Indigenous rights, Mother Nature, decolonization and the environment have been at the heart of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s songwriting since she was in her early 20s. Sixty years later, these issues are more relevant than ever—just like Sainte-Marie herself

Andrea Warner

(Photo, Matt Barnes. Beadwork, Katie Longboat. Beadwork photography,

Buffy Sainte-Marie doesn’t think in milestones. She turned 80 in February, but the Cree artist feels pretty much the same as she always has.

“I wasn’t that different when I was 17 or 52,” Sainte-Marie says with a laugh, over the phone from her home in Hawaii. “It’s all the same.”

She is joking a little, but her statement is close to the truth. The iconic singer-songwriter has had 30 lifetimes’ worth of accomplishments since the release of her debut album, 1964’s It’s My Way!, and she doesn’t intend to slow down any time soon. “I think a lot of people have the idea that the playground closes at a certain time in their life,” Sainte-Marie says. “And as an artist, as a thinker, as a learner—nah, the playground does not close for me. It’s open weekends and 24-7 and I’m really a glutton for experience and information.

This is the open secret, at least in part, to her own feeling of eternal youth: Buffy Sainte-Marie is always a work-in-progress. In addition to writing and playing music, she has made a name for herself as an activist, an educator, a mixed media digital artist, a children’s book author and even a Sesame Street supporting player (she played herself on the TV classic for five years). She is insatiably curious and eager to innovate. Done is dead, and she’s too busy learning, creating and doing to spend time in a finite state. “It’s really a terrible disservice put upon youth to try and talk them into ending [their playful curiosity],” Sainte-Marie sighs. “They should stay like that forever! I’m having just as much fun at 80. I still ride horses and jump over fences; I’m still gonna run up and down stairs; I still dance and I still make music. I do exactly the same things, and many of them much better now than I did 10 years, 20 years, 40 years earlier. You can keep getting better in every way, including physically, and you can get smarter forever.”

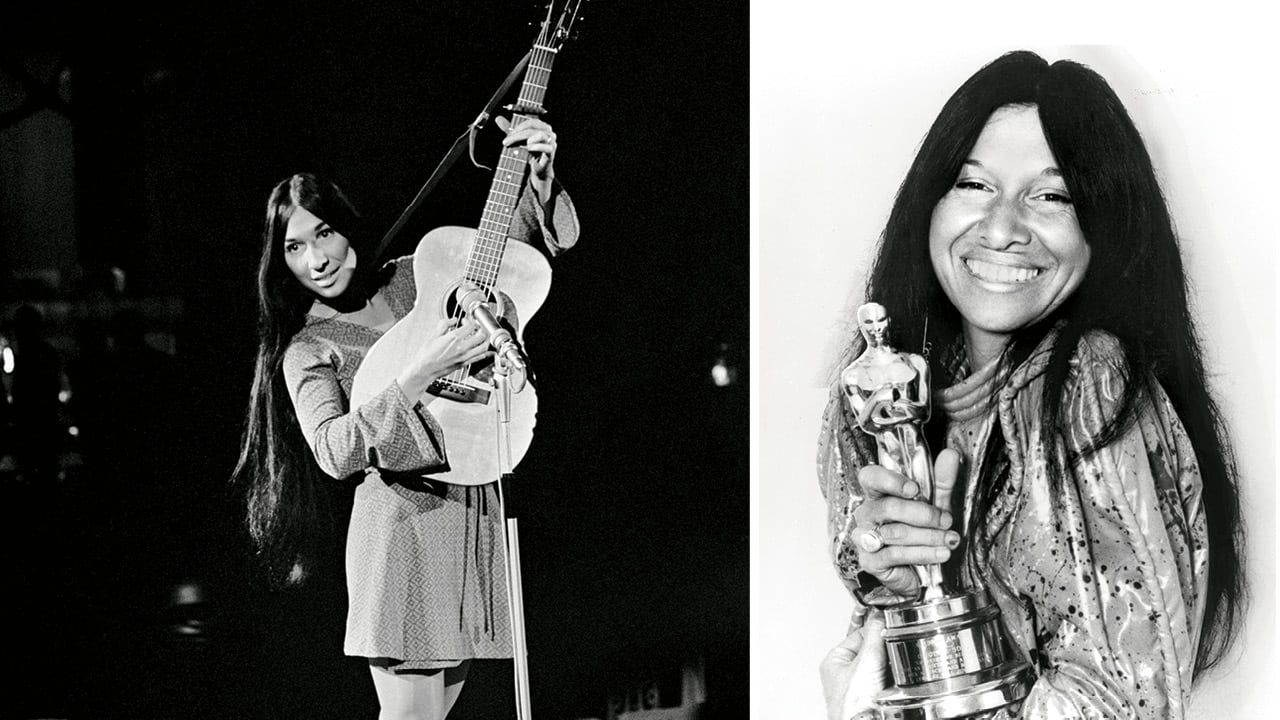

Left: Sainte-Marie performing at a Dutch gala in 1968. Other performers that year included Nancy Sinatra and Joan Baez. Right: Sainte-Marie became the first Indigenous person to win an Academy Award in 1983, for co-writing “Up Where We Belong” for An Officer and a Gentleman (Photos: Jac De Nus; Getty)

Sainte-Marie is well aware that some people see her as frozen in time in the 1960s, rubbing shoulders and even occasionally sharing stages and songs with casual friends and fellow famous musicians, like Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. But that misses the bigger picture.

She has always been a radical musician. Aside from making what is widely considered to be one of the first electronic albums, 1969’s Illuminations, she was also one of the first people to use an electronic powwow sample in a song, in 1976’s “Starwalker.” Her 1992 album, Coincidence and Likely Stories, was the first to be delivered over the internet (Sainte-Marie recorded it in Hawaii, then sent it to her producer in London). In addition to winning six Junos and being inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, Sainte-Marie is the first-ever Indigenous artist to take home an Academy Award (she co-wrote “Up Where We Belong” from 1982’s An Officer and a Gentleman). In 2015, she won the prestigious Polaris Prize for Power in the Blood—an electrifying album complete with club bangers and contemporary electronic powwow anthems.

Yet for all of her innovation, there’s also a timelessness to Sainte-Marie’s music. She writes about everything from love and heartbreak and Indigenous joy to peace and political corruption and environmental exploitation. Many of her songs are nuanced illustrations of how these themes not only intersect but also inform one another in ways both big and small. In 2020, It’s My Way! won the Slaight Family Polaris Heritage Prize designation, which is awarded to albums that have remained culturally relevant decades after their release

It is believed that Buffy Sainte-Marie was born in 1941 on the Piapot First Nation reserve in Saskatchewan, and taken from her biological parents when she was two or three. She was adopted by a visibly white couple in Massachusetts, though her adoptive mother, Winifred, self-identified as part Mi’kmaq. Sainte-Marie’s experience of being adopted out of her culture and placed in a non-Indigenous family by child welfare services is an all-too-familiar story in Canada. This practice was later dubbed the Sixties Scoop, referring to the decade in which it was most prevalent (though it had gone on well before the 1960s, and would go on for decades to come).

Sainte-Marie’s childhood wasn’t easy—she secretly suffered abuse inside and outside the home—but she says she was also able to cultivate a lot of happiness for herself. She was always close to Winifred, and credits her for nurturing and encouraging a lifelong love of learning. She also took comfort in solitude and, even as a little kid, always felt a strong connection to her inner creativity. Sainte-Marie surrounded herself with nature and animals and her own sense of wonder. She began playing piano when she was three, but school band and choir weren’t of any interest to her. The structured learning of traditional music classes were antithetical to Sainte-Marie’s natural gifts. She taught herself guitar but it wasn’t until she got to college that she began playing her songs publicly.

As Sainte-Marie developed as a songwriter and performed in Canada and the U.S., she also continued to research and reconnect with her Indigenous roots, meeting other young Indigenous scholars and activists on both sides of the border. She’d been told she was adopted from an Indigenous family in Saskatoon but didn’t know much else. After spending time at Toronto’s Friendship Centre (now the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto), two of her new friends suggested that Sainte-Marie was possibly the daughter of Emile Piapot, of the Piapot First Nation in Saskatchewan’s Qu’Appelle Valley. (The connection was made after discovering that Piapot’s own story aligned with what Sainte-Marie had pieced together about her origins.) Sainte-Marie met Piapot at a powwow in Ontario, and a short while later visited the Piapot reserve for the first time. In the early 1960s, she was officially adopted back into the Piapot family and given the Cree name Medicine Bird Singing.

Sainte-Marie performing at the 2015 Polaris Prize Gala. (Photo: Dustin Rabin)

In 1964, Sainte-Marie stepped into the biggest spotlight of her young life with the release of It’s My Way! She had already established herself as an important voice in the coffeehouse scene, writing the anti-war protest anthem “Universal Soldier” in 1962 and performing it several years before America even admitted they had soldiers on the ground in Vietnam. She opened her first album with “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” singing, “Oh it’s all in the past you can say / But it’s still going on here today / The governments now want the Lakota land / That of the Inuit and the Cheyenne.” The song thrummed throughout the ’60s and ’70s as Indigenous activists across Turtle Island (the name used for North America by some Indigenous people) organized grassroots efforts to demand Indigenous rights and land rights—and it continues to echo today wherever land defenders are on the ground, including Idle No More, Standing Rock and the Keystone pipeline protest.

Sainte-Marie suspects it was, in part, her Indigenous rights and environmental activism that led to her music being temporarily suppressed by many U.S. radio stations: “The administrations of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon didn’t want me opening my mouth about the environment,” she said in a 2019 interview with the McGill Daily. “They especially did not want Indigenous people interfering with their complete control of available land and natural resources.”

The suppression didn’t work, at least in the long run. Sainte-Marie has never stopped writing songs that demonstrate how colonization, Indigenous rights and environmental destruction are implicitly linked. Two standout examples are 1992’s “The Priests of the Golden Bull” and 2009’s “No No Keshagesh.” In just one verse of the former, she directly ties together colonization, greed and hypocrisy, the genocide of Indigenous people and environmental destruction: “It’s delicate confronting these priests of the golden bull / They preach from the pulpit of the bottom line / Their minds rustle with million dollar bills / You say Silver burns a hole in your pocket and Gold burns a hole in your soul / Well, Uranium burns a hole in forever / It just gets out of control.” In “No No Keshagesh,” Sainte-Marie uses humour to deliver a series of stinging truths about greed, capitalism and the environment, singing lines like “Got Mother Nature on a luncheon plate / They carve her up and call it real estate.”

Sainte-Marie in Vancouver in 2018, part of a photo series taken by Sacred MMIWG for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (Photo: Nadya Kwandibens, Red Works Photography)

Residential schools—and the subsequent Truth and Reconciliation Commission—are also never far from Sainte-Marie’s mind. In 1966, she released “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying,” a six-minute-long living history lesson that covers—among other topics, including colonization and genocide—the devastation of residential schools. (For context, this was 30 years before Canada’s last residential school closed in 1996.) When we spoke for this piece, she had just started reading Tamara Starblanket’s 2018 book, Suffer the Little Children: Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State. “She’s brilliant,” Sainte-Marie says of Starblanket, a Cree writer and educator who hails from Ahtahkakoop First Nation in Treaty Six. “There’s all kinds of opinions out there on the internet, and some people will say ‘Truth and reconciliation is dead.’ But truth and reconciliation is just step one and two, and it’s up to us to take steps three, four, five, six and forever.”

Sainte-Marie usually abides by one guiding principle: Stay calm and decolonize. But sometimes it’s easier said than done. “Right now I feel quite frustrated!” she says. “Since we just mentioned Tamara Starblanket’s book, you know, she’s the last surviving member of three generations of residential school torturees. They killed them all. Her parents, her grandparents, her brothers and sisters, they were all survivors of terrible things.”

These hundreds of years of colonization and violence stem from one source, and Sainte-Marie has spent years trying to bring more awareness to it: the Doctrine of Discovery. The doctrine was established in the 15th century and essentially granted Christian explorers the religious—and, therefore, ethical—justification to colonize and enslave non-Christian people and lands around the world. Sainte-Marie sees a clear relationship between the doctrine and the genocide inflicted by residential schools, and she would like to see it referenced prominently at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. (Indigenous nations and non-Catholic churches have asked the Vatican to rescind the doctrine, while the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called for Canada to repudiate it.) Sainte-Marie also wants the electric chair from St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, which was open in Fort Albany First Nation, near James Bay, from 1902 to 1976, on display as soon as visitors enter the museum. The chair was “homemade” and used to shock children, according to former students.

“The information itself is hard to stomach when I’m reading it myself, but it’s even harder to stomach to know that the impact of this difficult historical information is still in play today,” Sainte-Marie says. “Sometimes I’m such a jolly little Sesame Street entertainer. And then the other side of me is dealing with [this]. My own family and my own friends who have, all of their lives, experienced the poverty, the racism, just the pain of being Indigenous in a Canadian city, it’s just—it’s very hard and it’s frustrating.”

Without structural changes at society’s foundations, the colonial system is built to fail. Again and again and again.

“It seems like when you have a long life, things just keep looping around,” Sainte-Marie says. “We’re living in Machiavellian days, although most of the population never read The Prince.” She laughs. “That’s a blueprint for this current assholery. Historians will show you: Stalin and Hitler and, you know, just name ’em all. So, I guess, when you talk about songs lasting, if you’re the kind of person who notices classic human themes, then I guess that’s the kind of songwriter you are, too. It’s like examining trash. We’re doing colonoscopies on the human race!”

Singing truth to corrupt systems is one of Sainte-Marie’s superpowers, but she also wants to move the conversation forward and put her songs to work; particularly some of those “medicine songs,” like “Carry It On,” a soaring anthem about climate justice and taking care of our hearts. She invites the listener to step into hope, empowering us to collective action. But she’s not looking to get more famous, or even get more credit (though she absolutely belongs in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame). She just wants her songs to do their jobs, whether it’s to inform, inspire, witness, fact-check, testify, advocate, resist, nurture, celebrate, rejoice and/or heal.

The pandemic interrupted Sainte-Marie’s renew-and-regenerate vibe, but only temporarily. “When somebody kicks the anthill over, everything goes in different directions, and everybody is in survival mode and feeling disoriented,” says Sainte-Marie, who has been based in Hawaii since the late ’60s. She is intensely private about her home life. She has community, including her son, Cody, and her friends, but just like when she was a child, she’s still content to be on her own for long periods—and to spend a lot of time in nature and with her animals (she currently has two Siamese cats, named Anderson Cooper and Penuche).

For the first two months of lockdown, Sainte-Marie sat on the couch. A lot. Then her body began to ache, and she knew she had to make a change.

“I said, ‘Okay, I gotta be my own best friend here,’ ” she recalls. She started working out, including seniors’ exercise classes via Zoom. She began electric guitar lessons online because she’d always wanted to improve that skill set, but her hands were out of practice, so she picked up CBD lotion at the pharmacy, which has helped. “So now I’m playing better anyway, and I feel really good. I’ve got no aches and pains. I just try to be a good mom to myself sometimes, you know?” she says. “I don’t think women do that often enough.”

She also released her debut children’s book, Hey Little Rockabye, in 2020. It’s an illustrated lullaby for pet adoption; Sainte-Marie has devoted a lot of her downtime to working with the Humane Society of Canada. She’s also redistributing resources to other folks and has asked some of her friends to help her disburse funds in their communities, either directly to people in need or to help support grassroots efforts (like Idle No More) on the ground. “There are just so many falling through the cracks right now,” Sainte-Marie says.

Sainte-Marie performs in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in 2016. (Photo: Getty.)

She’s been sharing her resources in other ways as well, performing online throughout the pandemic, and has had to quickly adapt to 21st-century DIY home video production, sound design and self-direction. Sainte-Marie even continues to make music over the internet, remotely recording a song with Serena Ryder for Ryder’s new album, and collaborating on a track with Mohawk DJ and music producer DJ Shub, whose real name is Dan General. Both are thrilled to be working with one of their musical heroes.

“If you are an Indigenous artist, Buffy is the one person that has broken down so many doors and barriers for us,” General says. “Growing up, I didn’t know what activism was; through her music, she taught me who I was and what I had to fight for.”

Ryder calls her collaboration with Sainte-Marie one of the greatest honours of her career. “I’ve been just so taken aback at how down-to-earth, kind and humble she is,” she says. The pair first crossed paths at the Montreal International Jazz Festival in 2008. “She met me with such warmth and grace—like we were old friends,” Ryder recalls. “She seems plugged into some source—something that is steering her ship. There’s a wisdom and divinity in her voice and words that have inspired me to tap into my own connection to spirit.”

General is similarly awestruck by Sainte-Marie’s range and vision. “It’s very rare to see artists evolve,” he says. “[They] get too comfortable doing the same thing over and over. Buffy is not one of those artists.”

Indeed, innovation and new information are two of Sainte-Marie’s biggest thrills. She knows exactly who she is and what her values are, but she’s always embracing new iterations of herself. Nor does she show any signs of slowing down just because it’s what’s expected of an 80-year-old woman. Until our conversation, she hadn’t given her milestone birthday a single thought.

“I always figured I would die young, so I better hurry up and do whatever it was I was planning to do. And then, whoa, holy smokes, 10 years went by, and then another 10 years, and they just keep on coming!” Sainte-Marie says with a laugh. “Like most things, it’s not what you imagine. I feel pretty much exactly the same way that I did years ago. I mean, there are still bullies in the world, there are still exciting, wonderful people and things in the world, and I’m still here.”