Stephan Wilkinson

An upended Allied Renault FT-17 tank rises from a muddy frontline trench near Saint-Mihiel, France, in July 1918. (Library of Congress)

Irascible, overbearing, argumentative, condescending, a fan of woo-woo occultism and, ultimately, a Nazi sympathizer, J.F.C. Fuller was nevertheless a foresighted tactician

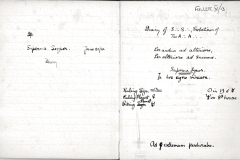

Major General John Frederick Charles Fuller was, during World War I and through the early 1930s, the British army’s tank warfare go-to guy. He was the man who taught the Wehrmacht how to blitzkrieg, George Patton how to rumble and the Israelis how to kill Syrians. Yet he was an absolute un-Pattonlike, don’t-mistake-me-for-Bernard Montgomery, I’m-no-Heinz-Guderian staff officer. The quintessential egghead, “Boney” Fuller was a tiny man with a modicum of actual combat experience whose bearing, manner and attitude were fully represented by his nerdy nickname.

Irascible, overbearing, argumentative, condescending, a fan of woo-woo occultism and, ultimately, a Nazi sympathizer, J.F.C. Fuller was nevertheless a foresighted tactician and imaginative military theorist. He would have been hard-pressed to take a rifle squad into action, yet he did something few other professional officers at the time bothered with: He thought about how battles should be fought. Thought so long and hard, in fact, that he became what the Brits love to call “too clever by half.”

Fuller failed to get into Sandhurst on his first try because he was too short (5-foot-4), too wispy (117 pounds at age 18) and had too small a chest (boney, presumably) to meet the British military academy’s standards. Second time around he got in, though he later admitted, “I took no interest whatever in things military.” Fuller preferred to read classics and write letters to his mother, yet he eventually secured a commission in the Oxfordshire Light Infantry.

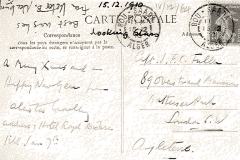

About his first action, in the Boer War, Fuller observed: “We knew nothing about war, about South Africa, about our eventual enemy, about anything at all which mattered and upon which our lives might depend. Nine officers out of 10—I might say 99 out of every 100—knew no more of military affairs than the man on the moon and do not intend or want to know more.” Fuller was so contemptuous of his fellow officers that, he wrote his mother, he even loathed playing cards with them during the voyage to South Africa. “That biped is a great deal too uninteresting for me,” he sniffed, adding, “The army…needs primitive men who enjoy the heirlooms of prehistoric times such as hunting, shooting, etc.”

Fuller saw his first real fighting in the Transvaal. He wrote his mother about a friendly fire incident in which a native trooper was wounded in the forehead. Fuller fed the man whiskey while trying to stuff his brains back in with the handle of a mess kit fork. His words reveal his lifelong racism: “Any ordinary civilized individual would have fallen down dead at once, but I suppose these semi-savages use their brain so little that it doesn’t matter much if they lose a part of it.”

The best months of Fuller’s Boer War came when he was put in charge of 70 black scouts and given a 4,000-square-mile area of only partially pacified countryside to patrol. His recon platoon engaged in casual firefights, took and interrogated prisoners, raided, scouted for regular army units and generally operated independently. It was dangerous work, for the Boers particularly hated Brits who led the despised “kaffirs,” and captured officers could expect to die in unpleasant ways.

The experience was for Fuller an on-the-job tactical education. It taught him about field operations—particularly frontal and flank attacks and whether to envelop or penetrate an opposing force—in a way Sandhurst never could. His South African foray instilled in Fuller two ideas that would become cornerstones of his tactical thinking: 1) mobility is all-important, and 2) a rapid, deep, penetrating attack is far more effective than the traditional slow-paced, beat-your-head-against-a-wall frontal assault.

When Fuller returned to England after a brief posting to India (where he stoked his fascination with Eastern religion and mysticism), he resolved that the sweatier side of army life—drilling, marching, maneuvering—held no appeal for him and decided to escape into staff work. In 1913 he was accepted into the Staff College at Camberley, again on his second try. Fuller almost immediately got into trouble for trying to amend the army’s sacrosanct operating handbook, the Field Service Regulations. The FSR basically stated that war was simple, fighting principles were not particularly numerous or abstruse, and Napoléon pretty much knew everything that needed to be known.

Perhaps due to his reputation as a prima donna and troublemaker, at the 1914 outbreak of war Fuller was assigned as a minor General Staff officer, while his schoolmates were sent to the front (where many were killed). Among Boney’s crucial tasks, he reorganized the filing system at his base, developed a sheep-evacuation plan in the event of a German invasion, and determined whether and how to deprive such invaders of alcohol in the area’s pubs. In March 1915, he finally managed to get into the action by insulting his commanding officer so thoroughly that the man shipped him out in retribution.

What Fuller found in France was the stalemate that would persist for most of the war. Frontal attacks were useless, as both sides fielded machine guns. Flanking attacks were impossible, as frontline trenches extended across the Continent from the Atlantic to Switzerland.

Fuller advocated a style of warfare based on mobility and penetration—that is, breakthrough on a limited front. (Twenty years later, Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht would use those principles to develop its blitzkrieg concepts.) Another elementary principle on which Fuller predicated his style of war was mass: If you don’t outnumber your enemy, you probably can’t outfight him. “Do not let my opponents castigate me with the blather that Waterloo was won on the playfields of Eton,” he later wrote, “for the fact remains, geographically, historically and tactically, whether the Great Duke [of Wellington] uttered such undiluted nonsense or not, that it was won on fields in Belgium by carrying out a fundamental principle of war, the principle of mass; in other words by marching onto those fields three Englishmen, Germans or Belgians for every two Frenchmen.”

It was the tank, however, that would establish Fuller’s reputation as a tactician. So much so that some think he invented the modern armored vehicle, though in fact he became “an armor guy” well after Sir Ernest Swinton conceived the vehicle, after its first combat test at the September 1916 Battle of the Somme, and after Swinton and others had already developed and written about tank tactics.

Fuller later recalled his own epiphany. He’d gone to Yvranch, France, home of the army’s Heavy Section, as Tank Corps was then called, to watch the demonstration of a remarkable new weapon. (In fact, about all the Heavy Section was doing in those days was putting on daily maintenance-intensive dog-and-pony shows for visiting officers, sending its crude tanks to trundle over berms, cross trenches and, of course, crush trees like matchsticks.) “Everyone was talking and chatting,” Fuller wrote, “when slowly came into sight the first tank I ever saw. Not a monster but a very graceful machine with beautiful lines.…Here was the missing tool of penetration, the answer to the dominance on the battlefield of small-arms fire.” Fuller had found the antidote to the all-powerful machine gun.

Fuller’s first actual tank operation was the April 1917 Battle of Arras. As a demonstration of the tank’s capability the operation was a failure, at least in part because tankers ignored Fuller’s advice to deploy en masse and instead fed the tanks—mostly clapped-out training vehicles shipped from England—into battle a few at a time. Nor did it help that the army insisted on a traditional pre-attack artillery bombardment, a tactic anathema to Fuller, as it both eliminated any element of surprise and so thoroughly chewed up the ground that many of the tanks were immobilized.

The Battle of Cambrai in November and December 1917 was the Tank Corps’ greatest wartime success, as it punched a horde of tanks through the Hindenburg Line in a stunning example of Fuller’s penetration tactics. Fuller had wanted to lead the central charge, but his commander, Lt. Col. Hugh Elles, turned him down and directed the battle himself from his tank “Hilda,” becoming a fleeting national hero as a result.

Still, Cambrai wasn’t a clear-cut enough victory to establish Tank Corps as part of the varsity. Field Marshal Douglas Haig instead relegated tanks to a defensive role, much to Fuller’s chagrin. The iron monsters were strung out along a 65-mile front, either dug into pits or otherwise fortified—parked pillboxes, in effect—where “this beast would squat and slumber until the enemy advanced,” Fuller later mocked, “when it would make warlike noises and pounce upon him.”

Fuller’s finest wartime moment was the promulgation of his Plan 1919. Believing World War I would continue into 1919, he suggested victory with a single penetrating, surprise, mass tank attack aimed not at killing lots of German soldiers but at reaching and killing the enemy “brain”—the rear-area command-and-communications infrastructure—and thus paralyzing the body. But Fuller’s most meaningful tactical concept came to naught, as the war ended in November 1918. Had it continued, Fuller today might be as widely known as Guderian, Montgomery and Patton.

Britain’s hidebound high command seemed to learn little from World War I, their American counterparts perhaps only a bit more. The military remained convinced that wars were won by men clad in woolen uniforms hiding behind rocks and shooting bullets at one another and that despite the growing civilian predilection for cross-country travel in gasoline-powered automobiles, mobility of armies was still best provided by horses. Few seemed to realize that armor trumped wool and machinery was stronger than muscle. Part of the problem was that professional officers liked horses and loathed greasy, smelly machinery. Even airplanes met with their disdain.

Through the 1920s, as Fuller grew increasingly disenchanted with the military and his inability to bring about real tactical reforms, the military became equally disenchanted with Fuller. The final straw was the “Tidworth Affair,” which began when the British army gave Fuller the plum command of an experimental tank force at Tidworth, on the Salisbury Plain. The posting, which marked the tactician’s last chance to champion his armored doctrine, turned sour when he voiced a variety of small-minded ultimatums, such as demanding a full-time secretary and refusing to “waste his time” commanding an infantry unit attached to the tank force. To top things off, he petulantly threatened to resign, which would have been a PR disaster for the army, as Fuller had far stronger support among the popular press than he did among the officer corps. The army managed to talk him out of quitting.

But instead of taking in Tidworth, Fuller was again sent to India on a minor fact-finding mission and was never again offered a command. In 1933, at the age of 55, Fuller retired as a major general. Biographer Anthony John Trythall summed up his turbulent career: “And so ended, a few years before what will almost certainly prove to have been the largest and longest mechanized war of all time, the military career of Britain’s most experienced and able tank officer, the victim of his own brilliance and energy, and of his own inability to trim his words and actions to the winds of political reality and human frailty.…He was…too clever, too rigid, too intellectually arrogant and self-reliant to be highly successful in a military career.”

Following his army retirement, Fuller became deeply involved with Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (not a completely unexpected development, given that Fuller was a Germanophile, a racist and an anti-Semite whose preferred boyhood nickname was “Fritz”). He visited Germany frequently and spent time with Hitler, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Rudolf Hess, all of whom he found “charming.” Fuller was one of only two British guests at Hitler’s 50th birthday party, in April 1939, and it was at that event he apparently spoke some of the most notorious words ever attributed too him.

After a three-hour parade of the thoroughly motorized, armored Wehrmacht, Hitler greeted Fuller on the receiving line and said, “I hope you were pleased with your children.” Fuller is said to have replied, “Your Excellency, they have grown up so quickly that I no longer recognize them.” The Germans—particularly panzer commander Guderian—would later largely credit Fuller’s writings with their development of blitzkrieg tactics, though historians debate whether the defeated Guderian meant this more as postwar politeness than praise.

While Fuller realized that war with Germany would almost certainly erupt again, he deluded himself into thinking that white brothers under the skin would wage chivalrous battles, eventually settle on a winner and shake on it, “for chivalry was born in Europe,” he naively wrote.

While the government interned most members of the British Union of Fascists upon the 1939 outbreak of war, Fuller was left alone, probably because Winston Churchill intervened on his behalf. Yet Fuller loathed Churchill, of whom he once wrote to his friend Basil Liddell Hart, “The war as it is being run is just a vast Bedlam with WC as its glamour boy; a kind of mad hatter who one day appears as a cowpuncher and the next as an air commodore—the man is an enormous mountebank.”

In the 1930s Fuller had embarked upon a second career as a writer, ultimately penning some 45 authoritative books and hundreds of popular-press articles and scholarly papers. He wrote about everything from war to yoga (the latter extremely avant-garde at the time) and became a precursor of today’s retired generals anxious to freelance as media talking heads. Indeed, Fuller was Newsweek’s “military analyst” during much of World War II.

For all his foibles and failings, Fuller was a visionary. In the early 1930s he predicted, as Anthony Trythall wrote, “future armies would be surrounded by swarms of motorized guerillas, irregulars or regular troops making use of the multitude of civilian motorcars that would be available.” Fuller also mused that one day “a manless flying machine” would change the face of war. Early on he was intrigued by the development of radio, not only for communication but also as a way to control robot weapons. He also thought then-primitive rocket technology would one day lead to the development of superb anti-aircraft weapons.

And as early as the 1920s, Fuller was a proponent of amphibious warfare. He envisioned a naval fleet “which belches forth war on every strand, which vomits forth armies as never did the horse of Troy.” Indeed, he foresaw future navies as being entirely submersible. On the negative side of the balance sheet, Fuller also championed the military use of poison gas, particularly when spread by airplanes. Even as late as 1961, with the publication of his book The Conduct of War, he blamed resistance to chemical warfare on “popular emotionalism.”

If Fuller had a fatal flaw as a tactician, it was that he derided the importance of putting infantry “boots on the ground.” To him, combat was simply a matter of wool uniforms versus steel armor—and that seemed to him a no-brainer. Of course, Fuller had failed to consider the development of portable, shoulder-fired and helicopter-borne antitank weaponry.

Maj. Gen. J.F.C. Fuller, CB, CBE, DSO (Ret.) died on Feb. 10, 1966. Had he lived another 16 months, he’d doubtless have gained considerable satisfaction from Israel’s total rout of the Egyptians, Syrians and Jordanians in the June 1967 Six-Day War, using Fuller-doctrine tank tactics in what was later dubbed “the Jewish blitzkrieg.”

“Boney” Fuller was indeed a prophet—albeit a cantankerous, irritating and bigoted one—in his own time.

For further reading, Stephan Wilkinson recommends: “Boney” Fuller: Soldier, Strategist and Writer, 1878–1966, by Anthony John Trythall, and Fuller’s own The Conduct of War, 1789–1961.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/JLQQ7OUFB7R3437QSPKYWQXAZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/DPHZAULFC2BKIRDUOLKIYQJCMA.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/MA2CJAAOX2UYEAEXLXWVDE5HAQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/A445GF6VN3U4LHNDGRCI6HGLO4.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/PWE62B5ZILMQBTDQKPWHIZZJZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/U6K77JXYVI23OQ7KYL3KJ5C5SE.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/GDPD32YRDXVPQOC7D35T567ZMA.jpg)