We, the (Night) People… Glimpses of Life in the Shadows of TechnoBabylon

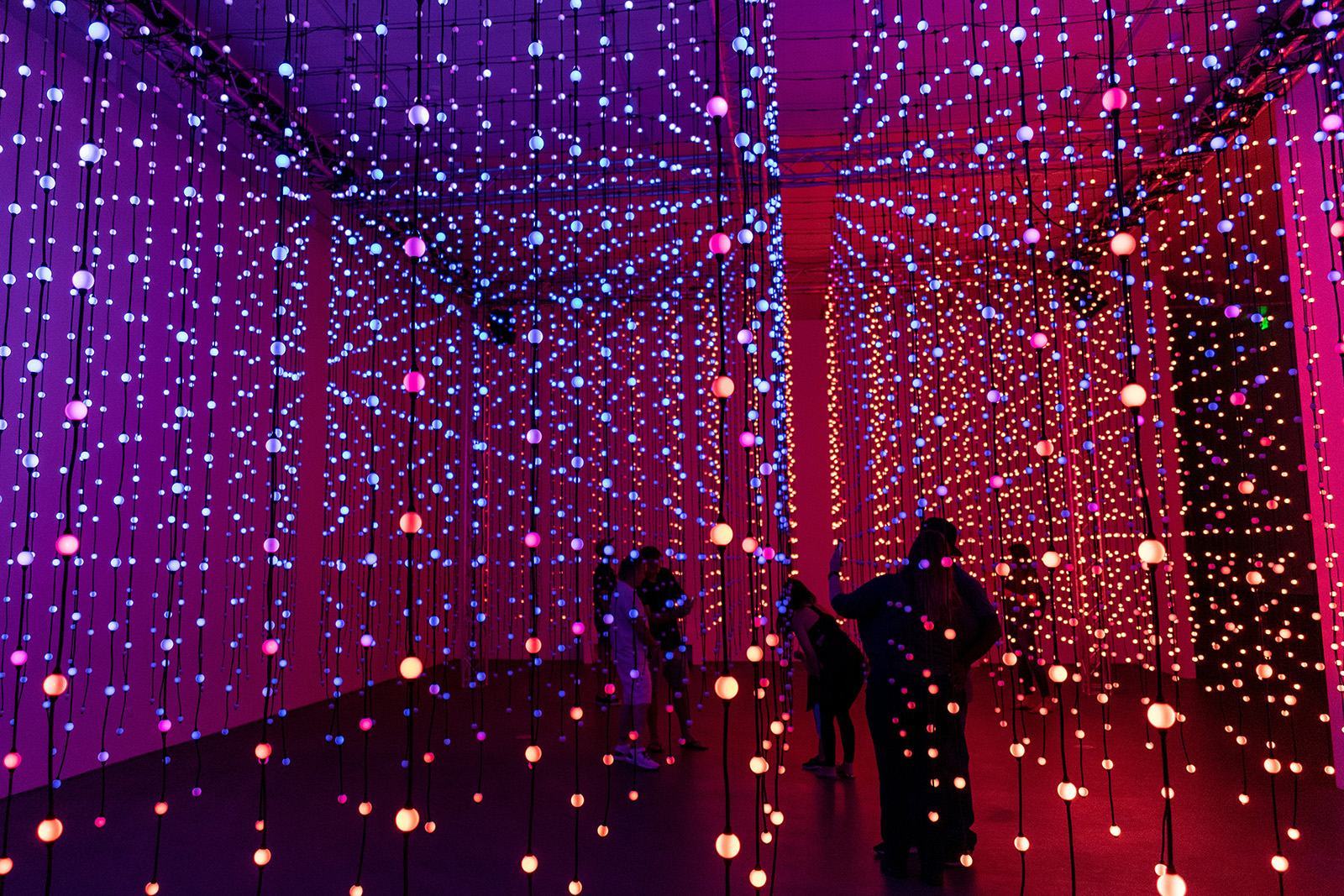

Image by Richard Wang.

“The world you live in is just a sugar-coated topping.”

–Blade (1998)

Since the COVID-19 apocalypse, I’ve worked as a professional road warrior—over five years of sitting in my car on graveyard shifts in lonely industrial areas, packing a pistol and hoping for a boring night.

“Security Officer” is the term I use on those rare occasions when I’m talking to nice, square, middle-class people; I personally prefer “thug-for-hire”—when your job involves the possibility of having to fight street people, foil burglary attempts, or dodge small arms fire, it helps to keep a gleam in the eye and some sense of the romantic. As I once read in a book on professional use of force, you can take yourself seriously, or the job seriously, but never both at the same time.

Working this job has given me a glimpse into certain aspects of our society that the day-walkers never see. Here there be life; here there be monsters.

***

Warehouse buildings where goods are dropped off and picked up, industrial products are manufactured or stored; these are processing centers and supply depots for the things you buy at the store or have installed in your home or business. The workers come and go at all hours; they might finish or begin a shift at three or four in the morning, driving over-sized pick-ups or utility trucks, wearing thick jackets and reflective vests, carrying coolers of food and big thermoses of coffee. The ubiquitous glare of fluorescent lighting casts shadows on the cement and over their faces as they trudge to and from ugly, sterile buildings. These are the hands that move and make the stuff of consumer living.

***

Long-haul truck drivers are an interesting breed. Based on my limited experience interacting with them (they always wanna know if they can park their truck in the red zone to sleep for a few hours before making their deliveries), I’d say many of them are on the autism spectrum. It makes sense; it takes a certain kind of person to spend that many hours alone in a gigantic vehicle, navigating precarious highways, reckless drivers, road hazards, and tedium.

***

Now that I think about it, it takes a certain kind of person to do what I do: alternately sitting in a car or walking around asphalt lots, for nine or twelve or fourteen hours overnight, alone, on constant vigilance for potential danger. It makes sense; out of a profound distrust for institutional authority I would never submit to the testing, but I’ve suspected for years now that I’m on the autism spectrum. It would certainly explain a great deal about my life.

It would also explain why at least half of the e-mail responses I’ve gotten to my Counterpunch articles are from autistic people; something about my writing seems to resonate with folks who are, shall we say, unconventional thinkers.

***

Tow truck companies around here employ a lot of ex-gangbangers and reformed felons. The drivers have many tattoos and few teeth. They work late hours and travel widely through the state, sometimes hundreds of miles from their company headquarters. They enjoy telling stories; like everyone who works in the service field, they deal with a lot of obnoxious behavior, and can’t wait to talk about it.

Sometimes, though, they also get laid by rich trophy wives.

Sounds like slumming to me… but for whom?

***

I’m parked in the driveway of a site on a cul-de-sac when an SUV comes roaring around the corner. It goes to the end of the cul-de-sac and pulls over. A woman in a mini-skirt gets out of the passenger seat and stands next to the vehicle. A man gets out of the driver’s seat, comes around to her side of the vehicle, bends her over and fucks her, then gets back behind the wheel and speeds off, leaving her standing at the curb pulling her skirt down.

She strolls by me but doesn’t look at me; she’s busy on the phone, casually telling someone on the other line that she’s ready to be picked up.

***

These secret corners of the urban wasteland are full of raggedy RVs and the people who live in them. Some of those people are regular citizens—they’re employed, sometimes at multiple jobs, they come and go in work clothes, they keep to themselves—they just can’t afford to pay rent. Thank you, capitalism.

Others are junkies and addicts, petty thieves and hustlers, mentally ill, or some combination of the above. I’ve watched them laugh, argue, scream at each other, make deals, sell dope, walk dogs, ride around on mini-bikes, weld trailers, strike at invisible foes.

Generally, when I’m around, what they don’t do is fight.

***

I’ve always hated the phrase “bleeding heart” as an insult to anyone who demonstrates compassion. That said, it’s clear to me that most liberal-ish, “oh those poor oppressed whoevers” and “get rid of prisons” types have never actually spent much quality time with criminals, crooks, hustlers, hoodlums, and street people. If you’re a middle-class, college-educated, liberal professional reading this, please understand: I spend more time around them than I spend around people like you… And I used to be one of you.

Someone always wants to bum a cigarette or get you to do them a favor or sell you stolen merch or maybe just suck up your energy by filling your ears with gibberish. They’re accustomed to living life in the shark tank, and if they think they can take advantage of you somehow, they will. They might even tell their buddies how nice you are. Now you smell like food.

By the way, twenty-one feet is the minimum safe distance to draw and fire a sidearm before someone can run up on you with a knife and stab you to death. I’ve got a phrase that I’ve added to my lexicon in recent years: That’s Close Enough. I’m relaxed. I’m present. Everything about my tone and body language says that I will not hesitate to drop them if they try to move on me. They understand this language, because it’s the native tongue of the shark tank.

Anything they ask for, I refuse. I ain’t the one.

What I never do is insult them or act like I’m better than them. Even a lowlife deserves basic human respect.

***

I used to have late-night conversations with a guard from another company who worked an adjacent site. He always brought his dog with him to work—a living alarm system. He also had that certain twitch that former heavy meth users get.

He told me he used to bounce at a college bar… where he had to fight people almost every night.

***

A car cruises by, way too slowly. There are at least three people in it, and they glare at me with malicious intent as they pass. Without making a show of it, I draw my weapon, rack a round into the chamber, and put a hand on my car’s door handle. I glare right back at them.

The first thing I do at any new site is scope out nearby objects and structures that can provide cover—that is to say, stop bullets. The plan is: if they jump out, I jump out and take cover, then take aim. The last place you want to be stuck in a shoot-out is inside a vehicle. Most of a car will not stop bullets.

The car with the glaring men leaves and doesn’t return; now I can take the time to notice the sick feeling in my stomach.

***

I was the night relief for the daytime guard, a big, jolly and gregarious dark-skinned brother from Mississippi; put a red stocking cap and a fake white beard on him and he could easily play Santa at the mall in Atlanta. He’s a warm-hearted, funny individual, and he keeps one pistol with a laser sight strapped to his hip, and another in the pocket of his hoodie. “I’m just an old street dude,” he tells me. “I been packin’ a thumper since I was a shorty. I feel naked without it.”

On the job a couple of years ago, he got in a shoot-out with five cars full of armed men… at a site that I’ve worked. He shows me a video on his phone of the car he was driving at the time—the windows are all shattered, there are bullet holes in the front, rear, and side of the vehicle. He got away without a scratch. One of the gunmen wasn’t so lucky.

Even though I’m curious, I don’t ask him how many gun fights he’s been in, or how many people he’s shot. It’s not polite.

***

Last year I saw a man get murdered—shot to death in the middle of an intersection less than a block from where I was posted. Five rounds in quick succession, pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. It took the Oakland police a little over two hours to show up. They roped off the scene, took photos, chatted with each other, then collected the body. One officer walked over to me to take my information and a statement. There was no follow-up. They deal with this kind of thing every day. Life is cheap.

I saw a man get murdered, and afterwards the only feeling I had about it was: better you than me.

If you think that’s insane or horrifying, you’ve probably never spent much quality time with people who live in this world. And you’re definitely not one of us.

***

The next week, at the same site, an RV on the far side of the intersection caught on fire. A propane tank exploded. The fire department arrived in less than five minutes. They had the fire out in ten.

***

Three times I’ve pointed a loaded firearm at someone while working. The people involved never saw it; it was hidden behind my door.

The first time, a beat-up old Honda pulled right up next to my driver’s side door. I’ve never watched anything so intently. A man was driving and a woman was in the passenger seat; both looked like junkies. They said what’s up, then left and didn’t come back. They were probably looking for a quiet place to get high. But it’s also possible that would-be robbers paid them to cruise by and see if the guard on duty was awake and alert. That happens out here. Guards at my company have been robbed.

The second time, it was a well-heeled gay guy cruising for a hook-up. That happens out here. Down-low dudes cruise the long-haul and tow-truck drivers, security guards, and RV dwellers. I kept it professional and told him to leave. He left. Plenty of guards I’ve known would have barked on him like a drill sergeant. Or worse.

The third time, it was some rich asshole in a maroon Tesla who for some reason thought that he could get free parking in my lot, then catch an Uber to the airport. He was the only one who tried to argue with me when I informed him he was trespassing and needed to leave immediately.****

Many of these industrial work sites are haunted. By what, I’m not sure, but I have my suspicions. This entire nightmare of hideous lighting, cement, metal, and plastic is built on the corpse of what was, just a couple centuries ago, a wild and fecund landscape, with an abundance of living beings, including humans, who were killed or driven off in the worst ways. Do you think those spirits are resting easily?

I keep tobacco and white sage in my car; the first to ask their forgiveness, the second to drive the bad ones off.

***

A couple of years ago I was at a re-qualification class for my Exposed Firearm Permit. Before we hit the range, a man came into the meeting room to give a brief presentation on behalf of his security company, which was hiring. The company, founded by ex-cops, paid good wages and benefits to patrol the streets around expensive residential high-rises in San Francisco—rousting beggars and homeless people.

Anyone with a decent moral and ethical core has certain things they will and will not do. I’ll use force to defend myself, but I’ll be damned if I’ll use it to defend the property—and feelings—of wealthy technocrats. They couldn’t pay me enough.

***

Kevlar vests, pepper spray, pistols, and poor wages; RVs, garbage piles, and shitty drugs; cops and robbers, murdered trees, rusted metal, and paved-over lands of destroyed and forgotten tribes.

These are the artifacts of a failed society.

Technology’s Imposition: Violence and “Democracy”

Image by Logan Voss.

Image by Logan Voss.The technology imposed upon us is not free; it entails costs beyond the money we spend on personal purchases or the increase in public-utility bills. It becomes firmly entrenched in our lives before the realization that people are being killed for us to have it takes hold. Just like the piano keys of the 18th century, modern tech gets cleansed of the blood long before we consume the product. And, like the music emanating from that instrument, we become engrossed and distracted with a cool new invention, completely alienated from the process of how we came to acquire it–by violence.

Lay people rarely engage any in-depth discussions about technology even though it is omnipresent in most of our lives in the modern Western world. Supposedly, we live in a democratic society in the U.S.. Yet, the masses don’t have input on the way our society progresses. In fact, we don’t think of it at all. Each generation has different experiences than our parents and grandparents. That’s progress, we’re told. But, what and who are the material drivers of that progress, along with the material circumstances that bring it about? Human society has steadily made improvements on ways of living as part of our evolution as a species. Spinning fiber into string may not seem innovative in our contemporary lives, but at one point it served as revolutionary technology. String allowed humans to create nets, thereby increasing the opportunity to capture more yield when fishing, and feed more people. It allowed people to weave cloth–strips of which at one point in time functioned like currency. The point is that humans always innovate ways to improve our lives. Yet, we now live under a system where–according to some metrics–these can be considered improvements. However, others lead lives that devolve in ways that the beneficiaries of these so-called advancements don’t ever see, or have to consider.

Technological advancement under capitalism is market driven, which means profits over everything, including death and destruction of the natural environment–all flora and fauna. Cristofori invented the piano in the early 18th century, a grand instrument that graced the homes of the elite of the Western world. When the melodic tunes flowed from its soundboard, how many thought about the annual massacre of 75,000 majestic African elephants as their fingers flitted over keys cleansed of the spilled blood it took to create it? The desire for material consumption is promulgated by the ruling class, thereby further entrenching the slaughter required to produce the luxuries of the haves that the have-nots often strive to acquire too–none of which are human necessities, but leave society ensnared in an endless loop of unnecessary, conspicuous consumption.

A Leap Forward?

We are often told of the great transformation at the onset of the Industrial Revolution, fueled by the need to expand capitalist accumulation following the calculus that chattel slavery was a waning profitable means of production. Many new inventions came to market for the masses to experience. There is no explanation of the material circumstances required at the start of the value chain to produce whatever inventive outcomes are imposed on our lives. The advent of electric power in the late 19th century provides the base for other technologies we experience now; street lights, air conditioning, computers, smart phones, etc. Those of us who turn the lights on and off each night never have to think about the mechanisms in place allowing this to happen, specifically minerals extracted from the earth like uranium–used not only to light up our lives, but to create the bombs used to maintain the violence required to collect the ore from the land of others in the first place.

Telecommunications, driven by the need to transmit information quicker to allow capitalists to accumulate more wealth, saw the construction of the fiber optic sea cables that allow masses of people to access the internet right now. Once the first successful cable was laid between New York and London in 1857 to support that quicker communication in the form of the telegraph, the groundwork was laid for continuous advancements. As the mass public was also allowed to make use of telecommunication technology, no one thought of quartz, copper, or germanium (among other minerals) that needed to be mined to build the cables, nor ever consider the entire network residing on the ocean floor–which enters the U.S. via San Francisco in addition to New York. For this network to grow meant setting up a system to constantly extract resources from land outside of the Western world.

Aluminium is a staple on the shelves of modern grocery stores, whether it is the foil rolls used in our kitchens or the soda cans so easily discarded. Aluminum requires bauxite of which the U.S. has almost none. Perhaps the booming steel-mill industry in the U.S. ceased because the iron and manganese required for its production were not readily available in North America, necessitating the extraction of these resources from other lands to sustain the industry. When U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnik made public statements before Congress in defense of tariffs, he stated that, “The issue is you can’t fight a war without steel and aluminum production in America.” Steel manufacturing returning to the U.S. doesn’t resolve the issue of primary ingredients needing to be imported, but, in fact, relies on public ignorance of the steel-making process. It hinges on the masses not understanding that acquiring the ingredients is not based on a fair trading relationship–that tariffs cannot resolve, but military/mercenary violence ensuring capitalists can extract what they need cheaply to maintain their industry profits at the cost of human lives.

Data Centers

The tide of so-labeled Artificial Intelligence (AI) is coming. It’s being imposed. In a democracy, the masses could stop it. Since it’s been decades of back-room dealing in the planning, there’s nothing democratic about its rollout. The emergence of data centers to support AI technology, collectively occupying thousands of acres of land across the U.S., rather than for food or housing, was not something the public had a voice in creating. Knowledge workers in offices are being mandated to integrate AI usage into their work product, presumably to help train that system en masse, and thereby actively participate in the demise of large segments of a future human workforce. Even though we’re told that the servers to maintain AI require exclusively fresh water and consume lots of energy–let alone the earth’s minerals constantly needed to build its infrastructure–the masses have no input on whether we choose to use it. What happens when human populations begin competing with data farms for clean water, a primary human need? Or, when we cannot heat and cool our homes because those data farms consume more energy than the out-of-date U.S. electric grid was designed to deliver? Yet, the building of the data centers to support AI moves forward without prior public knowledge or consent, and with the collusion of elected officials who are in place to conspire with the business community’s profits to the detriment of ordinary people who supposedly voted them into office.

Billionaires such as Bill Gates insist that AI will take over human jobs such as doctors and teachers within the next ten years. (If humans aren’t needed, is that a call to terminate masses of the population capitalism deems surplus?) Yet, in order to have AI replace these jobs, it requires more exploitation of certain human labor to extract the mineral resources from the Global South to support this change. When public policy supports the whims of wealthy oligarchs in control of society’s productive forces without input from the people most impacted, this contributes to social murder–mass premature death. There is no one to hold accountable other than the system of capitalism itself. Constant inventions require resource extraction for the masses to consume to generate wealth for companies that have nothing to do with providing life’s basic requirements of water, food, shelter, etc. The next time one gets excited over the newest advancement, stop to think critically of how it came about, and it won’t seem so nice, but convenient that you are not the one experiencing the violent exploitation at the bottom of the food chain.