JAMES RETHERFORD: BOOKS | Judy Gumbo’s ‘Yippie Girl’

Combating authoritarian repression with absurdist political theatre.

Listen to Thorne Dreyer‘s interview with ‘Yippie Girl’ Judy Gumbo on Rag Radio, here.

Listen to Thorne Dreyer‘s interview with ‘Yippie Girl’ Judy Gumbo on Rag Radio, here.

As Kris Kristofferson sorta said, “[S]he’s a walkin’ contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction.” Such is noted Sixties troublemaker Judy Gumbo’s part myth/part romance/part Bildungsroman, Yippie Girl: Exploits in Protest and Defeating the FBI, where “Yippie is a state of mind.”

As all good Marxists know, to call something a contradiction is not a criticism but a description of historical process, and free-form myth-making was a central feature of the Yippie creative strategy for combating authoritarian repression in the mid-Sixties/early Seventies. The Yippies can trace their taste for absurdist political theatre at least back to the Zurich dadaists of 1916. Our Marxism comes with an abundant measure of Grouchoism.

I am at least partly responsible for injecting myth into the cannons of Yippie literature. My 1970 work-for-hire bio-fable, Do It!: Scenarios of the Revolution, portrayed Jerry Rubin as the parabolic “child of America.” The opening line, “The New Left sprang, a predestined pissed-off child, from Elvis’ gyrating pelvis,” even alludes to the birth of the original Olympian wild child of myth and ritual … Dionysus, the patron saint of the Yippies.

So I am not surprised when Judy seeks to air out the musky closets of male-dominated myth-making with a fresh female look at the old tropes. In fact, I would expect nothing less from a woman of her fearlessness, intelligence, and character.

Judy Clavir was born June 25, 1943, in Toronto, the oldest daughter of immigrant Eastern European Jews. Her parents, Leo and Harriet, were dedicated, but secret, members of the Canadian Communist Party, and her father, who distributed Russian films throughout North America, frequently visited the Soviet Union. Her mother, Judy writes, lost her dedication to Stalinism and replaced it with booze, cigarettes, and anger.

Along with Anita and Abbie Hoffman, Nancy Kurshan and Jerry Rubin, Paul Krassner, Phil Ochs, Ed Sanders, Robin Morgan, Jonah Raskin, Stew Albert, and more, Judy was an original member of the Yippies, aka the Youth International Party.

Gumbo arrived in Berkeley in the fall of 1967 and shortly thereafter met a “blue-eyed blonde with curly hair” named Stew Albert, who would soon become her on-again, off-again, but mainly on-again co-conspirator, partner, and husband until his death in 2006.

Stew was also besties with Black Panther Party minister of information Eldridge Cleaver and Jerry Rubin, which gave Judy an intimate opportunity to watch the history of the Black Power movement and cultural revolution unfold. It also gave her the up-close and personal opportunity to learn how women, even movement women, are disregarded and marginalized into roles no different than that of the dominant white male-dominated capitalist society.

Judy received her Yippie surname from Cleaver, who liked to call Judy “Mrs. Stew.” When Judy objected, Eldridge said, “Alright then, I’ll call you Gumbo,” because to Cleaver, born in Arkansas, “Gumbo was a spicy Stew.”

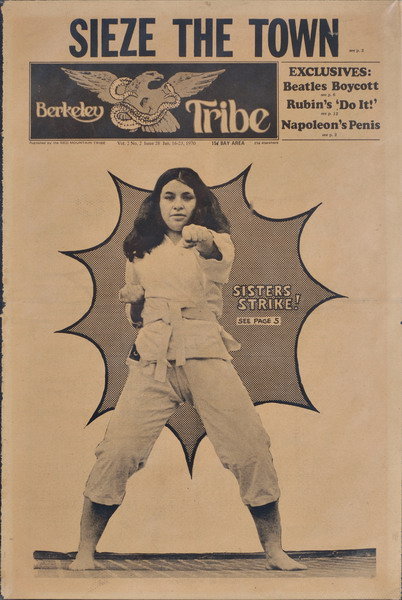

Gumbo navigated the ebbs and flows of Bay Area activism—as a trusted Black Panther ally, underground journalist, and later People’s Park insurgent—and then moved on, with Stew, to New York City, where she became part of the two-ring circus called Yippie!

And then, of course, Yippie! went to Czechago in August 1968, nominated a pig to run for president of the United States, was attacked and beaten by Mayor Richard Daly’s bigger and meaner pigs, and then put on trial for conspiracy to cross state lines to desecrate the nation’s political hog wallow.

During this time, our shameless lifestyles and anti-social ideas were the subject of perverse interest to federal authorities operating under the relaxed surveillance directives of J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO. Headed by FBI deputy director Mark Felt—later to be revealed as Watergate informant Deep Throat—the feds engaged in a long dirty laundry list of extralegal and outright illegal actions against people believed to have contact with the Weather Underground, who recently had successfully detonated explosive devices in the U.S. Capitol and the NYC police commissioner’s office, or to be working on the 1971 Mayday demonstrations in Washington, D.C.

The FBI moved my neighbor out of his roach-infested apartment into a nice hotel in order to station agents and listen through the wall as I painted my fireplace with acrylics, wrote bad poetry, and had absolutely no sex.

Even as I watched through my front-door peephole as men wearing London Fog overcoats came and went from the grungy sixth-floor walkup … Even as I returned home to find papers on my work space in disarray … Even as I summoned the nerve to creep out on the fire escape and peek through the next-door apartment window where glowing LED lights illuminated banks of reel-to-reel recording machines in the semi-darkness …

Even then I had trouble believing that I was being spied on by the United States government. Such was the nature of movement paranoia in those days.

About the same time, the feds had been caught red-handed placing a tracking device on Judy’s car. Not once but twice! Her home was broken into, and a listening device was installed there. Gumbo described the mind-dulling, evidence-denying effects of fear and paranoia with such clarity that I revisited those times and rediscovered that paranoia vanishes when light is shined into the dank holes where repressive plots are planned and waged by ruthless autocrats. One on the sources of that light was the underground press.

Quotes from Gumbo’s FBI files are sprinkled throughout Yippie Girl like an off-key Greek chorus. Their voices often lend an element of farce to the narrative, kind of like the phone call to the Keystone Kops that triggers all of the frolicking slapstick. I was reminded that while the government operative’s power to intimidate and repress was extensive, their stupidity and incompetence were indeed epic.

The result of this prolonged government farce was the nationwide Guy Goodwin grand juries of 1971, beginning after the FBI “kidnapped” Leslie Bacon from her bed at the Washington Mayday organizing collective, secretly transported her by auto across country to Seattle, and put her in front of a grand jury without legal counsel.

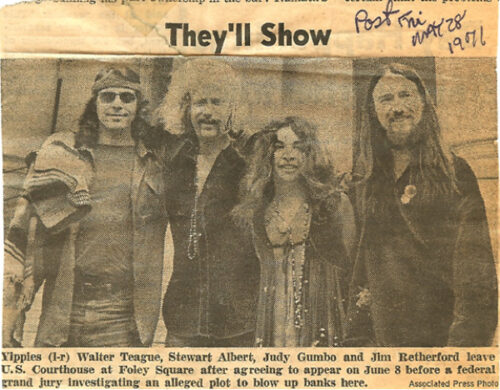

In NYC five movement activists were subpoenaed—myself, Sandra Wardwell (a Santa Barbara activist previously arrested after the burning of a Bank of America branch), veteran New York anti-Vietnam War organizer Walter Teague, and Judy and Stew. (A sixth individual, Chicago-born heiress Ellen Ruth Stone, was also subpoenaed, but after her billionaire father intervened, Stone’s subpoena was quietly quashed.)

Myth-making is successful when the myth is far more compelling than the real story. What actually transpired in and around the federal courthouse at Foley Square on June 8, 1971, as the five subpoenaees arrived to face Guy Goodwin’s grand jury was the stuff of collective Yippie legend.

What I participated in, under the towering granite and marble foyer outside the grand jury chambers, was a quintessentially Yippie counteroffensive against the Nixon administration’s war on dissent. It was two-thumbs-up Theatre of the Absurd.

The subpoenaed witnesses came to the courthouse dressed up in crazy-ass costumes and dared Goodwin to call us before his geriatric grand jurors. We oozed ridicule for the whole rotten system.

To call attention to the government’s witch-hunt, Judy and Sandy were dressed as witches in black cloaks and black pointed hats. I came dressed in a head-to-toe gorilla costume wearing a t-shirt that said “King Cong,” because the feds were looking for urban gorillas . (I rode a subway from the Upper West Side in the attire.) Walter was vintage Teague—your everyday working-class commie in blue work shirt festooned with National Liberation Front support buttons. Stew stole the show, showing up, as I wrote in a 2006 Counterpunch tribute, “as a cross-dressing female terrorist bombshell, glamming to the nines in an utterly f-a-b-u-u-u-u-l-o-u-s rainbow-striped minidress with the name ‘Bernardine’ stitched in sequins across the bodice.” (Note: Gumbo quoted my description in Yippie Girl, but attributed my words to a nameless “journalist friend.”)

Sadly Judy’s version of the story completely missed the joyful message of collaboration and resistance. She eschewed the story of shooting our collective finger in the face of government intimidation in order to frame a story celebrating her own heroic smackdown of authority. In doing so, she embraced the male model of shameless self-promotion that she rails against throughout the book.

According to Yippie Girl mythos, Judy says she was the only one of us five to called into the hearing chamber and tells a very anti-climactic (and untrue) story of the experience. As I recollect, Walter, the only one of us who didn’t look like he just stepped out of a cartoon or the funny farm, was the only person summoned to the jury. (A federal marshal informed me that I would have to remove my gorilla suit when I was called. “Okay,“ I said, adding that it was a very hot day and “I wasn’t wearing anything underneath.”)

We all had been well-prepared by our crack legal team headed by Bill Schaap and Lennie Weinglass, and Walter’s appearance lasted less than five minutes. Guy Goodwin opted not to call in the rest of the crazies—it seems a lot of at-risk old people with weak hearts volunteer for grand juries, and he didn’t want to risk an EMS call.

Thus the New York grand jury inquisition came to a fizzling climax, and we Yippies and fellow travelers provided a template for our sisters and brothers facing the same government overreach in other jurisdictions across the country. Authoritarian repression was lampooned to death on its own doorstep.

Judy missed the opportunity to mythologize to our collaborative victory, and this, I think, is the low point of the book.

Before I go further, I cannot ignore the fact that I was born with standard male genitalia and use male pronouns and now am attempting to critique—some of you may say, mansplain—a woman’s story about her struggle to be heard above the din of male voices. I will do my best.

Starting at home in Toronto, Gumbo witnessed the effects of patriarchy as her father confidently promoted public relations for the Soviet regime and her mother angrily disappeared into a bottle. Judy didn’t suspect marital infidelity by her father, but fucking around quickly became a factor in her own life after she opened her bedroom door and found her first husband with another woman.

As she became acquainted with the female half of some of the Sixties most prominent “movement power couples,” Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver, Anita and Abbie Hoffman, Nancy Kurshan and Jerry Rubin—and herself became half of one such power pairing with Stew Albert—she began to discover how poisonous gender inequality can cause distrust among women and cause them to doubt their own minds.

On getting a cold shoulder in her first meeting with Anita Hoffman, Judy writes that she later “understood that Anita’s unfriendliness was not about me—Anita was suspicious of any stranger who happened to be a woman… She faced the traditional, patriarchal bind of a woman married to a charismatic man.”

“Only after the rise of the women’s movement,” Gumbo adds, “did Anita and I become friends.”

To borrow Greek mythology again, Tiresias was the ancient Theban seer who spent seven years as a woman so they could settle an argument between Zeus and Hera about whether men or women enjoyed sex more.

I am no Tiresias, and I am a much older and more testosterone-challenged human than when I waged dada-inspired mindfuck warfare alongside Judy and Stew and the entire Yippie gang in NYC. Call my next remarks mansplaining for men if you will, but I now am gonna tell the brothers why Yippie Girl, in spite of its blemishes, is an important book to read.

If I have learned one thing during a lifetime struggle to both cause change and then embrace it, even when it becomes a little uncomfortable, it is that avoidance of the conversation only breeds hostility and is anathema to change.

For men to become mindful partners in the struggle for social and economic justice, we must open our minds and begin to understand that male privilege, like white privilege and class privilege, is the ravager of egalitarian society.

While Judy Gumbo presents her quest for gender equality as a work in progress, relatively free of what many men misperceive as feminism’s automatic guilty verdict against manhood, she aims to steer her story away from negativity and reproach—except for the drunken Revolutionary Union (RU) cretin [my description] who tried to rape her in Berkeley. She also calls herself out when needed.

Judy’s journey is one of searching for her own better self amidst the detritus of patriarchal leadership norms, and when she succeeds and when she falls short—and I suggest instances of both in my remarks above—her successes and failures have much to offer as men—and women—grapple with the corpulent burden of culture. Men are afflicted with always being right, even when we’re wrong. Women struggle to create a narrative of inclusivity but are sometimes unwittingly lured into easy answers about right and wrong. We as a species are a work in progress.

As the archetypal Yippie Girl, Judy Gumbo still grapples up toward the mountaintop where the boy gods meet and make the rules.

[James Retherford is an Austin-based writer, graphic designer, and political activist, and an occasional contributor to The Rag Blog. Jim, who was active in SDS, the Yippies, and political guerrilla theater, was a founder and editor of underground newspaper The Spectator in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1966, and was the ghost writer for Jerry Rubin’s iconic book, Do It!]