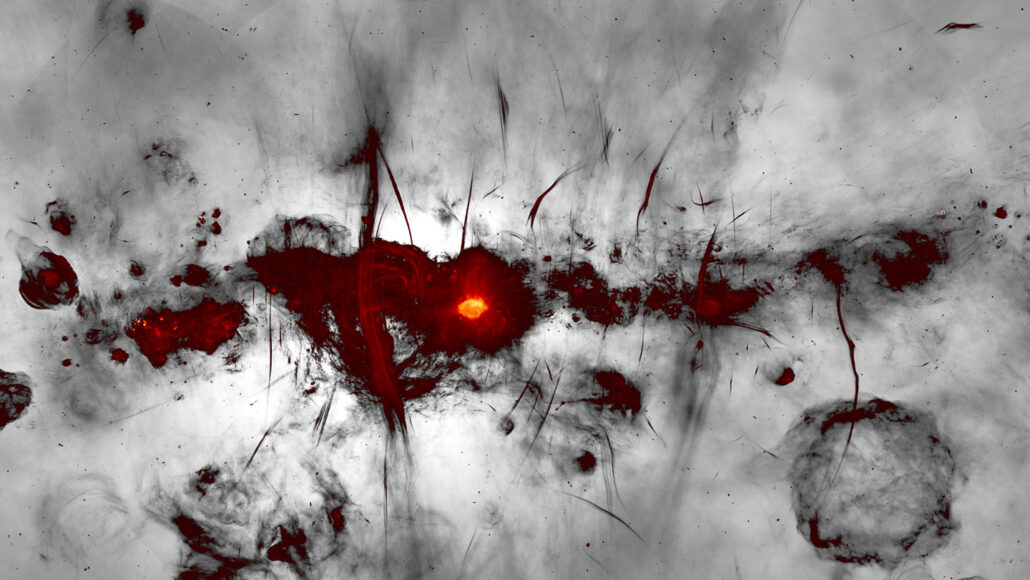

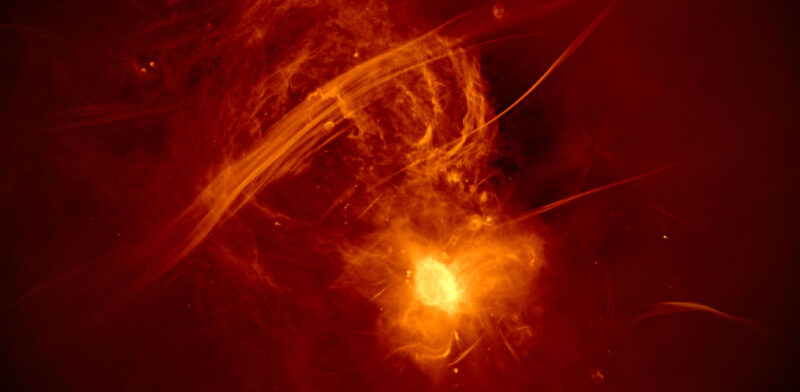

Wispy filaments accent the brightest spot, supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*

The MeerKAT telescope array in South Africa provided this image of radio emissions from the center of the Milky Way. Stronger radio signals are shown in red and orange false color. Fainter zones are colored in gray scale, with darker shades indicating stronger emissions.

I. HEYWOOD/SARAO

By Lisa Grossman

FEBRUARY 3, 2022 AT

An image that looks like a trippy Eye of Sauron or splatter of modern art is actually a new detailed look at the Milky Way’s chaotic center, as seen in radio wavelengths.

The image was taken with the MeerKAT radio telescope array in South Africa over the course of three years and 200 hours of observing. It combines 20 separate images into a single mosaic, with the bright, star-dense galactic plane running horizontally. The MeerKAT team describes the image in a paper to be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

MeerKAT captured radio waves from several astronomical treasures, including supernovas, stellar nurseries and the energetic region around the supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s center (SN: 8/31/21; SN: 9/17/19). One puffy supernova remnant can be seen in the bottom right of the image, and the supermassive black hole shows up as the bright orange “eye” in the center

Other intriguing features are the many wispy-looking radio filaments that slice mostly vertically through the image. These filaments, a handful of which were first spotted in the 1980s, are created by accelerated electrons gyrating in a magnetic field and creating a radio glow. But the filaments are hard to explain because there’s no obvious engine to accelerate the particles.

“They were a puzzle. They’re still a puzzle,” says astrophysicist Farhad Yusef-Zadeh of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., who discovered the filaments serendipitously as a graduate student.

Previously, scientists knew of so few filaments that they could study the features only one at a time. Now MeerKAT has revealed hundreds of them, Yusef-Zadeh says. Studying the strands all together could help reveal their secrets, he and colleagues report in a paper to be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. “We’re definitely one step closer to seeing what these guys are about,” he says.

The observatory released the data behind the imagery as well, so other scientists can run their own analyses on it. “There’s going to be a lot of science coming,” Yusef-Zadeh says.

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at feedback@sciencenews.org

CITATIONS

I. Heywood et al. The 1.28 GHz MeerKAT galactic center mosaic. arXiv:2201.10541. Submitted January 25, 2022.

F. Yusef-Zadeh et al. Statistical properties of the population of the galactic center filaments: The spectral index and equipartition magnetic field. arXiv:2201.10552v1. Submitted January 25, 2022.

About Lisa Grossman is the astronomy writer. She has a degree in astronomy from Cornell University and a graduate certificate in science writing from University of California, Santa Cruz. She lives near Boston.

Related Stories

ASTRONOMY

Giant radio bubbles spew from near the Milky Way’s central black hole

By Emily ConoverSeptember 11, 2019

ASTRONOMY

How scientists took the first picture of a black hole

By Maria TemmingApril 10, 2019

SPACE

Milky Way’s black hole seen in new detail