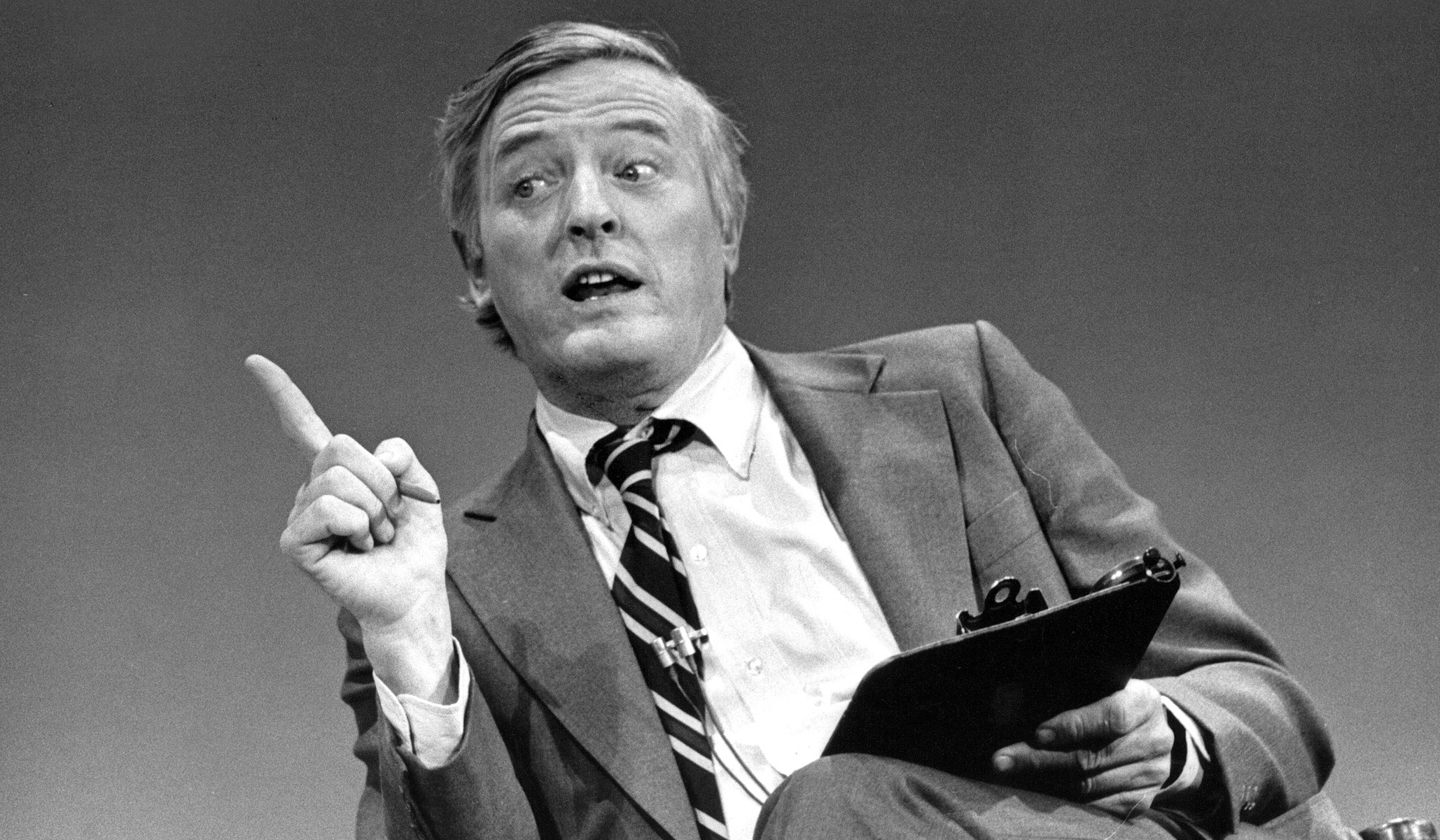

National Review founder William F. Buckley Jr.(National Review)

By ALVIN S. FELZENBERG

April 23, 2023

His full-scale attack on the John Birch Society was a turning point. He emerged from the controversy in the role of ‘tablet keeper’ of the conservative movement.

‘Of all the crusades William F. Buckley took on in his half century on the national political stage,” I wrote in 2017, “none did more to cement his reputation as a gatekeeper of the conservative movement — or consumed more of his time — than that which he launched against the John Birch Society.”

But was his heart really in it? Matthew Dallek in his Politico discussion of William F. Buckley Jr. and the John Birch Society offers a resounding “no.” He debunks what he calls “a popular idea that Buckley cordoned off the Birchers and expelled them” from the conservative movement. He goes as far as to declare the action so many of Buckley’s admirers across the political spectrum consider his “finest hour” a “myth.” Dallek concedes that Buckley moved against JBS founder Robert Welch but states that he did not truly attack the organization Welch founded. Not so.

In the early 1960s, Buckley condemned Welch in the strongest possible terms. He feared that the liberal establishment and the Rockefeller wing of the GOP would use Welch’s comments (especially his characterization of Eisenhower as a “dedicated, conscious agent” of an international communist conspiracy) to cast all conservatives as “extremists,” and, therefore, unfit for public office or to influence public opinion.

Early in that decade, few, whether on the left or on the right, regarded William F. Buckley Jr. as the recognized leader of the conservative movement. Barry Goldwater was. And, as Dallek points out, Goldwater was in no mood to take on Welch’s organization, whose members Goldwater considered “nice people” (an assessment he voiced at a meeting with Buckley plotting how to disentangle conservatism from Bircherism). National Review followed Goldwater’s lead and limited its criticism of the JBS to Welch. That was then.

More on

By ALVIN S. FELZENBERG

April 23, 2023

His full-scale attack on the John Birch Society was a turning point. He emerged from the controversy in the role of ‘tablet keeper’ of the conservative movement.

‘Of all the crusades William F. Buckley took on in his half century on the national political stage,” I wrote in 2017, “none did more to cement his reputation as a gatekeeper of the conservative movement — or consumed more of his time — than that which he launched against the John Birch Society.”

But was his heart really in it? Matthew Dallek in his Politico discussion of William F. Buckley Jr. and the John Birch Society offers a resounding “no.” He debunks what he calls “a popular idea that Buckley cordoned off the Birchers and expelled them” from the conservative movement. He goes as far as to declare the action so many of Buckley’s admirers across the political spectrum consider his “finest hour” a “myth.” Dallek concedes that Buckley moved against JBS founder Robert Welch but states that he did not truly attack the organization Welch founded. Not so.

In the early 1960s, Buckley condemned Welch in the strongest possible terms. He feared that the liberal establishment and the Rockefeller wing of the GOP would use Welch’s comments (especially his characterization of Eisenhower as a “dedicated, conscious agent” of an international communist conspiracy) to cast all conservatives as “extremists,” and, therefore, unfit for public office or to influence public opinion.

Early in that decade, few, whether on the left or on the right, regarded William F. Buckley Jr. as the recognized leader of the conservative movement. Barry Goldwater was. And, as Dallek points out, Goldwater was in no mood to take on Welch’s organization, whose members Goldwater considered “nice people” (an assessment he voiced at a meeting with Buckley plotting how to disentangle conservatism from Bircherism). National Review followed Goldwater’s lead and limited its criticism of the JBS to Welch. That was then.

More on

CONSERVATISM

William F. Buckley Sr.: Father of a Revolution

The Inside Story of William F. Buckley Jr.’s Crusade against the John Birch Society

Goldwater’s national influence within the conservative movement began to decline after his landslide defeat to LBJ in the 1964 presidential election. In 1965, Buckley, as a candidate for mayor of New York City running against a liberal Republican and a liberal Democrat, wasted no time ferreting the John Birch Society out of the movement he helped found. That is what Dallek misses.

In August 1965, Buckley published three columns — both nationally and in National Review — taking the JBS to task. In a special issue of the magazine, he ran supportive commentary by Goldwater, Senator John Tower, and retired admiral William Radford. In the first essay, Buckley referenced ten JBS positions, all culled from a single issue of its magazine, American Opinion. Each statement took as its premise that large segments of the United States government were under communist control. Buckley inquired how the society’s membership could tolerate “such paranoid and unpatriotic drivel.” Elsewhere, he urged Birchers who disagreed with these positions to leave the society and beseeched readers of his own magazine to disassociate themselves politically from those who adhered to such positions.

In his attempt to draw parallels between Buckley’s actions then and Republicans of today seeking to draw distinctions between Trump and Trumpism, Dallek downplays the hailstorm Buckley brought down on himself and his magazine. Dallek refers to this as an “underappreciated price”: He “lost some subscribers; he endured barbs from allies as a result of his editorials, which had put him in the crosshairs of many leaders of the far right.” This is an understatement, to say the least. The cost was serious. So much so that, alarmed at the hemorrhaging of fleeing subscribers and donors NR was experiencing after Buckley’s scorching criticisms of the JBS, conservative columnist James Kilpatrick turned his column into a beg-a-thon to keep National Review afloat.

Undeterred, Buckley, in a photograph published by Life Magazine, delighted in holding up a one-word letter he received from an enraged Bircher. (Across the page was scribbled in Magic Marker the word “Judas.” Others proclaimed him a “traitor.”) With the Birchers attacking him so vigorously, Buckley’s liberal opponents gained little traction when they tried to portray Buckley as an “extremist.” Ditto today, as Dallek tries to fault Buckley for failing to stop the sort of radicalism, such as the January 6 Capitol riot, that his successors at NR condemned. Indeed, Buckley’s full-scale attack on the John Birch Society was a turning point for him and for the conservative movement. Buckley emerged from the controversy having assured his place as “tablet keeper” of the conservative movement, a role to which he had long aspired. It does his labors a disservice to belittle them as mere “fence-walking.”

NEXT ARTICLETrump on Late-Term Abortion: Promises Made, Promises Broken?

ALVIN S. FELZENBERG is the author of A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. and The Leaders We Deserved: Rethinking the Presidential Rating Game.

ALVIN S. FELZENBERG is the author of A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. and The Leaders We Deserved: Rethinking the Presidential Rating Game.

William F. Buckley Sr.: Father of a Revolution

The Inside Story of William F. Buckley Jr.’s Crusade against the John Birch Society

Goldwater’s national influence within the conservative movement began to decline after his landslide defeat to LBJ in the 1964 presidential election. In 1965, Buckley, as a candidate for mayor of New York City running against a liberal Republican and a liberal Democrat, wasted no time ferreting the John Birch Society out of the movement he helped found. That is what Dallek misses.

In August 1965, Buckley published three columns — both nationally and in National Review — taking the JBS to task. In a special issue of the magazine, he ran supportive commentary by Goldwater, Senator John Tower, and retired admiral William Radford. In the first essay, Buckley referenced ten JBS positions, all culled from a single issue of its magazine, American Opinion. Each statement took as its premise that large segments of the United States government were under communist control. Buckley inquired how the society’s membership could tolerate “such paranoid and unpatriotic drivel.” Elsewhere, he urged Birchers who disagreed with these positions to leave the society and beseeched readers of his own magazine to disassociate themselves politically from those who adhered to such positions.

In his attempt to draw parallels between Buckley’s actions then and Republicans of today seeking to draw distinctions between Trump and Trumpism, Dallek downplays the hailstorm Buckley brought down on himself and his magazine. Dallek refers to this as an “underappreciated price”: He “lost some subscribers; he endured barbs from allies as a result of his editorials, which had put him in the crosshairs of many leaders of the far right.” This is an understatement, to say the least. The cost was serious. So much so that, alarmed at the hemorrhaging of fleeing subscribers and donors NR was experiencing after Buckley’s scorching criticisms of the JBS, conservative columnist James Kilpatrick turned his column into a beg-a-thon to keep National Review afloat.

Undeterred, Buckley, in a photograph published by Life Magazine, delighted in holding up a one-word letter he received from an enraged Bircher. (Across the page was scribbled in Magic Marker the word “Judas.” Others proclaimed him a “traitor.”) With the Birchers attacking him so vigorously, Buckley’s liberal opponents gained little traction when they tried to portray Buckley as an “extremist.” Ditto today, as Dallek tries to fault Buckley for failing to stop the sort of radicalism, such as the January 6 Capitol riot, that his successors at NR condemned. Indeed, Buckley’s full-scale attack on the John Birch Society was a turning point for him and for the conservative movement. Buckley emerged from the controversy having assured his place as “tablet keeper” of the conservative movement, a role to which he had long aspired. It does his labors a disservice to belittle them as mere “fence-walking.”

NEXT ARTICLETrump on Late-Term Abortion: Promises Made, Promises Broken?

ALVIN S. FELZENBERG is the author of A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. and The Leaders We Deserved: Rethinking the Presidential Rating Game.

ALVIN S. FELZENBERG is the author of A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. and The Leaders We Deserved: Rethinking the Presidential Rating Game.