A conservative government was established in Japan in October, led by Sanae Takaichi, a right-wing politician from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the country’s first woman president. Taking this opportunity, the Komeito Party, which had been the LDP’s partner for more than 25 years, withdrew from the governing coalition. By a whisker, Takaichi was elected Prime Minister in the Diet’s prime ministerial nomination election after hastily forming an irregular coalition with the neoliberal party, the Nihon Ishin no Kai (Japan Innovation Party).

In this article, we shall refrain from detailing all these twists and turns, or touching upon the historical significance of Japan’s first woman prime minister. Rather, the focus is: how should we politically define the Takaichi administration?

Japan’s left-wing political forces, including the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP), label it “far-right.” What exactly “far-right” means in this context, and how fundamentally it differs from past LDP-Komeito coalition administrations — including the Fumio Kishida and Shigeru Ishiba administrations — which similarly pursued constitutional revision and military expansion, remains unclear. Nevertheless, Japan’s leftists seem satisfied with this characterisation. This view is fundamentally challenged here on the basis of the unique characteristics of postwar Japanese society.

The character of the Takaichi administration

Over thirty years ago I described the transformation of Japanese politics in an authoritarian direction, following the introduction of the single-seat constituency system (at the time referred to, in liberal terms, as “Political Reform”). Rather than using clichés like “fascism” or “a pre-war style restorationist regime,” I described this transformation using the term “imperialist democracy.”

While this type of regime is commonly seen in the old imperialist nations of the Western world, I further qualified it, taking Japan’s postwar uniqueness into account, as “Japanese-style imperialist democracy.” This term did not gain particular traction and was largely forgotten. However, I believe it remains the most fitting expression for the regime concept that is being pursued in Japan today. In my piece from 30 years ago, I characterised “Japanese-style imperialist democracy” as follows.

But what exactly is this “Political Reform”? It is the construction of a political and social system commensurate with Japan’s imperialist economic status. And this political and social system is neither a prewar-style restorationist political system nor fascism. It is a system of Japanese-style imperialist democracy. It is a form of “democracy” established domestically by institutionally and ideologically excluding or marginalizing minorities (political, racial, ethnic, etc.), and internationally by economically, politically, and militarily dominating, suppressing, and exploiting the Third World.

The “Japanese-style” model differs from its European equivalent primarily in that its survival critically depends on the country’s continued subordination to the United States. It also differs from the European welfare-state model of the high-growth era in that the “Japanese-style” is fundamentally neoliberal from the outset. Thirdly, while it resembles the American model in its introduction of an electoral system centered on single-seat constituencies and its pursuit of a capitalist two-party system, it differs from the American model in that, given various power dynamics, it cannot possess the same level of military power and aggressiveness as the United States.

This characterisation remains broadly valid today. Even now, the Takaichi administration aims for some version of imperialist democracy, not fascism or a prewar restorationist regime.

Postwar Japan, thanks to its peace Constitution and the achievements of the postwar democratic and pacifist movements, enjoyed an exceptionally liberal system early on among the advanced capitalist nations. Despite the LDP consistently advocating constitutional revision from the time of its founding, there now remains no prospect of its achievement. Japan’s military still lacks constitutional legitimacy. Since neither the military nor war are legitimised, all associated military activities are significantly constrained (in the prewar era, in contrast, the military’s wishes took precedence over everything).

The right to collective self-defence, though partially sanctioned by the Peace and Security legislation enacted in 2015, has not been fully recognised. Japan’s Self-Defence Forces can only operate abroad within extremely limited scope. Despite the fervent efforts of conservatives and right-wingers, an anti-espionage law has not yet been enacted. Further, intelligence and espionage agencies commonly found in imperialist countries remain, in Japan, merely artisanal entities known as “Public Security Police”.

Rightists have consistently resented these constraints and sought their dismantling; the struggle over them was the postwar axis of confrontation between conservatives (the LDP) and progressives (Communists and Socialists). Even if everything the rightists demand, including constitutional revision, was to be achieved in the future (though this is extremely unlikely under the Takaichi administration), it would merely mean the liquidation of various postwar conditions that prevented Japan from becoming a normal imperialist state. It would not mean a return to the prewar system, nor would it mean the country becoming fascist.

Moreover, the harsh international environment surrounding Japan is not so fragile as to simply allow the intentions of a Japanese administration to be realised. China, now a global superpower, would not permit it; nor would the US, Japan’s greatest ally. Ironically, Japan’s subordination to the US has been both the driving force pushing Japan toward imperialism and a braking force that has contained its development into a truly independent, authentic imperialist power.

The constraints imposed by the Japanese Constitution and postwar democracy (which were both underpinned by a powerful labour movement, peace movement, and various grassroots movements of women and local residents) have become the norm for the postwar left. Consequently, when these constraints disappear, leftists tend to believe that the prewar regime has been revived or that fascism has arrived. In reality, however, their loss merely means the greater realisation of a more normal imperialist democratic regime.

Of course, this does not mean there is no problem. Japan’s Constitution and postwar democratic norms are historic achievements of great struggle. It goes without saying that we must absolutely protect them. However, it is undeniable that, as the strength of the labour movement, and of the Socialists and Communists that have supported these norms has weakened, resistance has also significantly diminished.

If today’s Takaichi administration appears “far right” to our leftists, it is not because it actually is “far right,” but because the left has become so powerless. When we shrink, our opponents appear larger. When we weaken, they seem stronger and more ferocious. Yet, in reality, the LDP itself is also significantly declining.

Sustained decline in Japan’s international status

The decisive difference between the prospects outlined in my piece thirty years ago and Japan’s current situation lies in the fact that Japan’s position in the world has shifted in an unexpected direction during that time. At that time, I believed Japan’s economic growth would continue, and predicted the country would increasingly elevate its imperialist status.

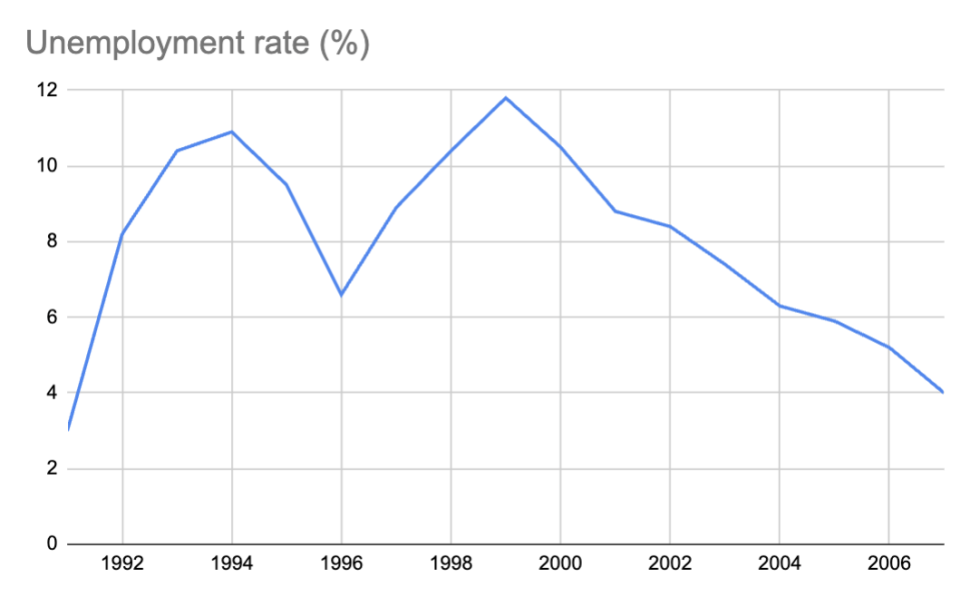

However, what actually followed was the “Lost Three Decades,” during which Japan’s position among imperialist nations declined. This persistent degradation has inevitably slowed the ruling class’s pursuit of a political system befitting Japan’s imperialist ambitions, rendering its realisation incomplete.

Therefore, even if we speak of the same imperialist democracy, what exists today is not one in an ascendant phase, but one in decline. Japan’s subordination to the US shows no signs of improving; rather, it is deepening. Even within the right wing, tendencies toward independent imperialism are scarcely visible.

A proper bourgeois two-party system, where both parties compete in the sophistication of their imperialist democracy, remains far from realised even more than thirty years after the introduction of single-seat constituencies. Moreover, the hegemonic function of the LDP continues to decline. Once-effective coordination between factions within the LDP has gradually become dysfunctional. Consequently, the party has been forced to rely on the personal leadership of a charismatic politician such as Shinzo Abe, but now even Abe is gone from this world.

However, while it is true that the relative strength of rightists and conservatives has increased because the left declined much earlier than the LDP, no clear path to its stable hegemonic restoration is in sight. The LDP government is currently experiencing a temporary resurgence due to the unexpectedly high personal popularity of Takaichi, but this has absolutely no institutional stability.

This is evident from the recent Miyagi gubernatorial election — the first major ruling-opposition showdown after the establishment of the Takaichi administration — where incumbent Governor Yoshihiro Murai, endorsed by Takaichi’s LDP and former coalition partner Komeito, saw his vote share halved compared to four years prior. He secured only a razor-thin victory of 16,000 votes over a newcomer backed solely by the right-wing Sanseito Party.

Imperialist democracy, as previously noted, should be underpinned by a two-party system where conservatives and liberals compete. Ultimately, this system was never realised. Meanwhile, the hegemony of LDP politics has declined and fallen into crisis.

Even in advanced imperialist countries, two-party systems (or equivalent stable systems of alternating governments) are in crisis. In the US, the Republican Party has transformed into a populist party, barely maintaining the two-party system. In Europe, various right-wing populist parties have grown to threaten the dominance of the established major parties. In Britain, the oldest imperialist nation and one of the oldest countries with a two-party system, Reform UK is completely undermining the Conservative-Labour domination.

Therefore, before Japan’s belated imperialist democracy could fully mature and transform into a Western-style model, the old imperialist democracies fell into crisis. With their model to emulate lost, right-wing forces are groping in the dark. The partial return to Japan’s old traditions and its Mikado cult seen among some right-wing forces, such as the Sanseito Party, are merely a reflection of this loss of model rather than representing any real phenomenon.

Japanese conservatism and its neoliberal turn

After 1945, Japanese conservatism lacked a social and political model for postwar Japan. This distinguishes it from US conservatism, which upheld an idealistic vision: the US Constitution as its legal norm, Protestantism as a spiritual pillar, and the democratic world-leading US as its political paradigm. (After all, the US had fought hot wars against fascism as well as Japanese militarism, and, after the war, had fought the Cold War against the Soviet bloc, winning both.) It was a classic, ideal-based conservatism.

In contrast, Japan's postwar conservatism held on through passively accepting the liberal democratic system imposed by the Allied occupation forces, and through overnight transforming its wartime stance that demonised the US into one of extreme support. Consistently hostile to the Japanese Constitution and lacking religious underpinnings, Japan’s postwar conservatism was not an ideal type but a coordinated-interests type. Its view of an ideal society amounted to little more than a slightly modified version of prewar nostalgia for a strong state centred on the Mikado.

This vision was utterly incapable of recruiting a younger generation born and raised after the war. Its ability to maintain governmental power was thanks, above all, to the sustained economic growth made possible by Japan’s integration into the Western bloc under US dominance. Within this framework of subordination to the US and sustained economic growth, conservatives held on to power through skilfully mediated conflicts of interest between social classes, generations, and regions, distributing an ever-expanding economic pie.

On the other hand, postwar progressives, centred on the Socialist Party and the JCP, were the only idealistic political forces in postwar Japan. They presented an idealised vision of a future society modelled on the Socialist Bloc centred on the Soviet Union and China. The global expansion of the Socialist Bloc and the victory of Vietnamese socialism in the Vietnam War fostered a consensus among younger generations that this vision represented the future.

Moreover, even before reaching socialism, the vision of a welfare-oriented, pacifist democratic nation foreshadowed by the progressive local governments established through Socialist-Communist cooperation in major urban areas in Japan offered people a more realistic ideal societal model. Their political rise during Japan’s period of high economic growth stemmed precisely from the enduring vitality of this vision.

However, it did not last long. In 1979, just four years after victory in the Vietnam War, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan deeply wounded the authority of socialism as a model. A decade later, the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe decisively undermined the idealistic model for the postwar left.

Not only the socialist future, but also the more realistic dream of a progressive government centred on Socialists and Communists, became decisively unrealistic. This was due to the successive collapse of socialist local governments in the late 1970s, the Socialist Party’s political drift to the right in the 1980s, and the privatisation of the Japanese National Railways in the mid-1980s, which shattered the backbone of the postwar labour movement.

While the idealist views of postwar progressives crumbled, LDP politics also faced a crisis. The sustained high economic growth that had enabled the LDP’s stable rule had already begun to show signs of decline from the late 1970s. Even so, compared to economic stagnation in Europe and the US, the Japanese economy still appeared solid and powerful. Yet, at the same time, the money politics that had become synonymous with LDP rule was growing increasingly serious. The very mechanism of interest coordination, which had been a fundamental characteristic of postwar conservatism, had become a breeding ground for corruption.

The crisis that unfolded among both progressives and conservatives culminated in the historic period of the first wave of political fluidity in the early 1990s. Most of the new political parties that emerged at this time viewed bureaucratic governance based on interest coordination as the root of all evil. On one hand, they sought to destroy the political system of interest coordination among LDP’s factions by introducing the single-member district system, aiming to create a strong two-party system, and, on the other hand, sought to create a freer market economy by dismantling the economic system of interest coordination between the urban and rural, large capital and small capital, and the strong and weak among citizens.

The collapse of conservative ideals and the rise of identity politics

These two pillars formed the basis of the neoliberal two-party system (“democracy with alternating governments”). This was the first postwar social ideal vision compatible with the postwar system that conservatism ever achieved. Moreover, it was the first comprehensive postwar social model to encompass the majority of political forces from conservatives to liberals, and even many social democrats. Through this, postwar Japan finally seemed to have acquired a new social ideal distinct from restorationism and socialism. Yet this new model soon faded.

Shinshinto (The New Frontier Party), a hodgepodge formed to counter the LDP, failed to achieve the early change of government it had hoped for. Its centrifugal forces caused it to collapse almost immediately, rapidly converging back into the LDP’s one-party dominance. For a time, the Democratic Party appeared poised to become the new major player in a two-party system, replacing the New Frontier Party. Indeed, it finally achieved a change of government in 2009, but this lasted only three years.

What followed was a long-term LDP administration that made the Komeito party an indispensable political complement. Notably, Prime Minister Abe, with his charismatic appeal, went on to set a new record for the longest tenure of any postwar prime minister.

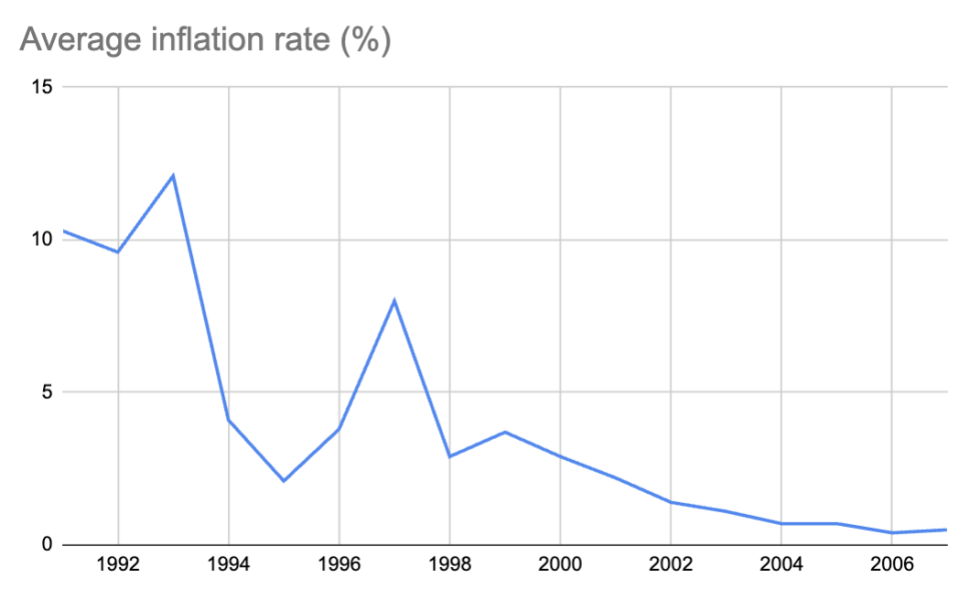

However, despite the implementation of “Abenomics” and unprecedented monetary easing, economic growth failed to materialise. Instead, it produced severe inflation and yen depreciation, further stagnating the Japanese economy and depressing people’s livelihoods. While stock prices soared higher than during the bubble era of the late 1980s, enriching the asset class and institutional investors, the lives of ordinary citizens deteriorated.

Furthermore, citing massive deficits, the tax burden on the public grew ever heavier. The anger of ordinary people toward the Ministry of Finance, which demanded fiscal discipline except for military spending, recently even gave rise to “Dismantle the Ministry of Finance” demonstrations. These were not led by leftists, but rather by rightists. Right-wing segments of the general public and hard-line conservatives had grown disenchanted with the LDP-Komeito coalition government.

Even in the West, the homeland of the neoliberal two-party system model, societies have been torn apart and divided by deepening economic inequality, social unrest over immigration issues, and severe culture wars. They no longer present an ideal societal model for the Japanese people. Instead, they have now become a bad role model for Japan. Even the US, Japan’s senior ally, is overwhelmed by issues beyond immigration: drugs, gun crime, the collapse of healthcare and education, and a rapid rise in homelessness engulfing society as a whole. The situation is similar internationally.

Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the US is now buffeted by threats from a newly ascendant China and Russia, and its position as the world’s leader has significantly diminished. Economically, the US can no longer maintain its position without extracting enormous tributary contributions from advanced capitalist nations such as Japan, South Korea, and the European countries. The once-generous international patron is increasingly becoming a global extortionist.

For conservatives (and for a significant portion of liberals), the neoliberal two-party system model collapsed, replaced by identity politics lacking a concrete vision of society. Idealistic visions of Japanese society with abstract and restorationist overtones, such as “Beautiful and Strong Japan” were brandished once again, leading to the rise of national identity politics centred on the concept of the “true Japanese.”

Meanwhile, among liberals and leftists, equally abstract visions of society — such as “a society where no one is left behind” — are being touted, leading them to become engrossed in anti-discrimination identity politics that absolutises various minorities and individuals’ autonomy.

The rise of this kind of identity politics without a concrete social vision on both sides has led to deep divisions not only between the two political camps but across society as a whole, creating fertile ground for various forms of populism to flourish. The absolutisation of diverse identities without a common class foundation of people’s concrete demands, easily veers toward extremes.

The role of the left

Amid this, the true left must urgently rebuild its front lines and maintain or regain its position as a political force capable of exerting significant influence on the formation of the domestic political landscape. While confronting the various reactionary policies the Takaichi administration will likely promote, it must engage in persistent “war of position”: broadening dialogue with the populace, taking up their livelihood demands from the bottom, and working to realise them. What is needed is not immersion in identity politics, but an upgrade of class politics.

The struggle among the younger generation is particularly decisive. Support for the Takaichi administration and right-wing populism among the younger demographics is not merely due to the influence of social media or political ignorance. It stems fundamentally from the fact that Japanese leftists, greatly aged, exert almost no influence over this generation. But it is this generation that has been hit hardest by the severe impact of the “Lost Three Decades.”

Furthermore, outreach and organising among non-elite women is also important. In Japan, over half of all women workers can secure only low-wage and non-regular employment. This group is relentlessly exposed to a culture of violence and sexual exploitation. This presents fertile ground for the left. Yet, these women are currently turning toward the right. This is because, on one hand, the left is preoccupied with anti-discrimination culture wars, and, on the other hand, the right appears to promise them protection.

Without a revival of the left, Japanese society itself will likely be swallowed up by the chaos of right-wing forces floating without finding a landing point. What this will produce, of course, is not a solid system, such as fascism, but merely the continuation of the “lost xx years” under a chaotic political situation and the further impoverishment of the people. This will form a foundation for a drifting imperialist democracy that grew old before reaching maturity.