Imperialist sanctions, crony capitalism and Venezuela’s Long Depression: An interview with Malfred Gerig

Malfred Gerig is a sociologist from the Universidad Central de Venezuela (Central University of Venezuela) who directs the Political Economy of Venezuela research program at the Caracas-based Centro de Estudios para la Democracia Socialista (Centre of Studies for Socialist Democracy). He is the author of La Larga Depresión venezolana: Economía política del auge y caída del siglo petrolero (Venezuela’s Long Depression: Political economy of the rise and fall of the oil century) In this extensive interview with Federico Fuentes for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, Gerig situates the impact of United States’ sanctions on Venezuela and the rise of Venezuela’s crony capitalism within the context of the nation’s “Long Depression”.

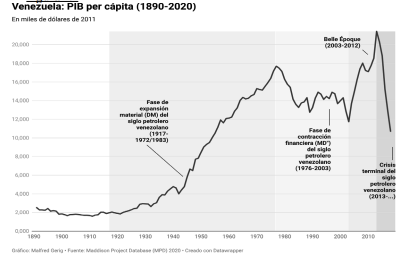

Some blame sanctions for the economic crisis in Venezuela. Others point to economic mismanagement by the government of President Nicolás Maduro. But you pinpoint 2013 as the start of what you term a “Long Depression”, which precedes the sanctions and any shift in government policies. Why?

The first thing to understand about Venezuela’s economy is that this crisis is the result of how capital accumulation occurs in Venezuela, along with the way it was inserted into the world capitalist economy during Venezuela’s “ oil century” and [what Italian economist Giovanni Arrighi terms] the US’ systemic cycle of accumulation.

Venezuela was inserted into the world economy as an oil supplier. As a result, it became a rentier country, because its state claims sovereignty over this natural resource and collects an international rent or payment for use of its property. This generates a pattern of national capital accumulation known as rentier capitalism, which is a sui generis national capitalist economy as its metabolisation of capital is dependent on the surplus that the state captures from the world capitalist economy.

I have divided this period of [Venezuela’s oil century] into two main stages. The first was the boom stage, which ran from the start of this insertion in 1914-17 until the 1970s. For most of this period, Venezuela was the world’s leading oil exporter. Its economy expanded at an accelerated rate, taking it from the most backward economy in South America to first in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita.

But the 1970s marked the start of a crisis period that emerged out of abundance. The crises of rentier capitalism perfectly fit within French physician and economist Clément Juglar maxim: “The only cause of depression is prosperity.” This prosperity came as a result of the 1973 oil crisis and concurrent rise in oil prices, along with the first Carlos Andrés Pérez government’s oil nationalisation and “Big Push” project for rapid industrialisation.

After a crisis at the end of the 1970s, the 1980s began with another crisis. This one has a specific date — February 18, 1983, known as “Black Friday” — when for the first time since the 1930s, a substantial devaluation of the local currency occurred. That date marked a point of rupture and the start of an economic crisis that is yet to end.

The ’80s and ’90s were a period of deep crisis and social marginalisation. By the turn of the century, the social conditions most Venezuelans found themselves in were alarming.

These are the social conditions out of which the pro-poor Bolivarian Revolution lead by former president Hugo Chávez emerged in the late ’90s...

Yes, the Bolivarian Revolution emerged above all with a proposal to invest Venezuela’s oil income in alleviating people’s needs and then transform Venezuela’s economy and its role within world capitalism.

It is worth noting that every Venezuelan government since the 1930s has had its own project for “Sowing Oil”. That is, using the external income generated from oil for national development. Some believed the best way to do this was by satisfying human needs, others thought it required a process of forced industrialisation; but all, more or less, had the same idea. The Bolivarian Revolution was no exception.

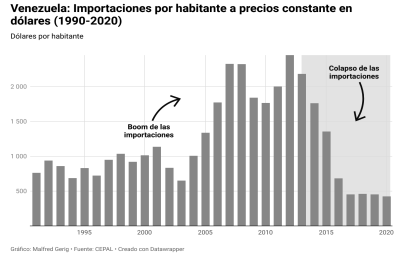

It also has to be said that the Bolivarian Revolution benefited from a period I call the “golden age”, which occurred from 2003-04 to 2012. During these years, two major systemic events occurred, which pushed up oil prices: the War on Terror and the US’ crusade to reshape geopolitics in the Middle East; and the rise of East Asia, in particular the boom in oil demand generated by China’s growth. These two phenomena combined to push oil prices up and briefly paper over the crisis.

But with the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, problems began to emerge in the Bolivarian Revolution’s macroeconomic model. This was followed by another major event that splits this story in two: the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013. His death generated a forced leadership change in the Bolivarian Revolution, amid a rapidly escalating economic crisis specialists knew would require drastic corrections.

Before we start talking about the Maduro government, I would like your opinions on whether economic policy mistakes were made during the Chávez government.

I would say three things about the Chávez government’s economic policy. The first is that its economic policy did not place enough special emphasis on the negative sides of oil. As oil prices began to rise, Chávez was obsessed with the belief that there was nothing pernicious about the country reproducing itself based on international rent. This was the same mistake that other governments made, such as the Andrés Pérez government in the 1970s. Oil is like that: when it is not there, you only see the bad side of it; but when oil prices are high and you can pay for everything or solve everything on the cheap, it becomes more difficult to see the problems.

I would also add two things that were a bad idea to maintain over time: the fixed exchange rate system and the external debt model. From 2002-03, the government adopted a fixed exchange rate system, or administration of foreign exchange, that in real terms was much less malleable than even the dollarisation of the economy. This generated a process of exchange rate overvaluation in which Venezuela had year-on-year inflation rates of about 30%, while the exchange rate remained pegged at a parity of $4.30. This generated a drive towards imports, and a greater demand for international rent to pay for those imports. All this put pressure on productive and industrial sectors to import instead of diversifying their exports.

Of course, there were benefits to the fixed exchange rate system: cheap imports, higher consumption levels, controlled inflation. But the fixed exchange rate system led to a path of dependence that generated economic interests among sectors of the government and business elites, particularly those capitalists involved with imports who ended up benefiting from this system, even though in theory they were the main enemy of Chávez’s project. The result was that Venezuela became even more dependent on oil exports.

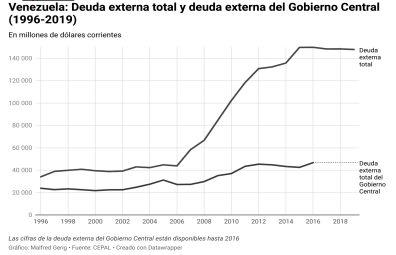

Tied to the fixed exchange rate issue was the issue of external debt. Venezuela had enough inflowing foreign currency that it did not need to raise its external debt. But the government carried out a large-scale and poorly-executed program of external indebtedness, which ended up exploding after Chávez’s death.

This is related to the fixed exchange rate system because this made private foreign debt cheaper. As a result, a whole network of zombie [shell] companies were set up, which borrowed externally and paid that debt with cheap dollars obtained from the fixed exchange rate system. This had drastic repercussions on the national economy.

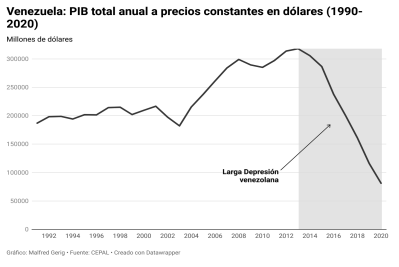

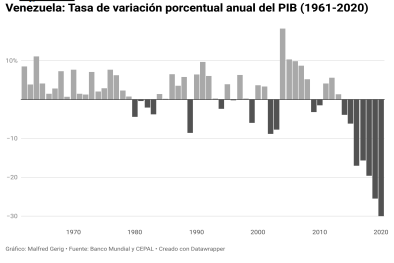

That said, Chávez’s economic policy may have had its problems, but it led to GDP growth between 2004-08, when there was a two-year recession, before again seeing GDP growth until 2013. The 2008 crisis was not easy to solve, but it was solved. There were problems and difficulties; the issue of electricity generation, for example, was a major one. But it was an economic policy that never led to a mega-depression. It was a coherent policy that never excused itself in any way and always provided answers to technical questions. It was a policy where you knew what the figures were and where there was no lack of transparency.

So, when Maduro takes office in 2013, not only had the golden era that paper over the economic crisis ended, but this was now intertwined with a political crisis generated by a leadership change in the Bolivarian Revolution...

As I said, this model was already, as we say in colloquial terms, pasando aceite [dripping oil] since 2010-11. While the Venezuelan economy grew in 2013, investments suffered a shock. This is a key indicator of recession. Then in 2014, the Venezuelan economy went into a recession that ended up transforming into the worst depression ever seen in a Western country that was not at war. The Venezuelan economy shrank by about 80% of GDP. The result of this in social terms is the mass migration we have seen of Venezuelans who have had to leave the country and the levels of subhuman consumption, malnutrition, lost days of schooling and a host of other issues that the vast majority of the population finds itself in.

Then the crisis clearly started before the sanctions imposed by the US?

We have to say two things. First, that this was not a question of bad economic policy, but profoundly serious structural contradictions in the economy. This was not about a bad government coming to power, but a bad government coming to power and having to deal with a very serious and long standing structural crisis.

Second, that the sanctions came on top of both these things — a very bad economic policy and a very serious crisis — and created a perfect storm. Amid this perfect storm, each factor fed off each other, culminating in a nuclear bomb of dispossession, social marginalisation, deteriorating conditions for production, and so on.

The reality is that many things, both political and economic, occurred before the sanctions were imposed. This idea that it was all the fault of the sanctions — which the government has tried to push, above all outside the country because domestically people know it is mainly Maduro government propaganda and blame passing — has gained international traction because it is mixed in with the question of US imperialism.

This is not the same as saying the sanctions are a trivial matter; they are absolutely serious. But when they are used as a weapon by the government to exonerate itself from responsibility for its economic policy and its handling of the crisis — which is largely to blame for this social, economic and political catastrophe — it does a disservice to truth and reality. It is one thing to take the sanctions and the grave social damage they have caused seriously; it is quite another thing to do what the government has done, which is to trivialise the sanctions and use them as an excuse, while in practice doing little about the social impact these sanctions have on suffering humans.

In your opinion, what has the US government sought with its sanctions?

It is worth recalling that the first sanctions started in 2015, but that these sanctions were not remotely comparable to the sanctions implemented in 2019. We have to distinguish between two different sanctions regimes: on the one hand, the comprehensive sanctions regime that starts in 2019; and on the other, the sanctions that came before that as part of a targeted sanctions regime. The targeted sanctions regime pursued a strategy of attrition, while the comprehensive sanctions regime sought a collapse of the Maduro government.

There were a lot of sanctions prior to 2019 targeting top-level government officials over allegations of corruption, economic wrongdoing, and so on. The strategy here was not really about determining whether these public figures were involved in any crime, but to fragment the ruling elite. The US thought: “Here we have economic interests of actors who have investments in the US, who have deep connections to the international monetary system, who need to make transactions, and so on. When we sanction them, this will lead to the government fragmenting.” What happened was absolutely the reverse.

Prior to 2019, the Venezuelan government was also prevented from obtaining fresh currency through loans via sanctions imposed in 2017. However, by then — and contrary to the government’s belief — the problem facing the Venezuelan economy was not one of liquidity but of fundamentals. Any new debt was only ever going to be paid for by consumers and taxpayers, which is what ended up happening.

From 2019 onwards, a comprehensive sanctions regime was imposed, above all through sanctions on [the state oil company] PDVSA and the Central Bank [of Venezuela, BCV]. I have described these sanctions as a “weapon of financial destruction”. This sanctions regime was based on: disconnecting Venezuela from the international banking and SWIFT systems; disconnecting the BCV, and therefore Venezuela’s private banking system, from the international monetary system; and halting trade in strategic goods to limit the inflow of foreign currency. It represented a de facto severing of the country’s ties to the global economy.

It is worth asking why the sanctions implemented in 2019 did not end up causing more damage. The answer is because the Venezuelan economy was already destroyed. Venezuela was already six years into its Long Depression before the comprehensive sanctions regime came in. The comprehensive sanctions regime only came into effect in what I termed the “disaster stage” of the Long Depression, which was its third stage.

I want to return to this question of the different stages of the Long Depression, but before then I want to finish with the issue of the sanctions. What impact did the sanctions have in political terms if they failed to fracture the government or bring it down?

Sanctions had the political impact of changing the regime from within. The comprehensive sanctions regime pushed Venezuela’s rentier capitalism towards a neoliberalism with patrimonialist characteristics and a sui generis Venezuelan oil-based form of crony capitalism. The combination of an economic policy based on orthodox-monetarist measures and a neoliberal spirit — the two things are not the same — led to a regime change from within.

We saw a gradual rise in patrimonialism, which is nothing more than the privatisation of the state by civil servants and administrative cadres. The state becomes a private preserve and the state’s assets and means of administration become a means for civil servants to generate an income. This phenomenon already existed, but when orthodox-monetarist economic measures led to drastic cuts in public sector workers’ income, patrimonialism radically expanded as workers sought to use the tools that the system provided them with to generate an income that the system itself was taking away.

We saw that even the leitmotif of the government changed. This government no longer governs for the same people as the Chávez government. You could say that the Maduro government implemented bad economic policies between 2014-16, but perhaps it did so wanting to govern for the same people that Chávez governed for. But since 2016, and especially since 2018-19, the government no longer governs for the people; instead, the people have been made to carry the burden of the government’s economic policies and its neoliberalism with patrimonialist characteristics.

What has prevailed, especially from 2016 onwards, is capitalist realism. The dominant idea adopted by the ruling elite back then was that there was no other option but to embrace a kind of criollo [local] capitalism that could allow them to stay in power, but now with the support of certain sectors of society that they were historically at odds with, such as local capitalists. Today, Maduro’s government is a government that, to a large extent, has the support of local capitalists. As it lost the support of the people, the government replaced it with the support of these capitalists.

We could therefore say it was not so much a question of the sanctions leading to a loss of support for Maduro, as the sanctions being implemented because Maduro was already losing support....

I agree: Maduro’s loss of popularity was an incentive to implement sanctions. It is not the same to implement sanctions against a government that has strong popular support, as it is to implement them against a government that has faced four years of the worst economic crisis, that is facing a very serious food crisis where Venezuelans had nothing to eat and have to queue for everything, and so on.

The sanctions started in 2015 because that is when the catastrophic stalemate in terms of power started. That year the opposition overwhelmingly won the National Assembly elections. The lack of support for Maduro’s government was clearly exposed.

That is why the government has since applied what [US political scientist] Norbert Lechner calls “the strategy of a consistent minority” by tilting the political playing field in its favour to remain in power. Since 2015 it has gone down an authoritarian path, which has had different facets. This path ultimately led it to the recent elections on 28 July, when the government took this authoritarianism to a new level.

Many on the left believe the sanctions were imposed on the Bolivarian Revolution as some kind of moral punishment. I do not know if that was the case, but if this was true, the best antidote Chávez had against such weapons of moral punishment was maintaining formal and real democracy. He never gave anyone an excuse to implement sanctions or any kind of strategies of geopolitical encirclement and regime collapse.

Why then do you think the US has started to ease sanctions if the government has become even more authoritarian and has even less support?

The answer has to do with the geopolitical effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine [which has pushed up oil prices]. And that the US government is reaping the rewards of these sanctions by having set up an oil exchange program — because the US is not paying for Venezuela’s oil. Under this program, the OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] basically has sovereignty over Venezuela’s oil via remote control.

That is why the US government grants a licence to Chevron, which pays PDVSA with debt forgiveness. In theory, PDVSA receives no fresh currency; what it receives in exchange is a discount on the debt it owes Chevron. There may also be some other benefits for Venezuela; for example, the exchange rate system may benefit from Chevron selling foreign currency in the exchange market as part of its operations in the country.

But in practice, the Venezuelan state’s sovereignty over its oil has been completely suspended. In the past 100 years, the US has never had as much control over Venezuela’s oil as it does right now.

Returning to the Maduro government’s economic policy. You said that by 2018-19, the Maduro government was already clearly a government that no longer governed for the people and referred to three periods within the Long Depression. Could you elaborate on this?

The Long Depression that started in 2013 has three major periods. The first, between 2013-15, is what I call the “period of crisis”. In this period, government economic policy was characterised by inaction: the dominant idea within the government was that there was no crisis and that it could carry on doing the same thing and obtaining the same results.

Initially it even denied there was a crisis, to the point that to talk about questions of technical economic issues, macroeconomics, investment, consumption, etc at the time meant you were a “neoliberal”. Instead, everything was a result of the “economic war” — a conspiracy theory involving everyone from imperialism to the local corner shop owner. There was a complete disregard for questions of basic economics.

This period saw the collapse of the currency exchange market, which generated a very important supply shock to the Venezuelan economy, given its deep dependence on imports. Most of the industrial sectors still active at the time were very dependent on imports. As a result, these sectors contracted.

So, the main characteristics of this period of crisis were a supply shock, the collapse of the exchange rate, and what I call, borrowing from Marx, the impossibility of reconverting money into capital. This was because production was unable to continue at the same scale due to these shocks to the currency market and imports.

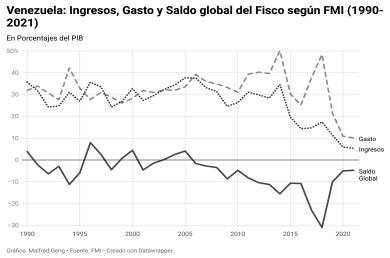

Then we had the oil price shock in 2015. The government once again concocted a conspiracy theory that this was all part of imperialism’s strategy. In reality, it was our partners — OPEC and Saudi Arabia — who sought to keep oil competitive with shale gas. This oil price shock generated what everybody was already expecting: a very serious debt and fiscal crisis in Venezuela.

That is when the first major disastrous economic policy decision was taken: to continue the strategy of paying foreign debt. The government decided to halt imports in order to pay the foreign debt, using the argument that imports meant giving dollars to capitalists to enrich themselves. Sure, to a large extent that was true; but giving dollars to capitalists also means importing food, industrial inputs, etcetera.

As part of this strategy, the government paid US$100 billion in foreign debt. To put that figure in context, at one point Venezuela’s economy was $40 billion; that is, the government paid off an amount of foreign debt twice the size of Venezuela’s economy. The shock that this generated on imports led to a second major supply shock, taking the country’s economic depression to a new level.

This policy also generated another deep shock to production, which pushed Venezuela into a profound humanitarian and food crisis between 2016-17 as agro-industrial and food import sectors totally collapsed. This was the second phase of the Long Depression: the “period of collapse” between 2016-18.

In this phase, the government tried to apply its first chaotic macroeconomic stabilisation program, based on paying foreign debt and cutting imports in order to improve conditions. It was completely naive on the part of the government to think that dressing up to impress international finance would lead to an influx of fresh currency and thus solve the serious structural problems afflicting the Venezuelan economy. Particularly, as I insist, when the problem facing the Venezuelan economy was not one of liquidity but of fundamentals.

The main consequence of this program of being a “good payer” of foreign debt and import cuts was that it became intertwined with a deficit management strategy to facilitate paying foreign debt through the sale of PDVSA debt bonds via the Central Bank. This represented a form of Quantitative Easing (QE) on steroids amid a collapsing economy. It led to one of the worst periods of hyperinflation in Latin America’s history.

This triggered a new phase in the crisis, as GDP began falling by double digits. As with similar experiences in history, this hyperinflation was caused by the debt crisis and political-institutional collapse. With the government still pursuing a strategy of cutting imports to pay debt, Venezuelan households were burdened with the debt payments and their wealth collapsed due to hyperinflation.

This is the third phase, the “period of hyperinflation”, where hyperinflation became a social phenomenon of such harrowing dimensions that people basically forgot all the other economic problems. Hyperinflation absolutely changed society. This is also the period in which the government began, in mid-2018, to implement the orthodox-monetarist program it still maintains.

We cannot even really call it an adjustment program; it is a stabilisation program designed to reduce inflation without taking into account the serious impacts the program would have on economic activity and society.

The program’s main pillar was a draconian cut to public spending, which in 2018 was about 48.4% of GDP, while revenue amounted to 17.4% of GDP, leading to a fiscal deficit of 31%. Under this new program, spending was first reduced by 27 percentage points in 2019, then reduced again to about 10% of GDP in 2020.

This orthodox-monetarist policy also included other pillars, in particular a financial squeeze that sent Venezuelan society back to the financial stone age by implementing a legal reserve requirement on banks that at one point reached 93% of reserves. The aim was to cut off secondary sources of money creation. This meant that the level of household credit in 2019 was only 2.2% of GDP. Amid hyperinflation, households could not even use credit cards to take advantage of negative real interest rates to buy the goods they needed. Companies that wanted to invest or continue producing had to use their own capital as they could not get bank loans.

There was also a very serious wage squeeze, as adjustment programs of this nature require a shock on consumption and demand. This was largely achieved through a wage squeeze, especially in the public sector, which covers administrative staff and civil servants but also pensioners as Venezuela has a public pension system. Pensioners today receive the legal minimum wage, which has hit rock bottom: about $2.30 a month. Destroying wages was a means for solving the government’s fiscal problems on the expenditure side rather than the income side, while also destroying demand amid collapsing supply.

Changes were also implemented to the currency exchange market, leading to a unification of exchange rates. The Maduro government had continued with differential exchange rates for about six years. This meant that if you converted the minimum wage at the official exchange rate, it was equivalent to about $11,000 a month — a complete fantasy. No one knows if people were buying dollars at the official rate, but if they were — which is almost certainly the case — it is not hard to see how this created extravagant conditions for mass looting.

From 2018 onwards, the currency exchange market was liberalised. A regime of inter-bank trading desks and successive micro-devaluations were implemented, leading to a gradual dollarisation of society. As dollarisation rose, society had a currency it could now use as a means for exchange, for storing value and as an accounting unit. The bolivar today only functions as a means of exchange, it no longer serves the other two functions that all other currencies have. Prices are marked in dollars because that is the currency that functions as the unit for accounting for all economic activities: for the family when calculating its weekly or monthly expenses; for a large company, etc.

Aspects of this program provided some economic breathing space, but only because the economy had shrunk to such a small scale. By the time this macroeconomic stabilisation program was applied, the economy was much easier to manage. The government could stabilise without any large external financing program, precisely because the economy was so extremely small.

Were there alternative policies that could have been implemented?

There are always alternatives, especially to such a catastrophic policy in terms of impacts on production and society. The government’s policy was basically to activate what Karl Polanyi called “the Satanic Mill” and seek economic stabilisation through social destruction.

In fact, when we seek comparisons to Maduro’s macroeconomic stabilisation program, we see that it most closely resembles the first stabilisation programs implemented in Latin America — in Chile, Uruguay, Argentina — rather than the less orthodox programs implemented in Bolivia or Brazil’s Plan Real. In other words, Maduro’s program is not only more orthodox than the orthodoxy of today but even that of the ’90s.

So, indeed, other things could have been done. The most important of these was understanding that the level of destruction wrecked on the Venezuelan economy had reached such a level that solutions required supply-side economic policies; that is, economic policies that drastically increased investment, generated employment, raised wages, etc.

There were also many alternatives in terms of protecting society from what the government was seeking to do. Instead, society was left to fend for itself because, by that time, all the social assistance programs implemented during the Chávez period and the first years of the Maduro government had been totally dismantled. When the avalanche of social dislocation began, society had nothing with which to protect itself. This is important to stress.

In your book, you argue that this Long Depression has been accompanied by a crisis of government legitimacy. How has the government responded to this crisis?

I characterised this crisis of legitimacy, which above all begins in 2016, as a catastrophic stalemate. That year marks its start because the National Assembly is very important for economic governance. But the strategy of the incoming National Assembly — in their own words — was to remove the president within six months. In response, the government sought to protect itself and govern without the National Assembly.

This led the government down an authoritarian path with different phases, up until the July 28 presidential elections when it took it to another level. Since 2016, Maduro’s government has progressively adopted what Max Weber called a “politics of power for power’s sake”; that is, it abandoned its historical project and the social support base that it governed for and became a government of cliques, a government whose sole purpose was to stay in power.

However, it is important to reject any moralistic reading according to which there are good guys and bad guys in this story. Since 2016, the formal set of rules of Venezuelan democracy have been de facto broken by both sides: the government and the opposition have consecutively attacked this set of rules, in a process by which each move by one side only ever led to a further escalation of attacks against not only the rules of representative democracy, but more importantly protagonist democracy.

The formal hollowing out of popular sovereignty that took place in the July 28 presidential election really began many years before, when both sides of the political class turned against this sovereignty and against providing solutions for the people amid the crisis.

How then can we characterise the government, in political terms, after the 28 July elections?

I characterised this government as an absolutely patrimonialist government that lacks both popular and legal legitimacy, as well as any legitimacy based on legacy. One of the worst political mistakes this government made was to destroy the political capital, or legacy, bequeathed to it by Chávez, precisely because it opted to govern for another sector of society: mainly themselves.

It is a completely authoritarian government with absolutely nothing left-wing about it. It is a government that would love to come to an arrangement such as occurred between [former US secretary of state] Henry Kissenger and [former Egyptian military ruler] Anwar El-Sadat, for example. In fact, it has been seeking this for years, but has failed largely because it continuously places its own obstacles in this path.

There is an idea outside Venezuela that this government represents, to use an old phrase, a “fortress under siege”. That idea is used to legitimise its violation of human, social and economic rights. Such violations are seen as fine because the government remains a besieged fortress supposedly fighting imperialism, at least on the surface.

But this is ridiculous. The Venezuelan people are not an object whose raison d'être is as background actors in some fictitious anti-imperialist storyline. The Venezuelan people are a subject that must be allowed to find a way to express and defend their own interests and sovereignty. This, in my opinion, is the position that the global left must take: above all, taking the side of Venezuela’s dispossessed classes.

We Venezuelans, especially those of us on the left, have been very disappointed with the views of a certain section of the international left. It seems that the suffering of the Venezuelan people, of the families that have had to separate, of the political prisoners, of the people who have had to give up on their life dreams etc, matter little to them amid their completely abstract view of the situation. To simplify the situation in such a way as to believe that there is a left-wing government fighting against imperialism is to sweep under the table all this human suffering. That does not seem ethically correct.

In summary, we have a patrimonialist government that has built a form of crony capitalism, which benefits a social minority based on the dispossession of the majority. It is a government that implements ultra-orthodox economic policies. It is a government pervaded by capitalist realism, according to which there is no alternative to crony capitalism and authoritarianism.

The Bolivarian Revolution under Maduro has become a catastrophe. The Venezuelan people, in line with their republican and national-popular traditions, will no doubt be the ones who resolve this mess. But, today, this government stands opposed to everything good about Venezuela, to our republican traditions and, above all, to our national-popular interests.