Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, French pioneer of ‘microhistory’ whose study of Montaillou was a bestseller – obituary

Thu, 23 November 2023

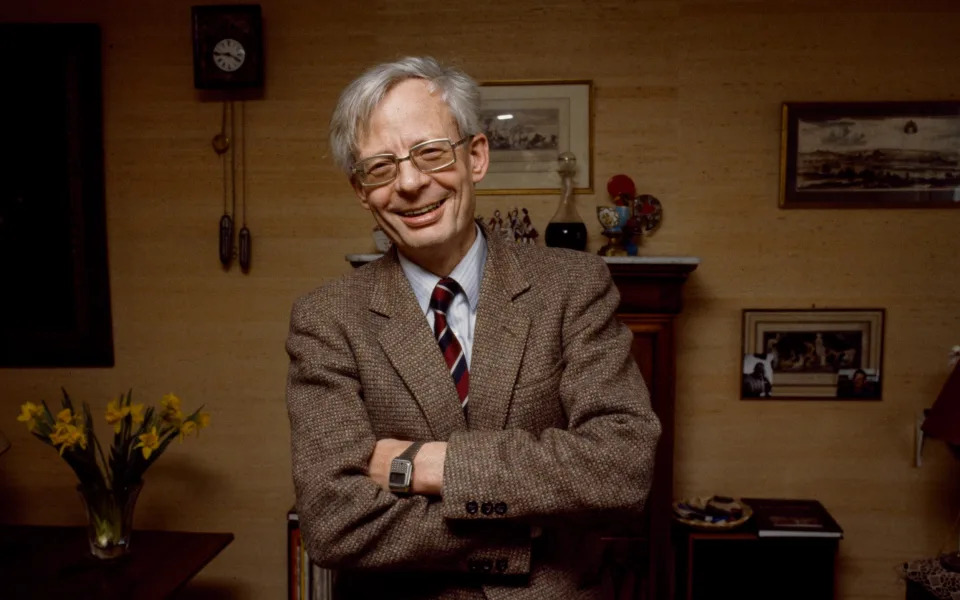

Ladurie: a ‘truffle hunter’ who broke conventions of historical research

Professor Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, who has died aged 94, was director of the French Bibliothèque nationale, Professor at the Collège de France and a leading exponent of the “annales” school of history; he was best-known for Montaillou (1975), a reconstruction of 15th-century peasant life in a Pyrenean village that became an international bestseller.

Ladurie once divided historians into two groups – “truffle hunters” and “parachutists”. Truffle hunters are miniaturists, lovingly recounting histories of minor and exotic events, case studies of the strange, novel and unexpected that, despite their uniqueness, cast light on their times.

Parachutists take a panoramic view, highlighting the grand sweep and emphasising big trends rather than particulars. Since he was a gourmet with a French appreciation of haute cuisine, there was little doubt as to which school of history Ladurie belonged.

Montaillou is a hamlet high up on the French slopes of the Pyrenees which, in the early 14th century, had about 400 inhabitants. Many of them were Cathars – devotees of a heresy which taught that the world had been created by the Devil as his battleground with God.

In the previous century a succession of crusades had been proclaimed against its adherents and the heresy had all but disappeared. But in the early 14th century, a Bishop of Pamiers called Jacques Fournier (later Pope Benedict XII) decided to have another go at eliminating Catharism, which had experienced a sudden revival in his diocese in the area around Montaillou.

The bishop set up his own personal inquisition which sat for eight years. The whole population of Montaillou was clapped into jail and interrogated one by one. Subsequently, he had his inquisitorial register, containing their depositions and confessions, transcribed into folio volumes which he kept with him when he became Pope and which remain in the Vatican library.

Jacques Fournier’s register had been known to scholars for many years, but to the prevailing “parachutist” school it seemed to be of no more than antiquarian interest. Ladurie saw its scholarly value in illuminating a little known period of history, and its popular potential in satisfying public curiosity about the lives of ordinary people in the distant past.

Montaillou: history from below

Fournier’s register offered vivid insights into almost every aspect of village life in the late middle ages – not just the religious beliefs of the villagers but their social relations, their work, their food, their superstitions, their recreations and their often scandalous sex lives.

“The study of Montaillou,” Ladurie wrote, “shows us on a minute scale what took place in the structure of society as a whole. Montaillou is only a drop in the ocean. Thanks to the microscope provided by the Fournier Register, we can see the protozoa swimming about in it.”

The arch-villain of Montaillou, the colourful and roguish Pierre Clergue, priest of the village, helped himself to a large number of the local women, not excluding his own sisters and sisters-in-law, on occasion even in church. When he encountered resistance, he sometimes found it useful to mention the Inquisition.

Ladurie’s Montaillou became a celebrated publishing success, was translated into many languages and sold hundreds of thousands of copies in France and abroad. It established a vogue for “microhistory” in universities around the world. Eamon Duffy’s Voices of Morebath (2001) is a more recent example of the genre.

Emmanuel Bernard Le Roy Ladurie was born at Moutiers-en-Cinglais in the Calvados region of Normandy on July 19 1929. Educated by an order of friars whom he sometimes referred to as the Ignorant Brothers, he sat a baccalaureat from which History had been suppressed by the Vichy authorities.

His family was divided by the Second World War. His father, Jacques, served as a minister of agriculture in the Vichy regime and remained loyal to Pétain. Other members of his family worked for the Resistance.

The aftermath of war brought on an intense personal crisis in which Ladurie felt compelled, while studying History at the Sorbonne, to question the values of his family, his religion and his country. He joined the Communist Party, becoming a firm adherent of Marx and Durkheim.

Events such as the death of Stalin and Khrushchev’s “secret speech” of 1956 helped precipitate his detachment from the party, but it was also a growing commitment to historical professionalism that estranged him and gave him a new basis for understanding the world. He wrote of his shock when he realised that a disgraced French Communist leader had been airbrushed from a historical photograph in a party publication.

After graduating from the Sorbonne, Ladurie worked as a teacher at the Lycée de Montpellier for two years before becoming a resident assistant at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and then at the Faculté des Lettres de Montpellier. In 1963 he became a lecturer and director of studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, then lecturer at the Faculté des Lettres de Paris.

In 1970 he was appointed professor at the Sorbonne. He served as Administrateur Général of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (1987-94) and was appointed Professor of History of Modern Civilisation at the Collège de France in 1979.

If Ladurie moved away from communism, he retained a zeal for “quantitative” history and “history from below”, in which the lives of ordinary people have as much value as those of kings and statesmen. His first major study, The Peasants of Languedoc, was hailed as a pioneering work of “total history” when it was published in France in 1966.

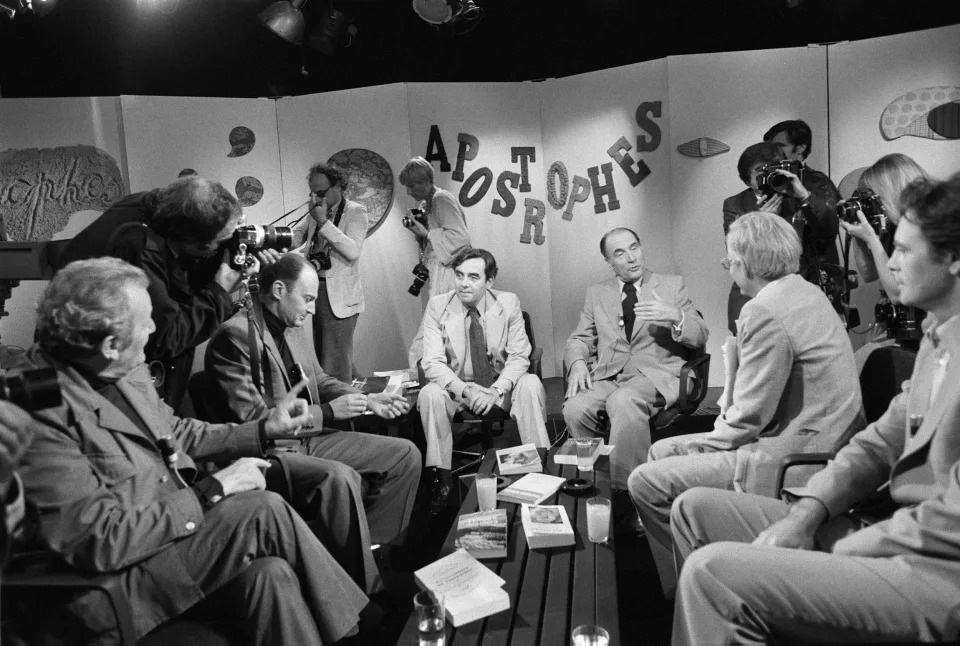

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, second from right, being addressed by Francois Mitterrand in the television programme Apostrophes with other guests, Paris, 1978 - Alain MINGAM/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

It combined elements of human geography, historical demography, economic history and folk culture in an account of the problems of a traditional peasant society in which the rise in population was not matched by increases in wealth and food production.

Ladurie retained a rebel’s delight in breaking the conventions of historical research. On one occasion he bombarded 16th-century coins with neutrons to test whether they originated from the silver mines of Potosi. In 1973 he wrote a History of Climate since 1000, using the science of dendrology to assess periods of warmer and cooler weather.

In later life he became a fervent advocate of European federalism. At a low point in Anglo-European relations in 1994, he suggested that reconciliation could be achieved if the British only admitted the “prodigious advantage” their language gave them in the fields of culture, trade and science, and compensated for this boon by “agreements on the price of artichokes and lobster”.

He traced Britain’s hostility to the idea of a federal Europe to the “papist” origins of the movement in the 1950s. He described Robert Schuman, the French foreign minister who, together with Jean Monnet, is considered the architect of the European integration project, as “almost a saint for the Catholic Church because he died a virgin”.

Ladurie’s numerous other works include Le Territoire de l’historien (two volumes, 1973 and 1978), Carnival in Romans (1980), an account of uprising and subsequent slaughter of commoners during the Mardi Gras of 1580 and The Beggar and the Professor (1997), a rags-to-riches non-fiction tale set during the religious ferment of the 16th century. His last book, Brève histoire de l’Ancien Régime, was published in 2017.

Ladurie was a Grand Officer of the Légion d’honneur, and a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

He married, in 1956, Madeleine Pupponi; they had a son and a daughter.

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, born July 19 1929, died November 22 2023

Pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu

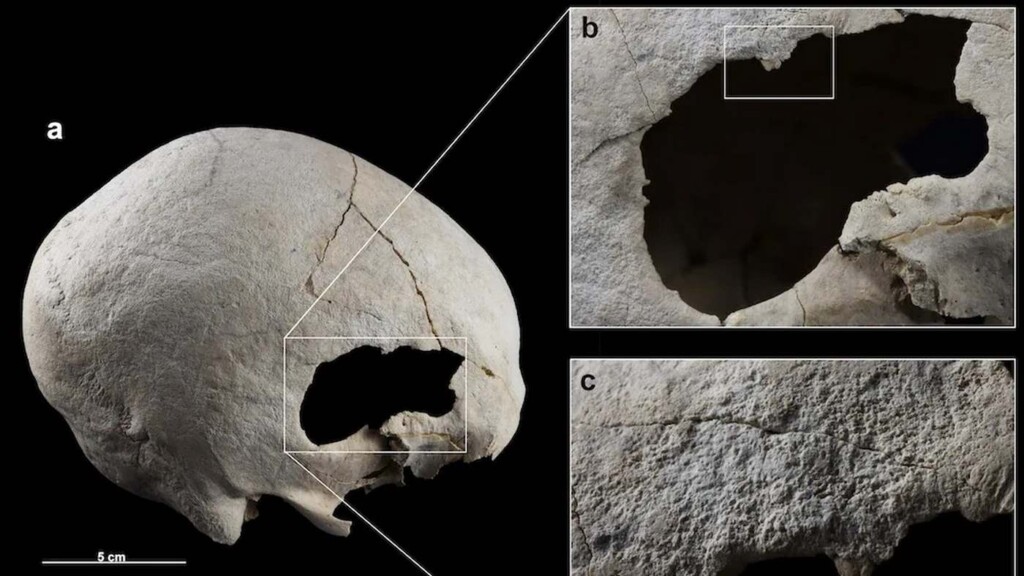

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)