Alzheimer's Was 'Exceptionally' Rare in Ancient Greeks And Romans, Study Suggests

Older people in ancient Greece and Rome may not have experienced severe memory problems like many who are aging today.

Researchers in California have combed through a slew of classical texts on human health written between the 8th century BCE and 3rd century CE, and found surprisingly few references to cognitive impairment in older folk.

According to Caleb Finch, who studies the mechanisms of aging at the University of Southern California, and historian Stanley Burstein from California State University, severe memory loss may have been an extremely rare outcome of growing old more than 2,000 years ago.

And that's not because ancient Romans and Greeks weren't living to a ripe old age.

While average life expectancy before the common era was roughly half of what it is today, the age of 35 was hardly considered 'old' for the time. The median age of death in ancient Greece was, by some estimates, closer to 70 years, which means that half of society was living even longer than that. Hippocrates himself, the famous Greek physician and so-called father of medicine, is thought to have died in his 80s or 90s.

Age is currently known as the single greatest risk factor for dementia, with roughly a third of all people over 85 suffering from the condition today. Diagnoses over the age of 65 have been doubling every five years.

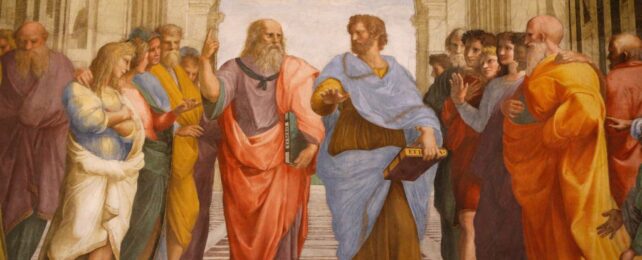

Memory loss is a highly common feature of aging in the modern world, but it wasn't always so. In the ancient past, Finch and Burstein found not one mention of memory loss in medical writings from Hippocrates, his later followers, or even Aristotle.

In Greek texts from the 4th and 3rd century BCE, old age was associated with many symptoms of physical decline, including deafness, dizziness, insomnia, blindness, and digestive disorders. But based on the available literature – which is, admittedly, limited – severe memory issues didn't seem to be a notable problem.

"We did not find any equivalent to modern case reports of [Alzheimer's disease and related dementias]," write Finch and Burstein.

"None of these ancient accounts of cognitive loss can be considered clinical-grade data in the modern sense."

The findings of the historical review suggest that today's epidemic of dementia, experienced by numerous nations around the world, could very well be a product of modern life. Indeed, recent studies have tied dementia and its most common subtype, Alzheimer's disease, to cardiovascular issues, air pollution, diet, and disadvantaged neighborhoods in urban environments, all of which are common afflictions of modernity.

In ancient times, however, Finch and Burstein found evidence that while "mental decline was recognized", it was "considered exceptional."

In the time of Aristotle and Hippocrates, they say, only a few texts mention symptoms that could indicate early- or mid-stage Alzheimer's disease, with no mention of major losses in memory, speech, or reasoning.

Even the Roman statesman, Cicero, provided no mention of memory loss in his texts on the 'four evils' of old age, which suggests it was still an unusual symptom of age as late as the mid-1st century BCE.

Not until Finch and Burstein reached historical texts from the 1st century CE did the duo find any mention of severe, age-related memory loss. The first advanced case was written down by Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 CE, and describes a famous senator and orator in Rome who forgot his own name with age.

In the 2nd century the personal physician to the Roman emperor, a Greek physician named Galen, wrote about survivors of two plagues who apparently could not recognize themselves or their friends.

By that time, air pollution was prevalent in Imperial Rome and lead exposure from cooking vessels and the civilization's plumbing system was rampant.

Such factors could have put the populace at greater risk of Alzheimer's disease, triggering unusual symptoms of old age that were rarely seen in times gone by, suggest Finch and Burstein.

Without more data, it's impossible to say why severe symptoms of dementia feature more often in records of Imperial Roman than those in ancient Greece.

The fact that there are societies of people living today that have rates of dementia less than a percent supports the theory that environmental factors could impact cognitive decline more so than aging.

The modern Tsimané and the Moseten people of the Bolivian Amazon have an 80 percent lower incidence of dementia than the US or Europe. Their brains don't seem to age like those elsewhere in the world, and their way of life is not founded on industrialization or urbanization, but is based on traditional methods of farming and foraging.

Finch and Burstein are now calling for a "broader inquiry" into the history of dementia in ancient and pre-modern times to figure out when and why severe memory losses first began to show up in older folk.

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.