight hardware to instead paying private partners for their services as the primary customer.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk took a swipe at Boeing, gloating that his company "finished 4 years sooner" despite receiving a smaller contract. He attributed Boeing's delay to "too many non-technical managers" in a post on X.

Once Starliner is fully operational, NASA hopes to alternate between SpaceX and Boeing vessels to taxi humans to the ISS.

Even though the orbital lab is due to be mothballed in 2030, both Starliner and Dragon could be used for future private space stations that several companies are developing.

© Agence France-Presse

Hubble views a galaxy with a voracious black hole

IMAGE:

THIS NASA HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE IMAGE FEATURES THE SPIRAL GALAXY NGC 4951, LOCATED ROUGHLY 50 MILLION LIGHT-YEARS AWAY FROM EARTH.

CREDIT: NASA, ESA, AND D. THILKER (THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY); IMAGE PROCESSING: GLADYS KOBER (NASA/CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA)

Venus has almost no water. A new study may reveal why

IMAGE:

VENUS TODAY IS DRY THANKS TO WATER LOSS TO SPACE AS ATOMIC HYDROGEN. IN THE DOMINANT LOSS PROCESS, AN HCO+ ION RECOMBINES WITH AN ELECTRON, PRODUCING SPEEDY H ATOMS (ORANGE) THAT USE CO MOLECULES (BLUE) AS A LAUNCHPAD TO ESCAPE.

view moreCREDIT: AURORE SIMONNET / LABORATORY FOR ATMOSPHERIC AND SPACE PHYSICS / UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER

Planetary scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder have discovered how Venus, Earth’s scalding and uninhabitable neighbor, became so dry.

The new study fills in a big gap in what the researchers call “the water story on Venus.” Using computer simulations, the team found that hydrogen atoms in the planet’s atmosphere go whizzing into space through a process known as “dissociative recombination”—causing Venus to lose roughly twice as much water every day compared to previous estimates.

The team will publish their findings May 6 in the journal Nature.

The results could help to explain what happens to water in a host of planets across the galaxy.

“Water is really important for life,” said Eryn Cangi, a research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) and co-lead author of the new paper. “We need to understand the conditions that support liquid water in the universe, and that may have produced the very dry state of Venus today.”

Venus, she added, is positively parched. If you took all the water on Earth and spread it over the planet like jam on toast, you’d get a liquid layer roughly 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) deep. If you did the same thing on Venus, where all the water is trapped in the air, you’d wind up with only 3 centimeters (1.2 inches), barely enough to get your toes wet.

“Venus has 100,000 times less water than the Earth, even though it’s basically the same size and mass,” said Michael Chaffin, co-lead author of the study and a research scientist at LASP.

In the current study, the researchers used computer models to understand Venus as a gigantic chemistry laboratory, zooming in on the diverse reactions that occur in the planet’s swirling atmosphere. The group reports that a molecule called HCO+ (an ion made up of one atom each of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen) high in Venus’ atmosphere may be the culprit behind the planet’s escaping water.

For Cangi, co-lead author of the research, the findings reveal new hints about why Venus, which probably once looked almost identical to Earth, is all but unrecognizable today.

“We’re trying to figure out what little changes occurred on each planet to drive them into these vastly different states,” said Cangi, who earned her doctorate in astrophysical and planetary sciences at CU Boulder in 2023.

Spilling the water

Venus, she noted, wasn’t always such a desert.

Scientists suspect that billions of year ago during the formation of Venus, the planet received about as much water as Earth. At some point, catastrophe struck. Clouds of carbon dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere kicked off the most powerful greenhouse effect in the solar system, eventually raising temperatures at the surface to a roasting 900 degrees Fahrenheit. In the process, all of Venus’ water evaporated into steam, and most drifted away into space.

But that ancient evaporation can’t explain why Venus is as dry as it is today, or how it continues to lose water to space.

“As an analogy, say I dumped out the water in my water bottle. There would still be a few droplets left,” Chaffin said.

On Venus, however, almost all of those remaining drops also disappeared. The culprit, according to the new work, is elusive HCO+.

Missions to Venus

Chaffin and Cangi explained that in planetary upper atmospheres, water mixes with carbon dioxide to form this molecule. In previous research, the researchers reported that HCO+ may be responsible for Mars losing a big chunk of its water.

Here’s how it works on Venus: HCO+ is produced constantly in the atmosphere, but individual ions don’t survive for long. Electrons in the atmosphere find these ions, and recombine to split the ions in two. In the process, hydrogen atoms zip away and may even escape into space entirely—robbing Venus of one of the two components of water.

In the new study, the group calculated that the only way to explain Venus’ dry state was if the planet hosted larger than expected volumes of HCO+ in its atmosphere. There is one twist to the team’s findings. Scientists have never observed HCO+ around Venus. Chaffin and Cangi suggest that’s because they’ve never had the instruments to properly look.

While dozens of missions have visited Mars in recent decades, far fewer spacecraft have traveled to the second planet from the sun. None have carried instruments capable of detecting the HCO+ that powers the team’s newly discovered escape route.

“One of the surprising conclusions of this work is that HCO+ should actually be among the most abundant ions in the Venus atmosphere,” Chaffin said.

In recent years, however, a growing number of scientists have set their sights on Venus. NASA’s planned Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (DAVINCI) mission, for example, will drop a probe through the planet’s atmosphere all the way to the surface. It’s scheduled to launch by the end of the decade.

DAVINCI won’t be able to detect HCO+, either, but the researchers are hopeful that a future mission might—revealing another key piece of the story of water on Venus.

“There haven’t been many missions to Venus,” Cangi said. “But newly planned missions will leverage decades of collective experience and a flourishing interest in Venus to explore the extremes of planetary atmospheres, evolution and habitability.”

JOURNAL

Nature

ARTICLE TITLE

Venus water loss is dominated by HCO+ dissociative recombination

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

6-May-2024

A triumph of galaxies in three new images from the VST

Reports and ProceedingsIMAGE:

ESO 510-G13, A CURIOUS LENTICULAR GALAXY ABOUT 150 MILLION LIGHT YEARS FROM US, IN THE DIRECTION OF THE HYDRA CONSTELLATION.

view moreCREDIT: INAF/VST. ACKNOWLEDGMENT: M. SPAVONE (INAF), R. CALVI (INAF)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Distant, far away galaxies. Interacting galaxies, whose shape has been forged by the mutual gravitational influence, but also galaxies forming groups and clusters, kept together by gravity. They are the protagonists of three new images released by the VLT Survey Telescope (VST).

VST is an optical telescope with a 2,6 diameter mirror, entirely built in Italy, that has been operating since 2011 at the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Paranal Observatory in Chile. Since 2022, the telescope has been fully managed by INAF through the National Coordination Centre for VST, based at the INAF premises in Naples. VST is specialised in observing large areas of the sky thanks to its wide field camera, OmegaCAM, an actual “cosmic wide-angle lens” able to capture, in each shot, one square degree of the sky, a portion of the celestial vault twice as large as the full Moon’s apparent diameter on each side. Besides images for astrophysics research, spanning from stars to galaxies all the way to cosmology, in the past year the telescope has conducted a new programme dedicated to the general public, observing nebulae, galaxies and other iconic objects during some full Moon nights, when the brightness of our natural satellite disturbs the collection of scientific data. More images will be published in the coming months.

“Besides scientific research, one of the goals of the VST Centre is to disseminate scientific knowledge and to share the wonders of the Universe with the general public. We especially wish that young people can discover and nurture their interest in astrophysics through these amazing images”, notes Enrichetta Iodice, INAF researcher in Naples and responsible for the national Coordination Centre for VST.

One of the three new images portrays ESO 510-G13, a curious lenticular galaxy about 150 million light years from us, in the direction of the Hydra constellation. The central bulge of the galaxy stands out. The dark silhouette of the dust disk, seen from the edge, crosses the bulge, obscuring part of the light. The disk’s distorted shape, vaguely resembling an upside-down S, indicates the turbulent past of ESO 510-G13, which may have acquired its current appearance following a collision with another galaxy. In the lower right corner, among the many stars of the Milky Way scattered across the image, a pair of spiral galaxies about 250 million light years from us are also visible. Zooming into the image, many more galaxies appear, even at greater distances, as small spots of light elongated among the many dots in the background.

The second image shows a small group of four galaxies, called Hickson Compact Group 90 (HGC 90), which is about 100 million light years away from Earth, towards the Piscis Austrinus constellation. The two round, bright spots near the image centre are the elliptical galaxies NGC 7173 and NGC 7176. The bright streak that bifurcates and connects these two galaxies is the third member of the group, the spiral galaxy NGC 7174: its curious shape indicates the ongoing interaction between the three celestial bodies, which has stripped their stars and gas, mixing up their distribution. A halo of diffuse light envelops the three galaxies. The fourth galaxy belonging to the group, NGC 7172, visible in the upper part of the image, does not seem to participate in this celestial dance: its core, crossed by dark clouds of dust, hides a supermassive black hole that has been actively devouring the surrounding material. The HGC 90 quartet of galaxies is embedded in a much larger structure, including dozens of galaxies, some of which are visible in this image.

The third image shows a much richer and even more distant grouping of galaxies: the Abell 1689 galaxy cluster, which can be observed in the direction of the Virgo constellation. Abell 1689 contains more than two hundred galaxies, mostly visible as yellow-orange blobs, whose light has travelled for about two billion years before reaching the VST. The enormous mass, including enormous quantities of hot gas and of the mysterious dark matter in addition to the galaxies, deforms space-time in the vicinity of the cluster. Therefore, the cluster acts as a “gravitational lens” on more distant galaxies, amplifying their light and producing distorted images, much like what a magnifying glass does. Some of these galaxies can be spotted as dots and tiny, slightly curved lines, especially around the cluster's central regions.

A small group of four galaxies, called Hickson Compact Group 90 (HGC 90), which is about 100 million light years away from Earth, towards the Piscis Austrinus constellation.

CREDIT

INAF/VST/VEGAS, E. Iodice (INAF). Acknowledgment: M. Spavone (INAF), R. Calvi (INAF)

The Abell 1689 galaxy cluster, which can be observed in the direction of the Virgo constellation.

CREDIT

INAF/VST. Acknowledgment: M. Spavone (INAF), R. Calvi (INAF)

For further information:

Visit the VST website: https://vst.inaf.it/

Contacts:

INAF Press Office - Marco Galliani, +39 335 1778428, ufficiostampa@inaf.it

MIT astronomers observe elusive stellar light surrounding ancient quasars

The observations suggest some of earliest “monster” black holes grew from massive cosmic seeds

IMAGE:

A JAMES WEBB TELESCOPE IMAGE SHOWS THE J0148 QUASAR CIRCLED IN RED. TWO INSETS SHOW, ON TOP, THE CENTRAL BLACK HOLE, AND ON BOTTOM, THE STELLAR EMISSION FROM THE HOST GALAXY.

view moreCREDIT: COURTESY OF MINGHAO YUE, ANNA-CHRISTINA EILERS; NASA

MIT astronomers have observed the elusive starlight surrounding some of the earliest quasars in the universe. The distant signals, which trace back more than 13 billion years to the universe’s infancy, are revealing clues to how the very first black holes and galaxies evolved.

Quasars are the blazing centers of active galaxies, which host an insatiable supermassive black hole at their core. Most galaxies host a central black hole that may occasionally feast on gas and stellar debris, generating a brief burst of light in the form of a glowing ring as material swirls in toward the black hole.

Quasars, by contrast, can consume enormous amounts of matter over much longer stretches of time, generating an extremely bright and long-lasting ring — so bright, in fact, that quasars are among the most luminous objects in the universe.

Because they are so bright, quasars outshine the rest of the galaxy in which they reside. But the MIT team was able for the first time to observe the much fainter light from stars in the host galaxies of three ancient quasars.

Based on this elusive stellar light, the researchers estimated the mass of each host galaxy, compared to the mass of its central supermassive black hole. They found that for these quasars, the central black holes were much more massive relative to their host galaxies, compared to their modern counterparts.

The findings, published today in the Astrophysical Journal, may shed light on how the earliest supermassive black holes became so massive despite having a relatively short amount of cosmic time in which to grow. In particular, those earliest monster black holes may have sprouted from more massive “seeds” than more modern black holes did.

“After the universe came into existence, there were seed black holes that then consumed material and grew in a very short time,” says study author Minghao Yue, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “One of the big questions is to understand how those monster black holes could grow so big, so fast.”

“These black holes are billions of times more massive than the sun, at a time when the universe is still in its infancy,” says study author Anna-Christina Eilers, assistant professor of physics at MIT. “Our results imply that in the early universe, supermassive black holes might have gained their mass before their host galaxies did, and the initial black hole seeds could have been more massive than today.”

Eilers’ and Yue’s co-authors include MIT Kavli Director Robert Simcoe, MIT Hubble Fellow and postdoc Rohan Naidu, and collaborators in Switzerland, Austria, Japan, and at North Carolina State University.

Dazzling cores

A quasar’s extreme luminosity has been obvious since astronomers first discovered the objects in the 1960s. They assumed then that the quasar’s light stemmed from a single, star-like “point source.” Scientists designated the objects “quasars,” as a portmanteau of a “quasi-stellar” object. Since those first observations, scientists have realized that quasars are in fact not stellar in origin but emanate from the accretion of intensely powerful and persistent supermassive black holes sitting at the center of galaxies that also host stars, which are much fainter in comparison to their dazzling cores.

It’s been extremely challenging to separate the light from a quasar’s central black hole from the light of the host galaxy’s stars. The task is a bit like discerning a field of fireflies around a central, massive searchlight. But in recent years, astronomers have had a much better chance of doing so with the launch of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which has been able to peer farther back in time, and with much higher sensitivity and resolution, than any existing observatory.

In their new study, Yue and Eilers used dedicated time on JWST to observe six known, ancient quasars, intermittently from the fall of 2022 through the following spring. In total, the team collected more than 120 hours of observations of the six distant objects.

“The quasar outshines its host galaxy by orders of magnitude. And previous images were not sharp enough to distinguish what the host galaxy with all its stars looks like,” Yue says. “Now for the first time, we are able to reveal the light from these stars by very carefully modeling JWST’s much sharper images of those quasars.”

A light balance

The team took stock of the imaging data collected by JWST of each of the six distant quasars, which they estimated to be about 13 billion years old. That data included measurements of each quasar’s light in different wavelengths. The researchers fed that data into a model of how much of that light likely comes from a compact “point source,” such as a central black hole’s accretion disk, versus a more diffuse source, such as light from the host galaxy’s surrounding, scattered stars.

Through this modeling, the team teased apart each quasar’s light into two components: light from the central black hole’s luminous disk and light from the host galaxy’s more diffuse stars. The amount of light from both sources is a reflection of their total mass. The researchers estimate that for these quasars, the ratio between the mass of the central black hole and the mass of the host galaxy was about 1:10. This, they realized, was in stark contrast to today’s mass balance of 1:1,000, in which more recently formed black holes are much less massive compared to their host galaxies.

“This tells us something about what grows first: Is it the black hole that grows first, and then the galaxy catches up? Or is the galaxy and its stars that first grow, and they dominate and regulate the black hole’s growth?” Eilers explains. “We see that black holes in the early universe seem to be growing faster than their host galaxies. That is tentative evidence that the initial black hole seeds could have been more massive back then.”

“There must have been some mechanism to make a black hole gain their mass earlier than their host galaxy in those first billion years,” Yue adds. “It’s kind of the first evidence we see for this, which is exciting.”

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News

JOURNAL

The Astrophysical Journal

ARTICLE TITLE

“EIGER V. Characterizing the Host Galaxies of Luminous Quasars at z ≳ 6”

No comments:

Post a Comment