Young American’s first-hand account of second opium war: bloody battles and ‘hospitable’ Chinese

The journals of George Washington (Farley) Heard, who would go on to become chairman of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, (HSBC) reveal what happened when he found himself caught between Anglo-French forces and Chinese defenders in 1859

Gillian Bickley 19 Apr, 2018 Post Magazine / Books

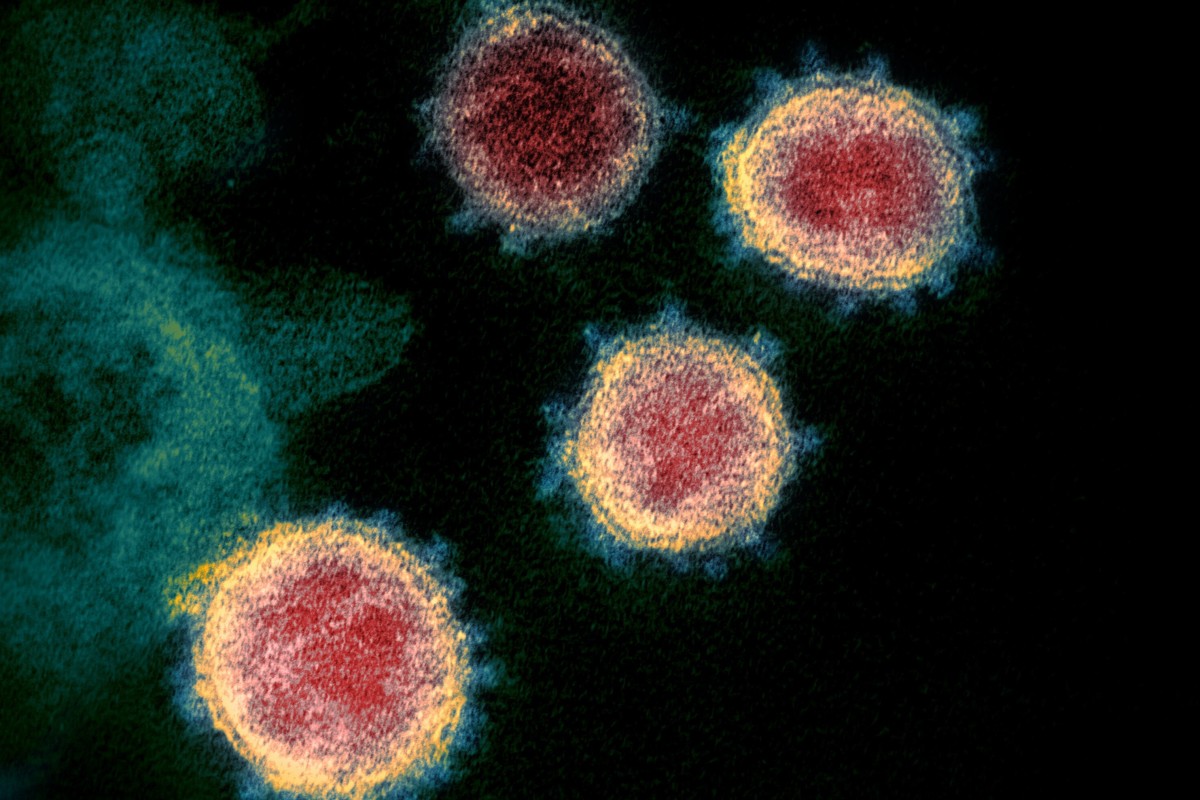

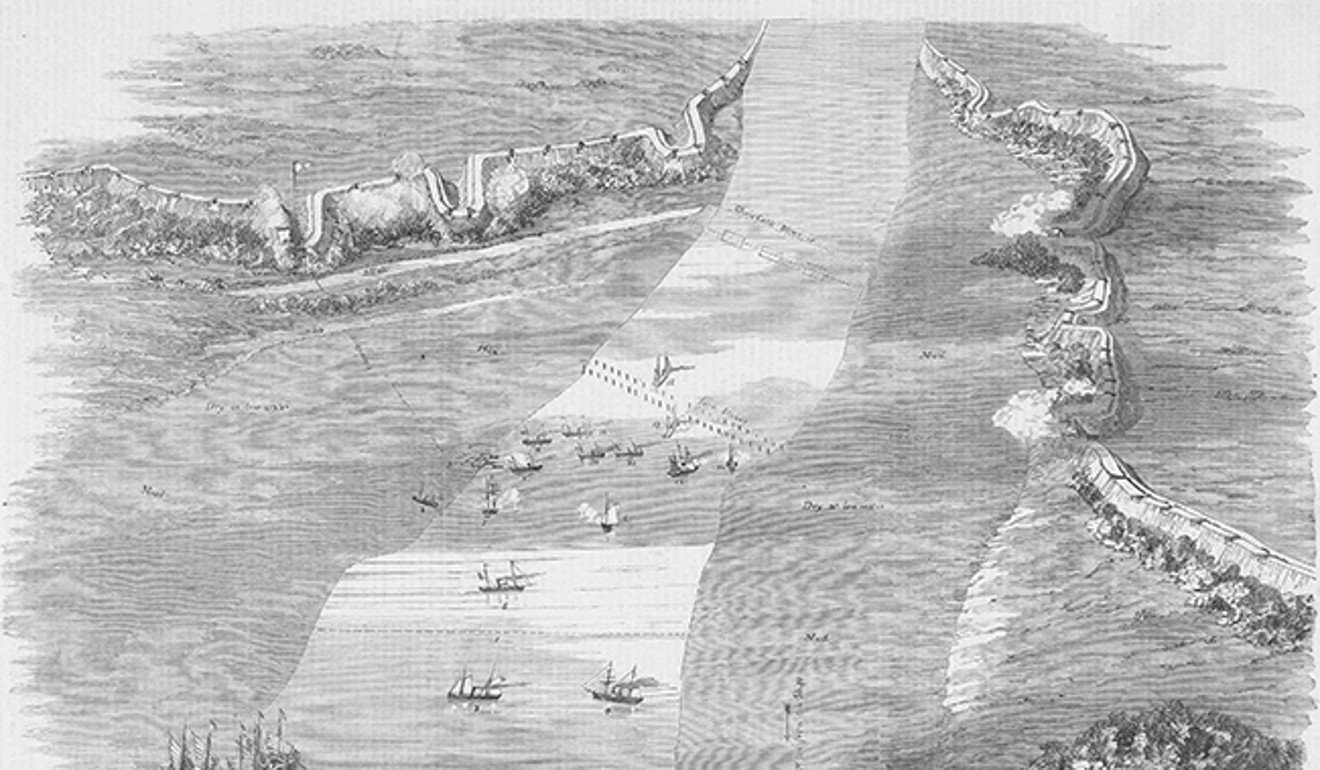

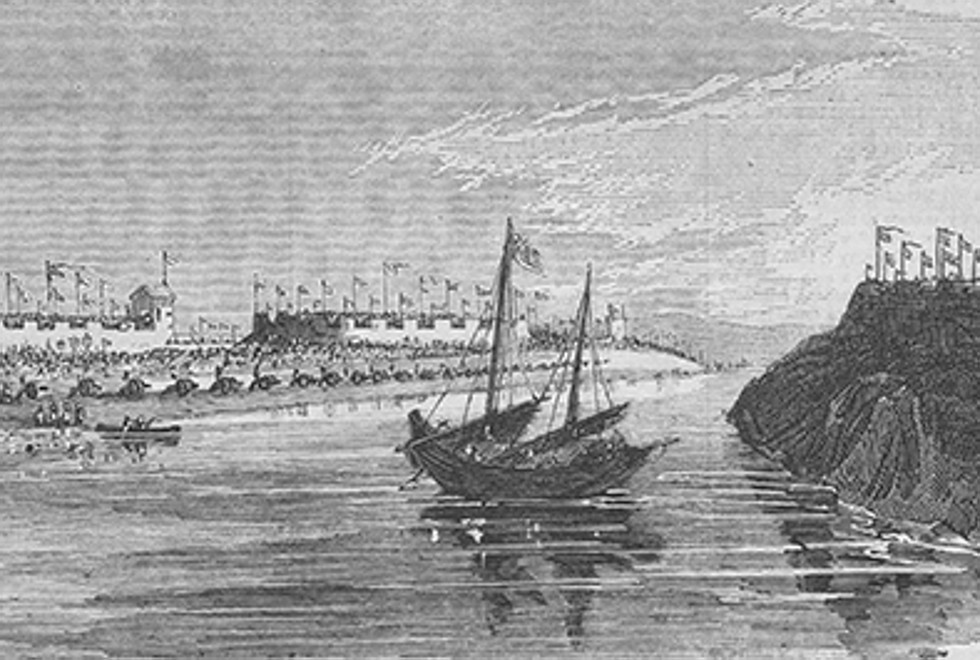

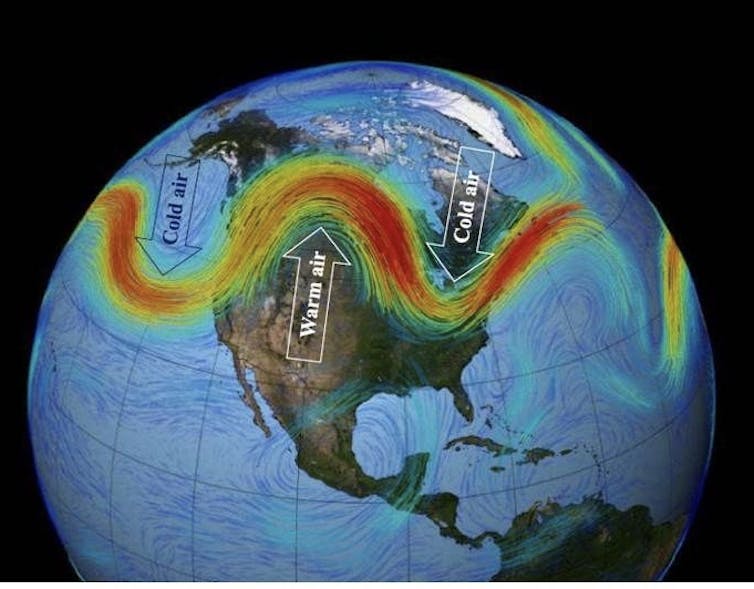

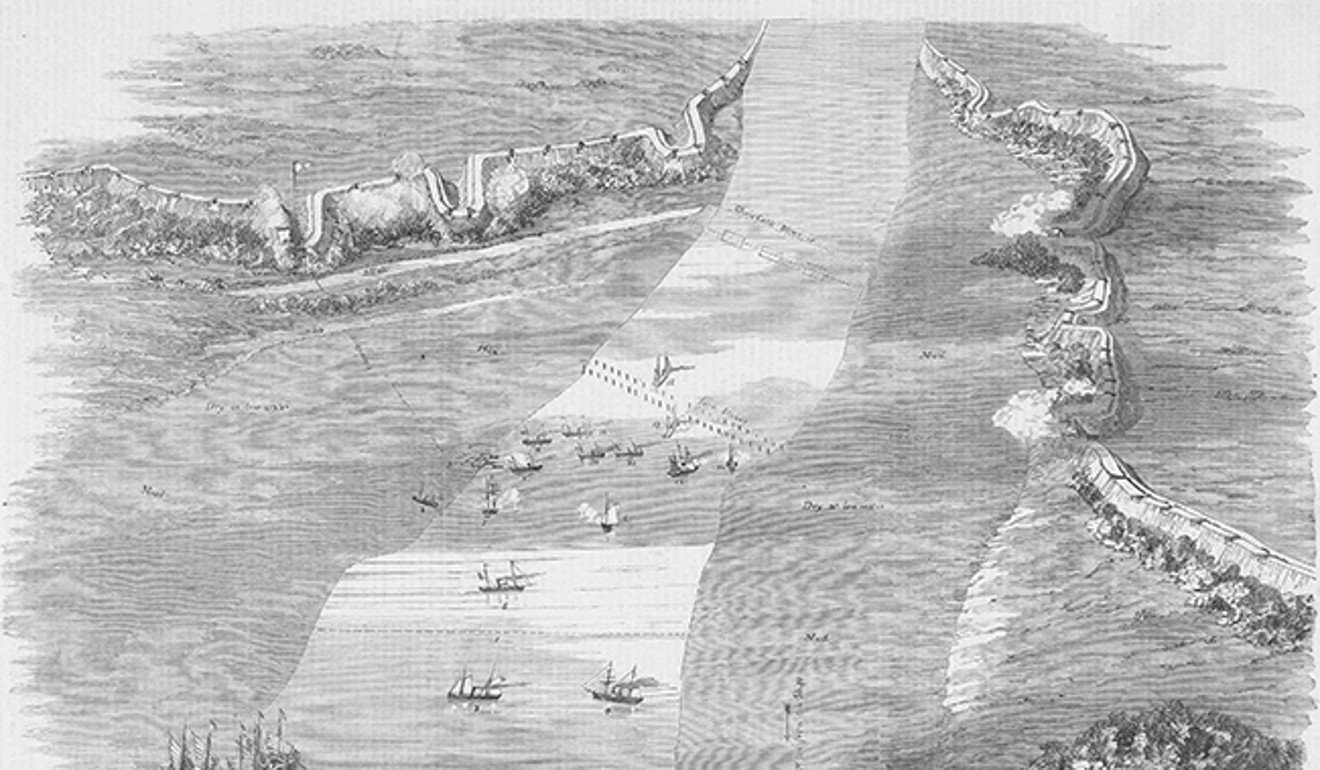

The Toey-Wan during the Second Battle of Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River on June 25, 1859, in a lithograph by T.G. Dutton. Picture: courtesy of George W. H. Cautherley

The second opium war, 1856-60. When in 1856, the 1844 US-China Treaty of Wangxia expired, American envoy to China William Reed set about negotiating new terms of trade, permission for diplomatic residence in Beijing and the extension of religious freedom to Christians.

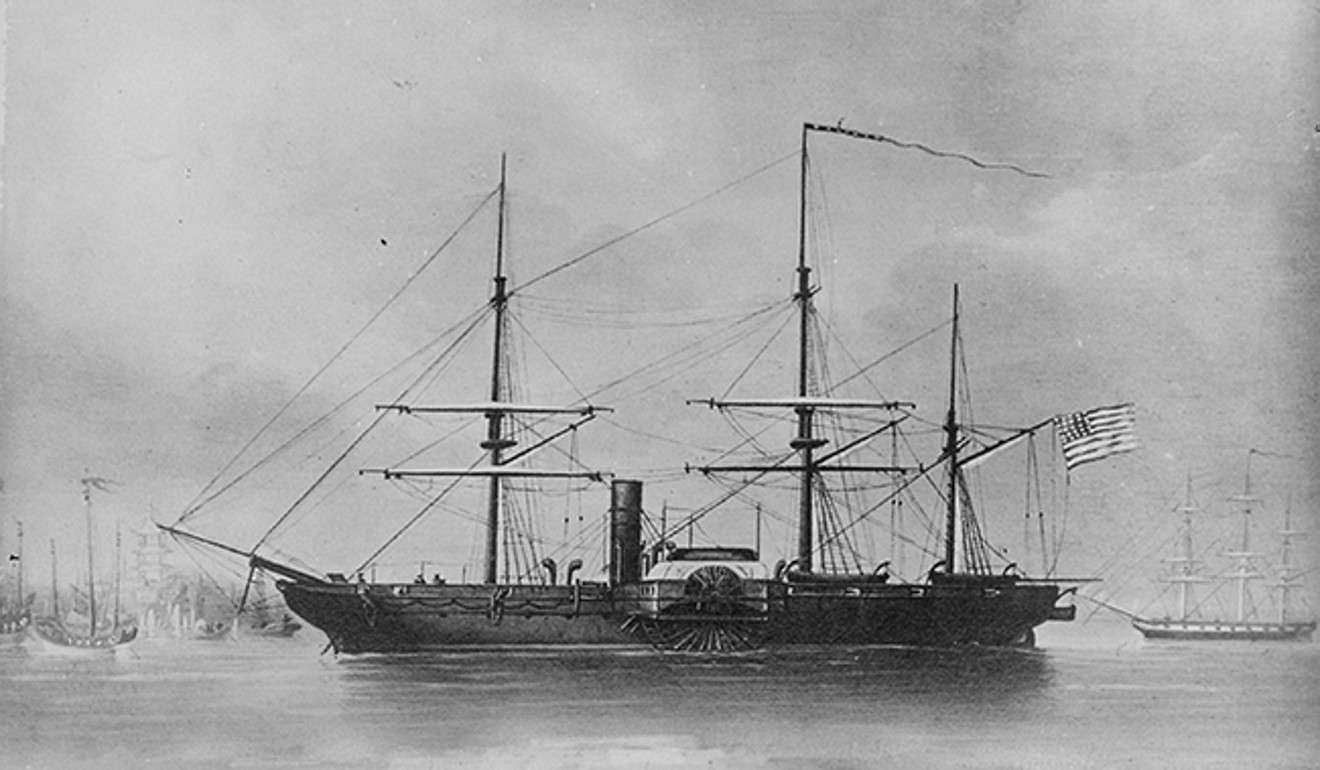

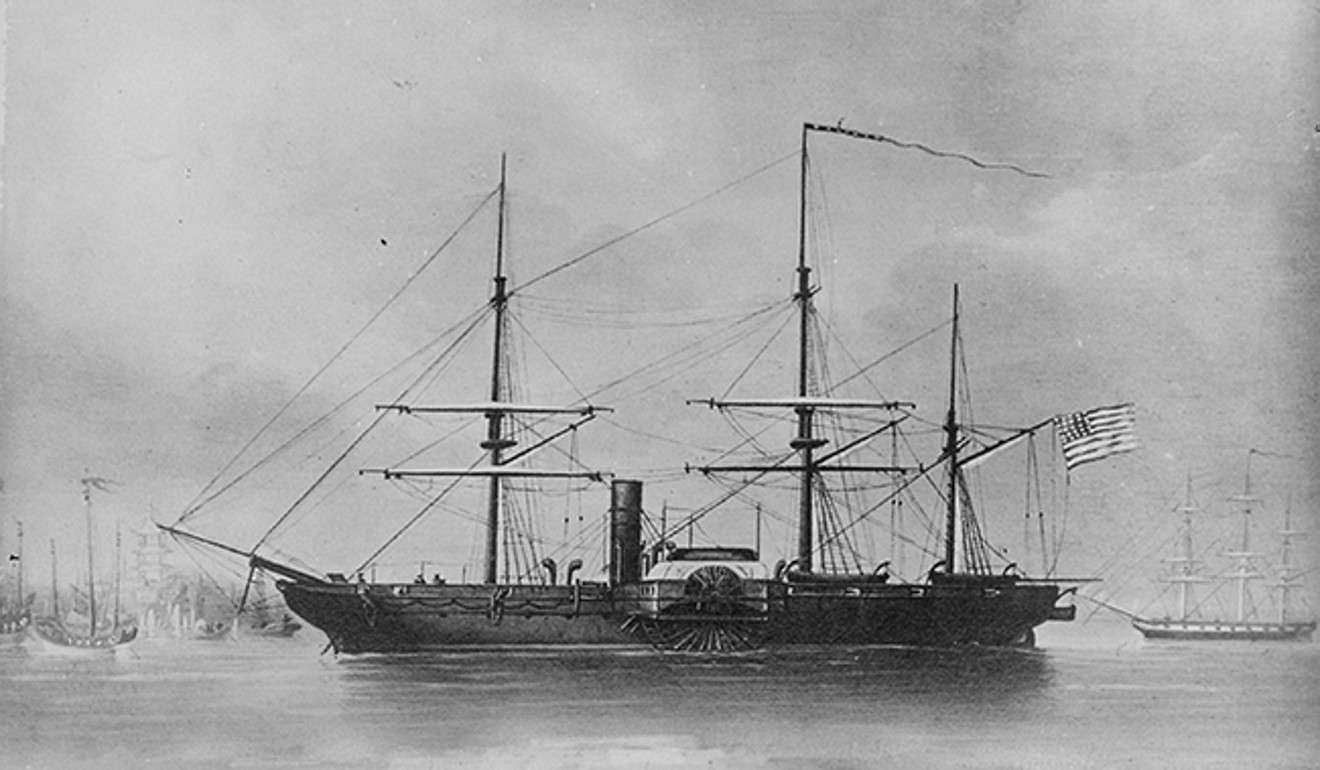

Following the eventual conclusion of these negotiations, in 1859, his successor, American minister John Ward, embarked in Hong Kong aboard the USS Powhatan destined for Beijing, accompanied by the hired steamer Toey-Wan, on a mission to ratify what had become known as the Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin).

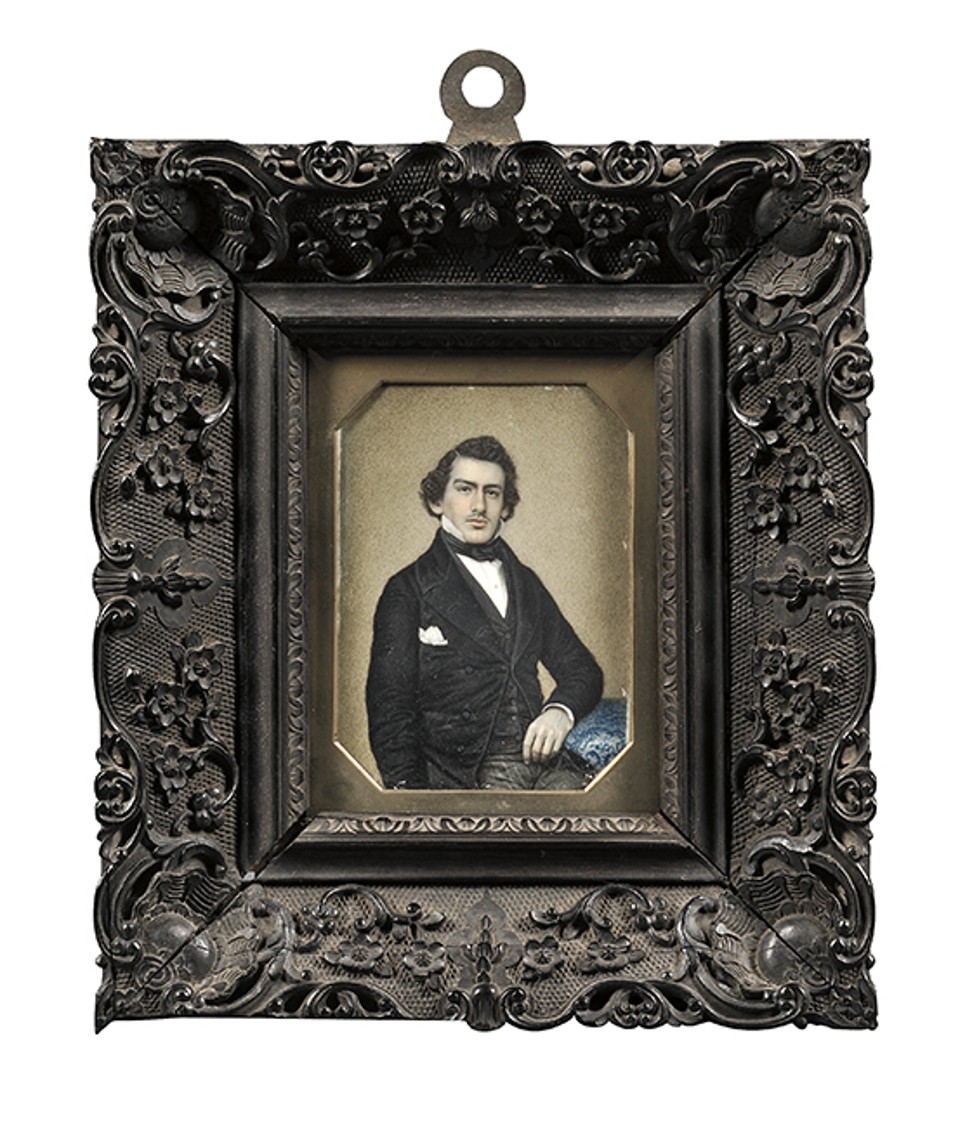

George Washington (Farley) Heard. Picture: courtesy of Skinner, Inc.

Among those he took with him was George Washington (Farley) Heard. Ward had met Heard, an American of about 22 years of age, en route to Hong Kong from America and, having taken a liking to the young man, asked him to join the American Legation as an attaché.

Heard had been travelling east to join his uncle’s firm, Augustine Heard and Company, one of the two largest American trading companies in China from the 1840s to the 1870s. He would later manage the company in Canton, and serve as the chairman of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in 1870.

At the same time as the American party was setting out from Hong Kong, an Anglo-French naval force began making its way north from Shanghai with newly appointed envoys for embassies in Beijing. But while the Americans – neutrals in the opium wars – were welcome, the British and French were less so.

When, towards the end of June 1859, the British began to remove barricades placed across the Peiho River by the Chinese to arrest their progress towards the capital, they came under attack. The second of three battles for the Taku Forts to take place during the second opium war ensued, an engagement that caused serious loss of British life and vessels, and which the Americans witnessed at close quarters.

Heard provided the following first-hand account of the battle in a journal he kept throughout his time with the legation, and now published by Proverse Hong Kong as Through American Eyes.

The USS Powhatan, circa 1859. Picture: courtesy of Gillian Bickley

USS “Powhatan” off Peiho

27 June 1859

On the 24th June, the “Toey-Wan” having on board Commodore Tattnall, Captain Pearson and a few of the officers of the ship – Mr Ward the Minister and Mr W[ard] his Secretary and the three interpreters, Mr Lurman and myself got under weigh at 8am to endeavour to communicate with the shore and send news of Mr W[ard]’s arrival and demand permission to proceed to Peking, there to ratify the Treaty of Tientsin [Tianjin].

Got over the bar and at 10am we were unfortunate enough, or as it turned out to be, fortunate enough to get hard aground on the mud at the entrance to the Peiho River which extends out at some distance from the shore and is bare at low water. We got on it at low high water and so we were high and dry at low tide.

When in this position the Admiral of the English sent a gunboat “Plover” 86 to our assistance with the exceedingly courteous offer – that if we couldn’t get off, to take the “86” and raise our flag on her and use her entirely as if she was an American ship. Before this, however, the tide had gone down so much it was found impossible to move her and Commodore Tattnall declined the amiable offer of the Admiral thinking he should be able to get off with the next flood.

At 2pm we sent on the barge with the Interpreters and Lieutenant Trenchard to find out whether there was anybody there of sufficient rank to communicate with.

The answer was negative. The party was received at the end of a jetty by about forty men, one of whom was spokesman. He said that there [are] very few men in the forts, no mandarin there even of the sixth rank (white button), that they had received orders from Peking not to allow any vessel to enter the river, and that they should be obliged to fire on anyone endeavouring to pass and break down the barriers.

We managed luckily to get off at about 8.30pm and we anchored outside the English ships, between the “Coromandel” and the junks which contained the English marines and their reserve forces of sailors and troops.

During the night, the first barrier was blown up by the English, who received a shot from the forts.

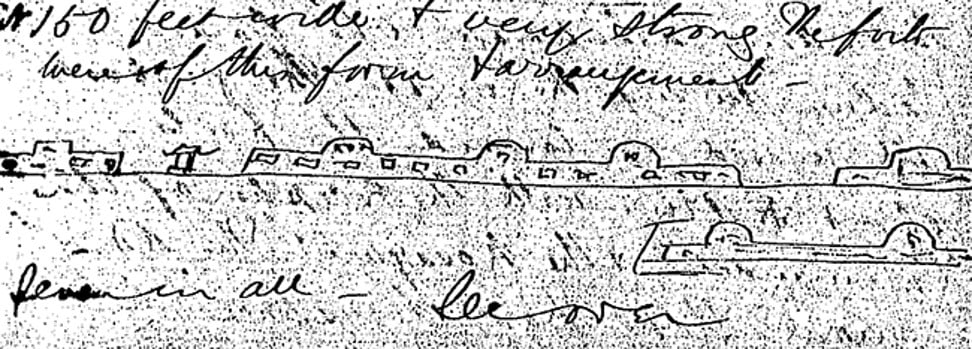

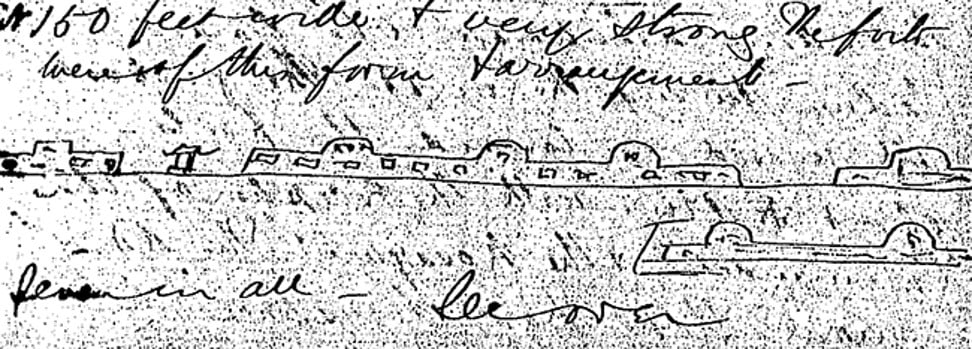

The barriers appeared to be three in number – the first: Iron stakes of this form connected with heavy chains, which was the one blown up by the English during the night of the 24th; the second barrier was of stakes; and the third, as I learned, was composed of heavy booms and logs chained securely together. Captain Wills swam up to it and found it a hundred and fifty foot wide and very strong. The forts were of this form and arrangement –

A sketch by George Washington (Farley) Heard, circa 1859.

Picture: Baker Library, Harvard Business School

– seven in all – see over

Another sketch by Heard to illustrate the formation of the

forts, circa 1859. Picture: Baker Library, Harvard Business School

At daylight the following morning the English began disposing of their forces. – Their ships outside the bar were:–

“Chesapeake” “Highflyer” “Magicienne”, “Fury”, “Assistance”, “Cruiser” and “Hesper”. The gunboats inside were:– “Kestrel” 69, “Janus” 76, “Plover” 86, “Banterer” 79, “Opossum” 94, “Forester” 87, “Lee” 82, “Starling” 93. In addition to these forces were the “Nimrod”, “Cormorant”, two large dispatch boats, and the “Coromandel” (the Admiral’s tender which was afterwards used as the Hospital ship).

The French had their gunboat with sixty-four men on board – the “Nosagari” in cooperation with the English forces.

The “Toey-Wan” remained at the same anchorage she had taken during the night. The gunboats all moved in towards the forts about 8am, with the exception of the “Coromandel” and the “Nosagari”. The Admiral Hope had transferred his flag to the “Plover” 86, and we saw him sitting amidships on a coil of rope going in ahead of everybody else. The gunboats soon got in near the forts, where some of them got aground and the rest anchored near them.

All the eight forts opened their fire at nearly the same time and they all seemed to direct their fire on the Admiral’s ship, which they distinguished by his square blue flag. The execution by the heavy guns of the forts was terrible

The “Coromandel” and “Nosagari” went in about noon and took up their position on the extreme left of the squadron, the “Nosagari” being inside of the “Coromandel”.

No movement was made till 2.30pm on either side, when the “Plover”, followed by the “Kestrel” and “Cormorant”, steamed up by the first barrier to the second and commenced pulling up the stakes. One had already been pulled out and the second one loosened when at 2.40pm the middle fort number three fired a heavy gun at the “Plover”. The fire was returned by the “Cormorant” and the cannonading became general throughout the forces on both sides. The forts discharged their guns almost as rapidly as the English and did great execution. All the eight forts opened their fire at nearly the same time and they all seemed to direct their fire on the Admiral’s ship, which they distinguished by his square blue flag.

The execution by the heavy guns of the forts was terrible. The men were twice swept away from their quarters on board the “Plover” and in less than an hour she only had three men left. The Admiral transferred his flag on board the “Opossum” 94 and she was terribly shot. Six men killed outright and many more severely wounded. He then went on board the “Cormorant”, where he remained till night. He himself was severely wounded in the beginning of the action but like a gallant fellow, as he is, refused to be carried below, but remained on deck among his men. The first shot fired from the forts took the head off the Captain of the “Plover” 86. [Rayson] his name was and a fine young sailor, as I ever saw. He came on board the “Toey-Wan” the day previous, when we were aground, to offer his assistance in the name of the Admiral.

Dark legacy of Britain’s opium wars still felt today amid fight against drug addiction and trafficking

We found we were just out of range of shot where we were at anchor and so we remained there. At about 4pm as we were sitting down to dinner, a young fellow from the Admiral’s ship, the “Plover”, at that time, came on board of the “Toey-Wan”, told us the state of the things, and asked us for the Admiral, to assist in towing up the reserve boats of the English. The tide and wind were both against them, and in rowing they would not have been able to reach the scene of battle for a great while. The boats were lying just astern of us and [we?] were hanging on to the junks.

Commodore Tattnall consulted with Mr Ward, and both concluded to do it, thinking it a course which met with their “unqualified approbation”. The Commodore then ordered us to the junks – I mean the US Legation to go to the junks – saying a steamer about to tow up the English boats into the middle of the fire was not the proper place for Mr Ward when the English and French Ministers were both aboard their respective vessels ten miles off.

As the order was peremptory we were obliged to obey and the barge pulled us on board.

They paddled up to the “Cormorant” on the debris of the boat and found the Admiral lying on the deck and heads, arms and legs lying round in every direction, and the decks streaming with blood

The “Toey-Wan” then towed up the boats of the English and anchored herself between the “Nosagari” and the “Coromandel”, both of whom were firing very rapidly. The “Toey-Wan” remained there three-quarters of an hour and while in that position the Commodore went to pay a visit to the Admiral to offer his sympathy to a wounded brother officer, who was severely wounded and who was suffering a mortifying defeat. He pulled up in the middle of one of the hottest fires that ever came from the forts, and when nearly alongside of the “Cormorant”, the ship on which the Admiral was at the time, a shot struck his boat, knocking the stern sheets out of it, throwing the Commodore and Lieutenant Trenchard out of their seats and killing the coxswain. They paddled up to the “Cormorant” on the debris of the boat and found the Admiral lying on the deck and heads, arms and legs lying round in every direction, and the decks streaming with blood.

While the Commodore was on board, a lieutenant was brought up dead and laid on deck and two men were struck down at a gun. An English boat came alongside at this time and the officer in charge offered to take the Commodore and his barge’s crew back to the “Toey-Wan”. Three of the barge’s crew could not be found in the excitement: they came back to the “Toey-Wan” in the middle of the night, and when asked where they had been they replied that –

“They found themselves in the way and they thought their only way to get out of the way was to go to the guns”.

The Toey-Wan during the Second Battle of Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River on June 25, 1859, in a lithograph by T.G. Dutton. Picture: courtesy of George W. H. Cautherley

By this time the fire from the forts had slackened considerably and the English determined to bring out all their boats, land a storming party, and endeavour to carry them. For this purpose two gunboats, the “Opossum” and another came out of the fire as did the “Toey-Wan” for the rest of the boats.

Mr Ward determined to remain no longer on the junk but get back to the “Toey-Wan” and go in to danger with her, and of course we (i.e. young Ward, Lurman and me) determined to go too. Mr Ward went to the “Toey-Wan” in the boat of Captain Wills of the “Chesapeake”. The Interpreters remained on the junks. Young W[ard], Lurman and myself all got on the “Opossum” at first, but afterwards went to the “Toey-Wan” in a boat sent for us.

We had about a hundred marines on board the “Toey-Wan”.

As we approached the forts, the firing did not seem to increase, and nearly everybody seemed to think an easy victory would be gained by the stormers.

The boats all collected within the lee of the ships and giving three cheers pulled in to land.

Then it seemed as if a flame burst out all over the eight forts, so rapid was the fire, and such execution it made. We could see the shot strike in and around the boats in every direction, and every shot took effect. Whole rows of poor fellows were mowed down at a time. One boat was cut in two by a shot and many men killed in her and the rest were picked up by the other boats.

The “Nimrod” and the gunboats were firing shot and shell, and rockets to protect the stormers and cover their landing. The red sun was just going down behind the middle fort, as they landed, and it was a wild-looking sight. The whistling of the small balls, the fierce roar of the heavy ones, and the bursting of the shell and rockets made the little “Toey-Wan” tremble all over. A great many shots struck all about the “Toey” but not one hit the boat itself. One shot passed between the awning and the deck between Mr Ward and myself and fell into the water within ten or thirteen feet of her counter and a great many fell between us and the Frenchman, who was anchored on our right.

Then it seemed as if a flame burst out all over the eight forts, so rapid was the fire, and such execution it made [...] One boat was cut in two by a shot and many men killed in her

As we found afterwards the boats of the storming party could not approach near the shore as the water was so shallow, and as soon as the boats touched, a good many of the men jumped out and sank in up [to] their necks in the mud and water, in which position several were drowned before they could extricate themselves. Those who got to the shore wet their powder so none of them could return a shot and the fire from the forts was so fatal that a great many were killed. It is estimated that a hundred men were lost during the landing alone.

When they got to the shore, they found there was a deep ditch, through which they had to wade, waist deep – then a little hard mud, then another ditch filled with mud and water, that could only be passed in swimming, and then there was a third ditch filled with mud and water, and sharp iron spikes and lances. Very few of the men got up to the walls of the forts, which were about twenty-five foot high, and swarming with men, who fired at them with rifles, gingalls [a type of gun], and arrows, which were very long and barbed in such a manner that when the arrow entered the flesh, the head detached itself and remained in the wound.

The few men who succeeded in getting to the walls tried to scale them with ladders but the ladders broke and they found there was no safety but in flight. Captains Commerell of the “Nimrod” and Heath of the “Assistance” told me that when they were at the foot of the walls they had to lie close in under them, and as soon as a head was seen, the Chinese sent a bullet through it – that the Chinese were armed with real Minie Rifles, [and] were large men wearing fur caps. Captain Commerell, who was in the Crimea, says he repeatedly heard the Russian word for “powder” cried within the walls, and a good many of the marines who were in the same position heard the same word used. Several men declare they heard in good English, “Why in the devil don’t you pass that powder up?”

From opium wars to HSBC, writer Maurice Collis brought Asia to vivid life

Whether this latter was the effect of their imagination or not I don’t know, but I am inclined to believe what Captain Commerell says. I think there were other men than Chinamen inside the walls probably some runaway sailors or mercenary Russians. They understood the science of gunnery too well not to have been trained to their guns, and they stood to them well. The Chinese burnt blue lights etc. as soon as it was dark and shot down the men by their lights.

They began to come off from the shore about 10pm and kept coming off all night. Several boats came to the “Toey-Wan”, where the crews were supplied with food and shelter; other boats made fast to her stern and lay there all night.

The “Nimrod” and the “Coromandel” anchored close by us during the night. The firing from the forts continued at intervals all night, and during the day. In the morning we did all we could to assist the English, in getting their wounded off etc., etc. We could see in the morning the Chinese walking about on the beach in front of the forts cutting off the heads of the dead and wounded; others were picking up the swords, guns and pistols etc. that were lying about on the beach.

We came out to ships about 11am, towing out two large launches filled with wounded and bringing out the first news of the battle to the English and French Ministers.

Hart the Commodore’s Coxswain was buried in the evening: and it was a solemn one after the scenes we had passed through.

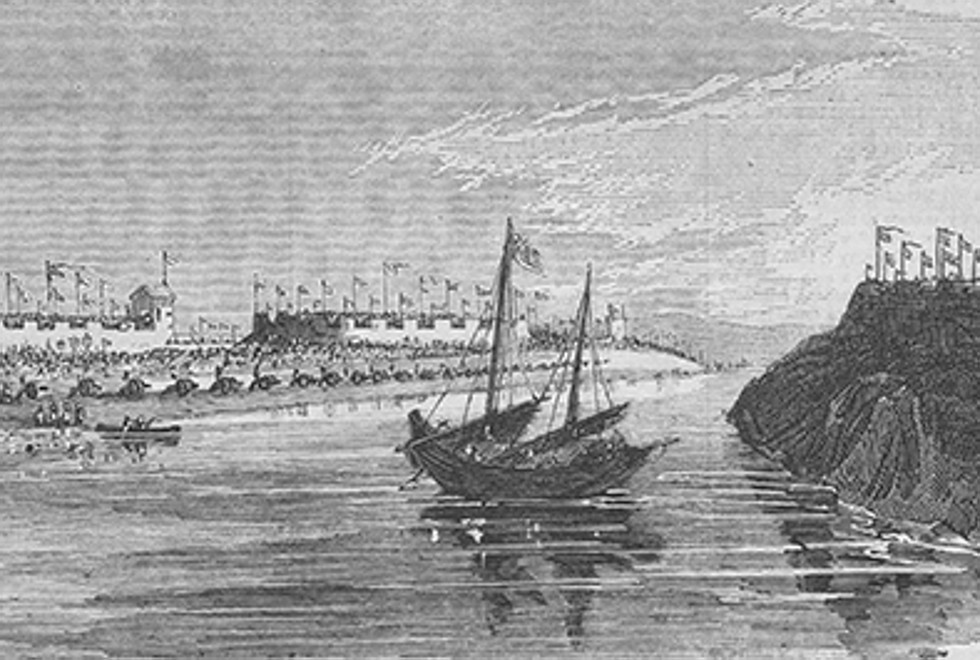

An engraving of the attack by Anglo-French forces on the Chinese fortifications at the mouth of the Peiho River, on June 24 and 25, 1859. Picture: courtesy of George W. H. Cautherley

USS “Powhatan” off Peiho River 29 June 1859

The Chinese had told us, when we sent our boat on shore [on] the 24th, that the real Peiho River was ten miles farther North. The Commodore determined to send the “Toey-Wan” up there to see if there was a river and endeavour to communicate with the authorities, and leave a letter from Mr Ward to the Governor General of this Province to announce his arrival “dans ces parages” [in this area].

I got leave to accompany the party which consisted of Messrs W.W. Ward, Martin, Aitchison, and Dr Williams and Lieutenant Habersham. It was sort of a Men of Wars cruise “there and back again”.

We left the “Powhatan” at 10.30am and got under weigh at 11.30. It was a beautiful day though rather windy and rough. Our course was North about five knots an hour and we carried on this course five fathoms of water as far as six miles from the “Powhatan”. The flood tides in this part of the Gulf of Pechelee sets to the North outside the bar. [The] Wind was North North West.

A good many large junks were seen about four miles North of the forts at the mouth of the Peiho, and large piles of salt dotted the shore in every direction. The shore was very low and there seemed to be a dike along the shore as we could see in almost every part of it junk masts above the land.

When our party told the Chinese they were from the United States of America, the Chinese asked them where it was, saying they had never heard of that country

The water shoaled very gradually, but as we stood into toward land we got to ten foot water where we anchored to take bearings etc. We were about three to four miles from shore, and could distinctly see a large entrance, the mouth of it crowded with junks’ masts, of which there was a whole forest. In the middle of the entrance there were two islands apparently, one of which was very thickly covered with houses and the other entirely covered by an immense square fort, made of the same material as those at the mouth of the Peiho – mud – junks’ masts all round, hulls down out of sight. –

On the left bank of the entrance as you approach it from the sea, was a large round fort with long wings extending away back out of sight, and seemingly connecting with another square fort also on the left bank. It looked like a very strongly fortified place and a place too of much importance if one may judge from the great number of junks, in and around the entrance. Behind the fort was a very large village containing several Joss houses whose peaked roofs stand above the surrounding houses. There were a number of tall trees resembling poplars near the village.

Country looked fertile and populous – vast number of junks. We were near enough the forts to see men at work on the tops of the bastions with our glasses (binoculars or telescope).

After getting bearings of the forts etc. we stood to the Northward, and found ourselves in a bight of the coast, and at the water’s edge were a number of villages. I counted six of them in sight and near us at the same time. [The] country looked fertile and apparently swarming with population. We anchored in two fathoms about two and a half miles from one of them and sent an armed boat in, with Messrs Merchant, midshipman, Martin, Interpreter, and Ward, Secretary of Legation.

Coin stash that puts new spin on China’s 100 years of humiliation

As they approached the shore the Chinese streamed out of the village; men, women and children running as fast as they could go. Three junks were anchored near shore, and as the boat got near them, their crews jumped out and waded and swam ashore.

The boat soon grounded and as the gentlemen in it couldn’t get the boat in further, got into the water to wade ashore. The crew remained in the boat. As the three got near the shore three-quarters of a mile from their boat, two carriages drawn by four horses each started off full gallop, from the village – and everyone was in full flight. However, two or three men remained and came down to meet the party. They were very large men, two of them almost giants – there were soon about twenty collected round their party and the interpreter found no one of them could read (having different dialects, characters were often used to communicate).

Another man came down from the village who was one of the local authorities. He received the letter for the Governor General and then told the party that [there] were four thousand troops encamped in the vicinity and that a courier had gone off to call for their cavalry and advised them to run for their boat as fast as possible, saying that the villagers were all well disposed enough towards foreigners, but the soldiers were Tartars who recognized no distinction between foreign barbarians. The Chinese all called out to them to run fast – and so they did. Before they could get to their boat the shore seemed alive with cavalry two of whom chased our party in the water till they got up [to] their waists. They got to the boat safely but very much fatigued and pulled back to the “Toey-Wan”.

Two or three men remained and came down to meet the party. They were very large men, two of them almost giants – there were soon about twenty collected round their party and the interpreter found no one of them could read

When our party told the Chinese they were from the United States of America, the Chinese asked them where it was, saying they had never heard of that country.

This part of the country seemed very fertile indeed and there was a great number of inhabitants. A good many junks were seen standing to the Northward, and I saw one under full sail just behind the beach where our party went ashore. We could also [see] many masts over the land. There were not many trees to be seen, but a number of shrubs and bushes.

Returned to the “Powhatan” at 8.30pm.

An engraving of the attack by Anglo-French forces on the

Chinese fortifications at the mouth of the Peiho River, on

June 24 and 25, 1859.

Picture: courtesy of George W. H. Cautherley

USS “Powhatan” Off Peiho River 4 July 1859

The “Glorious Fourth” – as they call it, and no doubt every village, town and city in the United States is ringing and shaking from bells, crackers, guns and cannon today. We are celebrating the day in a quiet manner enough. The American Ensign waves from each mast head, and the spanker gaff, and at noon we fired a salute of twenty-one big guns. This, together with a bottle of champagne at dinner, comprised our celebrations. All the English and French ships at the anchorage hoisted the American flag at the main mast head out of compliment to us and kept it there all day.

The English have been employed all the week in getting their gunboats off and in taking care of their wounded etc., etc. They had six boats ashore and sunk on Sunday morning the 26th. The “Lee” 82, “Plover” 86, “Starling” 93, “Kestrel” 69, “Haughty” 89, and the “Cormorant”.

They have succeeded in saving all but the “Lee”, “Plover” and “Cormorant” which they have destroyed. The forts have been firing on them all the week, and I understand have killed several more men.

The English estimate their loss at 452 – 87 killed, wounded 363 and missing [sic].

On the 2nd July the Chinese sent a junk with a letter from the Taoutai of the village, to announce that the letter given by our party to the men on the beach had been forwarded to the Governor General at Tientsin. The Taoutai sent another junk containing twenty sheep, twenty pigs, sixty ducks and chickens and 2,500 lbs of rice and flour and a great quantity of fruit etc.

The “Glorious Fourth” – as they call it, and no doubt every village, town and city in the United States is ringing and shaking from bells, crackers, guns and cannon today. We are celebrating the day in a quiet manner enough

USS “Powhatan” off Peiho River 7 July 1859

On the 5th July, two white button mandarins (sixth order) came off to the ship with an answer to Mr Ward’s letter, written by the Governor General – and inviting Mr Ward to an interview. Mr Ward has appointed tomorrow as the day and we are going on board the “Toey-Wan” this evening to stand in and so go in tomorrow morning.

The mandarins were shown all over the ship and they were apparently much pleased and astonished at the guns and machinery.

I went on board the “Chesapeake” last night with Lurman, Habersham and Semmes to make a visit and aid young Wish. –

“Fury” sailed on Monday 4th, “Du Chayla” and her tender, and “Assistance” on Tuesday 5th, “Magicienne” [on] Wednesday 6th. Mr Bruce and Rumbold came on board on Monday to see Mr Ward.

10.30pm

I went on board the “Toey-Wan” this afternoon at three with Messrs Wards, Martin, Lurman and Commodore Tattnall and Lieutenants Habersham and Trenchard. Got under weigh at 3.20pm, the “Powhatan” having got up her anchor, and following us into an anchorage nearer shore. Found a good anchorage for her in twenty-seven feet [of] water, and then we stood in towards land. Saw the forts and we anchored in two fathoms [of] water. Several junks were in sight two and a half miles from us, and we sent the boat to them. I went in her with some others. Rough water and we sailed very fast. Heard on board the first junk [that] there were several mandarins on board another one further in.

Went on board of her and found a blue button, crystal and white button mandarin on board with a numerous retinue. We went in the dirty little cabin where they spread several cushions etc. for us to sit on and they squatted down too. Passed round some delicious tea and some very nice little sponge cakes, which were very palatable as we were rather hungry. Then there was another kind of cake made of beans – it looked like brick dust and tasted very much like it too. One of them had a very small bottle filled with some kind of white snuff which he passed over to me. I tried it and found it rather agreeable – it was a powder that might have been composed of camphor and musk. The blue button mandarin had on a tunic, or whatever they call it, of blue navy cloth, very fine texture, and Mr Martin said it was Russian cloth, and that he [Martin] had bought it at Ningpo and cheaper than he could have done in America or Europe.

These Mandarins were as hospitable as possible and all smiles etc. – no allusion was made on either side to the battle of the 25th June

They called the American flag, the “flowery flag”, and said they should know us very well. They are going to send us a boat tomorrow, and they have buoyed the whole channel [plotting a safe path]. I have got a line of soundings from the anchorage of the “Toey-Wan” to the junks. They tell us there is 30 foot of water in shore under the batteries and that there is water communication from this place up to Tientsin. I don’t know the name of the place – but it’s the same place so strongly fortified we saw on the 29th June. We go in tomorrow in full uniform to an interview with the Governor General. The Mandarins told us we must be particularly careful not to go anywhere, where the guides do not take us, as the city is all a mass of ambuscades for the English.

These Mandarins were as hospitable as possible and all smiles etc. – no allusion was made on either side to the battle of the 25th June. Tomorrow I shall have something to write about, I think, but there’s nothing now.

Text © P.roverse Hong Kong 2017.

Through American Eyes, edited by Gillian Bickley and transcribed by Chris Duggan is published by Proverse Hong Kong