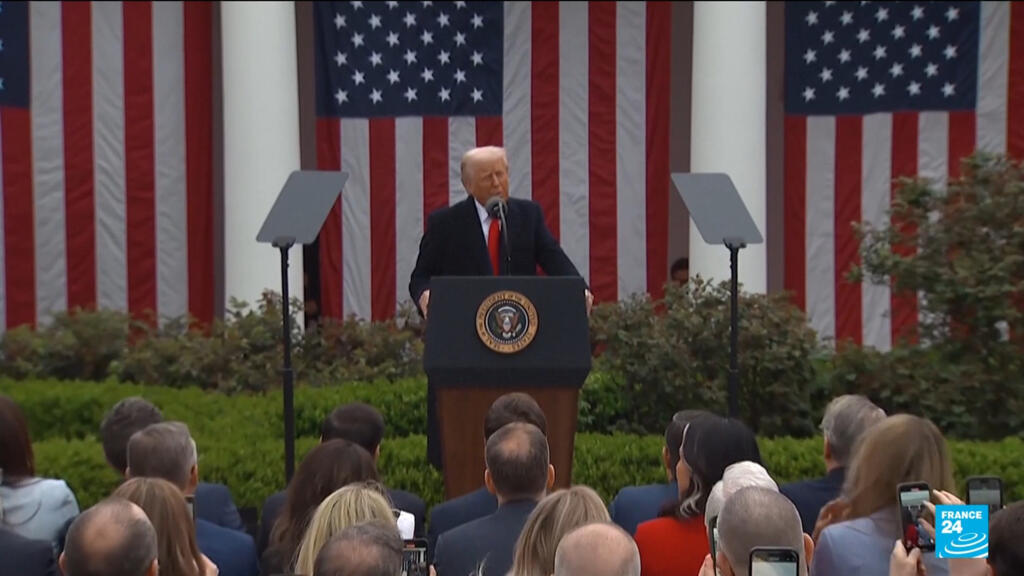

US President Donald Trump signed the charter to formally launch his "Board of Peace" initiative in Davos on Thursday, calling it a "very exciting day, long in the making".

"We're going to have peace in the world," Trump announced. "And we're all stars."

"Just one year ago the world was actually on fire, a lot of people didn't know it," Trump said in his opening speech. Yet "many good things are happening" and the threats around the world "are really calming down," the US president said.

Flanked by leaders of the board's founding member countries — including Argentinian President Javier Milei and Hungarian Premier Viktor Orbán — Trump also praised the work of his administration, "settling eight wars," and added that "a lot of progress" has been made toward ending Russia's all-out war in Ukraine.

He then took a moment to thank the heads of state in attendance. "We are truly honoured by your presence today,” Trump said, stating they were "in most cases very popular leaders, some cases not so popular.”

"In this group I like every single one of them," Trump quipped.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio was next to praise the Board of Peace as “a group of leaders that is about action” and credited Trump for bringing it together.

“He’s not limited by some of the things that have happened in the past, and he’s willing to talk to or engage with anyone in the interest of peace,” Rubio said.

Rubio stressed the body’s job “first and foremost” is “making sure that this peace deal in Gaza becomes enduring.” Then, Rubio said, it can look elsewhere.

With details of the board’s operations still unclear, Rubio described it as a work in progress.

“Many others who are going to join, you know, others either are not in town today or they have to go through some procedure internally in their own countries, in their own country, because of constitutional limitations, but others will join,” Rubio said.

'Most prestigious board ever'

Trump has previously described the newly-formed body as potentially the "most prestigious board ever formed."

The project originated in his 20-point Gaza ceasefire plan endorsed by the UN Security Council but has expanded far beyond its initial mandate.

Approximately 35 nations had committed to joining while 60 received invitations, according to Trump administration officials. The president suggested the board could eventually assume UN functions or render the world body obsolete.

"We have a lot of great people that want to join," Trump said during a Wednesday meeting with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, whose country confirmed membership.

Some leaders required parliamentary approval before committing, while uninvited nations were asking to be included, according to Trump.

Trump also defended inviting Russia's Vladimir Putin — who said he was consulting with "strategic partners" over Moscow's involvement — and strongman figures such as Belarus' Aliaksandr Lukashenka, saying he wanted "everybody" who was powerful and could "get the job done".

Several European allies declined participation. Norway, Sweden and France rejected invitations, with French officials expressing concern that the board might replace the UN as the world's main venue for conflict resolution, while affirming support for the Gaza peace plan itself.

Slovenian Prime Minister Robert Golob said "the time has not yet come to accept the invitation," citing worries the mandate was overly broad and could undermine international order based on the UN Charter, according to STA news agency.

Canada, Ukraine and China had not indicated their positions. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to join on Wednesday.

The UK said it would not sign the treaty at Trump's ceremony over concerns regarding the invitation to Putin, British Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper said.

One billion dollar fee

Countries seeking permanent membership face a $1 billion contribution fee, with Trump designated as permanent chairman even after leaving office, according to a copy of the charter obtained by media outlets. Non-paying members would have a three-year mandate.

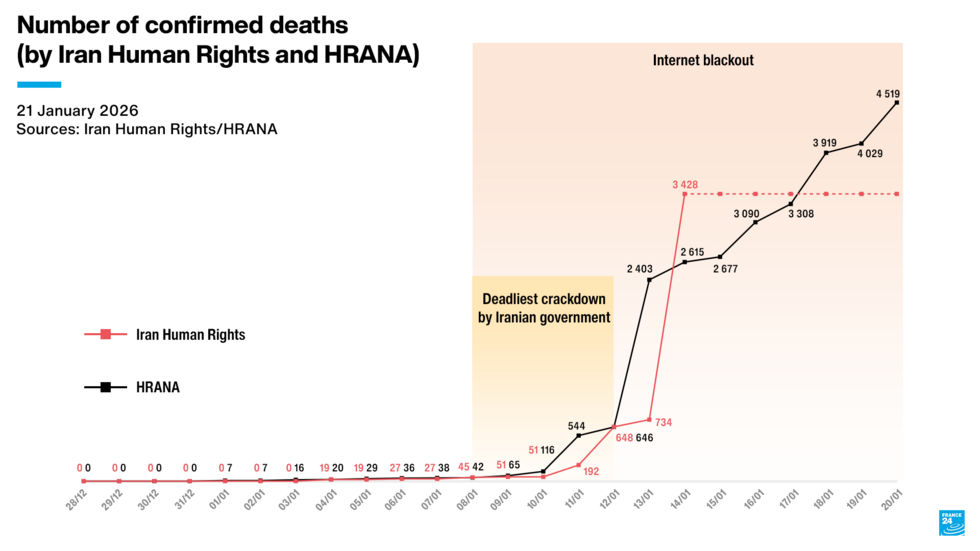

Trump's peace initiative follows threats of military action against Iran this month during violent government crackdowns on large street protests that killed thousands. The president signalled no new strikes after receiving assurances that Tehran would not execute detained protesters.

Trump argued his aggressive Iran approach, including June strikes on nuclear facilities, proved essential for achieving the Israel-Hamas ceasefire. Iran served as Hamas' primary backer, providing hundreds of millions in military aid, weapons, training and financial support over the years.

"If we didn't do that, there was no chance of making peace," Trump said.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrived in Davos on Thursday morning with Trump expressing frustration with both Zelenskyy and Putin over their inability to end the nearly four-year w

"I believe they're at a point now where they can come together and get a deal done," Trump said. "And if they don't, they're stupid — that goes for both of them."

Donald Trump’s ‘board of peace’ looks like a privatised UN with one shareholder: the US president

The US president claims to have ended eight wars. Steve Travelguide/Alamy Live News

January 21, 2026

THE CONVERSATION

It is hard to believe that Donald Trump has only been back in the White House for a year. His accomplishments are many – but most of them are of questionable durability or benefit, including for the United States.

Even his UN-endorsed 20-point ceasefire and transition plan for Gaza released on September 29 2025 is now in danger of being subsumed in yet another grandiose fantasy of the American president: the so-called “board of peace” to be chaired by Trump.

This group of international dignitaries was originally intended to oversee the work of a more technical committee, comprising technocrats responsible for the day-to-day recovery and rebuilding of Gaza. But the board of peace’s charter makes no mention of Gaza at all.

Instead, its opening sentence declares that “durable peace requires pragmatic judgment, common-sense solutions, and the courage to depart from approaches and institutions that have too often failed”.

To make this break with such an unseemly past, the board of peace proclaims itself to be “an international organization” to “secure enduring peace in areas affected or threatened by conflict” and commits to conducting its operations “in accordance with international law”.

To which the immediate reaction is that unilateralism is increasingly the hallmark of Trump’s second administration. Settling conflicts is the prerogative of the UN. And, over the past year, the US has shown itself to be unconcerned about international law.

Membership of the board is by invitation from the chairman: Donald Trump – who has broad and flexible discretion on how long he will serve for and who will replace him when he does decide to go. Those invited can join for free for three years and buy themselves a permanent seat at the table for US$1 billion (£740 million) – in cash, payable in the first year.

With Trump retaining significant power over the direction of the board and many of its decisions it is not clear what US$1 billion would exactly buy the permanent members of the board – except perhaps a chance to ingratiate themselves with Trump.

There is no question that established institutions have often failed to achieve durable peace. Among such institutions, the UN has been a favourite target for Trump’s criticism and disdain, as evident in a recent directive to cease participating in and funding 31 UN organisations. Among them were the peace-building commission and the peace-building fund, as well as office of the special representative for children in armed conflict.

Is this the end for the United Nations?

The deeper and more tragic irony in this is threefold. First, there is strong evidence that the UN is effective as peace builder, especially after civil war, and that UN peacekeeping does work to keep the peace.

Second, there is no question that the UN does not always succeed in its efforts to achieve peace. But this is as much, if not more often, the fault of its member states.

There’s a long history of UN member states blocking security council resolutions, providing only weak mandates or cutting short the duration of UN missions. They have also obstructed operations on the ground, as is evident in the protracted crisis in Sudan, where the UN endlessly debates human suffering but lacks most of the funds to alleviate it.

Third, even though he is unlikely to ever admit it publicly, Trump by now has surely found out for himself that making peace is neither easy nor straightforward despite his claim to have solved eight conflicts.

And the more so if the “pragmatic judgement” and “commonsense solutions” that the charter to his board of peace subscribe to end up being, as seems likely, little more than a thin disguise for highly transactional deals designed to prioritise profitable returns for an America-first agenda.

The charter of the board of peace says nothing about Gaza.

\Omar Ashtawy apa

Part of the reason why the UN has success as a peacemaker and peacebuilder is the fact that it is still seen as relatively legitimate. This is something that is unlikely to be immediately associated with Trump or his board of peace if it ever takes off.

Such scepticism appears well founded, particularly considering that among the invitees to join the board is the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, who is not particularly well known for his love of peace. Even Trump, on rare occasions, admittedly, seems to have come to this realisation. But it did not stop him from inviting Putin to join the board of peace.

What’s in it for Trump?

So, what to make of it all? Is it just another of Trump’s controversial initiatives that he hopes might eventually earn him the Nobel peace prize after all? Is it merely a money-making opportunity for Trump personally, or is it designed for his political and corporate allies, who might benefit from projects implemented by his board of peace? Ultimately, it might be any of these.

The real question needs to be about the consequences for the current system. What Trump is effectively proposing is to set up a corporate version of the UN, controlled and run by him. That he is capable of such a proposal should not come as a shock after 12 months of Trump 2.0.

More surprising is the notion that other political leaders will support it. This is one of the few opportunities they have to stop him in his tracks. It would not be a cost-free response, as the French president, Emmanuel Macron, has found when he did not appear sufficiently enthusiastic and Trump threatened the immediate imposition of 200% tariffs on French wine.

But more leaders should consider whether they really want to be Trump’s willing executioners when it comes to the UN and instead imagine, to paraphrase a well-known anti-war slogan, what would happen if Trump “gave a board of peace and no one came?”

Author

Stefan Wolff

Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

Disclosure statement

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK and a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London.