In an exclusive interview, Shou Zi Chew said he’s working to persuade lawmakers that TikTok poses no threat. Things aren’t going exactly to plan.

“We have to have tough conversations on: Who is using it now? What kind of value does it bring to them? What does it mean if we just, like, rip it out of their hands?” he added. “I don’t take this conversation of ‘let’s just ban TikTok’ very lightly. … I don’t think it’s a trivial question. I don’t think it should be something that’s decided, you know, in 280 characters.”

The married father of two, a Harvard Business School graduate based in his native Singapore, spent Tuesday in the halls of Congress trying to convince lawmakers that the company is not run — as some argue — by Chinese government lackeys, propagandists or spies.

It’s unclear whether the strategy will pay off. After he met with Sen. Michael F. Bennet, the Colorado Democrat’s staff caught TikTok officials by surprise by announcing that, while the senator appreciated Chew’s time, he remained unconvinced, arguing that TikTok was “an unacceptable risk to U.S. national security” and threatened a “poisonous influence” on American teens.

TikTok said it respectfully disagrees with Bennet’s characterization of its company and will continue to work on educating members of Congress and building trust.

TikTok is not without friends in the United States. Chew arrived in Washington this week after attending the Super Bowl, where an official with TikTok parent ByteDance said he was a guest of NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell. The league is a major promotional partner of the app, where videos of big plays are viral and heavily promoted, including by the NFL’s 10 million-follower official account.

Chew even broadcast the halftime show in a TikTok video: “Amazing @rihanna !,” he said.

An NFL spokesman didn’t dispute Chew’s attendance but said he was not in the commissioner’s suite. Still, that’s better than the welcome he’s getting in Washington. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), who met with Chew this week, told The Post he did so “as a courtesy” but that his belief that TikTok represented a unique threat to American interests was completely unchanged.

And what was once a Republican-led crusade against TikTok has attracted some Democratic endorsement. Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), whose daughter works for Facebook, said Sunday that a TikTok ban “should be looked at.”

“I don’t think there’s anything they can say,” said Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii). “It’s all about what they do, and what they do is pretty alarming.”

TikTok’s executives had for years hoped the company’s backroom negotiations with national security officials — and its viral-dance-filled self-promotion as the “last sunny corner of the internet” — would neutralize suspicions in Washington over the app’s China-based ownership.

But with criticism heating up, Chew has launched a room-to-room offensive on Capitol Hill, meeting with federal and state lawmakers, journalists and think tanks in an effort to persuade critics that concerns about data privacy and censorship can be resolved without the nuclear option of a nationwide ban.

Asked if they’d gained any allies in Washington, TikTok officials this week suggested Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who’d recently offered some mild support of the company’s “working with U.S. intelligence” on “proper precautions.” Booker’s representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

“We understand we start from a place of trust deficit,” Chew said, “and that trust is not won by one move, one silver bullet, one meeting.”

Chew said he is hopeful that members of Congress will come around to see TikTok as many of its users do, a place for creativity and free expression, and acknowledge that some of their anxieties about online data or teenage use relate to bigger issues that should be resolved by industry-wide policy instead of a single-app ban.

But he said he has also had to navigate discussions with people who have never used TikTok but still argue in tweets and TV interviews that the app is an insidious threat — and that the company’s arguments are compromised, foolish or naive.

Many of the suspicions he’s tried to address, he said, have been “misinformed” or based on “misrepresentations.” TikTok officials have also been frustrated by what they feel is unfair influence from TikTok’s top competitor, the Facebook and Instagram parent company Meta, which has funded a secret media and lobbying campaign to portray the app as a foreign-owned threat to American youth.

“We should be competing on product and user experience,” Chew said. “That’s the right way to compete.”

TikTok is a private company with major Western investors, nearly a dozen international offices and thousands of American employees. But its parent company, ByteDance, was created by Chinese founders and operates a central office in Beijing — a fact that U.S. lawmakers have argued could leave them vulnerable to China’s authoritarian style of online surveillance and media control.

The U.S. government has shared no evidence that the Chinese Communist Party has mined TikTok’s data for information on American users or warped its recommendation algorithm to score political points. But both concerns have become prominent themes of criticism in the United States, leading to regular attacks on the app in Washington and more than two dozen state-device bans.

TikTok officials have started preparing Chew for his first major congressional appearance next month before the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and most expect he will be grilled relentlessly. His deputy, Chief Operating Officer Vanessa Pappas, sat for a fiery hearing in September during which Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) labeled TikTok a “walking security nightmare.”

TikTok says it has spent $1.5 billion — and expects to spend another $700 million a year — standing up a corporate restructuring plan, known as Project Texas, that would subject the company to a level of U.S. government influence and oversight unmatched by any of its American rivals

TikTok’s U.S. operations would be sequestered in a subsidiary, known as TikTok U.S. Data Security, whose leaders would be vetted by the U.S. government and whose U.S. user data would be closely monitored and firewalled.

Some measures have already been launched, including the opening last month of a code-review center in Columbia, Md., where officials from the Texas-based tech giant Oracle can inspect TikTok’s algorithm and source code for possible flaws. TikTok officials have argued to lawmakers that this style of intense government monitoring and compliance is more commonly seen with military or defense contractors, not social media apps.

But the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, the cross-government panel known as CFIUS that has led negotiations between TikTok and the U.S. for three years, has yet to approve the restructuring package or publicly state any outstanding concerns.

Chew said TikTok gave CFIUS a full blueprint of the proposal in August and that the company is “still waiting for feedback.” A CFIUS official did not respond to a request for comment.

Some in Washington point to risks such as a Chinese law that allows the government to compel tech companies to hand over user data to assist with “national intelligence” work.

Chew said that the Chinese government has never asked for U.S. user data and that, “even if they did, we believe we don’t have to give it to them because U.S. user data is subject to U.S. law.”

But critics such as Klon Kitchen, a senior fellow at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, argue that TikTok’s promise is a meaningless “smokescreen,” and that only a complete divestiture from Chinese ownership can address the concerns.

“They don’t have to be malevolent actors, they simply have to be compliant,” Kitchen said. “And for Chinese companies, either you’re compliant or you’re out of business.”

TikTok’s owner, ByteDance, also undermined its argument in December when it announced it had fired four employees for trying to use TikTok data — including IP addresses, which can provide rough estimates of locations — to hunt down journalists’ sources.

Chew called the instance “very disturbing” and blamed it on a “completely misguided” group of employees acting without corporate approval. He noted that the leader of the group was an American and said the company had started restructuring its internal-audit team to prevent it from happening again.

“We didn’t want to hide this or sweep it under the rug,” he said. “Bad actors and instances like this really sort of erode all the work that we have done.”

Chew, a former Facebook intern and ByteDance finance chief who became TikTok’s CEO in 2021, said he is in charge of all of TikTok’s strategic decisions. But ByteDance has played an active role in TikTok’s shift to defend itself more aggressively in Washington, Chew said, and he could not provide a specific instance on which he had pushed back against a decree from ByteDance’s leadership.

Chew said he routinely updates ByteDance chief and co-founder Liang Rubo on “certain topics that I think he may have an interesting point of view, just to make sure the perspective is complete.”

Chew’s meetings come at a tense moment for U.S.-China relations as lawmakers discuss how to respond to a Chinese spy balloon, whose presence some critics used to highlight TikTok’s potential for spying or propaganda — even though the app shared hours of colorfully subversive videos related to the episode, many from an unfiltered American point of view.

“We cannot be removed from the larger discussion. But that’s not really our business. … It’s a distraction,” Chew said. “We are not the first nor the last company to be associated with all sorts of unfair analogies.”

Though an executive on par with Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk, Chew remains almost entirely unknown, both on Capitol Hill and in the general public. His TikTok account (“shou.time”) has 17,000 followers and features mostly touristy style videos of attending the Met Gala, posing for photos with celebrities such as Bill Murray, and visiting TikTok’s offices in Los Angeles and New York. (In a video styled after TikTok’s “teenage dirtbag” viral challenge, Shou, 40, showed photos of himself as a young man growing up in Singapore.)

His public persona could change after next month’s hearing — including, possibly, to cement him as the face of a company some in Congress argue could warp the brains of American youth. But he said he is hopeful that lawmakers will one day see his side.

“I am a very big believer that, ultimately, facts win,” he said. “Ultimately, people are rational. Yes, it will feel uncomfortable at times. But I think we are trending in the right direction by bringing more facts to the table.”

Cristiano Lima contributed to this report.

By Drew HarwellDrew Harwell is a reporter for The Washington Post covering artificial intelligence and the algorithms changing our lives. He was a member of an international reporting team that won a George Polk Award in 2021.

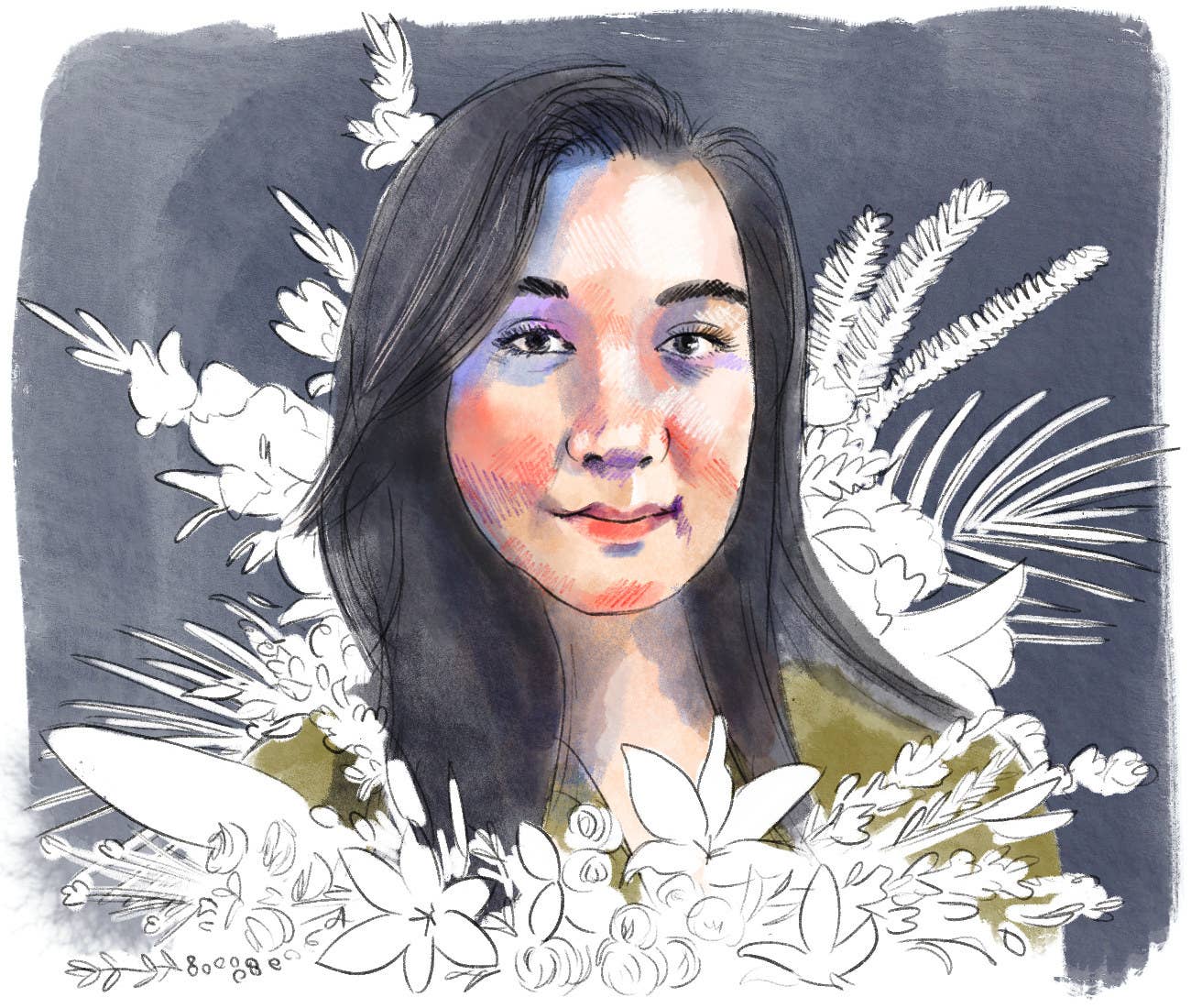

Brianna Ghey is shown in this undated photo released by the Cheshire Police

Brianna Ghey is shown in this undated photo released by the Cheshire Police