How Nigeria’s Igbo highlife music provided hope after a devastating civil war

An Igbo young man playing the Abia (drum). Image from Ou Travel and Tour, used with permission

Read the first part of this series on the pioneers of Igbo highlife music here.

Igbo highlife provided comfort and hope for the Igbos, an ethnic group living mainly in southeastern Nigeria, after a devastating civil war that ended in 1970. In face of this agony, highlife musicians brought solace by encapsulating the trials of their times with a call to trudge on, despite the prevailing difficulties. Through the 80s and 90s, Igbo highlife continued to evoke the peculiar mood of the times.

The Nigerian civil war broke out after the 1966 failed coup tried to overthrow a northern head of state, which was led by Igbo officers. The backlash from the coup ignited a massacre of Igbos and other southerners living in northern Nigeria. The violence immediately afterward resulted in “deaths ranging as high as 30,000” forcing “more than 1 million” Igbos to flee back to “the Eastern Region,” according to a study by Helen Chapin Metz, a researcher with the American Library of Congress. The Igbos reacted with secession from Nigeria, creating the Republic of Biafra. This culminated in the 1967-1970 Nigeria/Biafra civil war that resulted in the death of “over one million ethnic Igbos and other Easterners,” asserts Chima J. Korieh, a professor of African History at United State’s Marquette University.

Post-civil war Igbo highlife music

The civil war sent more than a million Igbos, scattered around Nigeria, back home to the eastern region. This entrenched highlife in the east, asserts Oghenemudiakevwe Igbi, a Nigerian scholar. The lyrics code-switching from Igbo to English language made the highlife genre “an acculturative product of the folk music” of the Igbo culture, from where it blossomed, asserts Ikenna Onwuegbunna, a Nigerian music scholar.

After the Nigerian civil war from 1967 to 1970, the Igbos were totally devastated, having lost their lives and livelihood. The official “no victor, no vanquished” post-civil war mantra, captured the government’s commitment of the reintegration of Biafrans into the Nigerian state. However, the harsh reality was that the same Nigerian government directed that “£20 be paid to all Biafran bank account holders, regardless of the balance of their accounts prior to” the war. This broke survivors of the debilitating war, perhaps even more than the actual conflict.

Igbo highlife music, as personified by the Oriental Brothers International Band, offered a ray of light, amidst this grim reality.

The Oriental Brothers International Band

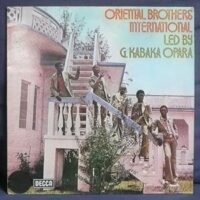

Original Nigerian vinyl (Afrodesia label) of the Oriental Brothers International (1976).

The Opara brothers, Godwin Kabaka Opara, Ferdinand (Dan-Satch) Emeka Opara, Christogonous Ezebuiro “Warrior” Obinna, and Kabaka Opara, along with Nathaniel “Mangala” Ejiogu, Hybrilious Dkwilla’ Alaraibe, and Prince Ichita, founded the Oriental Brothers in 1972. By the end of the decade, the group had released 20 albums.

One of Nigeria’s most successful bands, the Oriental Brothers played a pivotal “spiritual role” in keeping the Igbos “sane,” after the trauma inflicted by a “war so vicious,” according to All Music, a global music database.

Unfortunately, the band broke up with Kabaka leaving in 1977 to form the Kabaka International Guitar Band, following a leadership squabble with Dan-Satch. Three years later, Warrior also went solo, forming Dr. Sir Warrior and The Original Oriental Brothers. Years later, the group reunited to record two albums: “Anyi Abiala Ozo” (1987) and “Oriental Ge Ebi” (1996).

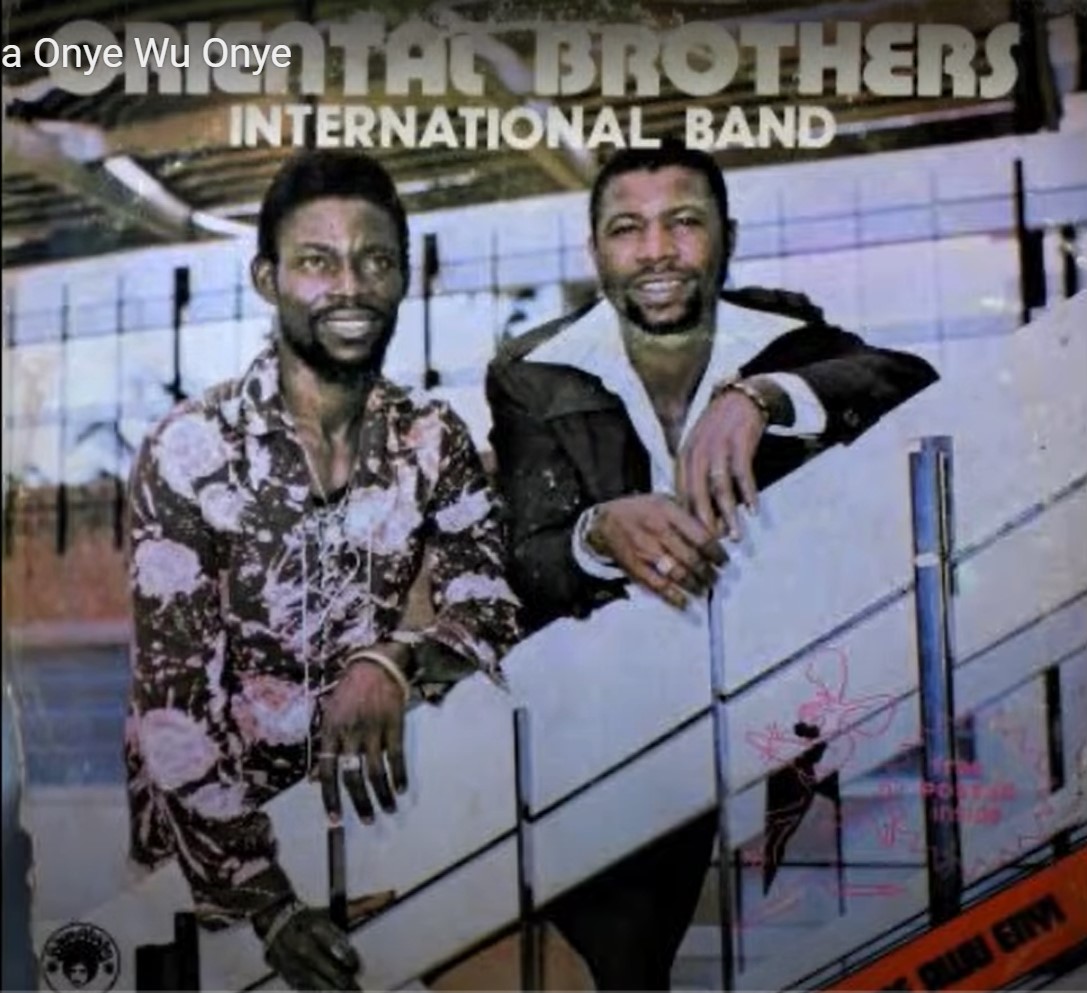

L:R: Dan-Satch and Warrior, Oriental Brothers Album Cover

In March 2015, Dan-Satch Opara gave some insights to the inspiration behind some of the songs by the Oriental Band Brothers, during an interview with the Nitch, a Nigerian entertainment online newspaper. For instance, ‘Ihe chi nyere m, onye a nana m’ is a literal translation of the Igbo philosophical aphorism, “that no one should snatch what God has given me (or someone else).” ‘Ebele onye uwa’, Dan-Satch continues, was a “premonition of the split of Oriental Brothers.”

Another song, ‘Iheoma’ was about the Udoji award of 1975. In 1972, Chief Jerome Udoji, was the head of the commission that was tasked by the government to reform Nigeria’s postcolonial and post-war civil service. The enhanced salary structure for civil servants proposed by the commission was subsequently known as the “Udoji Award.” Therefore, ‘Iheoma’ ridiculed the non-inclusion musicians in the enlarged pay packet. Dan-Scotch explains, “some people got so much money and bought motorcycles or cars. Nothing was given to us musicians then […] despite our contributions to the happiness of the people.”

The band stood out for their unique blending of Congolese guitar instrumentation with traditional Igbo rhythms. Their soulful and therapeutic musical renditions ruled the radio waves down into the 80s. The Oriental Brothers stressed the need for peaceful and harmonious living. Most of “their song themes were drawn from war experiences diluted with rich Igbo proverbs,” maintains Amaka Obioji, a journalist with Legit, a Nigerian online news site.

Ozoemena Nsugbe’s egwu ekpili

The Igbo traditional egwu ekpili musical instruments. L-R: Ichaka, ubọ aka, Ichaka and ọkpọkọrọ (also called ekwe nta or ekwe aka). Image by Giovana Fleck/Global Voices.

Egwu ekpili is a genre of traditional Igbo music predominant among Igbos from Ọnịcha, Nsugbe, Nteje, Aguleri, in Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria, is characterised by the call and response repertoire. This Igbo folk music “deploys conventional and conceptual metaphors to articulate salient Igbo identities and ideologies,” notes Ebuka Elias Igwebuike, a Nigerian language and literary scholar. The ọkpọkọrọ (also called ekwe nta or ekwe aka), ịchaka and ubọ aka – egwu ekpili musical instruments – dates back to about 950 AD in traditional Igbo societies.

Akunwata Ozoemena Nsugbe's album cover.

This genre has been integrated into Igbo highlife music, with the electric guitar and piano featuring prominently, alongside the traditional ekpili Igbo instrumentation. Akunwata Ozoemena Nsugbe who started singing in 1967, and Chief Emeka Morocco Maduka, popularly known as ‘Eze Egwu Ekpili,’ are some of the notable egwu ekpili highlife crooners. The themes of their songs were mostly philosophical and moralistic.

Zigma sound, a fusion of highlife, folk song and vocals

Bright Chimezie’s album cover

Bright Chimezie promoted a mix of Igbo traditional music, highlife, and vocal through his Zigima Sound which was popular in the early 80s. The gap-toothed Chimezie, labeled Okoro Junior by fans, held the Nigerian music scene spellbound with his impressive leg work in numerous live performances.

Nigerian journalist, the late Amadi Ogbonna wrote of Chimezie:

His breathtaking performance on stage also endeared him to the crowd wherever he performed. A very creative musician, Bright Chimezie was able to infuse comedy into his songs. Songs like ‘Respect Africa,’ ‘Okro Soup’ and ‘Oyibo Mentality’ propelled him to national stardom.

Chimezie, a strong believer “in African culture and traditions” asserts in a 2010 interview that he used music to creatively tell stories. “The message I am trying to get across to the people there is that we should be very proud of where we come from. The kind of food we eat, our type of dresses,” Chimezie said.

These highlife musicians drawing their inspirations from Igbo identity went deep in their interrogation of existential questions while offering entertainment to their fans. Chimezie maintains that there was “a philosophy” in their music, evident in “the lyrical context” that told the story of the people. The fusion of Western and Igbo musical instruments also gave their songs a popular validity that is still refreshingly unique.

Here's a playlist of Igbo highlife music from the 70s to the 90s: