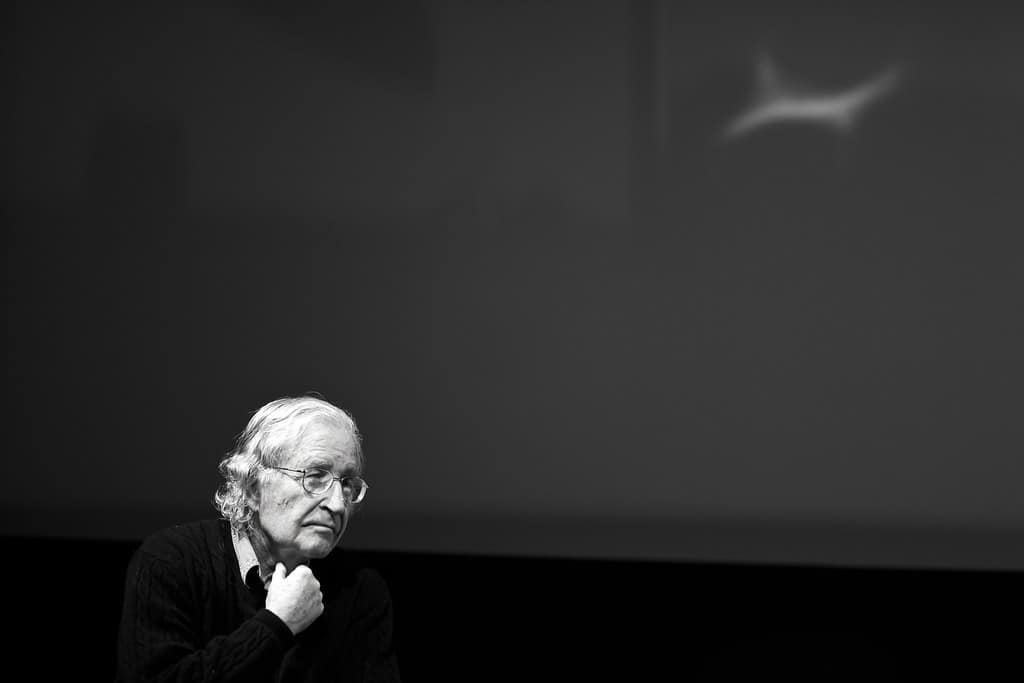

The father of modern linguistics speaks exclusively to The London Economic about Donald Trump, Jeremy Corbyn and most pressingly: the climate crisis.

2021-04-24

Noam Chomsky is among the world’s most eminent political rebels. For decades, his stark criticisms of the United States’ foreign policy have troubled presidents, both Republican and Democrat.

Just last year, the self-proclaimed anarchist called Donald Trump “the worst criminal in history” for his refusals to act on the climate crisis in a controversial interview with the socialist publication Jacobin Magazine.

Former president, Barack Obama, didn’t get off lightly either. He was in Chomsky’s bad books for waging a targeted “global assassination campaign” (Obama is estimated to have carried out 1,878 drone strikes over eight years) during his time as leader.

Even Joe Biden, who only took up office in January this year, was reprimanded early in his presidency for adopting Trump’s policy on Iran with “virtually no change”. Biden’s appointment of Richard Nephew – author of the book The Art of Sanctions – as Iran envoy particularly concerned the renowned academic who says the sanctions on Iran were “illegitimate in the first place”.

The father of modern linguistics

You’d think the 92-year-old would be tired of talking politics by now, but if YouTube is anything to go by, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The video sharing website’s recent pages are full of clips of him chatting with university students (he’s still a Laureate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona and Institute Professor Emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology or MIT), debating well-known journalists and looking bewildered as entrepreneurs ask questions about his beard.

After three years’ worth of emails, we sit down to chat on Zoom (his video calling preference). When he appears on the screen from his home in Tucson, Arizona, he looks, with his wispy grey hair and long and unkempt beard, like a modern-day Plato – sat in front of a packed bookshelf, displaying only one photo of him and his wife. Over the course of nearly an hour and a half, we discuss everything from activism and internationalism, Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, to Jeremy Corbyn and Joe Biden, as well as nuclear war and perhaps the most pressing matter of all: the climate crisis.

Born in Philadelphia in 1928, to say the ‘father of modern linguistics’ – a name given to him for his revolutionary theories in the field – has lived a full life would be the understatement of the century. He was brought up by Jewish immigrant parents, William (Ze’ev) Chomsky and Elsie Simonofsky, during the Great Depression – his father fled the Russian Empire to escape conscription in 1913. He listened to Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies over the radio as WW2 unfolded when he was a boy and rose to prominence in his 20s and 30s during the Vietnam War for his anti-war activism, which almost landed him in prison. “I was an unindicted co-conspirator in a federal trial and on track to be the main target of the next.”

The veteran activist also featured on Richard Nixon’s opponents list – an extension of his enemies list derived from prominent public figures (actors, academics, politicians etc.) he thought could be a threat to his presidency. But it was way before all of this that the professor became political.

“When I was four or five years old, I was beginning to think about these things [politics], and it never changed. I grew up in the depression. My early childhood memories were things like miserable people coming to the door trying to sell rags, women’s strikers being attacked by security forces. I was surrounded by things like that.”

Anarchist libertarian

It wasn’t just gloomy lived experiences that influenced his early political beliefs. His family played a big part too. Although his mother and father were centre-left politically, his uncle was more radical and had “been through every political party”. At 12, a young Noam would stay with him and his wife at the weekend. During his visits, he’d go to his uncle’s newsstand and listen to radical activists, some of whom had fled the Spanish Civil War. He’d spend the rest of his time dipping between anarchist bookstores and devouring political literature passed around Union Square – a hive for radical politics at the time.

Since establishing his views as a child, they’ve rarely wavered. He’s an anarchist-libertarian (an anti-authoritarian wing of the socialist movement) and has been since he cares to remember. When I ask him how he’s managed to stave off conservatism or cynicism, he says:

“I didn’t see any reason to be [more conservative]. My early beliefs seemed to be only partially formed; of course, they developed much more afterwards, when I learned more, but they seemed to basically be on the right track.”

When I ask him personal questions such as this, he’s polite and respectful, but his answers are curt. It’s as if he knows that our time in every sense of the word – is limited, and he’d prefer to reserve his energy for important subjects. However, he flows freely from one long, cultivated soliloquy to another discussing things like democracy, activism and the planet’s future. I guess it’s to be expected of a world-renowned linguist that’s dedicated his life to academia.

Chomsky is an exceptional scholar. He went to the University of Pennsylvania at 16 and later became a leading professor in linguistics. The author has also given speeches at events around the world and continues to do so virtually.

More recently, he co-authored a book with economist Robert Pollin, ‘Climate Crisis and the Green New Deal’, examining how to save the world from the climate crisis by laying out practical economic, humanitarian and technical solutions. His position on the topic is both clear and candid.

“We have maybe 20 or 30 years to see if human civilisation can survive, and we’re not doing it now. If we fail, if this generation fails, it’s basically saying, ‘it was nice having humans around for a couple of 100,000 years, but it’s over.”

“Lunacy, outright lunacy”

He’s talking about reducing carbon emissions to prevent a hothouse earth scenario, which would see the world hit its highest global temperature of any time in the past 1.2million years, making it, in his words, “unliveable”. Climate crisis is why the Paris Climate Agreement was set up in 2015. The International Treaty, signed by nearly 200 countries, aims to reduce carbon emissions and keep global temperatures well below 2.0C. However, Chomsky insists, “we’re nowhere meeting the promises.”

I ask him for his thoughts on another topical issue: nuclear weapons. More specifically, Boris Johnson’s plans to lift the cap on Trident (Britain’s nuclear deterrence). If reports are correct, the Prime Minister plans to increase nuclear warheads by 40%, which could break international law. The UK is a signatory of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) – a commitment for the government to gradual nuclear disarmament.

Is it dangerous?

“I wouldn’t say it’s just dangerous; it’s lunacy, outright lunacy. I mean it’s ludicrous for Britain to have a nuclear force altogether. It doesn’t defend Britain. In fact, it makes it a target; it contributes nothing to security. It’s a prestige thing. And along with heating the climate, nuclear war is a comparable threat, it’s a serious threat, very little discussed, but anyone who’s anywhere near the arms control community knows very well this is an extremely serious and growing threat.” he says.

The nonagenarian doesn’t think Johnson’s move will lead to an escalation from other countries because, in his words, “Britain no longer has the global role it once did”. He says the UK is now a “junior partner to the United States” – something he thinks will be accelerated because of Brexit. As his eyes flicker – perhaps as a signal of irritation – he moves on to Trump.

“During the Trump years, one of his great contributions was to tear to shreds the arms control regime, which had been painstakingly built up over 60 years, going back to Eisenhower. Piece after piece was dismantled. Trump was a wrecker,”

Chomsky isn’t a fan of Trump, he says “the most serious crimes he committed is the destruction of the acceleration of the use of fossil fuels and the elimination of regulatory apparatus. There’s nothing in comparison to that fact. And to be honest, and frank, that’s the worst crime in the history of the human race.”

I ask if he thinks Boris Johnson is going down a similar route.

“It’s not identical, it varies, but it’s too similar for comfort. I think developing the nuclear facilities is a case in point.”

“If Corbyn had been elected, Britain would be pursuing a much more sane course”

While we’re on the subject of nuclear deterrence, I can’t help but ask about Jeremy Corbyn, who, depending on political leanings, was either the biggest threat to world peace or the saviour of humankind.

Would the world have been a safer place had Corbyn won the last general election in terms of nuclear threat?

“I think if Corbyn had been elected, Britain would be pursuing a much more sane course. I think his general positions were very reasonable. And I think that’s probably the reason for the extraordinary attack on him pretty much across the spectrum, with mostly fabricated charges of antisemitism. Anything that could be thrown at him was, it was a major assault. Again, pretty much across the spectrum, The Guardian, right-wing press, ‘we got to get rid of this guy’.

“I think that’s a sign, a reflection of the fact that he had very reasonable proposals. He was also doing something dangerous, he was trying to turn the Labour Party into an authentic political party, one that’s based on its constituents, not some bureaucracy somewhere that runs it and tells people how to vote. That’s scary. We don’t want to have authentic, popular based political parties around, they could be out of control.”

Although there is no doubt, the Labour Party has had serious problems with antisemitism. Last year, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) identified “serious failings in leadership and an inadequate process for handling antisemitism complaints across the Labour Party.” The 130-page report went on to conclude that “there were unlawful acts of harassment and discrimination for which the Labour Party is responsible.” The former Labour leader was embroiled in an antisemitism row of his own for appearing to support a graffiti artist whose antisemitic mural was removed from a wall – something he later apologised for.

I bring up the genuine concerns raised regarding the Labour Party’s and antisemitism, which some felt were dismissed by Corbyn.

“If you look at the facts, the Tory party has more antisemitism than the Labour Party. There’s something there, you know, you should deal with it. But it’s not even within shouting distance of the way the issue was presented. By now, there’s pretty careful analyses of it. And I think if you look at them, you find what we know in advance. Yes, there’s antisemitism in England. That’s a bad thing. We should deal with it. But it’s not in the Labour Party any more than anywhere else, probably less.

“But compared with, say, islamophobia, it doesn’t even come close. Okay, that’s acceptable. You’re allowed that. In fact, if you look at the famous international Holocaust Remembrance Association’s statement on antisemitism, which everybody’s supposed to accept, just take its provisions and think about them for a minute. It follows that almost everybody’s a hysterical islamophobe. The charges of what they call indications of antisemitism if you apply that to attitudes towards Islam and Muslims, it cuts a very wide swath.”

The current IHRA statement on antisemitism from its website reads:

‘Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.’

Chomsky, who has previously spoken of being subjected to antisemitism as a child, finishes with “antisemitism shouldn’t be vulgarised and politicised, turned into a weapon. It’s too serious for that.”

“Antisemitism shouldn’t be turned into a weapon”

Keir Starmer, the current Labour leader, declared that tackling antisemitism was his first priority as Labour leader. He followed through with his word when he sacked Rebecca Long-Bailey in summer 2020 for sharing an article that contained antisemitic conspiracy theories. Corbyn was later suspended himself for sharing a statement 30 minutes after the EHRC report claiming the scale of the antisemitism problem had been “overstated for political reasons”.

Starmer has since faced criticism from large swathes of dedicated Corbyn supporters, many of which feel the party is moving to more centre-ground and not acting as serious opposition to the current government. Those more sympathetic to the challenges he’s faced early in his premiership – namely a global pandemic – believe he’s adopting a similar strategy to Joe Biden by waiting until his opponent fails.

Wary that our time has run over by 36 minutes already, I ask if Starmer’s strategy is a good one.

“It’s a good strategy if you want to turn the Labour Party into a junior partner of the Tories. Pretty much like what Tony Blair did, it used to be called Thatcher light. If that’s what you want, fine. If you want a Labour Party that actually represents the working people of England, middle-class people of England, pursue their interests, it’s not the way to do it. It depends on what your goals are. It looks to me that Starmer’s is pretty much dismantling the activist Labour Party that the Corbyn people were trying to develop.”

It’s a statement that will thrill Corbynistas but probably won’t surprise Starmtroopers either. After all, Chomsky himself said he’d back Corbyn during the 2017 election campaign, and he’s hardly someone that’s tempted by moderate politics, although he did endorse Joe Biden.

Though he’s happy about the path he’s going down regarding the climate crisis, he’s not convinced it’s entirely original. “Biden’s programme is much better than any predecessor, not because of a religious conversion, because of very significant activist pressures, which have made a difference.”

After just over one hour 20 minutes, the interview draws to a close. He politely explains he has got to go, more appointments. I steal a second to ask one final question. Where does he see the world in 2050? His answer is unapologetically Chomsky-esque.

“Well, there’s one thing we can say, either we will have reached net-zero emissions by 2050, or we can pretty much say goodbye to each other.”

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin’s book, ‘Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal’ is available here.

.png)