How workers become seduced by the cult of 'optimal busyness'

The consultant was on her way to a demanding client meeting when she realized she had had a miscarriage. But she did not interrupt her day. Instead, she went on to complete the meeting at her client's offices.

The woman, who works at an elite professional service firm in London, was one of the professionals we interviewed as part of our recent study of the work life of highly educated professionals.

When we began our study in 2014, we set out to investigate how workers in demanding jobs managed their work-life balance. But soon after we started the interviews, we realized we needed to revise our focus, because it became clear that our interviewees were not seeking to balance their work and private life.

Instead, we found these workers were driven by a compulsion to be busy at all times, which meant they were also willing to sacrifice their family lives in important ways.

As one of our participants told us: "You become a little bit of a junkie for a deadline and work. It's quite hard to switch off."

While a common narrative in research and the media is that people want to slow down their lifestyles these days, our findings reveal a strikingly different story.

The desire to work fewer hours among our interviewees was uncommon. Instead they were in pursuit of something else: "optimal busyness."

The quest for optimal busyness

We interviewed 81 people who work in some of the biggest consulting and law firms in London. Half of the workers were women, half were men, and nearly all of them had at least one child. All of the professionals we interviewed suffered from time famine—constantly having too little time to do what they had to do.

To deal with this problem, they were drawn toward a compelling state of busyness, one in which they felt in control of their time. We call this "optimal busyness"—an attractive, accelerated temporal experience that is difficult to achieve and maintain.

Overall, we identified three different kinds of experiences of busyness: optimal busyness, excessive busyness, and quiet time. Optimal busyness is an elating and enjoyable temporal flow in which the workers felt at their best and most productive. This buzzing feeling gave them adrenaline and positive energy, which was exciting. When they were in this state, they felt nothing could stop them, and that they could, for example, save a company from going bankrupt.

Such an attraction toward busyness can be understood as a kind of status symbol or badge of honor, a phenomenon that has been described in previous research.

But we found that this drive went far deeper than mere social signaling. The desired buzzing feeling was itself inherently addictive. One participant told us: "I love the intensity of it, usually. I get a buzz out of it, that's why I do the job that I do. I like it."

We observed the pleasurable and positive state of optimal busyness often tipped over and became excessive. In such instances, professionals' feelings of being in control of their time vanished. This is where busyness became overwhelming and sometimes depressing.

When the energizing buzz of optimal busyness continued for too long without break, it became unbearable. Connection with family was often the first casualty. One participant went on a work trip and despite promises to call her family in the evening failed to do so—for the entire week.

We observed a similar pattern in the case of quiet time—that is, when the busy work period was suddenly interrupted by downtime, or typically, a holiday period. Quiet time was experienced as something undesirable and meaningless. It also caused boredom and even depression. The thought of a slower pace at work was a source of concern. One told us:

"When I don't have deadlines I get bored. I'm much less productive because I like working on adrenaline."

As well as interviewing busy knowledge workers, we also spoke to some of their partners. One partner said:

"My wife is terrible. If she wakes up to go to toilet in the middle of the night, she checks her emails—even at 3 AM."

The conditions for optimal busyness

On one hand, workplaces produce the conditions that drive the quest for optimal busyness. We identified a number of mechanisms that did this, including unrealistic deadlines, performance metrics, time sheets, and the working culture itself—companies and peers expected everyone to be available to work at all times via their smartphones.

The firms we studied are elite institutions that hire the best university students with the highest grades. New recruits wanted to survive the impossible pressure because they knew it was the only way to get a promotion or to become an associate in the company. Busy working culture soon absorbed them and normalized unnatural working hours.

On the other hand, we found individuals themselves were also creating the conditions for optimal busyness. Some boosted their capacity to work with coffee, drugs, or physical exercise. Others went as far as isolating themselves in a hotel room so they could work without interruptions.

A common strategy was for workers to think: "This is only a short period and once I am through I will relax." For most, the relaxation never happened.

A culture of overwork

For decades, scholars have observed the persistence of long working hours, overwork, and time famine. These problems are ingrained in many professional work contexts, not only in consulting, audit or law firms.

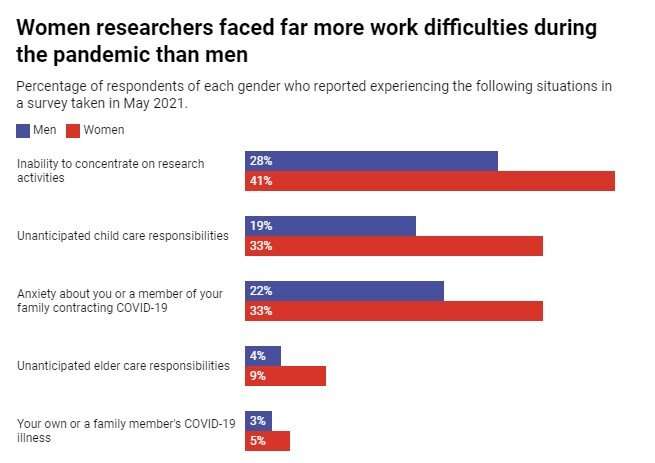

Academia is another striking example: studies consistently show that researchers' poor mental well-being is linked to increased performance expectations, competitive ethos, and meticulous metrics that produce non-stop busyness.

Our research offers a new way of understanding this phenomenon. The quest for optimal busyness is a vicious cycle. However, until recently there has been limited research that would uncover our everyday experiences of time and how they can take a hold of us.

The individuals we studied, albeit in an arguably extreme context, were often unaware what was happening to them. Perhaps it is time for us all to reflect on how and why we are so addicted to feeling busy.