“Forbidden Loves and Secret Lusts”: Rose Library hosts exhibition featuring queer pulp fiction

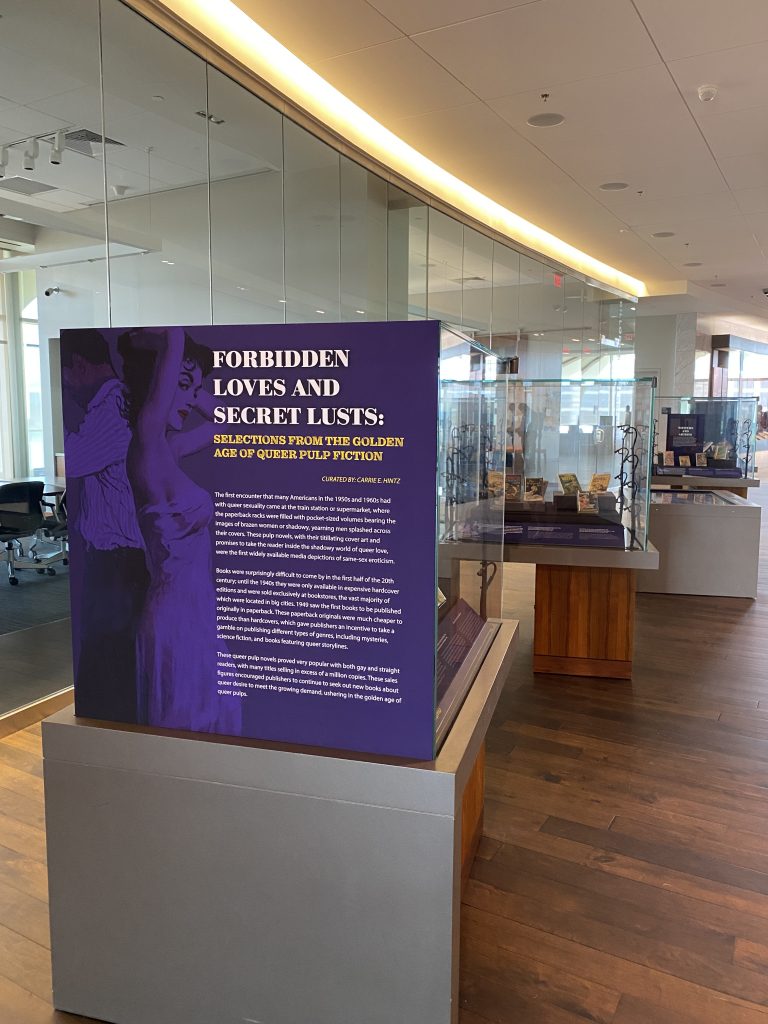

In celebration of Pride month, Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library is showcasing queer pulp fiction books in an exhibition called “Forbidden Loves and Secret Lusts: Selections from the Golden Age of Queer Pulp Fiction.”

The exhibit, which includes about 30 rare books about lesbian and gay relationships — as well as images of accompanying artifacts like cover art and movie posters — is located on the 10th floor of the Robert W. Woodruff Library.

“Forbidden Loves and Secret Lusts” will be available until Oct. 7, the first day of the Atlanta Pride festival. The Rose Library will host its second annual drag show at 7:00 p.m. on Oct. 5 in the Woodruff Library’s Jones Room to close out the exhibit, according to Rose Library Associate Director Carrie Hintz.

“We are holding it … so it can kind of bridge both of those pride moments,” Hintz said.

Photo courtesy of Carrie Hintz

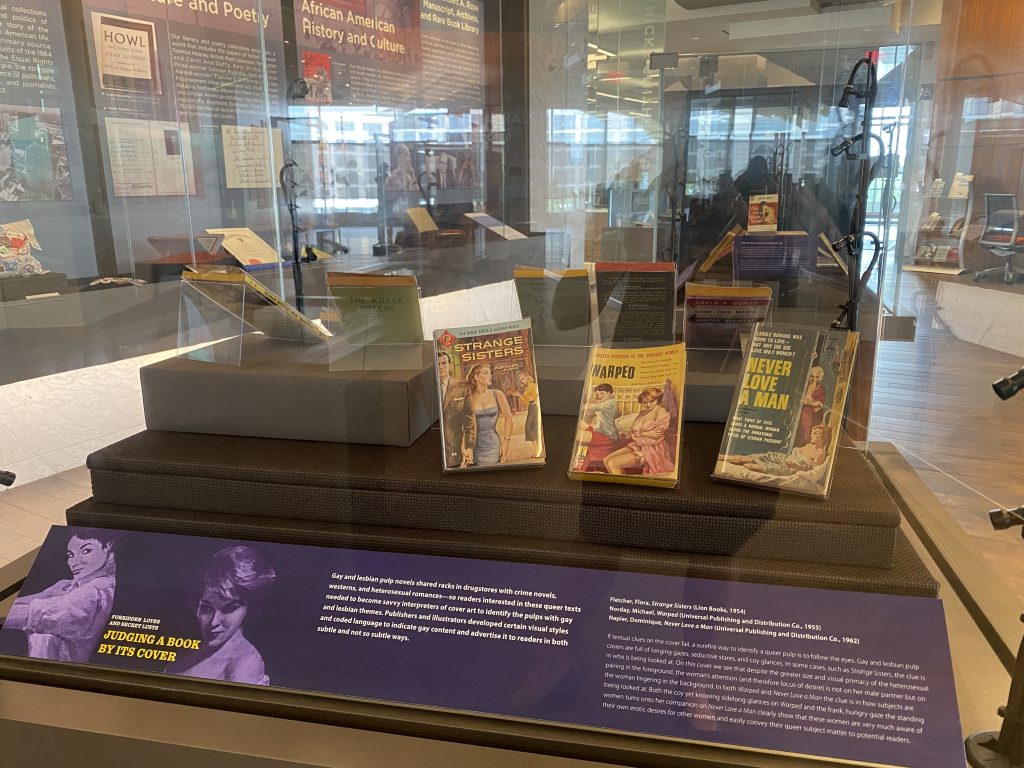

The displayed pulp fiction books — which are cheap, mass-produced works of fiction often about sensational subjects — are primarily from the 1950s through the mid-1960s, and include the lesbian novels “The Price of Salt” by Patricia Highsmith, “I am a Woman” by Ann Bannon and “Never Love a Man” by Dominique Napier. There are several books featuring gay men, including spy thrillers and cowboy stories, which were popular genres at the time.

Hintz said some nonfiction pieces, which are “billed as inside the secret lives of gay men and lesbians,” are also included.

The queer pulp fiction exhibit is Hintz’s brain child. She wrote her master’s thesis on lesbian pulp fiction novels and helped establish “Forbidden Loves and Secret Lusts” as the first full exhibit dedicated to queer pulp fiction at Emory.

“It’s an idea that I’ve had in my head for a while now, seeing the collections that we have and knowing what kind of stories I could tell with these books,” Hintz said.

Emory has been collecting original copies of queer pulp fiction for years, but recently bought and borrowed reprints of some of the novels, which were made by feminist presses in the 1980s and early 2000s, Hintz added.

“We have always focused on queer pulp collections on the original books from the 1950s and 1960s, but I also wanted to show the ways that these novels, at least some of them, had lives beyond that period of history,” Hintz wrote.

Most of the books were published in the “golden age” of queer pulp fiction, Hintz noted. Books were expensive in the 1940s, as they were often only available as hardcovers at book stores in major cities. However, literature became more accessible in the 1950s with the rise of mass-produced pulp fiction — the small, cheap fiction books were sold in lunch counters, drug stores and cigar shops.

There are accounts, Hintz explained, of queer women finding these books on racks at the drugstore and realizing for the first time that other lesbians exist and the feelings they had were normal.

“They weren’t completely isolated,” Hintz said. “For a lot of people, these books were really extremely important forms of representation and the first time that they’ve ever seen queer desire represented at all in their lives.”

Photo courtesy of Carrie Hintz

However, the books were published amid government censorship. United States obscenity laws, which still exist today, prohibit the distribution of “obscene matter,” including inappropriate language and representations of sexual abuse. At the time the queer pulp fiction books were written, homosexuality was often considered obscene, so a book ending with a happy lesbian or gay relationship would be “condoning an immoral lifestyle, Hintz explained.

To avoid appearing as if the authors support homosexuality, the stories often ended in tragedy — lovers died, converted back to heterosexuality or were institutionalized to allow publishers to produce a more “moralistic” book, Hintz explained. These endings often acted as a warning to readers by telling them what could happen if they engaged in same sex relationships.

“Some of the books are sympathetic or were written by queer people, but many more were trashy, sensation novels that didn’t even attempt to depict real queer people and their lives, loves and desires,” Hintz wrote. “There were certainly just as many dehumanizing or harmful depictions in these books as there were positive and sympathetic ones, and the conversion plots are very common and particularly pernicious and isolating for readers.”

But the books’ endings did not deter LGBTQ people from reading them. Queer pulp fiction, especially those depicting lesbian relationships, skyrocketed in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, both for the representation they gave to closeted readers and for the connections they fostered in the real world.

“If someone’s showing someone a particular title, it could be a way of saying, kind of flagging, ‘This is who I am, are you like this too?’” Hintz said. “It was such a key way for people to understand themselves, understand the world and understand a different way that they could fit into it than they may have without these novels and without these books.”

The Rose Library’s drag show will feature entertainers from Atlanta and across the South, according to Hintz. It is separate from the Student Programming Council’s October drag show, which features student performers.

Hintz wrote in a June 21 email to the Wheel that the Rose Library decided to host the drag show to “celebrate our rich holdings” that document LGBTQ history, culture, politics and activism. Drag history is included in “Forbidden Loves and Secret Lusts,” which showcases materials such as recordings of ‘The American Music Show,’ the local cable program where Drag Queen RuPaul Andre Charles kickstarted his career.

“The choice to do a drag show originated in the Rose Library’s desire to highlight the ways our collections connect to living cultures and subcultures that our students, guests, researchers, faculty and staff can participate in,” Hintz wrote. “As far we know, the Rose Library was the first academic research library in the country to host a drag show.”