BBC News, Daallo Mountain

The three kings of the biblical nativity carried three precious gifts to mark the birth of Jesus - but a modern-day gold rush in Somaliland is putting the ancient perfume trade in frankincense and myrrh at risk.

"The gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the three wise men to baby Jesus definitely came from here," said the old man sitting in the dust under a tree.

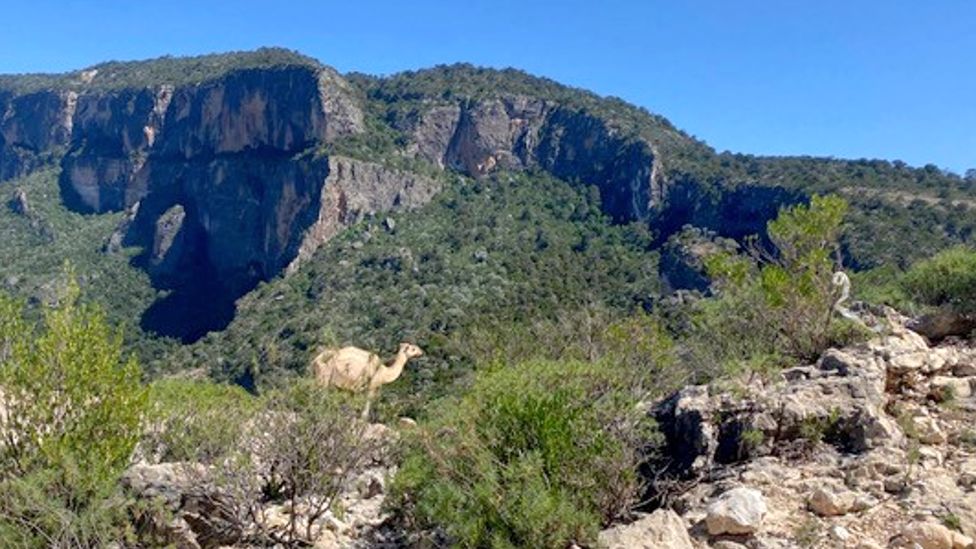

I met Aden Hassan Salah on Daallo Mountain, part of the Golis range that straddles the self-declared republic of Somaliland and Puntland State in Somalia. Both territories claim the area.

"The routes of the camel caravans that for centuries transported them from here to the Middle East can be seen from space," he said.

The Bible refers to how these animals carried the gifts to Bethlehem where it is believed that Jesus was born.

A younger man, dressed in a sarong and Manchester United football top, sprang up from the ground. His name was Mohamed Said Awid Arale.

Many of the gold-diggers who started arriving in Daallo Mountain in 2017 are former nomads

"As I'm sure you know, 'Puntland' means the 'land of exquisite aromas,'" he said.

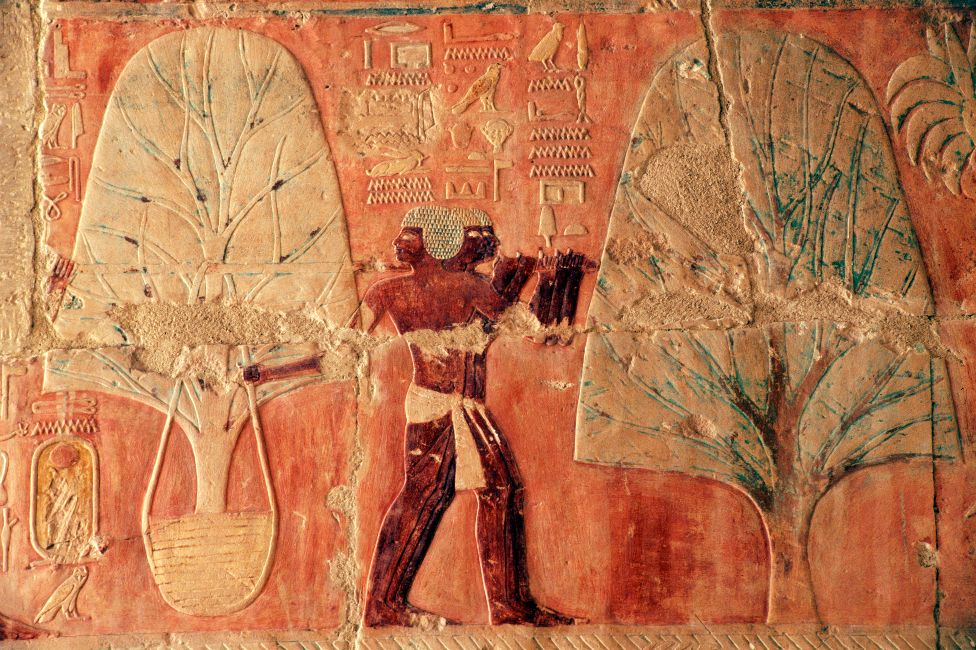

"One thousand, five hundred years before Jesus was born, Egypt's most powerful female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, made a famous expedition here. She ordered the construction of five boats for the journey, filled them with the three precious substances, and sailed back home.

"Gold was used to adorn Hatshepsut's body, frankincense was burned in her temples and myrrh was used to mummify her after she died."

Gold, frankincense and myrrh have been exported from the region for thousands of years. Much of the world's frankincense comes from the Horn of Africa.

Today, one of the gifts brought to baby Jesus, gold, is sowing the seeds of destruction of the other two.

The men on Daallo Mountain are part of the problem.

The famous trees of this region of the Horn of Africa are depicted on the walls of the Temple of Hatshepsut

They spearheaded a gold rush which began around five years ago and has led to the uprooting of frankincense and myrrh trees, some centuries old.

"Gold-miners have swarmed into the mountains," says Hassan Ali Dirie who works for the Candlelight environmental organisation.

"They cut down all the plants when they clear areas for mining. They damage the roots of the trees when they dig for gold. They block crucial waterways with their plastic bottles and other rubbish," he said.

"Day by day, they are ensuring the slow death of these ancient trees. The first to go are the myrrh trees, which are uprooted when the diggers clear the land for surface mining.

"Frankincense trees last a bit longer as they grow on rocks and are destroyed once the miners dig deep into the earth."

Woody perfume

A little further up the hill is a frankincense village where the trees have been passed down from generation to generation.

A woman sat on a turquoise plastic chair in her porch surrounded by children, their mothers and baby goats.

We burn frankincense to chase away flies and mosquitoes. We inhale it to clear colds and we consume it to cure inflammation"Racwi Mohamed Mahamud

Owner of frankincense trees

"I have no idea what you're talking about," said Racwi Mohamed Mahamud when I asked her about the story of the Magi bearing gifts.

"All I know is that my family has owned these trees for hundreds of years. They are passed from great-great-grandfather to great-grandfather to grandfather to father to son."

She ordered a young man to fetch some frankincense recently tapped from a tree. He came out carrying a cloth bundle, set it on the ground and opened it. The air was filled with a delicious woody perfume.

We sifted through the sticky substance to find nuggets of frankincense. These are cleaned, dried and graded before being sold to middlemen who export them across the world to burn in churches, mosques and synagogues and to create medicine, essential oils, expensive cosmetics and fine perfumes, including Chanel No 5.

Ms Mahamud looked at me blankly when I asked her what she thought about her frankincense eventually ending up in fancy department stores promising miracle anti-ageing properties and mysterious, seductive aromas.

"That sounds like nonsense to me," she said.

"We burn frankincense to chase away flies and mosquitoes. We inhale it to clear colds and we consume it to cure inflammation. That's it."

This frankincense tree has been over-harvested

The tappers and graders get very little of the money made from frankincense, with a kilogram selling for between $5 (£4.15) and $9. There have been scandals involving ruthless middlemen and greedy foreign companies.

They get slightly more for myrrh which currently sells for $10/kg. Like frankincense, it is a resin tapped from small, thorny trees. It is used to embalm dead bodies and to make perfume, incense and medicine.

It is believed to have antiseptic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory qualities and is used in toothpaste, mouthwash and skin salves.

The villagers explain how the goldminers came to their area with their shovels and pickaxes.

"We stood firm against them," says Ms Mahamud shaking her fist.

"We said: 'You have come here for your crude, yellow gold. We have our green gold and nobody can take it away from us.'"

Frankincense resin, used in perfumes like Chanel No 5, fetches between $5 and $9 pr kg

The miners ran away and never came back.

The atmosphere in the frankincense village was completely different from that in the goldminers' settlement.

It was basic, but there was a sense of community.

People young and old strolled about, chatting, drinking tea and complaining about how low frankincense prices made it difficult to make ends meet, especially during this time of high inflation and severe drought.

Drugs and jihadist taxes

It took a while to work out what was so strange about the goldminers' place.

Eventually I realised there were no women or children there.

"We don't really know what has happened to our families," said Mr Salah, the old man I met sitting under the tree.

"We used to be nomads but endless failed rainy seasons and droughts meant we had to give up our traditional way of life."

He explained how they came to the mountains in 2017 to look for gold.

"There was nothng here when we arrived. It was just a dry river bed. This was the first place where gold was found. We have built it up into a kind of village," he said pointing at some shacks built from sticks.

I asked Mr Salah and the few dozen other men sitting with him whether they preferred the gold-digger's life to that of a nomad. They shook their heads and shouted out in rage.

"As nomads we had dignity. We depended on nobody. We lived with our families, our camels, goats and sheep. We lacked for nothing," he said.

"The camels carried our shelters and cooking pots. The livestock provided our food and milk. We cannot eat or drink the gold we find. It cannot carry our shelters and belongings."

The miners explained how they sold the mineral to traders who smuggled it by sea to Dubai.

Gold-mining is not only destroying the environment. It is wrecking their lives.

"We have become drug addicts," said Mr Arale, the man in the red Manchester United shirt

"We are hostages to khat dealers," he said, referring to a narcotic leaf chewed by many Somalis.

"They control our lives. We spend all our money on khat instead of our families, which are lost to us."

As they spoke, a land cruiser drove into the village. Two well-dressed men emerged from the vehicle. The miners said they were the khat dealers.

"Gold has ruined our lives in other ways too," said Mr Salah. "It has driven some of us mad, like our friend who found $50,000 worth of gold and lost his mind."

Candlelight's Mr Dirie explained how gold was destroying the local community.

"Some schools have closed because all the teachers have left to join the gold rush. Students are leaving too."

He said Somalis from other regions were coming into the mountains leading to deadly clan clashes.

"Many of the miners are armed," he said. "We must turn around and leave now. It is not safe to stay here for a long time."

The Islamist groups, al-Shabab and the Somali branch of Islamic State, have started to demand taxes from the gold-diggers.

As we drove out of the mountains on the long dusty road, I wondered if those who buy expensive perfumes, cosmetics and jewellery have any idea where the substances used to make them come from, how many hands they pass through and how much destruction they have caused.