Researchers show endangered parrot species is thriving in urban areas

A Texas A&M-led research team has discovered that a population of endangered red-crowned parrots is thriving in urban areas of South Texas. The parrots are a unique case, considering that many animal species are affected negatively by the expansion of human urban areas, which can lead to deforestation and pollution of natural habitats.

These mostly green parrots, which have a cluster of bright red feathers on their heads, are also an unusual example of a species that has adapted well in the face of poaching and the pet trade moving them from their native areas.

The team—led by Dr. Donald J. Brightsmith and graduate student Simon Kiacz, from the School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences' (VMBS) Department of Veterinary Pathobiology—recently published its findings in the scientific journal Diversity.

The team's documentation of the red-crowned parrot's habitat ranges and urban dependency will enable the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department and other conservationists to better protect these endangered birds.

Meet the red-crowned parrot

Red-crowned parrots were originally native to a small region of Northeastern Mexico, where they are considered endangered because of habitat loss and poaching tied to the illegal animal trade. For parrots, this process often involves poachers stealing eggs or young chicks out of nests and selling them, sometimes for hundreds of dollars each.

"Parrots are popular pets in places like South Texas and Latin America," Kiacz said. "Unfortunately, most people, even law enforcement officers, don't realize that these parrots are protected."

In fact, the animal trade is one reason that the red-crowned parrots can now be found in Texas.

"Some of them certainly flew across the border, but many were brought over during the 1980s when it was still legal to buy and sell them," Brightsmith said.

Over time, Texas has welcomed the red-crowned parrot, even giving it native species status.

"Without native species status, it would be much more difficult to provide protection for the species," Brightsmith said.

One benefit of being a native species is that Texas Parks & Wildlife took interest in research seeking to better understand whether the parrots are doing well in South Texas. That interest is what paved the way for Brightsmith and Kiacz's project.

"During data collection, I was looking for population information, trend information, the threats to the populations here in Texas, and habitat usage," Kiacz said. "We wanted to understand how these birds are doing and what we might be able to do to help them."

By counting birds and mapping their habitat ranges, the researchers eventually discovered that the red-crowned parrots appear to be doing very well in South Texas. They're especially prevalent in areas in the Rio Grande Valley, including towns like Brownsville, which even made the red-crowned parrot its official mascot.

"There are four main roosts in South Texas," Kiacz said. "Brownsville, Harlingen, Weslaco and McAllen all have a group of parrots living in those communities. We used trackers, mapping software and local knowledge to see where these birds were roosting, and then we just had to count them." He said the South Texas population is around 900 birds.

"We can get a really good idea of the population's breeding activity this way," he explained. "If there is a decrease in the number of birds at the roost in the breeding season, that's a good thing, because the females are probably nesting somewhere else with their offspring. Then in the fall, we'll see all the juveniles join the adults at the roost."

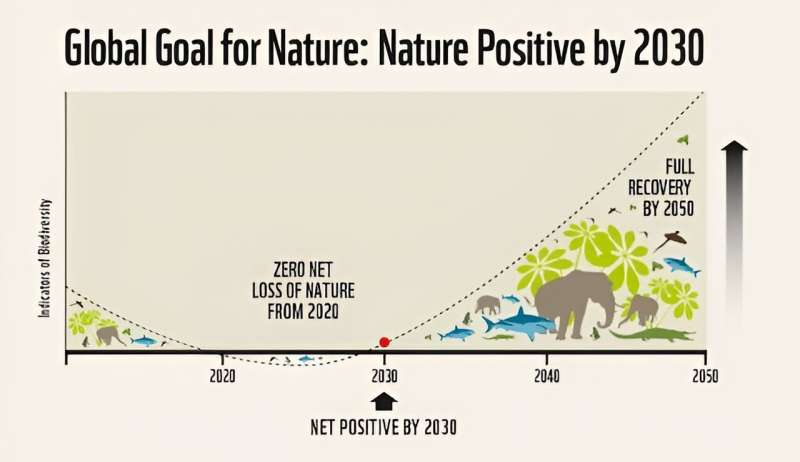

The species' success is unusual given that endangered species of plants and animals are rarely found thriving in urban environments. Most of the time, species that have adapted to urban environments—called "synanthropes"—are considered neutral, or even invasive.

Instead, it seems that red-crowned parrots are able to get along quite well with people.

"Humans have basically created the perfect environment for these parrots," Kiacz said. "They want what we want—ornamental plants with fruit and seeds that are well-watered and look attractive all year-round."

Even our habit of planting palm trees where they don't tend to survive is a boon for these birds.

"All of the palm trees that we plant in South Texas are non-native," Kiacz explained. "They eventually die, and then woodpeckers come and make holes that are perfect nesting cavities for these parrots. But they're also happy to use holes in the sides of buildings."

Since the parrots love to eat non-native species of plants, they haven't caused much competition with other local species over food sources. Currently, the only downside to the presence of these parrots is the noise.

"You'll often see these birds roosting together," Brightsmith said. "They sleep in groups of a hundred or more, and they may end up choosing someone's front yard, even right over the mailbox. Then, when it gets light outside, they'll start making noise and flying around. Some people find that to be a nuisance."

Life finds a way

If there's one thing to learn from the new research on red-crowned parrots, it's that life finds a way. As urbanization continues to spread around the globe, it's likely that more and more species will move into urban spaces, perhaps with unexpected results.

And while it isn't necessarily a good thing that these species are being forced to change their survival tactics, there may be similar unique opportunities for research in the future.

Currently, Brightsmith and Kiacz are working on new projects that will study the relationships between red-crowned parrots and sister species, like the lilac-crowned parrot, including natural hybridization that may be entangling the two species from a conservation standpoint.

For now, the pair of researchers hope that their work will raise awareness about red-crowned parrots and lead to improved conservation efforts.

"What we actually need is for people to understand how these birds live in urban environments," Kiacz said. "Instead of trying to fund large nature preserves, which you might need to do for other species, the best help we can give these parrots is to teach people how to live with parrots as neighbors.

"For example, maybe you have a dead tree in your yard that doesn't look very pretty, but it's not a danger to you or your home," he explained. "Consider keeping it so these parrots can nest there."

More information: Simon Kiacz et al, Presence of Endangered Red-Crowned Parrots (Amazona viridigenalis) Depends on Urban Landscapes, Diversity (2023). DOI: 10.3390/d15070878

Provided by Texas A&M University Canberra's superb parrots caught up in housing crisis