How Energy Scarcity Is Reshaping the Global Economy

- Growing inequality reflects deeper physical limits on energy and resource extraction rather than purely financial or policy failures.

- Rising debt and higher interest rates are emerging as binding constraints on governments, businesses, and households alike.

- The 2026 downturn is likely to be uneven, with deflationary pressures, weaker oil demand, and selective regional resilience rather than a single global collapse.

Recently, many people have begun talking about the US having a k-shaped economy. In it, a handful of wealthy people are doing very well financially, while many others are falling further and further behind. I expect that the low wages of the majority of workers will soon lead to adverse impacts on businesses, governments, and international organizations. This phenomenon is likely to lead to a very uneven world economic downturn in 2026.

The world economy is subject to the laws of physics. The world economy seems to be reaching growth limits because there are too few easily extractable energy resources (as well as other resources, such as fresh water), relative to the world’s population. The Maximum Power Principle strongly suggests that even as limits are hit, the world economy cannot be expected to collapse all at once. Instead, the most efficient producers of goods and services will be able to succeed as long as resources are available, while less efficient producers will tend to fall by the wayside. Thus, the Maximum Power Principle somewhat limits the speed of the world’s economic downturn.

In this post, I will try to explain the challenges the world economy is now facing. I will also provide some thoughts on how 2026 will turn out.

[1] The k-shaped economy that the US and many other countries are experiencing is an indication that resources are, in some way, “running short.”

Humans all have similar basic needs. They need food to eat, and they need to cook at least some of this food before they eat it. They tend to need transportation services, both for themselves (to get to work) and for goods, such as the food they eat. They also need governments to keep order and to provide basic services, such as roads and schools. All these goods and services require energy of a suitable kind, such as human labor, burned biomass, or fossil fuel energy. They also require arable land, fresh water, and minerals of many kinds.

If there are not enough resources to go around, the easiest way to accomplish this is by creating a k-shaped economy. One example is with farmland. In many traditions, when a farmer dies, his oldest son inherits the farm. Younger children are then forced to find other kinds of employment, such as being a craftsman, farmer’s helper, or priest in a church. Wages for these younger children can easily fall lower than the income of their land-holding older brothers, especially if large families become common. Creating jobs that pay well for all the younger children becomes a problem.

A similar phenomenon has been happening in many Advanced Economies (US, UK, and other countries included in the OECD) in recent years. Parents are doing quite well financially, but their children often have difficulty finding jobs that pay well, even after advanced schooling. Some adult children are also left with educational debt to repay. This is a new type of k-shaped economy.

[2] The world’s current problem is an ever-rising population paired with resources that are becoming ever-more “expensive” to extract.

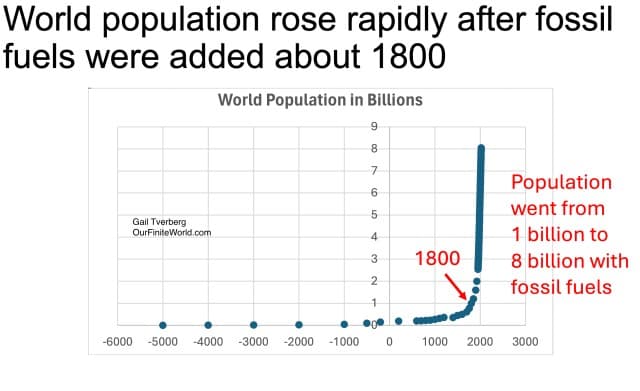

World population has exploded since fossil fuel consumption became abundant. This has allowed more food to be grown, inexpensive transportation of goods and people, and the development of antibiotics and other drugs.

Figure 1. Chart made by Gail Tverberg based on several population sources.

At the same time, the most accessible resources were extracted first. For example, fresh water initially came from streams, lakes, and shallow aquifers. As the population grew and industrial needs became increased, wells had to be dug deeper and aquifers began to be drained. In some places, desalination now needs to be used. Each of these advances in producing fresh water became more resource-intensive. It became increasingly difficult to gather enough fresh water using human labor alone. Instead, increasing quantities of physical materials, energy supplies, and debt were needed to make the new systems work.

The reason debt was needed to purchase capital goods, such as those required to obtain high-cost water, was because the devices purchased were expected to provide the desired output (water, in this case) for a long time in the future. Securing this future benefit required advance funding, using an approach such as debt. The sale of shares of stock, which are expected to appreciate over time and pay dividends, provides a similar benefit to debt.

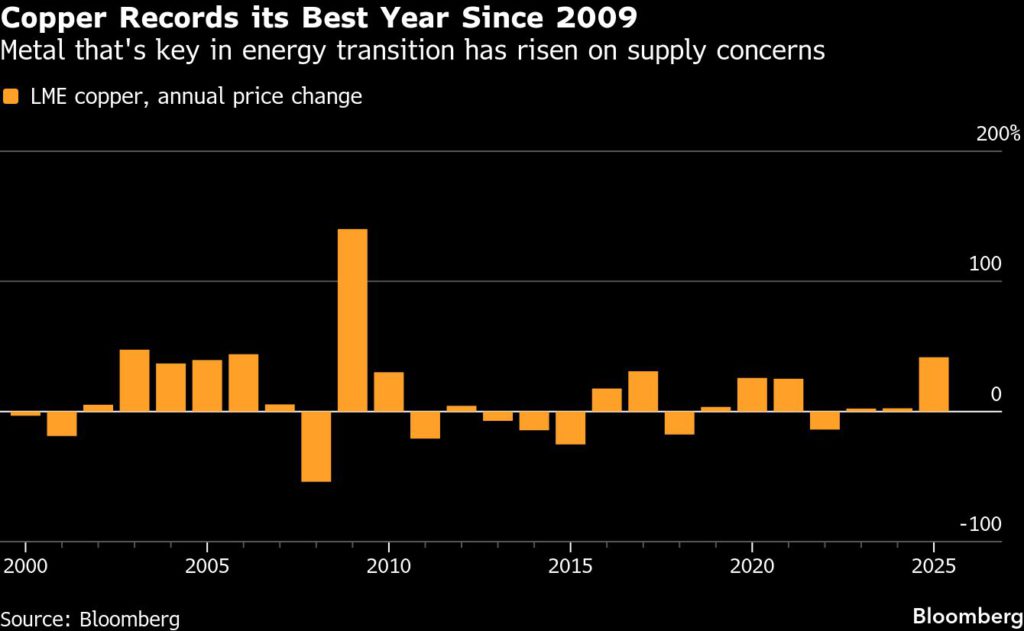

A similar issue arises with the increasing extraction of minerals of many kinds, such as copper, tin, uranium, lithium, coal, and oil. Early on, extraction using manual labor and simple tools was sufficient. However, once the easiest to extract resources were removed, capital goods became necessary to make extraction efficient.

Capital goods, such as coal fired power plants, wind turbines, solar panels, and hydroelectric power plants also allowed electricity to be produced, extending the benefits of fossil fuels. Producing these capital devices requires physical materials and energy supplies, as well as debt or the sale of shares of stock for financing.

[3] A major limit on the system seems to be debt and the interest required on the debt.

In an economy, the growth of inexpensive energy supply acts very much like leavening works in making bread; it greatly helps economic growth. With the increasing use of inexpensive energy supply, vehicles can be made ever-less expensively, compared to using much hand labor for manufacturing (literally, making goods by hand). With this growing efficiency, wages rise faster than inflation. In the 1950s and 1960s, young people found that they could marry and live in nicer homes than their parents. Now, the reverse seems to be happening: many adult children are finding it difficult to keep up with the lifestyles of their parents.

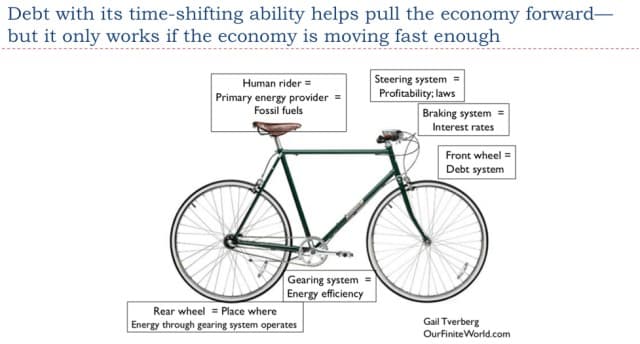

Once the inexpensive-to-extract energy supply is depleted, economies tend to add an increasing amount of debt, in an attempt to pull the economy forward. It seems to me that a major limit on the system comes when an economy slows down so much that it can no longer repay its debt with interest.

Figure 2. The author’s view of the analogy of a speeding upright bicycle and a speeding economy. “Debt with its time-shifting ability helps pull the economy forward, but it only works if the economy is moving fast enough.”

Political leaders like to believe that growing debt, by itself, will pull the economy forward. In fact, this does work, for a time, as long as interest rates are falling. But falling interest rates stopped happening in 2022.

Figure 3. Interest rates on 10-year Treasuries (red) and on 3-month Treasuries (blue), based on data of the Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

Of course, all the added debt contributes to the k-shaped economy. The already wealthy disproportionately benefit from debt payments. They also tend to benefit from dividends on shares of stock and from share price appreciation. The poorer people find that an increasing share of their wages goes to paying interest on debt, especially as interest rates rise.

As debt levels grow, governments eventually have a problem with repayment of debt with interest. They need to raise taxes simply to cover their rising interest payments. This is the reason why Donald Trump wants to get interest rates down. Interest payments are rising rapidly, with near-zero interest rates in the rear-view mirror (Figure 3).

[4] Added technology and economies of scale have been adding to the k-shaped economy.

Technology requires specialization. People with more training and higher skill levels tend to earn more than others. Economies of scale encourage the growth of ever-larger businesses. The people at the top of huge organizations tend to earn more than those at the bottom. Also, as international trade is added, low-wage people in the hierarchy increasingly compete for wages with workers from countries with much lower wage scales. Thus, the wages of less-skilled individuals are increasingly squeezed down.

Furthermore, both added technology and economies of scale require added debt. Again, the interest on this debt (and dividends on stock) disproportionately benefits those who are already wealthy.

[5] In a sense, artificial intelligence (AI) is simply an extension of added technology, with a huge need for electricity, water, and debt.

The hope for AI is that it will make our already k-shaped economy, a great deal more k-shaped. The hope is that AI can eliminate a significant share of jobs, with such high profits that the owners of this technology can become very rich. If it works, the wealth will be even more concentrated at the top than today.

I see the need for electricity, water, and debt as stumbling blocks for AI. I expect that, starting in 2026, the AI rapid growth spurt will seize up because it is already using more resources than are available in some areas. I expect that a significant downshift in AI will adversely affect the US stock market and the rate of growth of the US economy. My hope is that the loss of growth in the AI sphere will not, by itself, bring down the US economy–just nudge it toward recession.

[6] In 2026, with an increasingly k-shaped economy, I expect that world oil prices will drift lower than today.

“Demand” for oil really means “the quantity of oil that people, businesses, and governments around the world can afford to purchase.” As the economy becomes more k-shaped, fewer people can afford to buy vehicles of any kind. Poor people, in the lower part of the k, are hardest hit. They will tend to increasingly rely on low energy approaches, such as ride-sharing, walking, or using a bicycle. They will tend to buy fewer goods that are transported internationally. Governments, as they begin collecting less in tax revenue from the many poorer people, will be inclined to cut back their spending on new buildings and road improvements. These changes work in the direction of reducing oil demand, and thus oil prices.

It is this increasingly k-shaped economy that has been holding world oil prices down in 2025. I expect that prices will drift even lower in 2026 because of the increasingly k-shaped world economy. There aren’t enough very rich people to hold up oil and other resource demand by themselves.

Oil production will not immediately drop in response to these low prices, although it may start drifting lower in 2027. The US Energy Information Administration is forecasting that world oil production will rise by 1.1 million barrels per day in 2025 and by 1.2 million barrels per day in 2026. These amounts do not seem unreasonable based on new developments that have already started producing higher amounts of crude oil.

[7] The heavier types of oil, from which diesel and jet fuel are disproportionately made, are in short supply now. They are likely to continue to be in short supply in 2026.

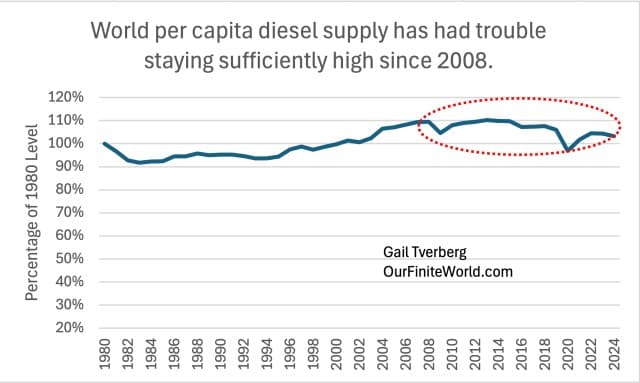

World oil production has risen in recent months. When I investigated, I found that the vast majority of the recent growth seems to be in light oil. Thus, the shortfall in diesel and other heavy fuels is likely to continue as in the recent past.

Figure 4. Chart showing the level of per-capita diesel consumption, relative to the per-capita consumption in 1980. Amounts are based on Diesel/Gasoil amounts shown in the “Oil-Regional Consumption” tab of the 2025 Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the Energy Institute.

This shortage of the heavy types of oil has several impacts:

- With a shortage of heavy oil, a fairly strong country, such as the US, is tempted to attack Venezuela, which has the world’s largest reserves of heavy oil.

- Island nations without their own fossil fuel supplies tend to use a disproportionately large share of diesel and jet fuel, for several reasons: (1) Such islands often burn diesel fuel for electricity. This is an expensive way to make electricity; goods produced with this electricity become too expensive to export. (2) Imports and exports need to be shipped in by boat or by air, again using limited types of fuel supply. Physics tends to push these economies down by making their products expensive to sell elsewhere. Examples of islands with these problems include Cuba, Puerto Rico, Madagascar, and Sri Lanka. Such places tend to be adversely affected by shortages of heavy oil sooner than other locations.

- Without enough jet fuel, long distance tourism is likely to be reduced in 2026. One issue is the lack of jet fuel for flying planes. Another issue is that an increasing share of the population will not be able to afford long-distance tourism because of the k-shaped economy.

- Tariffs are a way of discouraging the shipping of goods long distance, to indirectly save on heavy oil. We should not be surprised by their increasing usage.

[8] In my view, deflation is a greater risk than inflation in 2026.

With a k-shaped economy, demand for apartments (especially smaller ones) tends to stay low. As an economy becomes increasingly k-shaped, low-paid workers tend to share an apartment with one or more friends or move in with family members to save money. In a December 23 report, Apartment Advisor writes that the US average asking rent for studio apartments fell by 2.81% in 2025 compared to 2024. The similar comparison for one-bedroom apartments showed a price drop of 1.72% in 2025. In an increasingly k-shaped economy, I would expect this trend toward lower rental prices of smaller apartments to continue and perhaps become more pronounced.

Real estate selling prices may also be an area for downward price pressure. Young people who have not built up equity through prior home ownership tend to find themselves shut out from buying homes. Also, commercial real estate of many kinds seems to be grossly oversupplied in many areas. Given this situation, downward price adjustments seem likely.

Underlying this downward pressure on prices may be some actual cuts in wages. One law firm reports that cuts in wages are becoming increasingly common, especially for employees of smaller companies.

There are precedents for deflation becoming a problem. The US had problems with deflation at the time of the Great Depression. Japan had problems with deflation after its crash in real estate prices in the 1990s, and China (with its real estate price crash) has recently been having problems with deflation.

[9] “Bread and circuses” become more important as the economy becomes more k-shaped.

Many readers have heard about bread and circuses. Before the Roman Empire collapsed, it used bread and circuses to keep its citizens from rioting from a lack of food. The way to prevent food riots is by making sure everyone has enough to eat through food distribution programs, described as “bread.” Providing circuses offers a distraction from the fact that there are not enough well-paying jobs to go around.

Today, with our increasingly k-shaped economies, leaders have figured out that meeting citizens’ basic needs is essential if unrest is to be avoided. Political leaders somehow need to provide food and healthcare to their poorer citizens. They also need to keep people distracted with entertainment. For many years, governments of Advanced Economies have been trying to provide the equivalent of bread and circuses. In the US, legislation providing Social Security for the elderly was enacted in 1935, during the Great Depression. Many other financial support programs have been added over the years. Today’s circuses today are provided through televised entertainment and video games.

A major problem is that the costs of these programs have become more expensive than tax revenue can support. This is especially true of the cost of “bread,” if its cost is defined as including healthcare and pensions for the elderly, in addition to food. Ultimately, these high-cost programs can bring an economy down. The high cost of bread and circuses is thus a second limiting factor, besides excessive interest payments on government debt, (discussed in Section [3]).

[10] Leaders of many countries are already making plans that can be used to deal with shrinking resources per capita.

If there aren’t enough resources to go around, what can governments do to prevent riots? Two obvious choices come to mind:

(a) Tighten controls on citizens to prevent riots. China has been a leader in this area, and the UK and US seem to be trending in a similar direction. In a sense, the Covid requirements of 2020 were practice with respect to restrictions on movement.

(b) Develop a rationing system that can be used, in case of a shortfall of essential goods. Many countries are looking at central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). These are a digital form of central bank money that is widely available to the public. In the US, I expect CBDCs will be rolled out initially as a way for those who are entitled to food stamps to easily access their benefits. If these digital currencies work, CBDCs can easily be expanded into a widespread rationing system. Government leaders will then be able to decide who can afford to buy what, rather than depending on the way the k-shaped economy currently allocates buying-power.

[11] What lies ahead in 2026?

I don’t think any of us know for certain. The general direction of the world economy seems to be toward contraction, but some parts of the world economy will fare better than others.

Europe looks increasingly like it is an “also-ran” behind the US and China in the world economy. I expect its resource use will continue to shrink back in 2026, indirectly benefiting the United States and the rest of the world. I am hoping that with cutbacks in oil usage by island nations and Europe, and the resulting lower world oil prices, the United States will be able to avoid the worst of the recessionary tendencies looming in 2026.

There are some reports that AI, as it is being applied in China, is providing major success in reducing the cost of coal mining in China. If this is true, it may allow China’s economy to grow in 2026, despite downturns in many other countries.

I am fairly certain that AI, as it is being developed in the US and Europe, cannot continue its recent exponential growth trajectory, and I expect this to become obvious in the next few months. This shift seems likely to pull down US stock market indices. Here again, I am hoping that despite this issue, the US will be able to avoid the worst of the world’s recessionary tendencies.

I don’t expect a world war in 2026. For one thing, no country has adequate ammunition capability. I think civil wars and wars against nearby countries are more likely.

It is possible that the EU will collapse in 2026, leaving the individual countries on their own.

At some point in the future, I expect that the central government of the US will also collapse, in the manner of the Soviet Union in 1991. States will likely regroup and issue new local currencies; the new combined governments will likely provide much more limited benefits than the US government provides today.

Many people think that different leadership will change the current trajectory, but I am doubtful about this. Most of the world’s problems are “baked into the cake” by resource shortages and by too high a population relative to resources. Keeping immigration down is one way of trying to keep resources and population in closer balance.

All in all, I expect a very uneven world economic downturn in 2026. Economies will continue to become more k-shaped. Governments will do their best to hide problems from the public. Stock markets will likely not do well in 2026, if they can no longer count on AI for an uplift.

By Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World