At least 300 people have been arrested in Brazil after thousands of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro's supporters stormed Congress, the Supreme Court and presidential palace, then trashed the nation's highest seats of power.

Lucia Binding

News reporter

Monday 9 January 2023

Rioters have invaded and ransacked Brazil's Congress, presidential palace and Supreme Court - in a grim echo of the US Capitol riots two years ago by fans of former President Donald Trump.

The uprising, which lasted just over three hours, marked the severe polarisation that still grips the country.

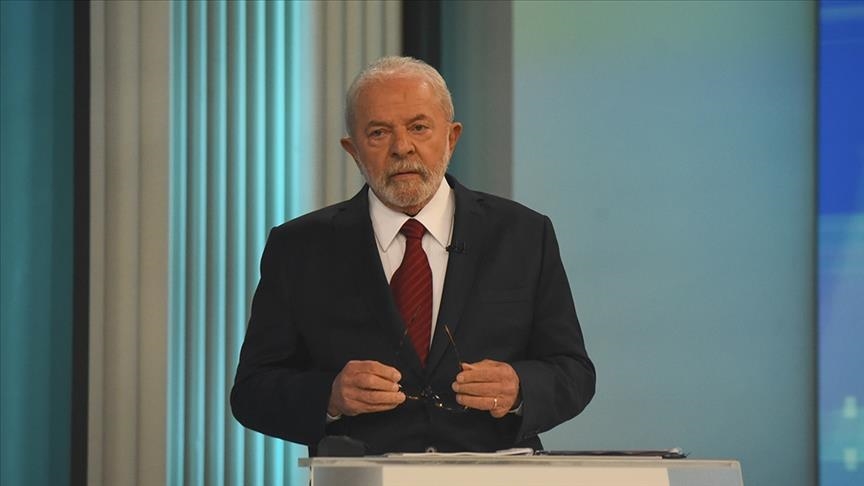

It came days after the inauguration of leftist President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who defeated Jair Bolsonaro in the October election in one of the tightest presidential races, with just 50.9% of the votes.

It also made Mr Bolsonaro the first president of Brazil to lose his bid for re-election.

The current Brazilian president, known as Lula, described the vandals on Sunday as "fanatical fascists" who "did what has never been done in the history of this country".

Speaking at a news conference during an official trip to Sao Paulo state, he added: "All these people who did this will be found and they will be punished."

Who is protesting - and why are they protesting?

The protesters are far-right supporters of Mr Bolsonaro, who disputed the election win of Lula on 30 October 2022.

Lula was previously president of Brazil from 2003 to 2011, but narrowly beat Mr Bolsonaro last year in a run-off vote.

Shortly after the election result, Mr Bolsonaro's supporters began gathering for the first time outside military bases across Brazil, calling for a military intervention to prevent Lula from returning to office.

In the following days, truckers were among Mr Bolsonaro's supporters who blocked roads throughout the country after his defeat.

In November, Mr Bolsonaro's supporters held rallies across the country, asking for an armed force intervention.

Brazilians flocked outside a regional military facility to denounce what they described as an unfair or stolen election, while defying a recent Supreme Court order to free-up roads and public spaces.

Many protesters were anticipating that a report by the Ministry of Defence, which Mr Bolsonaro has sought to involve in election oversight, would substantiate their claims.

The document, published in November, proposed improvements to address some flaws in Brazil's electoral systems, but it did not find any evidence of fraud.

Domingues Carvalho, 63, who protested for 15 days straight, told the AP news agency: "I'm fighting for my country, for my daughter and three grandchildren."

He added that he sometimes kneels down in front of the military building to pray. "I'll stay here as long as necessary. We are peaceful but we will never, ever leave our country in the hands of communists," he said.

What has fuelled the rallies?

On 22 November, Mr Bolsonaro challenged the results of the Brazilian election and argued that votes from some machines should be "invalidated" in a complaint that was later rebuffed by election authorities.

Although the Bolsonaro administration has not directly opposed the transition of power, the far-right leader has yet to concede or congratulate his opponent.

His supporters have taken the cue - and are also refusing to accept the result.

"This election was not fair," said 51-year-old entrepreneur Anselmo do Nascimento. "The Supreme Court should be neutral."

In December, Lula's election victory was certified by the federal electoral court.

Later that day, Mr Bolsonaro's supporters attempted to invade the federal police headquarters in Brasilia, the capital, which was prompted by the arrest of a pro-Bolsonaro indigenous leader for alleged anti-democratic acts.

Protesters have also condemned the shutting down of many pro-Bolsonaro accounts and groups on social media platforms - describing it as akin to censorship.

Build up to 8 January riots

On Christmas Eve, a man identified as George Washington de Oliveira Sousa was arrested for attempting to set off a bomb in protest against Brazil's election results. A copy of his police statement showed he was inspired to build up an arsenal by Mr Bolsonaro's traditional support of the arming of civilians.

And on 29 December, Brazilian police arrested at least four people over an alleged coup attempt during riots by Mr Bolsonaro's supporters.

Lula was sworn in as president for the first time on 1 January, where he said democracy was the true winner of the presidential election - but he takes the reins of a polarised Brazil.

Lula sworn in as Brazil's president

It wasn't always like that, however. When he retired in 2011 it was with 83% approval ratings. A series of scandals led to his imprisonment on corruption charges which were subsequently annulled.

This was the final event before the storming of the Brasilia Capitol on 8 January by Mr Bolsonaro's supporters.

How Trump's allies stoked Brazil Congress attack

The scenes in Brasilia looked eerily similar to events at the US Capitol on 6 January two years ago - and there are deeper connections as well.

"The whole thing smells," said a guest on Steve Bannon's podcast, one day after the first round of voting in the Brazilian election in October last year.

The race was heading towards a run-off and the final result was not even close to being known. Yet Mr Bannon, as he had been doing for weeks, spread baseless rumours about election fraud.

Across several episodes of his podcast and in social media posts, he and his guests stoked up allegations of a "stolen election" and shadowy forces. He promoted the hashtag #BrazilianSpring, and continued to encourage opposition even after Mr Bolsonaro himself appeared to accept the results.

Mr Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, was just one of several key allies of Donald Trump who followed the same strategy used to cast doubt on the results of the 2020 US presidential election.

And like what happened in Washington on 6 January 2021, those false reports and unproven rumours helped fuel a mob that smashed windows and stormed government buildings in an attempt to further their cause.

'Do whatever is necessary!'

The day before the Capitol riot, Mr Bannon told his podcast listeners: "All hell is going to break loose tomorrow." He has been sentenced to four months in prison for refusing to comply with an order to testify in front of a Congressional committee that investigated the attack but is free pending an appeal.

Along with other prominent Trump advisers who spread fraud rumours, Mr Bannon was unrepentant on Sunday, even as footage emerged of widespread destruction in Brazil.

"Lula stole the Election… Brazilians know this," he wrote repeatedly on the social media site Gettr. He called the people who stormed the buildings "Freedom Fighters".

Ali Alexander, a fringe activist who emerged after the 2020 election as one of the leaders of the pro-Trump "Stop the Steal" movement, encouraged the crowds, writing "Do whatever is necessary!" and claiming to have contacts inside the country.

Bolsonaro supporters railed online about an existential crisis and a supposed "communist takeover" - exactly the same type of rhetoric that drove the rioters in Washington two years ago.

Casting doubt on voting systems

The links between Mr Bolsonaro and the Trump movement were highlighted by a meeting in November between the former president and Mr Bolsonaro's son at Mr Trump's Florida resort.

During that trip, Eduardo Bolsonaro also spoke to Mr Bannon and Trump adviser Jason Miller, according to reports in the Washington Post and other news outlets.

As in the US in 2020, partisan election-deniers focused their attention on the mechanisms of voting. In Brazil, they cast suspicion on electronic vote tabulation machines.

A banner displayed by the rioters on Sunday declared "We want the source code" in both English and Portuguese - a reference to rumours that electronic voting machines were somehow programmed or hacked in order to foil Mr Bolsonaro.

A number of prominent Brazilian Twitter accounts which spread election denial rumours were reinstated after the election and acquisition of the company by Elon Musk, according to a BBC analysis. The accounts had previously been banned.

Mr Musk himself has suggested some of Twitter's own employees in Brazil were "strongly politically biased" without giving details or evidence.

Some of Mr Trump's opponents in the US were quick to put the blame on the former president and his advisers for encouraging the unrest in Brazil.

Jamie Raskin, a Democratic Party member of the US House of Representatives and a member of the committee that investigated the Capitol riot, called the Brazilian protesters "fascists modeling themselves after Trump's Jan. 6 rioters" in a tweet.

The BBC attempted to contact Mr Bannon and Mr Alexander for comment.

With reporting from the BBC's disinformation team

Terrence McCoy

Latin America's largest country embarked on what amounted to a test of its democratic strength in 2018 when it elected the former army captain who openly lamented the collapse of the country's military dictatorship, once threatened to reinstall its rule on the first day of his presidency and sought at every turn to sow doubt in elections.

During his time in office, he did little to soften his bellicosity. He warned of a government "rupture" like the military coup of 1964. If he were to lose his re-election bid, he said, it could only be through fraud, and Brazil would "have worse problems" than the United States did on January 6, 2021, when a mob of Donald Trump supporters assaulted the US Capitol.

His son Eduardo, a federal congressman, once warned that "there will arrive a moment when the situation will be the same as it was in the 1960s."

For many Brazilians, Sunday afternoon (local time) was the arrival of such a moment, when Bolsonaro supporters laid siege to the three pillars of the federal government - the presidential palace, the supreme court and the congress - bringing democracy here to a sudden standstill. The scenes of smoke and violence were at once both shocking and predictable, the tragic realisation of a prophecy Bolsonaro has repeatedly uttered to mobilise his base and terrify his adversaries.

If I'm removed from power, he often hinted, violence will follow.

ERALDO PERES/AP

Protesters, supporters of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro, storm the National Congress building in Brasilia, Brazil, on Sunday (Monday NZT).

"Bolsonaro and the Bolsonaro family have for years talked about attacking the supreme court," said Esther Solano, a sociologist at the Federal University of São Paulo who studies the president's supporters. "Then, over the last year, they have said they wouldn't respect the electoral results. And in recent months, the insurrectionist rhetoric of Bolsonaro and his family gathered even more force."

Bolsonaro has said little publicly since his loss to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in October. He declined to concede, or to discourage the supporters who have camped outside military installations calling for a coup to keep him in power.

He did ask protesters to stop disrupting commerce by blocking roads, and he condemned violence aimed at overturning the election result. But in an echo of Trump, he skipped Lula's inauguration on January 1, absconding instead to Florida to stay at the Orlando mansion of an MMA fighter.

In a teary farewell before his departure, he called the election result unfair. Now in his sudden absence, his most radical supporters have carried out his rhetoric to its logical, if violent, conclusion.

"This was expected," said Alexandre Bandeira, a political analyst in Brasília. "This was a ticking time bomb. Bolsonaro's supporters have decided to repeat the lamentable image for the entire world of the Capitol invasion."

Bolsonaro condemned the violence in Brasília on Sunday - and found a way to criticise his adversaries.

"Peaceful demonstrations, by law, are part of democracy," he tweeted, hours after the assault began. "However, depredations and invasions of public buildings as occurred today, as well as those practiced by the left in 2013 and 2017, were outside of the law."

From the earliest days of his presidency, he flirted with the most extreme members of his base - a segment of the population that sees such decrepitude in Brazilian society and political structures that it can only be cleansed with the blunt instrument of military force. They view the years of the military dictatorship, which tortured and killed opponents, as a golden era in Brazil - when society was free of corruption and crime.

They found a champion in Bolsonaro, who had hung photos of the regime's leaders in his congressional office and bemoaned the fact that it hadn't killed more people when it had the chance. After his rise to power, they repeatedly called on him to clear away all constraints on his authority and bring back military rule. He encouraged and inflamed their protests by attending them.

ERALDO PERES/AP

A protester, supporter of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro, launches a fire extinguisher during the riot.

As his administration accumulated problems - corruption, a crippling coronavirus outbreak that killed nearly 700,000 Brazilians, supreme court investigations into his closest allies - he repeatedly returned to the embrace of his fringe supporters. He threatened the other branches of government and conjured the spectre of military intervention if others threatened his grip on power.

"We have the people on our side, and the armed forces are on the side of the people," he said in March 2020.

And then, he set the stakes.

"The patience of the people has run out," he declared in September 2021. "I want to tell those who want to make me unelectable in Brazil: Only God removes me from power. There are three options for me: jail, death or victory. And I'm telling the scoundrels, I will never be imprisoned!"

ERALDO PERES/AP

A supporter of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro, in confronted by police after the demonstrators stormed the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, Brazil.

As the election neared, and with polls showing him badly trailing Lula, Bolsonaro again turned to violent rhetoric. He described the election as an epochal struggle between good and evil. He warned that malevolent forces were ready to steal the election from the Brazilian people. He said Lula would bring about the ruin of the country.

"There's a new type of thief, the ones who want to steal our liberty," Bolsonaro said in June. "If necessary, we will go to war."

Then, when the election was over and Lula declared the winner, the endlessly loquacious Bolsonaro did something surprising: He kept his mouth shut. He did little to contest the results of the elections. He made a brief appearance two days after the vote, acknowledging disappointment but declining to concede. His chief of staff then stepped forward to say the president had authorised him to oversee a transition.

ERALDO PERES/AP

Protesters, supporters of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro, attack a police armoured vehicle.

Bolsonaro then holed up inside the presidential palace for weeks, reportedly despondent over his loss, before leaving the country as Lula was set to take power.

In that silence, analysts say, the most radical members of Bolsonaro's base have gained a foothold. They closed down highways. They camped in front of military bases, calling on commanders to stage a coup to keep him in power.

In Brasília, they attacked a police station after the arrest of one of their members. One radicalised bolsonarista, named George Washington de Oliveira, was arrested and accused of planting an armed bomb beneath a bus at the Brasília airport. In a statement to police, he said he wanted to "begin chaos" that would lead to a military intervention.

ERALDO PERES/AP

Protesters seen storming the Planalto Palace building in Brasilia, Brazil.

Through it all, Bolsonaro was largely silent.

"His silence was terrible," said Jairo Nicolau, a political scientist at the research institute Fundação Getulio Vargas. "It signalled to a part of his followers that are more ideological that he is supporting them, that they are doing what their big boss can't do.

"His silence was the major spark that lit the protests that are now happening."

The Washington Post

Supporters of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro demonstrate against President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, outside Brazil’s National Congress in Brasilia, Brazil, January 8, 2023. (Reuters)

AFP, Washington

Published: 09 January ,2023: 08:51 AM GSTUpdated: 09 January ,2023: 08:55 AM GST

President Joe Biden assailed Sunday’s attacks by supporters of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil as “outrageous,” as condemnation poured in from around the world against mobs that smashed their way into the halls of power in Brasilia.

For all the latest headlines follow our Google News channel online or via the app.

That one word comment from Biden was his first direct public comment since crowds broke into Congress, the Supreme Court and the presidential palace in Brasilia to protest the far-right incumbent’s removal from power after losing his election against leftist challenger Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

As part of an outpouring of support for Lula after the stunning scenes in Brazil’s capital, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez assailed the “coup attempt” by supporters of Bolsonaro.

Fellow South American leaders in Chile, Colombia and Venezuela deplored the mob action, and French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted his support for Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the leftist who took office as Brazil’s leader a week ago.

“The will of the Brazilian people and the democratic institutions must be respected!” Macron tweeted.

US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan tweeted that Biden “is following the situation closely and our support for Brazil’s democratic institutions is unwavering.”

Brazil’s democracy, he added, “will not be shaken by violence.”

The European Union’s top foreign affairs official, Josep Borrell, tweeted that he was “appalled by the acts of violence and illegal occupation of Brasilia’s government quarter by violent extremists today...

“Brazilian democracy will prevail over violence and extremism,” he added.

The Twitter account of Democrats on the US Senate foreign relations committee noted that the Brasilia ransacking came nearly two years to the day after supporters of then-president Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol in an attempt to overturn the 2020 election, leaving five dead.

“Trump’s legacy continues to poison our hemisphere,” the tweet said.

Around the Western hemisphere, reaction was particularly swift from leaders ideologically akin to Lula.

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador tweeted: “Lula is not alone, he has the support of the progressive forces of his country, of Mexico, of the American continent and of the world.”

Chilean President Gabriel Boric decried “this cowardly and vile attack on democracy” and said the Lula government has Chile’s “complete backing.”

Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro, a leftist authoritarian, condemned what he called the “neofascist groups” seeking to unseat Lula.

More condemnation came in from across Latin America.

Cuba’s President Miguel Diaz-Canel offered solidarity and condemned what he described as anti-democratic acts aimed at “generating chaos and disrespecting the popular will.”

Bolivia’s foreign minister Rogelio Mayta said the events showed that Latin America faces a challenge of “defending our democracies by preventing the triumph of hate speech… fratricidal violence and anti-democratic actions.”

Read more: Pro-Bolsonaro rioters storm Brazil’s Congress, Supreme Court, Presidential Palace

The New Arab Staff & Agencies

09 January, 2023

In scenes reminiscent of the January 6, 2021 invasion of the US Capitol building by supporters of then-president Donald Trump, initially overwhelmed security forces used tear gas, stun grenades and water cannon to fight back rioters who ran rampage through the halls of power in Brasilia until they were finally subdued.

The far-right Bolsonaro meanwhile condemned "pillaging and invasions of public buildings" in a tweet. But the politician dubbed the "Tropical Trump" rejected Lula's claim he incited the attacks, and defended the right to "peaceful protests."

Lula, who was in the southeastern city of Araraquara visiting a region hit by severe floods, signed a decree declaring a federal intervention in Brasilia, giving his government special powers over the local police force to restore law and order in the capital.

"We will find out who these vandals are, and they will be brought down with the full force of the law."

The president then flew back to Brasilia to tour the ransacked buildings and oversee the response, Brazil's TV Globo reported.

Police have made 170 arrests, media reports said.

TV images showed police ushering Bolsonaro supporters down the ramp from the Planalto presidential palace in single file -- the same ramp Lula climbed a week earlier at his inauguration.

The Senate security service said it had arrested 30 people in the chamber.

The chaos came after a sea of protesters dressed in military-style camouflage and the green and yellow of the flag flooded into Brasilia's Three Powers Square, invading the floor of Congress, trashing the Supreme Court building and climbing the ramp to the Planalto.

Social media footage showed rioters breaking doors and windows to enter the Congress building, then streaming inside en masse, trashing lawmakers' offices and using the sloped speaker's dais on the Senate floor as a slide as they shouted insults directed at the absent lawmakers.

Protesters damaged artworks, historic objects and furniture and decorations as they ran riot through the buildings, according to Brazilian media reports.

One video showed a crowd outside pulling a policeman from his horse and beating him to the ground.

Police, who had established a security cordon around the square, fired tear gas in a bid to disperse the rioters -- initially to no avail.

A journalists' union said at least five reporters were attacked, including an AFP photographer who was beaten by protesters and had his equipment stolen.

Hardline Bolsonaro supporters have been protesting outside army bases calling for a military intervention to stop Lula from taking power since his election win.

Lula's government vowed to find and arrest those who planned and financed the attacks.

Brasilia Governor Ibaneis Rocha fired the capital's public security chief, Anderson Torres, who previously served as Bolsonaro's justice minister.

The attorney general's office said it had asked the Supreme Court to issue arrest warrants for Torres "and all other public officials responsible for acts and omissions" leading to the unrest.

It also asked the high court to authorize the use of "all public security forces" to take back federal buildings and disperse anti-government protests nationwide.

ByLia Timson

January 9, 2023 —

The copycat invasion of the Brazilian Congress, Supreme Court and Planalto Palace by backers of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro seeking to emulate the storming of the US Capitol is the culmination of a democratic downhill slope worldwide and not the people’s revolution it purports to be.

The parallels with the far-right movement ignited by former US president Donald Trump are many.

Just like Trump, Bolsonaro planted the seeds of distrust in the country’s democratic institutions – the Supreme Court included. Just like Trump, he claimed the election could be stolen and repeatedly made false claims about voting fraud during his re-election campaign. Like Trump, he didn’t concede defeat and refused to attend the inauguration of his replacement. Like Trump, he ran to Florida to nurse his bruised ego.

Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva inspects the damange at the Planalto Palace after it was stormed by supporters of his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro in Brasilia on January 8.CREDIT:AP

What is less well known, is that, like Trump, the Bolsonaro clan – three of his sons are elected MPs or senators – has had advice from and has much in common with Steve Bannon, the controversial ex-Trump White House chief strategist whose mission in life is to upend the political establishment.

As Felipe Mortara, a former veteran political journalist in Brazil, told me, Bannon and his meme-driven expressions of patriotism are extremely seductive to a large section of the population. They latch onto lies about a stolen election to justify radical responses. (Bannon himself in November posted a video saying there were no better people in the world but the Bolsonaros and claimed that all people in Brazil were fed up. “It’s going to be very interesting to see how that plays out. Use this as a warning,” he said.)

Protesters, supporters of Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro, broke through police barricades to storm the Planalto Palace in Brasilia.CREDIT:AP

The choice of Sunday for the riot, Mortara believes is also a nod to a strategy of maximum impact, he says. A day of no political competition, maximum media exposure through end-of-week popular Sunday night news programs and when most people are off work and free to travel and to foment social media.

Just like followers of Trump, supporters are clad in the country’s flag and colours, purportedly to embody the power of the people against the corrupt establishment and to speak for the oppressed. In most cases, they were radicalised via social media where posts capitalise on real discontent to create urgency, chaos and more division.

Brazilian congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, left, meets with former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon in New York in the lead up to his father's presidential election win in 2018. CREDIT:TWITTER/@BOLSONAROSP

The movement has been prominent too in France and Germany, among others.

A worrisome difference, however, are the demands by Bolsonaro supporters for military intervention – a return to the dark days of the dictatorship when hundreds of activists were disappeared, outspoken artists sought political asylum overseas and generals grew rich from corruption. They argue that in those days the country was run orderly.

Bolsonaro supporters stand on the roof of the National Congress building in Brasilia after storming it.CREDIT:AP

Nicole McLean, who heads a Brazilian politics discussion group at The University of Melbourne, said the rioting in Brazil did not come as a surprise.

“I was kind of expecting it. We know that Brazil takes their culture, society and political influence cues from the US.

“A few differences though, I have not seen Bolsonaro calling for people to act himself, and I find the focus on the STF [the Supreme Court] interesting.

“My interpretation is Bolsonaristas are acting out revenge on the STF and [Minister Alexandre] Moraes [who] was very critical of Bolsonaro.”

RELATED ARTICLE

World politics

Bolsonaro supporters storm Brazil Congress in act Lula calls ‘barbarism’

McLean, who is a doctor of social political sciences and specialist in political movements in Brazil, said the process of polarisation dates back to 2013, when members of the middle class began to engage in protests and counter-protests that culminated with the impeachment of then president Dilma Rousseff. Then, the right tried to paint itself as democratic, non-violent and non-corrupt, and the left as driven by violent radicals.

“That has completely flipped,” she says of the violence adopted by the far-right now.

“What is similar to the US, is that we have a president in Bolsonaro who was not professional in any way, and who instigated outrage against the Supreme Court and democratic institutions, which fractures the whole political structure. Having a populist leader who pushes these extreme views onto the population just feeds dissent.

“Like [what] happened in the US, people get consumed by this extremism.”

Bolsonaro supporters storm Brazil's Congress

Supporters of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro have stormed Brazilian government buildings, demanding the election result that saw him ousted be overturned.

So-called Bolsonaristas continue to call for more protests, as well as the invasion of broadcasters Globo and Bandeirantes, which they say are not reporting the events “properly”.

They want the riots to be seen as democracy at its best. History is likely to record it as a large section of the population – those on the ground and those justifying their actions – displaying it at its worst.

© Joedson Alves/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Amnesty International calls for the relevant authorities to conduct prompt, impartial and effective investigations so that the acts of this Sunday, 8 January, are appropriately investigated and sanctioned. The attacks and invasion of public buildings, destruction of documents, violations of the security and physical integrity of journalists covering the events and of security forces officers attacked by groups of civilians must be investigated. Attempts to destroy and take equipment and cameras from media professionals represent a serious violation of the right to freedom of expression and of the press.

Amnesty International will monitor the federal intervention in public security in the Federal District, decreed today by the President of the Republic, Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, in response to what happened.

It is vital that the authorities ensure the complete and immediate evacuation of the the Praça dos Três Poderes, including the National Congress, the Planalto Palace and the Federal Supreme Court. The destruction of public buildings representing institutions of the three branches of government should be investigated by the competent bodies and those responsible should be investigated, prosecuted, tried and punished, in accordance with international human rights standards.

The Brazilian state’s obligation to guarantee human rights means the authorities should be prepared to respond to political demonstrations. This requires intelligence, planning, prevention and monitoring of high-risk scenarios and groups that seek to affect the enjoyment of rights, in order to facilitate proportionate institutional reactions. International human rights standards allow the dispersion of demonstrations on specific occasions, including, for example, when they incite discrimination, hostility or violence. Today’s invasion in Brasilia does not meet international standards for a peaceful demonstration.

Today, 8 January 2023, a crowd of at least 3,900 demonstrators from civilian groups contesting the outcome of the 2022 Presidential Elections invaded the National Congress, the Planalto Palace and the headquarters of the Federal Supreme Court in Brasilia. In the early hours of Saturday, 7 January, concern was already building over the arrival in Brasilia of more than 100 buses carrying demonstrators, when the Minister of Justice and Public Security authorized the use of the National Force to carry out security at the site. The Federal District government failed to guarantee security and did not take the necessary measures to stop the violent acts and the invasion of public buildings that had already been announced by extremist groups.

Amnesty International has been observing with concern, since the first round of the presidential elections, the escalation of violence and threats to the rule of law by organized groups, in some cases armed, challenging not only the outcome of the electoral process, but also the functioning of state institutions.

It is alarming that authorities such as the Federal Police, Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Federal District and the Government of the Federal District have not been able to identify the instigators and financiers of the invasion and prevent today’s attacks from taking place.

Amnesty International demands that the Brazilian state ensure a prompt, impartial, serious and effective investigation into the circumstances that led to the invasion and attacks that took place on 8 January 2023 in Brasilia, in order to identify, prosecute, judge and hold accountable all those involved in these incidents, including the instigators, organizers and financiers, as well as the omissions of state institutions that failed to act to prevent these attacks from taking place.