Trump’s Bagram Push: Recasting Afghanistan In Global Strategy – Analysis

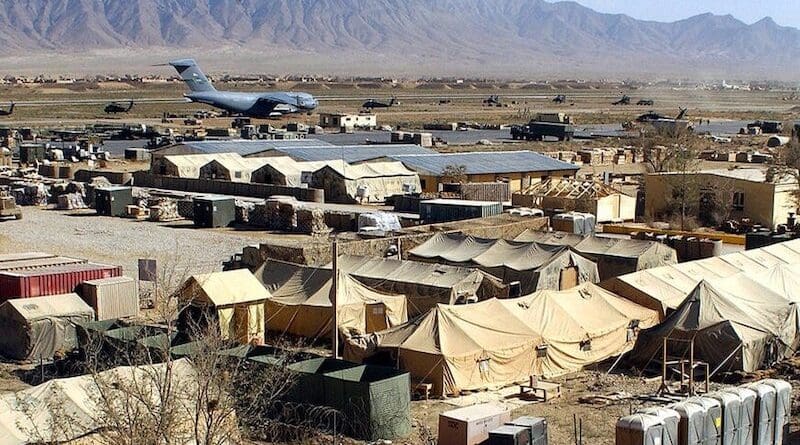

File photo of Bagram military base in Afghanistan. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

By Observer Research Foundation

By Kabir Taneja

The President of the United States (US), Donald Trump, has recently returned to one of his old standing demands, insisting that the sprawling Bagram military base—which lies around 65 km from Afghanistan’s capital Kabul—be returned to American control. Trump took to social media and said ‘bad things’ will happen if the Taliban refuses to hand over the facility.

In response, the Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid said that Afghanistan will never hand over Bagram or any Afghan territory to a foreign power, whether it is the US or China. Trump has argued that Bagram lies in proximity to Beijing’s nuclear weapons facilities, turning the demand into an irredeemable position from the perspective of American security.

Bagram was indeed the core American base for 20 years as the US military struggled during its war against Al Qaeda—and by association, the Taliban—in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attack. The Soviets—under the reign of Monarch Zahir Shah in Kabul during the 1950s—were the original architects of the Bagram base. It was only in the 1980s that the Soviets withdrew from it, and following the initiation of America’s ‘war on terror’ campaign in 2001, Bagram became central to its military power in the country.

However, the Bagram saga is not just about Trump’s self-professed view to tackle the Chinese threat with this move. It brings in a larger set of regional challenges that have been playing out since August 2021, when a dramatic and chaotic American military withdrawal was orchestrated from Bagram under the auspices of then-President Joe Biden. The last US soldier left on board a US Air Force C-17 transport aircraft on 30 August 2021, as Afghanistan was handed back to the Taliban, marking the end of the two-decade-long war, which ultimately led nowhere.

The US exit, however, was a geopolitical boon for Iran, China, and Russia. While Trump has relayed his interests in China’s nuclear files as the primary motivator in the Bagram base demands, the US is not the most influential state exerting pressure on the Taliban anymore. While the Trump administration does hold significant sway over sanctions and the frozen finances Afghanistan has overseas, the Taliban, almost half a decade into power, has managed to establish virtually complete control across the state without any major hiccups or internal political challenges. Nonetheless, its domestic fabric remains fragile, and tensions with neighbours are consistent.

Trump’s recent bonhomie with Pakistan and its Prime Minister (PM) Shehbaz Sharif, who has taken to fully ingratiating the US president in exchange for reimagining Islamabad’s presence in the White House, is in part aimed at Afghanistan as well. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an iteration of the Taliban movement, has consistently targeted Pakistani security interests over the past few years. Pakistan has blamed the Afghan Taliban for giving refuge to TTP. On the other hand, the Afghan Taliban says the TTP is Pakistan’s internal security matter. The Pakistani intelligence, once the father figure of the Taliban, is at odds with its own protégé today.

Within this fracas, enter Iran. While Tehran’s geopolitical capacities today are concentrated on the Middle East file, its ‘other borders’, largely calm, allow it to deploy its limited military capacities towards issues such as Israel, Gaza, and its nuclear politics with the West. Any return of Western military to Afghanistan will be unacceptable to Tehran. Iran has prepared for such contingencies by strengthening relations with the Taliban over the past two decades despite its fundamental aversion to the group. Iranian security would be directly threatened, as would Russia and China, if the US succeeds in getting Bagram back. Moreover, Iran will do everything within its power to prevent this eventuality.

For the Taliban itself, allowing any foreign power to base in Afghanistan will be impossible to sell to the group’s rank and file. After 20 years of bloodshed and now enjoying a narrative of having defeated the only superpower in the world, allowing American basing would be akin to shooting yourself in the foot. Before the fall of Kabul, reports and rumours alike were rife that the Taliban was benefiting from American help in eliminating the rise of the Islamic State Khorasan (ISKP) in some of the country’s restive provinces, with the group being seen as a challenge to international security. The fact that ISKP openly opposed the Talibanafforded the latter the bizarre opportunity to present itself as a counter-terror actor. This had already caused some unease within the then government of President Ashraf Ghani, who found themselves on a slippery slope as the US and Taliban signed an exit agreement under the first Trump presidency.

Irrespective of strategic cognisance and potential economic windfalls the Taliban could gain for their struggling economy, the Taliban, after roughly two years of internal wrangling, has come to somewhat of a conclusion on how its internal power is distributed as it moves from militancy to governance. The ideological clique led by Emir Hibatullah Akhundzada, based in Kandahar, has control over most matters of governance today, including foreign policy, which was more in the hands of Kabul, led by Sirajuddin Haqqani of the infamous Haqqani Network. Pragmatism over ideology as a potential concept to further Afghanistan’s cause has been discarded.

Trump’s push for Bagram will lead nowhere unless it is accompanied by military coercion. The option by itself is unpalatable to the American politics of today, coupled with diplomatic capacities being tied down by conflicts such as Ukraine and Gaza. However, if the Trump administration erratically decides to pursue a kinetic option to secure Bagram, many of the regional powers contesting the US directly, christened by some as the ‘Axis of Upheaval’, would make Afghanistan a sectarian and ethnic battleground once again to make sure it remains politically unavailable while weaponising the trauma of the Afghan war ultimately going the Taliban’s way for Western populations.

- About the author: Kabir Taneja is a Deputy Director and Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

- Source: This article was published at the Observer Research Foundation.

Observer Research Foundation

ORF was established on 5 September 1990 as a private, not for profit, ’think tank’ to influence public policy formulation. The Foundation brought together, for the first time, leading Indian economists and policymakers to present An Agenda for Economic Reforms in India. The idea was to help develop a consensus in favour of economic reforms.

No comments:

Post a Comment