The impact of orphan wells, both on the environment and on tightening budgets, is a growing concern in the industry.

Boom times result in a vast uptick in wells drilled.

In bust times, when companies disappear, the liability outlook for these probes gets murky and federal and state governments start looking for answers.

August 1, 2021

By Blake Wright

Journal of Petroleum Technology

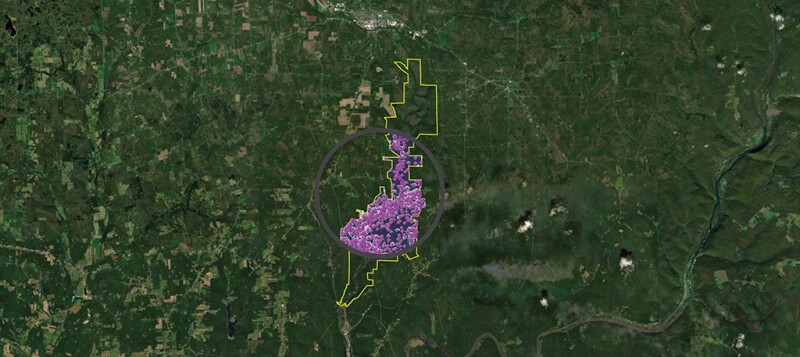

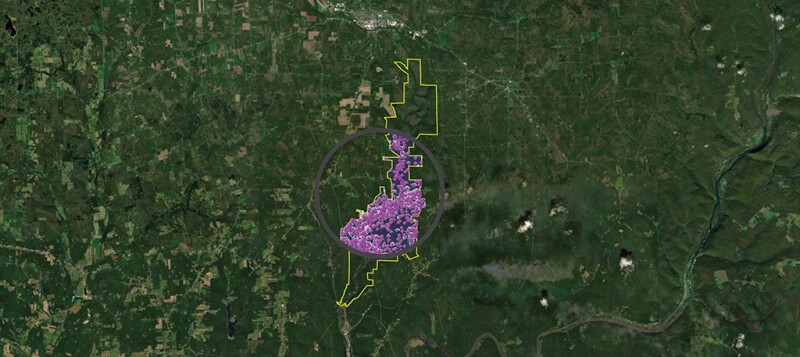

Magnetic surveys are used to guide ground-based field research more effectively. In addition to location data that is not always precise, wells are often difficult to identify in the field due to being buried or concealed by vegetation. Source: National Energy Technology Laboratory.

It’s a problem as old as the industry itself. The initial oil rush in the late 1800s spread like wildfire through Pennsylvania, and by 1891 the state’s annual crude output had hit 31 million barrels, or 58% of the nation’s total oil production for that year. However, by the turn of the century the bloom was off the rose. Pennsylvania’s once-robust oil allure had been eclipsed by finds in Texas, California, and Oklahoma, each spawning its own regional oil booms. So why the history lesson? Because it’s important to understand the potential volume and impact of orphan wells in the US.

In the infancy of the industry, plugging-and-abandonment (P&A) techniques were crude at best, if anyone even went to the trouble. Worse still was the overall record keeping at the time. With oil booms around the country setting off races to harness as much black gold as possible, wells were being drilled at breakneck pace. Once these earliest wells were tapped of their commercial usefulness, operators moved on to the next. There was little-to-no oversight. No regulations. No standards. The result? Thousands, if not more, of scattered, undocumented wells.

“Back in the day, you have people drilling wells, and nobody’s keeping track of where the wells are drilled and who owns the wells,” said Daniel Raimi, fellow with Resource for the Future, an independent institution that conducts environmental, energy, and natural resource research. “The government’s not keeping track and has little to no regulation in place to ensure that operators safely decommission their assets at the end of their lives. As a result, you have wells that maybe produce for a couple of years, and then the owners walk away. Multiply that by a couple of hundred thousand and now you’ve got a problem.”

Today, there is plenty of oversight and regulation for the industry to leave abandoned wells in much better shape than those earliest probes. However, orphan wells are still a problem. To paint the clearest picture, it would be prudent to define what an orphan well is.

This is where we run into our first problem. Definitions can vary wildly from state to state and organization to organization. Some lump all abandoned, unplugged wells into their counts as orphan wells. Others count all idle wells. However, for the sake of clarity we will define orphan wells as those nonproducing, idle wells whose ownership is unknown. By that definition it is safe to say that many of the nation’s earliest wells fit that criteria.

In more modern times, orphans result from idle wells whose owner goes belly-up prior to any P&A work. In most of these cases, bonds are employed to help offset the cost of plugging these wells. However, while they vary state to state, most bonding minimums do not cover the full cost of abandonment and remediation, if needed.

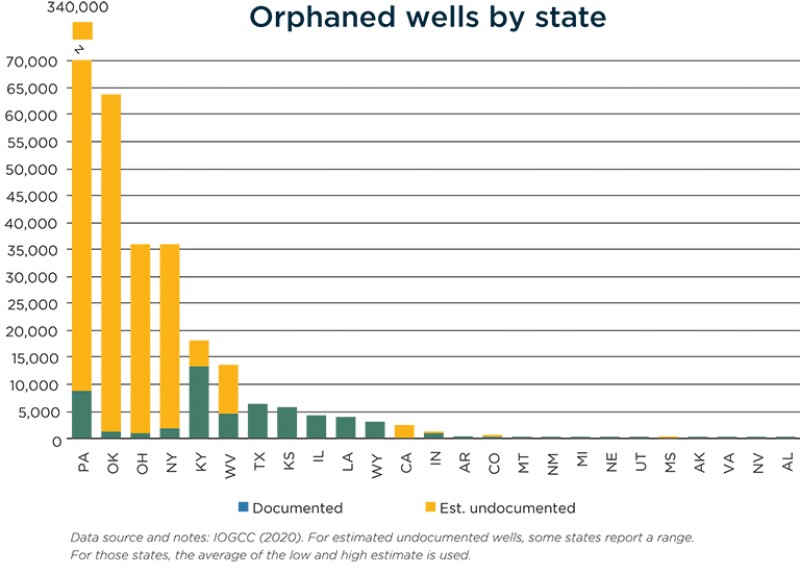

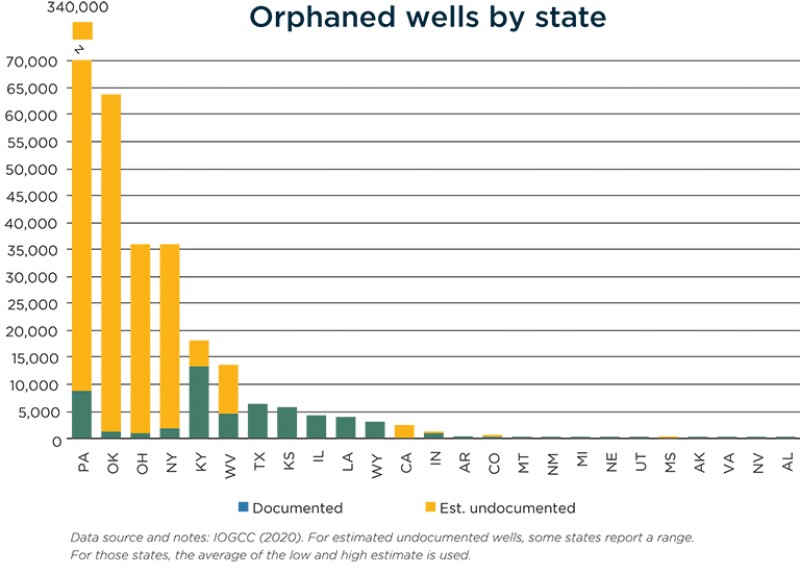

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, there are about 2 million unplugged, abandoned oil and gas wells scattered across the US. Other experts place the number higher; some believe it is lower. Some researchers believe as many as half of those could be orphan wells. A survey by the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission in 2018 put the range of orphaned and idle wells at around 560,000 to 1.1 million. Again, abandoned doesn’t always mean orphaned. One fact that can be extrapolated from the data gathered to date is that no one knows for sure just how many orphaned wells are out there. But that is changing.

Documented and estimated undocumented orphaned oil and gas wells in the US. Source: Columbia University CGEP report.

The Hunt

Researchers like Natalie Pekney have dedicated about a decade’s worth of field work trying to locate, chronicle, and sample the potential hazards from the orphan wells across the US. Pekney is an environmental engineer with the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) who has conducted field work in Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania, her home state and in many ways ground zero for the orphan well issue. She and her team used aerial magnetic survey techniques to pinpoint potential orphan wells by identifying the metal well casings. A 2017 study of the Hillman State Park location, west of Pittsburgh in southwestern Pennsylvania, discovered more magnetic well readings than previously reported in the area’s well count database.

“We started doing this work at least 10 years ago,” said Pekney. “We had a team that was perfecting the approach of using aerial magnetic techniques for finding wells. They would fly the survey and then go out on the ground and check those locations to verify if there was or was not a well there. They were noticing sometimes at these wells they could see bubbling, or you could smell a strong hydrocarbon smell. So just anecdotally, one could assume that some of them were still leaking. Then we had a thought to go out and measure how much, so we’ve been doing the emissions measurements since 2015 or so.”

Over time, the lab released its magnetic well-location technology to the private sector, which now employs sensor-equipped drones for much of the survey work. Now the team focuses more on the methane-emissions work. The group was in the throes of conducting measurement studies in Kentucky when COVID-19 sidelined the effort.

“We’re just now making plans to go back there and try to complete that work,” said Pekney. “The same thing in New York. We had plans to go out there and we had to put those off because of the pandemic. We’re currently trying to start our fieldwork efforts back up now that a lot of the travel restrictions and such have been relaxed.”

Pekney said they really had no expectations of what they might find once they started tracking emissions. With no previously published data on the subject, they had nothing on which to base a guess. Ultimately, in the context of greenhouse gas emissions from all US oil and gas sources, estimated emissions from abandoned wells is but a fraction of the total. The Hillman State Park survey took samples from 31 wells (22 above ground, unplugged and nine buried). The average emissions rate for the aboveground wells was 0.70 kg of CH4 per well per day.

Methane emissions are also a hot topic in political circles. Methane has more the 80-times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere, making it public enemy number one in the fight against climate change and global warming.

“It’s not huge, but at the same time, it’s kind of a correctable problem in a sense because these wells, generally the high-emitting ones have not been plugged, and plugging is effective at eliminating or decreasing emissions,” said Pekney.

Over the course of the next few years, Pekney believes her group can assist states by helping with plugging prioritization—identifying the “super-emitters” and getting those dealt with first.

GPS-enabled computers assist researchers on the ground in finding and geolocating abandoned wells, such as the one pictured here. Source: NETL.

The Answer?

Both state and federal officials have been active in recent months regarding the plugging of orphan wells. Several bills are floating around at the federal level that would aim to put workers sidelined by the pandemic back to work plugging these wells.

Senator Michael Bennet’s (D-CO) The Oil and Gas Bonding Reform and Orphaned Well Remediation Act is aimed at cleaning up tens of thousands of orphaned wells across the nation and reforming the bonding system. The REGROW Act, sponsored by Senators Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) and Kevin Cramer (R-ND) would budget more than $4.6 billion to put skilled energy workers back to work cleaning up these sites, with the goal of plugging every documented orphan well in the country.

“Safety and environmental protection are top priorities for our industry, and we operate under strict standards and practices to ensure that American energy is produced responsibly from start to finish,” said Frank Macchiarola, American Petroleum Institute’s senior vice president of policy, economics, and regulatory affairs. “Our industry complies with all existing state and federal requirements for abandoned wells and reclaiming wells sites, and we will continue to support new efforts, like those outlined in the bipartisan REGROW Act, to plug these wells and further reduce methane emissions.”

Roughly $8 billion has been given out to states by the federal government for mine-reclamation projects over the past four decades. President Joe Biden’s recently announced $2.3-trillion infrastructure plan would earmark $16 billion toward the cleanup and plugging of old oil wells and mines, a significant step up in investment for orphan well remediation.

“Society is bearing a lot of the costs right now because of things like water pollution and methane emissions,” said Raimi. “That is costing all of us something. It’s just difficult to measure. There are some proposals at the federal level to inject dollars into state plugging programs. That’s a helpful first step, but it certainly doesn’t address the magnitude of the problem.

“From my perspective,” he continued, “the thing that would be most helpful is for us to have better information on which wells are most hazardous. Because with, let’s just say, a million orphaned wells, and 2.1 million unplugged abandoned wells, we must prioritize, and we can’t prioritize unless we know which wells pose the most risk to the environment and to public health.”

There is still a long road ahead for the solution to the orphan well problem, and with fresh bankruptcies during the past year due to the pandemic, the number of wells left to deal with continues to be a moving target. The energy transition could be both a sign for celebration and alarm. As assets exchange hands from bigger operators raising capital for greener projects to smaller, lower-cost producers, the new owners will look for every advantage to preserve the bottom line. That might include deferring abandonment work, because, frankly, there’s no money in that.

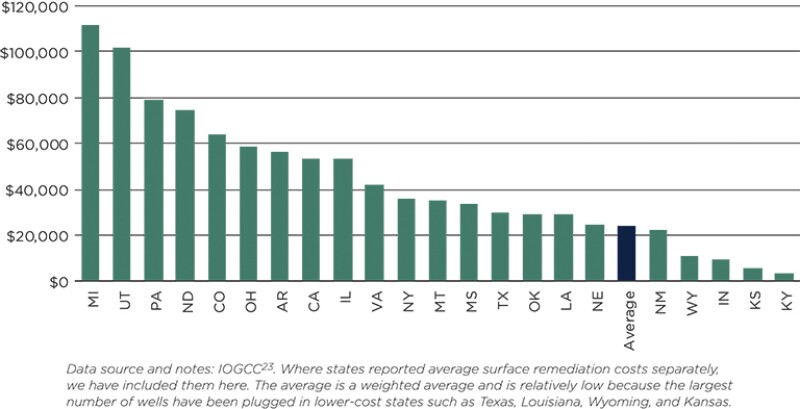

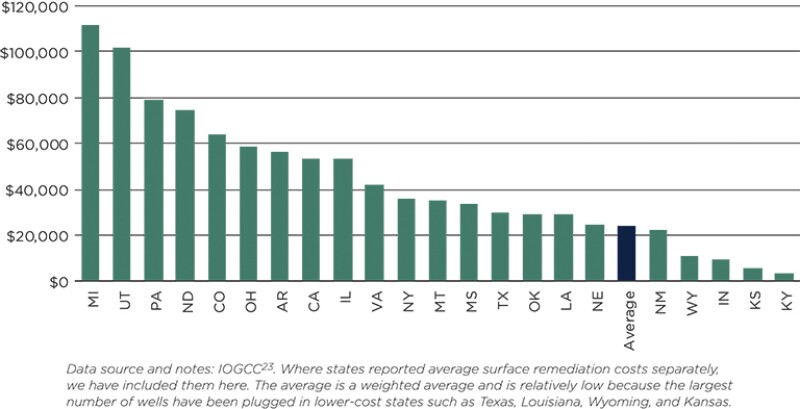

“At the very least, we’re in the tens of billions of dollars range,” said Raimi on the national tab for orphan well cleanup. “I don’t know what the ultimate number is going to be, and therefore we need more information. It’s possible that there are some orphaned wells out there that are not causing anybody any harm. They might be in the middle of prairie land, not leaking any methane, and not causing risk around water. Should we really spend $100,000 to plug a well like that? Probably not. But again, we don’t know which wells pose substantial risks and which don’t.”

Average plugging and restoration costs per well. Source: Columbia University CGEP report.

For Further Reading

Green Stimulus for Oil and Gas Workers: Considering a Major Federal Effort To Plug Orphaned and Abandoned Wells. 2020. Daniel Raimi, Neelesh Nerurkar, and Jason Bordoff, Columbia University CGEP.

Decommissioning Orphaned and Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells: New Estimates and Cost Drivers. 2021. Daniel Raimi, Alan J. Krupnick, Jhih-Shyang Shih, and Alexandra Thompson, ChemRXIV, Cambridge University Press.

August 1, 2021

By Blake Wright

Journal of Petroleum Technology

Magnetic surveys are used to guide ground-based field research more effectively. In addition to location data that is not always precise, wells are often difficult to identify in the field due to being buried or concealed by vegetation. Source: National Energy Technology Laboratory.

It’s a problem as old as the industry itself. The initial oil rush in the late 1800s spread like wildfire through Pennsylvania, and by 1891 the state’s annual crude output had hit 31 million barrels, or 58% of the nation’s total oil production for that year. However, by the turn of the century the bloom was off the rose. Pennsylvania’s once-robust oil allure had been eclipsed by finds in Texas, California, and Oklahoma, each spawning its own regional oil booms. So why the history lesson? Because it’s important to understand the potential volume and impact of orphan wells in the US.

In the infancy of the industry, plugging-and-abandonment (P&A) techniques were crude at best, if anyone even went to the trouble. Worse still was the overall record keeping at the time. With oil booms around the country setting off races to harness as much black gold as possible, wells were being drilled at breakneck pace. Once these earliest wells were tapped of their commercial usefulness, operators moved on to the next. There was little-to-no oversight. No regulations. No standards. The result? Thousands, if not more, of scattered, undocumented wells.

“Back in the day, you have people drilling wells, and nobody’s keeping track of where the wells are drilled and who owns the wells,” said Daniel Raimi, fellow with Resource for the Future, an independent institution that conducts environmental, energy, and natural resource research. “The government’s not keeping track and has little to no regulation in place to ensure that operators safely decommission their assets at the end of their lives. As a result, you have wells that maybe produce for a couple of years, and then the owners walk away. Multiply that by a couple of hundred thousand and now you’ve got a problem.”

Today, there is plenty of oversight and regulation for the industry to leave abandoned wells in much better shape than those earliest probes. However, orphan wells are still a problem. To paint the clearest picture, it would be prudent to define what an orphan well is.

This is where we run into our first problem. Definitions can vary wildly from state to state and organization to organization. Some lump all abandoned, unplugged wells into their counts as orphan wells. Others count all idle wells. However, for the sake of clarity we will define orphan wells as those nonproducing, idle wells whose ownership is unknown. By that definition it is safe to say that many of the nation’s earliest wells fit that criteria.

In more modern times, orphans result from idle wells whose owner goes belly-up prior to any P&A work. In most of these cases, bonds are employed to help offset the cost of plugging these wells. However, while they vary state to state, most bonding minimums do not cover the full cost of abandonment and remediation, if needed.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, there are about 2 million unplugged, abandoned oil and gas wells scattered across the US. Other experts place the number higher; some believe it is lower. Some researchers believe as many as half of those could be orphan wells. A survey by the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission in 2018 put the range of orphaned and idle wells at around 560,000 to 1.1 million. Again, abandoned doesn’t always mean orphaned. One fact that can be extrapolated from the data gathered to date is that no one knows for sure just how many orphaned wells are out there. But that is changing.

Documented and estimated undocumented orphaned oil and gas wells in the US. Source: Columbia University CGEP report.

The Hunt

Researchers like Natalie Pekney have dedicated about a decade’s worth of field work trying to locate, chronicle, and sample the potential hazards from the orphan wells across the US. Pekney is an environmental engineer with the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) who has conducted field work in Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania, her home state and in many ways ground zero for the orphan well issue. She and her team used aerial magnetic survey techniques to pinpoint potential orphan wells by identifying the metal well casings. A 2017 study of the Hillman State Park location, west of Pittsburgh in southwestern Pennsylvania, discovered more magnetic well readings than previously reported in the area’s well count database.

“We started doing this work at least 10 years ago,” said Pekney. “We had a team that was perfecting the approach of using aerial magnetic techniques for finding wells. They would fly the survey and then go out on the ground and check those locations to verify if there was or was not a well there. They were noticing sometimes at these wells they could see bubbling, or you could smell a strong hydrocarbon smell. So just anecdotally, one could assume that some of them were still leaking. Then we had a thought to go out and measure how much, so we’ve been doing the emissions measurements since 2015 or so.”

Over time, the lab released its magnetic well-location technology to the private sector, which now employs sensor-equipped drones for much of the survey work. Now the team focuses more on the methane-emissions work. The group was in the throes of conducting measurement studies in Kentucky when COVID-19 sidelined the effort.

“We’re just now making plans to go back there and try to complete that work,” said Pekney. “The same thing in New York. We had plans to go out there and we had to put those off because of the pandemic. We’re currently trying to start our fieldwork efforts back up now that a lot of the travel restrictions and such have been relaxed.”

Pekney said they really had no expectations of what they might find once they started tracking emissions. With no previously published data on the subject, they had nothing on which to base a guess. Ultimately, in the context of greenhouse gas emissions from all US oil and gas sources, estimated emissions from abandoned wells is but a fraction of the total. The Hillman State Park survey took samples from 31 wells (22 above ground, unplugged and nine buried). The average emissions rate for the aboveground wells was 0.70 kg of CH4 per well per day.

Methane emissions are also a hot topic in political circles. Methane has more the 80-times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere, making it public enemy number one in the fight against climate change and global warming.

“It’s not huge, but at the same time, it’s kind of a correctable problem in a sense because these wells, generally the high-emitting ones have not been plugged, and plugging is effective at eliminating or decreasing emissions,” said Pekney.

Over the course of the next few years, Pekney believes her group can assist states by helping with plugging prioritization—identifying the “super-emitters” and getting those dealt with first.

GPS-enabled computers assist researchers on the ground in finding and geolocating abandoned wells, such as the one pictured here. Source: NETL.

The Answer?

Both state and federal officials have been active in recent months regarding the plugging of orphan wells. Several bills are floating around at the federal level that would aim to put workers sidelined by the pandemic back to work plugging these wells.

Senator Michael Bennet’s (D-CO) The Oil and Gas Bonding Reform and Orphaned Well Remediation Act is aimed at cleaning up tens of thousands of orphaned wells across the nation and reforming the bonding system. The REGROW Act, sponsored by Senators Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) and Kevin Cramer (R-ND) would budget more than $4.6 billion to put skilled energy workers back to work cleaning up these sites, with the goal of plugging every documented orphan well in the country.

“Safety and environmental protection are top priorities for our industry, and we operate under strict standards and practices to ensure that American energy is produced responsibly from start to finish,” said Frank Macchiarola, American Petroleum Institute’s senior vice president of policy, economics, and regulatory affairs. “Our industry complies with all existing state and federal requirements for abandoned wells and reclaiming wells sites, and we will continue to support new efforts, like those outlined in the bipartisan REGROW Act, to plug these wells and further reduce methane emissions.”

Roughly $8 billion has been given out to states by the federal government for mine-reclamation projects over the past four decades. President Joe Biden’s recently announced $2.3-trillion infrastructure plan would earmark $16 billion toward the cleanup and plugging of old oil wells and mines, a significant step up in investment for orphan well remediation.

“Society is bearing a lot of the costs right now because of things like water pollution and methane emissions,” said Raimi. “That is costing all of us something. It’s just difficult to measure. There are some proposals at the federal level to inject dollars into state plugging programs. That’s a helpful first step, but it certainly doesn’t address the magnitude of the problem.

“From my perspective,” he continued, “the thing that would be most helpful is for us to have better information on which wells are most hazardous. Because with, let’s just say, a million orphaned wells, and 2.1 million unplugged abandoned wells, we must prioritize, and we can’t prioritize unless we know which wells pose the most risk to the environment and to public health.”

There is still a long road ahead for the solution to the orphan well problem, and with fresh bankruptcies during the past year due to the pandemic, the number of wells left to deal with continues to be a moving target. The energy transition could be both a sign for celebration and alarm. As assets exchange hands from bigger operators raising capital for greener projects to smaller, lower-cost producers, the new owners will look for every advantage to preserve the bottom line. That might include deferring abandonment work, because, frankly, there’s no money in that.

“At the very least, we’re in the tens of billions of dollars range,” said Raimi on the national tab for orphan well cleanup. “I don’t know what the ultimate number is going to be, and therefore we need more information. It’s possible that there are some orphaned wells out there that are not causing anybody any harm. They might be in the middle of prairie land, not leaking any methane, and not causing risk around water. Should we really spend $100,000 to plug a well like that? Probably not. But again, we don’t know which wells pose substantial risks and which don’t.”

Average plugging and restoration costs per well. Source: Columbia University CGEP report.

For Further Reading

Green Stimulus for Oil and Gas Workers: Considering a Major Federal Effort To Plug Orphaned and Abandoned Wells. 2020. Daniel Raimi, Neelesh Nerurkar, and Jason Bordoff, Columbia University CGEP.

Decommissioning Orphaned and Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells: New Estimates and Cost Drivers. 2021. Daniel Raimi, Alan J. Krupnick, Jhih-Shyang Shih, and Alexandra Thompson, ChemRXIV, Cambridge University Press.

Millions of Leaky and Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells Are Threatening Lives and the Climate

Biden’s Build Back Better agenda would cap them—while putting tens of thousands of people to work.

July 26, 2021 Jeff Turrentine

An abandoned oil drilling project in the Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania, where companies have abandoned thousands of wells in and around the area, walking away from cleanup responsibilities that could cost the state tens of millions of dollars.

Andrew Rush/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via AP

When a bipartisan group of senators was hammering out the details of a proposed national infrastructure package earlier this summer, compromise was inevitable.

But one aspect of the package required little to no compromise: the call to cap the millions of orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells that currently pockmark the country, from Alaska to New York to New Mexico. Whether it’s through the bipartisan infrastructure deal that’s currently being negotiated or through additional, upcoming recovery legislation, tackling this problem is essential—not only because these wells are dangerous polluters but also because doing so would create thousands of jobs in the process.

Taken together, these wells are a major source of air and groundwater pollution, as they continue to leak toxic substances such as arsenic and methane even after they’re no longer operational. But they also represent an all-too-rare point of political consensus: Just about everyone, from the reddest of red-state Republicans to the bluest of blue-state Democrats, agrees that the wells pose a serious threat to public health, that they need to be properly sealed, and that doing so will create jobs while making us all safer, whether from pollution or climate change or both.

Here’s what you need to know about these dangerous relics of fossil fuel extraction.

How many of them are there, and where are they located?

A recent investigation by Reuters estimates that the United States could have more than 3.2 million orphaned and abandoned wells. Some states have a few hundred; others have a few thousand. And some have a staggering number of them: Pennsylvania reportedly has more than 330,000 of these wells within its borders.

“Orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells are located everywhere,” says NRDC senior advocate Joshua Axelrod. “They can be in the middle of a forest, in backyards, in farm fields, even under sidewalks and houses.” Basically, they are anywhere that oil and gas development has taken place—at sites of large-scale operation spread out over many acres as well as single-well outfits on tiny parcels of land.

Why are they so dangerous?

Simple: Because they leak. Among the chemicals that can seep out and contaminate air, soil, or groundwater are hydrogen sulfide, benzene, and arsenic. Even the smallest leaks can adversely affect the local environment if they go unaddressed or undetected for many years.

Most alarmingly, though, these wells emit a lot of methane, an odorless gas that can seep into nearby buildings (a home, school, or office, for example) and pose major health hazards. When concentrated in enclosed spaces—such as a basement or a bedroom, for instance—methane will take the place of oxygen in the lungs and can cause weakness, nausea, vomiting, and convulsions. Long-term methane poisoning can even be fatal. And methane, of course, doesn’t just make people sick: It’s also highly explosive. In 2017, two men were killed while installing a hot water heater in the basement of a home in Firestone, Colorado, that had been built adjacent to an oil and gas field. When the neighboring petroleum corporation restarted a well that had been dormant for a year, a damaged flowline filled the basement with gas, which ignited into a fireball that destroyed the house in an instant.

Hanson Rowe, a landowner who blames a leaky gas well on his Salyersville, Kentucky, property for health problems

Bryan Woolston/Reuters

What’s the connection to climate change?

Though carbon dioxide emissions are easily the largest contributor to climate change in terms of volume, methane—the second-largest contributor—is actually 86 times more potent at trapping greenhouse gases over the first 20 years of its release into the atmosphere. In other words, small amounts of atmospheric methane can have the same heat-trapping power as much, much larger amounts of CO2.

According to the Reuters investigation, which conducted a comprehensive review of the available data in 2020, orphaned and abandoned wells in the United States were collectively responsible for emitting 281,000 tons of methane into the atmosphere in 2018. The report states that the collective methane release is “the climate-damage equivalent of consuming about 16 million barrels of crude oil,” which is nearly as much oil as the United States uses in a typical day. “Plugging orphaned and abandoned wells,” says Axelrod, “would lead to a measurable decrease in methane emissions and help us meet our climate goals.”

Why haven’t the fossil fuel companies that are responsible addressed this problem on their own?

It can cost anywhere between $10,000 and $50,000 to effectively seal off an older well, and as much as $300,000 to seal off a newer, deeper one. And while oil and gas companies are legally obligated to plug their wells, the economics of the industry—combined with lax regulation by states—means that few of these operators have the cash on hand or the incentive to adequately do their duty. It’s also not uncommon for oil companies to go bankrupt, leaving them with no means of cleaning up the physical ruin that they’ve created along the way to their own financial ruin.

In either case, the responsibility of remediation almost always ends up falling to the states, many of which are cash-strapped themselves. In May, the House Natural Resources Committee introduced a bill that would incentivize states to strengthen their own regulations by tying funding to these efforts. Still, at best, this would only solve the problem going forward, not address the cleanup of the backlog of three million wells.

Nathan Graber of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation hiking through the fog to find abandoned oil wells in Olean, New York

Lindsay DeDario/Reuters

How many U.S. jobs could a nationwide well remediation plan create?

“A lot,” says Axelrod. “The number depends on the size of the plan and the investment made. But a fairly middle-of-the-road estimate for the number of jobs that could be created if all orphaned and abandoned wells were to be located and plugged is on the order of 100,000 jobs per year for the next seven years.”

The infrastructure package proposed as part of President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda calls for $16 billion in funding to securely cap these wells (and also to close up abandoned mines, the coal industry’s version of this problem). Biden has made a point to stress that this nationwide program would create more union jobs with good wages. Many of the jobs would go to former oil and gas industry employees who have been laid off as a result of the pandemic and who would be arriving at their new work effectively pre-trained, with a basic understanding of the mechanics and technologies involved in the capping process. The president has also said that these workers would get paid “the same price that they would charge to dig those wells.”

Now that’s progress.

Tell Interior Sec. Haaland to help end destructive fossil fuel extraction

TAKE ACTION

NRDC.org stories are available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as time and place elements, style, and grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can't republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Biden’s Build Back Better agenda would cap them—while putting tens of thousands of people to work.

July 26, 2021 Jeff Turrentine

An abandoned oil drilling project in the Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania, where companies have abandoned thousands of wells in and around the area, walking away from cleanup responsibilities that could cost the state tens of millions of dollars.

Andrew Rush/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via AP

When a bipartisan group of senators was hammering out the details of a proposed national infrastructure package earlier this summer, compromise was inevitable.

But one aspect of the package required little to no compromise: the call to cap the millions of orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells that currently pockmark the country, from Alaska to New York to New Mexico. Whether it’s through the bipartisan infrastructure deal that’s currently being negotiated or through additional, upcoming recovery legislation, tackling this problem is essential—not only because these wells are dangerous polluters but also because doing so would create thousands of jobs in the process.

Taken together, these wells are a major source of air and groundwater pollution, as they continue to leak toxic substances such as arsenic and methane even after they’re no longer operational. But they also represent an all-too-rare point of political consensus: Just about everyone, from the reddest of red-state Republicans to the bluest of blue-state Democrats, agrees that the wells pose a serious threat to public health, that they need to be properly sealed, and that doing so will create jobs while making us all safer, whether from pollution or climate change or both.

Here’s what you need to know about these dangerous relics of fossil fuel extraction.

Tell Congress to heed climate warnings and pass the Build Back Better agenda

TAKE ACTION

TAKE ACTION

What are orphaned and abandoned wells?

Over the past hundred years, fossil fuel companies and some private landowners in the United States have drilled tens of millions of holes deep into the earth to extract oil and natural gas. When a well goes dry (as, ultimately, they all do), its operator moves on. “Orphaned” wells are those for which no former owner or operator can be located, while the term “abandoned well” typically refers to an unproductive well with a known owner/operator. In either case, the wells remain uncapped. They are essentially open holes in the ground that need to be cleaned and plugged with cement to stop their pollutants from escaping into the environment.

How many of them are there, and where are they located?

A recent investigation by Reuters estimates that the United States could have more than 3.2 million orphaned and abandoned wells. Some states have a few hundred; others have a few thousand. And some have a staggering number of them: Pennsylvania reportedly has more than 330,000 of these wells within its borders.

“Orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells are located everywhere,” says NRDC senior advocate Joshua Axelrod. “They can be in the middle of a forest, in backyards, in farm fields, even under sidewalks and houses.” Basically, they are anywhere that oil and gas development has taken place—at sites of large-scale operation spread out over many acres as well as single-well outfits on tiny parcels of land.

Why are they so dangerous?

Simple: Because they leak. Among the chemicals that can seep out and contaminate air, soil, or groundwater are hydrogen sulfide, benzene, and arsenic. Even the smallest leaks can adversely affect the local environment if they go unaddressed or undetected for many years.

Most alarmingly, though, these wells emit a lot of methane, an odorless gas that can seep into nearby buildings (a home, school, or office, for example) and pose major health hazards. When concentrated in enclosed spaces—such as a basement or a bedroom, for instance—methane will take the place of oxygen in the lungs and can cause weakness, nausea, vomiting, and convulsions. Long-term methane poisoning can even be fatal. And methane, of course, doesn’t just make people sick: It’s also highly explosive. In 2017, two men were killed while installing a hot water heater in the basement of a home in Firestone, Colorado, that had been built adjacent to an oil and gas field. When the neighboring petroleum corporation restarted a well that had been dormant for a year, a damaged flowline filled the basement with gas, which ignited into a fireball that destroyed the house in an instant.

Hanson Rowe, a landowner who blames a leaky gas well on his Salyersville, Kentucky, property for health problems

Bryan Woolston/Reuters

What’s the connection to climate change?

Though carbon dioxide emissions are easily the largest contributor to climate change in terms of volume, methane—the second-largest contributor—is actually 86 times more potent at trapping greenhouse gases over the first 20 years of its release into the atmosphere. In other words, small amounts of atmospheric methane can have the same heat-trapping power as much, much larger amounts of CO2.

According to the Reuters investigation, which conducted a comprehensive review of the available data in 2020, orphaned and abandoned wells in the United States were collectively responsible for emitting 281,000 tons of methane into the atmosphere in 2018. The report states that the collective methane release is “the climate-damage equivalent of consuming about 16 million barrels of crude oil,” which is nearly as much oil as the United States uses in a typical day. “Plugging orphaned and abandoned wells,” says Axelrod, “would lead to a measurable decrease in methane emissions and help us meet our climate goals.”

Why haven’t the fossil fuel companies that are responsible addressed this problem on their own?

It can cost anywhere between $10,000 and $50,000 to effectively seal off an older well, and as much as $300,000 to seal off a newer, deeper one. And while oil and gas companies are legally obligated to plug their wells, the economics of the industry—combined with lax regulation by states—means that few of these operators have the cash on hand or the incentive to adequately do their duty. It’s also not uncommon for oil companies to go bankrupt, leaving them with no means of cleaning up the physical ruin that they’ve created along the way to their own financial ruin.

In either case, the responsibility of remediation almost always ends up falling to the states, many of which are cash-strapped themselves. In May, the House Natural Resources Committee introduced a bill that would incentivize states to strengthen their own regulations by tying funding to these efforts. Still, at best, this would only solve the problem going forward, not address the cleanup of the backlog of three million wells.

Nathan Graber of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation hiking through the fog to find abandoned oil wells in Olean, New York

Lindsay DeDario/Reuters

How many U.S. jobs could a nationwide well remediation plan create?

“A lot,” says Axelrod. “The number depends on the size of the plan and the investment made. But a fairly middle-of-the-road estimate for the number of jobs that could be created if all orphaned and abandoned wells were to be located and plugged is on the order of 100,000 jobs per year for the next seven years.”

The infrastructure package proposed as part of President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda calls for $16 billion in funding to securely cap these wells (and also to close up abandoned mines, the coal industry’s version of this problem). Biden has made a point to stress that this nationwide program would create more union jobs with good wages. Many of the jobs would go to former oil and gas industry employees who have been laid off as a result of the pandemic and who would be arriving at their new work effectively pre-trained, with a basic understanding of the mechanics and technologies involved in the capping process. The president has also said that these workers would get paid “the same price that they would charge to dig those wells.”

Now that’s progress.

Tell Interior Sec. Haaland to help end destructive fossil fuel extraction

TAKE ACTION

NRDC.org stories are available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as time and place elements, style, and grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can't republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment