False information fuels fear during disease outbreaks: there is an antidote

February 9, 2020

The spread of false information can have a devastating impact on affected communities. Woohae Cho/Getty Images

The spread of false information can have a devastating impact on affected communities. Woohae Cho/Getty Images

False allegations and rumours about the coronavirus outbreak have been running riot on social media and in some mainstream media. Misinformation is rampant and conspiracy theories have added to the confusion. Examples include reports that the virus can kill a person in seconds, that Ghana has developed a successful vaccine and that HIV drugs have been used as a cure. There has even been a photo showing dozens of coronavirus victims lying dead in the streets of Wuhan in China.

All of these claims have been shown to be false.

The spread of rumours and plain lies has happened in the wake of other disease outbreaks. For example, when Ebola broke out in West Africa in 2014, rumours about the source of the disease included that the virus was cultivated and released to kill Africans. During the 2018 outbreak of the bat-borne Nipah Virus in India, it was alleged that news of the disease was a corporate conspiracy to boost sales of mosquito repellent.

This sensationalist and alarming content is spread via online channels, creating what have become known as “digital pandemics” or “(mis)infodemics”. Their effect is to amplify public anxiety. This can derail official efforts to provide credible information to the public. Misinformation also has devastating consequences for affected communities, such as the current increase in anti-Chinese sentiments.

Several factors fuel the spread of misinformation during outbreaks of infectious diseases. These include fear and the speed of social media. As previous incidents like this have shown, it’s possible to counter the foolishness. But this requires scientists and public health officials to step up to the plate and to proactively use their platforms to convey accurate information.

Fuelling fear

Misinformation spreads fast when people are afraid. A contagious and potentially fatal disease is frightening. This provides the ideal emotionally charged context for rumours to thrive.

People rely on mental shortcuts (or heuristics) when facing complex information, rather than consider everything carefully and critically. This allows them to make instant decisions that are, unfortunately, often wrong.

Scientists need time to study a new disease and test potential treatments, but people may be desperate and impatient. As a result, it’s common for old home remedies and unproven treatments to be revived. One example is the claim that oregano oil can cure the coronavirus. I have personally received a detailed WhatsApp message about how “Biblical oils” such as frankincense can cure any stage of a coronavirus infection.

Ingrained negativity bias means that people love to share bad news. A 2018 study confirms that false news travels farther, faster and more widely than the truth. Scientists ascribe this to the novelty and emotional reactions these messages invoke. This also explains why people are inclined to speculate and spread exaggerated rumours about the perceived dangers of an infectious disease.

New media

Editors and journalists no longer control the flow of news and opinion. Anyone can generate and distribute text, images, sound clips and video on social media. It’s easy, fast and virtually free to distribute information. Messages can be amplified, shared and reacted to at levels previously unimaginable.

Social media channels provide near-perfect vectors for misinformation to proliferate. Some social media tech giants claim that they are doing what they can to stop the spread of half-truths and outright falsehoods about the coronavirus. Facebook, for example, has promised to help limit the spread of false information by taking down content containing false claims and conspiracy theories that have been flagged by leading global health organisations and local health authorities.

But sources of misinformation are often unclear and it may seem daunting (or even impossible) to control their spread.

Taking control of the narrative

Research has shown that, during a health crisis, affected communities are eagerly looking for information and able to assimilate positive health messages rapidly.

For their part, most scientists are keen to combat misinformation. They even feel morally obliged to help stem the flow of misinformation, particularly when inaccurate health messages could cause harm to desperate and vulnerable people.

Rather than lamenting the dangers of social media, scientists and public health officials should learn how to use social media more effectively for frequent and reliable updates. This could include working with so-called social media influencers including popular sports stars and celebrities to convey accessible and actionable health messages.

The mass media can also play a key role. Major media organisations are rising to the current coronavirus challenge by providing accurate information. Take this visual guide from the BBC and the news updates from the IOL media group in South Africa.

Science media centres, such as the ones in the UK and Australia, have lists of topic experts on hand to ensure journalists can reach them easily. These platforms are providing expert responses to the coronavirus and extensive multimedia resources that help journalists report the story more accurately.

Institutional media offices, science academies and learned societies could play a significant role in mobilising experts to respond visibly and pro-actively during disease outbreaks. For example, many universities such as Harvard and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine are providing updates.

International, national and regional public health organisations share the responsibility to provide accurate and timely information to the media and the public. For example, the World Health Organisation (WHO) provides basic advice to the public and has a team of risk communication experts and social media teams. The WHO also issues daily situation reports and hosts press briefings.

And people are being called on to judge online sources more critically so that they will be able to distinguish between credible and dubious content. For example, the International Federation of Library Associations created an infographic with eight simple steps on how to spot fake news.

There are a number of a number of additional challenges that pertain to Africa. A report on South Africa identified a few of these. They include getting accurate information to people who aren’t literate or don’t have internet access; constructive involvement of traditional healers; making health messages available in indigenous languages and empowering public health officials to communicate accurately, clearly and speedily. All are relevant to other countries on the continent.

Author

Marina Joubert

Science Communication Researcher, Stellenbosch University

Disclosure statement

Marina Joubert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Stellenbosch University provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

Combating medical misinformation and disinformation amid coronavirus outbreak in Southeast Asia

The spread of false information can have a devastating impact on affected communities. Woohae Cho/Getty Images

The spread of false information can have a devastating impact on affected communities. Woohae Cho/Getty ImagesFalse allegations and rumours about the coronavirus outbreak have been running riot on social media and in some mainstream media. Misinformation is rampant and conspiracy theories have added to the confusion. Examples include reports that the virus can kill a person in seconds, that Ghana has developed a successful vaccine and that HIV drugs have been used as a cure. There has even been a photo showing dozens of coronavirus victims lying dead in the streets of Wuhan in China.

All of these claims have been shown to be false.

The spread of rumours and plain lies has happened in the wake of other disease outbreaks. For example, when Ebola broke out in West Africa in 2014, rumours about the source of the disease included that the virus was cultivated and released to kill Africans. During the 2018 outbreak of the bat-borne Nipah Virus in India, it was alleged that news of the disease was a corporate conspiracy to boost sales of mosquito repellent.

This sensationalist and alarming content is spread via online channels, creating what have become known as “digital pandemics” or “(mis)infodemics”. Their effect is to amplify public anxiety. This can derail official efforts to provide credible information to the public. Misinformation also has devastating consequences for affected communities, such as the current increase in anti-Chinese sentiments.

Several factors fuel the spread of misinformation during outbreaks of infectious diseases. These include fear and the speed of social media. As previous incidents like this have shown, it’s possible to counter the foolishness. But this requires scientists and public health officials to step up to the plate and to proactively use their platforms to convey accurate information.

Fuelling fear

Misinformation spreads fast when people are afraid. A contagious and potentially fatal disease is frightening. This provides the ideal emotionally charged context for rumours to thrive.

People rely on mental shortcuts (or heuristics) when facing complex information, rather than consider everything carefully and critically. This allows them to make instant decisions that are, unfortunately, often wrong.

Scientists need time to study a new disease and test potential treatments, but people may be desperate and impatient. As a result, it’s common for old home remedies and unproven treatments to be revived. One example is the claim that oregano oil can cure the coronavirus. I have personally received a detailed WhatsApp message about how “Biblical oils” such as frankincense can cure any stage of a coronavirus infection.

Ingrained negativity bias means that people love to share bad news. A 2018 study confirms that false news travels farther, faster and more widely than the truth. Scientists ascribe this to the novelty and emotional reactions these messages invoke. This also explains why people are inclined to speculate and spread exaggerated rumours about the perceived dangers of an infectious disease.

New media

Editors and journalists no longer control the flow of news and opinion. Anyone can generate and distribute text, images, sound clips and video on social media. It’s easy, fast and virtually free to distribute information. Messages can be amplified, shared and reacted to at levels previously unimaginable.

Social media channels provide near-perfect vectors for misinformation to proliferate. Some social media tech giants claim that they are doing what they can to stop the spread of half-truths and outright falsehoods about the coronavirus. Facebook, for example, has promised to help limit the spread of false information by taking down content containing false claims and conspiracy theories that have been flagged by leading global health organisations and local health authorities.

But sources of misinformation are often unclear and it may seem daunting (or even impossible) to control their spread.

Taking control of the narrative

Research has shown that, during a health crisis, affected communities are eagerly looking for information and able to assimilate positive health messages rapidly.

For their part, most scientists are keen to combat misinformation. They even feel morally obliged to help stem the flow of misinformation, particularly when inaccurate health messages could cause harm to desperate and vulnerable people.

Rather than lamenting the dangers of social media, scientists and public health officials should learn how to use social media more effectively for frequent and reliable updates. This could include working with so-called social media influencers including popular sports stars and celebrities to convey accessible and actionable health messages.

The mass media can also play a key role. Major media organisations are rising to the current coronavirus challenge by providing accurate information. Take this visual guide from the BBC and the news updates from the IOL media group in South Africa.

Science media centres, such as the ones in the UK and Australia, have lists of topic experts on hand to ensure journalists can reach them easily. These platforms are providing expert responses to the coronavirus and extensive multimedia resources that help journalists report the story more accurately.

Institutional media offices, science academies and learned societies could play a significant role in mobilising experts to respond visibly and pro-actively during disease outbreaks. For example, many universities such as Harvard and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine are providing updates.

International, national and regional public health organisations share the responsibility to provide accurate and timely information to the media and the public. For example, the World Health Organisation (WHO) provides basic advice to the public and has a team of risk communication experts and social media teams. The WHO also issues daily situation reports and hosts press briefings.

And people are being called on to judge online sources more critically so that they will be able to distinguish between credible and dubious content. For example, the International Federation of Library Associations created an infographic with eight simple steps on how to spot fake news.

There are a number of a number of additional challenges that pertain to Africa. A report on South Africa identified a few of these. They include getting accurate information to people who aren’t literate or don’t have internet access; constructive involvement of traditional healers; making health messages available in indigenous languages and empowering public health officials to communicate accurately, clearly and speedily. All are relevant to other countries on the continent.

Author

Marina Joubert

Science Communication Researcher, Stellenbosch University

Disclosure statement

Marina Joubert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Stellenbosch University provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

Combating medical misinformation and disinformation amid coronavirus outbreak in Southeast Asia

February 8, 2020

Author

Author

The overwhelming sharing of fake news amid coronavirus outbreak across the globe raised concerns among governments, including in the Southeast Asian region.

In the past weeks, we have quickly found disinformation and misinformation on social media stirring public discussion and, at times, leading to unnecessary panic.

In Malaysia, misinformation claiming that coronavirus would make people behave like zombies raised concerns among medical professionals after a video went viral on Facebook.

In Indonesia, dozens of hoaxes shared on the Internet include inaccurate allegations that some patients in the country had died after being affected by the pathogen.

The new strain of coronavirus, originated from Wuhan, China, spread rapidly across the world, thanks to globalisation.

In less than two months since the first case reported in Wuhan, the virus claimed the lives of over 700 people with more than 34,000 confirmed cases.

However, we know little about the novel coronavirus except that it is lethal if not treated properly.

This uncertainty is causing speculation among the public. It is worsened by the irresponsible sharing of unverified information about the disease.

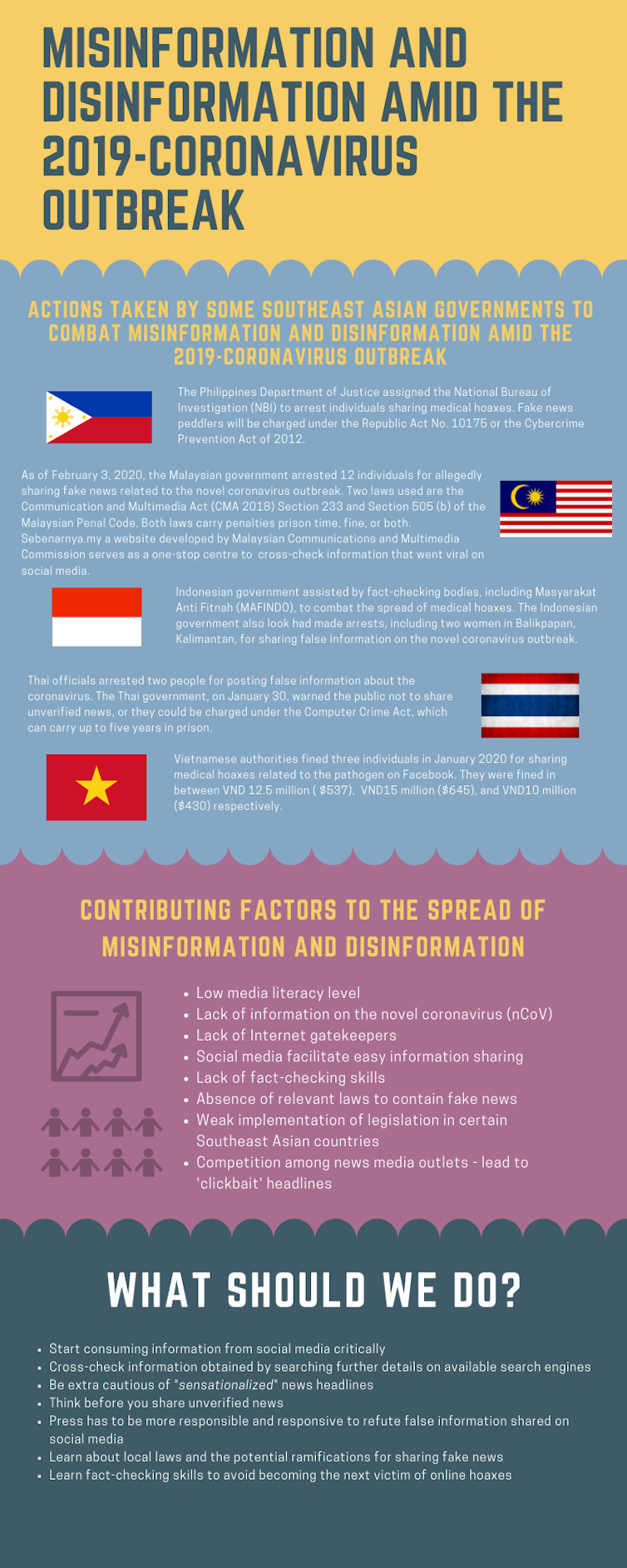

To mitigate the dissemination of medical hoaxes, Southeast Asian governments have taken various approaches.

Fighting against hoaxes

In Indonesia, its Communication and Information Ministry announced that it had found 54 false information about the virus on the Indonesian websites and social media earlier this month.

The Indonesian government has worked closely with fact-checking bodies, including the anti-slander society (MAFINDO), to combat this misinformation.

Having no fact-checking bodies, Malaysian authorities are working together with the media to provide reliable information to the general public.

Government bodies, like Malaysian Media and Communication Council through its website Sebenarnya.my, serve as a one-stop centre to crosscheck information that went viral on social media.

While in the Philippines, the country’s Department of Justice recently tasked its National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) to catch peddlers of medical hoaxes.

Misinformation and disinformation amid the 2019-Coronavirus outbreak. Nuurrianti Jalli

Misinformation and disinformation amid the 2019-Coronavirus outbreak. Nuurrianti JalliHarsher approaches

The severity of information disorder related to the novel virus pushed Southeast Asian government to use stringent body of laws as the distribution of misinformation have caused mass panic.

In Malaysia, for example, the call for a total ban of Chinese tourists emerged fuelled by medical hoaxes consumed through social media.

A similar trend was also found in Indonesia, where anti-Chinese rhetoric exists. Xenophobic treatments against individuals of Chinese descent also happen beyond Southeast Asia amid the outbreak.

In taking serious action against the distribution of hoaxes on the pathogen outbreak, Southeast Asian law enforcers have arrested individuals for allegedly spreading false information on coronavirus.

Malaysian law enforcers have arrested 12 individuals for spreading fake news on coronavirus. If found guilty, they can face up to two years in prison or fine up to RM 50,000 (about US$12,000) or both.

Thai authorities have detained two individuals under the Computer Crime Act. While, Indonesian officials had arrested two women in Balikpapan, East Kalimantan for the same reason.

What’s at stake

a Medical misinformation and disinformation are two components of the information disorder in Southeast Asia and they require immediate governmental attention.

False content ranging from wrong information on vaccines to inaccurate content about the coronavirus demands a proper action plan to be instituted to keep information disorder from worsening.

Although people have associated imposing penalties for spreading fake news with limiting freedom of speech, in medical crises such as this, strict control by authoritative bodies to contain hoaxes are necessary.

Weak control over false content could lead to public panic, and jeopardise efforts placed by the government to control further spread of the virus.

Even despite harsh actions from the governments, misinformation and disinformation could still be easily found in the Southeast Asian Internet sphere.

Social media have undeniably made sharing medical hoaxes easy, worsened by the public’s lack of awareness about the novel virus.

Adding fuel to the fake news fire in Southeast Asia, click-bait headlines by irresponsible media agencies further amplify the spread of misinformation on the new virus outbreak. On social media, people share information without crosschecking their facts and, at times, coupled with xenophobic remarks aimed at China.

Recommendation

Although Southeast Asian governments take various approaches, efforts will go to waste if the public refuse to play their part in containing the further spread of misinformation and disinformation in the public domain.

I would urge the people to always fact check information obtained, particularly ones shared on social media.

The simplest way to crosscheck is to use Google search on the matter and triangulate information from multiple sources.

Scientists across the world are working hard to find the best vaccine to treat the virus, and the public should play a part by acting on recommendations provided by these professionals and not on random posts on the Internet.

---30---

Nuurrianti Jalli

Senior Lecturer at Faculty of Communication and Media Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

Senior Lecturer at Faculty of Communication and Media Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

No comments:

Post a Comment