Reuters | December 20, 2022

Precious metals smelter at Glencore’s Kazzinc operations

Source: VisMedia

Where has all the zinc gone?

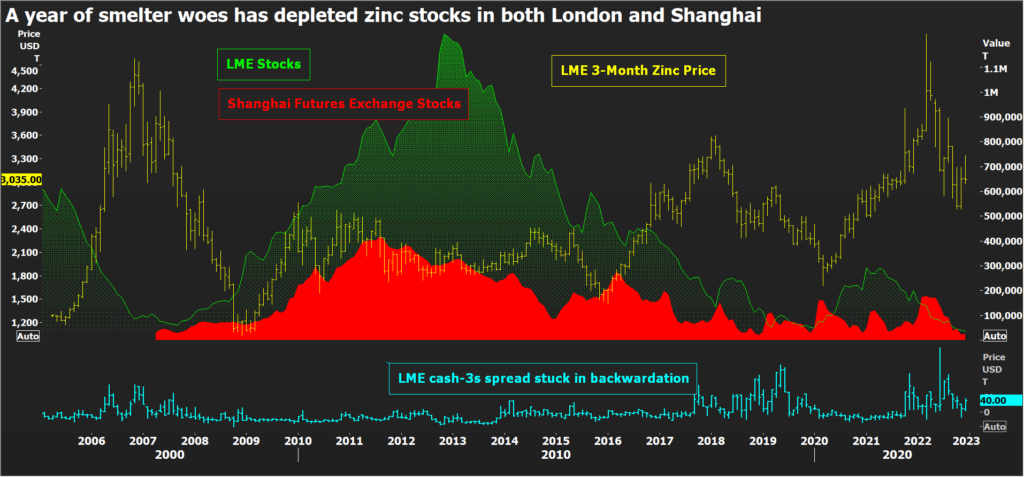

London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouse stocks of the galvanizing metal total 36,525 tonnes, the lowest amount this century.

Almost 60% of that metal is earmarked for physical load-out, leaving just 15,175 tonnes of live tonnage, no more than a few hours worth of global consumption.

Shanghai Futures Exchange stocks are equally depleted at 22,642 tonnes.

The clear-out of visible zinc inventory has played out in a year of weak demand, usage falling by 3.2% over the first 10 months of this year, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG).

But supply has fallen just as hard, reflecting an unprecedented year of smelter problems, particularly in Europe.

The LME zinc price has been under pressure this month, sliding from a high of $3,339 per tonne to a current $3,060 as the prospect of European recession further darkens the demand outlook.

But extremely low stocks and uncertainty over Europe’s smelter sector are cushioning the downside as the market continues to weigh up the relative under-performance of both supply and demand.

Where has all the zinc gone?

London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouse stocks of the galvanizing metal total 36,525 tonnes, the lowest amount this century.

Almost 60% of that metal is earmarked for physical load-out, leaving just 15,175 tonnes of live tonnage, no more than a few hours worth of global consumption.

Shanghai Futures Exchange stocks are equally depleted at 22,642 tonnes.

The clear-out of visible zinc inventory has played out in a year of weak demand, usage falling by 3.2% over the first 10 months of this year, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG).

But supply has fallen just as hard, reflecting an unprecedented year of smelter problems, particularly in Europe.

The LME zinc price has been under pressure this month, sliding from a high of $3,339 per tonne to a current $3,060 as the prospect of European recession further darkens the demand outlook.

But extremely low stocks and uncertainty over Europe’s smelter sector are cushioning the downside as the market continues to weigh up the relative under-performance of both supply and demand.

Smelter disruption

Global refined zinc output fell by 3.2% in January-October, according to the ILZSG, matching the drop-off in usage.

Production fell in China, Kazakhstan, Canada and Mexico, all of which are major sources of refined metal.

But the biggest hit was to European production this year as the region’s smelters faced an acute margin squeeze due to the rolling energy crisis.

Glencore mothballed its 100,000-tonne per year Portovesme plant in Italy at the end of 2021 and put its 165,000-tonne per year Nordenham smelter in Germany on care and maintenance last month.

Nyrstar, owned by Trafigura, did the same with its 315,000-tonne per year Dutch smelter in September, although the plant has since resumed production “on a limited basis”.

The company’s Auby smelter in France, by contrast, will now not come back from scheduled maintenance but remain on care and maintenance until further notice.

Other operators continue to adjust capacity in response to changes in local power pricing, which in Europe remains a fractured and highly variable landscape.

Global refined zinc output fell by 3.2% in January-October, according to the ILZSG, matching the drop-off in usage.

Production fell in China, Kazakhstan, Canada and Mexico, all of which are major sources of refined metal.

But the biggest hit was to European production this year as the region’s smelters faced an acute margin squeeze due to the rolling energy crisis.

Glencore mothballed its 100,000-tonne per year Portovesme plant in Italy at the end of 2021 and put its 165,000-tonne per year Nordenham smelter in Germany on care and maintenance last month.

Nyrstar, owned by Trafigura, did the same with its 315,000-tonne per year Dutch smelter in September, although the plant has since resumed production “on a limited basis”.

The company’s Auby smelter in France, by contrast, will now not come back from scheduled maintenance but remain on care and maintenance until further notice.

Other operators continue to adjust capacity in response to changes in local power pricing, which in Europe remains a fractured and highly variable landscape.

Changed trade flows

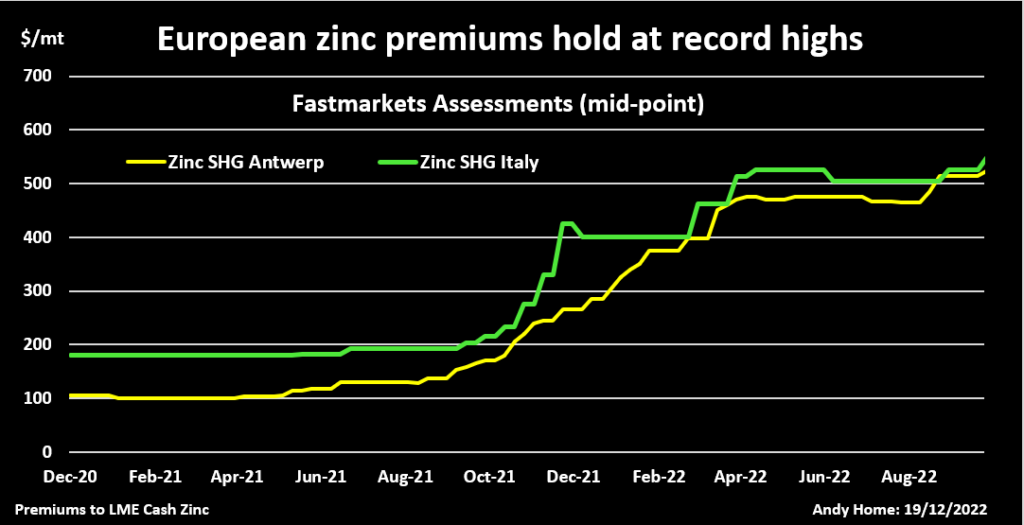

The loss of regional supply has kept European physical premiums elevated despite softening demand.

Fastmarkets assesses the northern European premium at a mid-point of $520 per tonne over LME cash and the southern at premium at $585 per tonne, a fresh record high.

The US physical market has been equally stretched, with availability not helped by the planned permanent closure of the Flin Flon smelter in Canada.

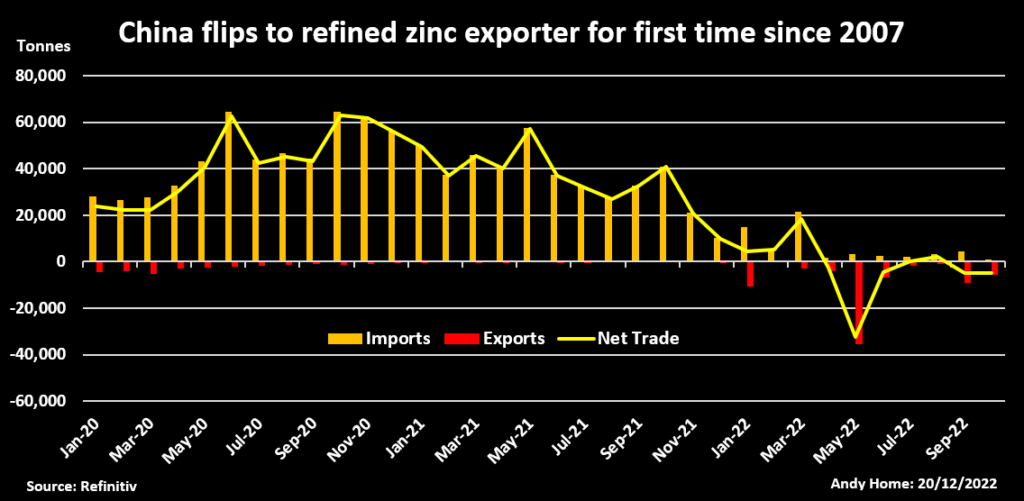

Such historically high premiums in the physical supply chain have both diverted metal from the terminal market and inverted China’s normal trade flows.

China has historically been a significant importer of refined zinc to the annual tune of 400,000-700,000 tonnes over the last decade.

This year it is on course to turn a net exporter for the first time since 2007. Imports collapsed and exports surged to 78,500 tonnes in the January-October period.

Almost half that tonnage has been shipped to Taiwan, noticeably one of the few LME delivery points to have seen any fresh inflows this year.

But Chinese zinc has also been exported to far-flung destinations such as Turkey, Italy, Mexico and the United States to plug gaps in the rest of the world’s supply.

The outbound flow of metal has acted to drain Chinese stocks, both visible and those lying in the off-market shadows. Shanghai Metal Market (SMM) estimates total “social” inventories of zinc ingot across seven domestic markets at a low 56,000 tonnes.

The loss of regional supply has kept European physical premiums elevated despite softening demand.

Fastmarkets assesses the northern European premium at a mid-point of $520 per tonne over LME cash and the southern at premium at $585 per tonne, a fresh record high.

The US physical market has been equally stretched, with availability not helped by the planned permanent closure of the Flin Flon smelter in Canada.

Such historically high premiums in the physical supply chain have both diverted metal from the terminal market and inverted China’s normal trade flows.

China has historically been a significant importer of refined zinc to the annual tune of 400,000-700,000 tonnes over the last decade.

This year it is on course to turn a net exporter for the first time since 2007. Imports collapsed and exports surged to 78,500 tonnes in the January-October period.

Almost half that tonnage has been shipped to Taiwan, noticeably one of the few LME delivery points to have seen any fresh inflows this year.

But Chinese zinc has also been exported to far-flung destinations such as Turkey, Italy, Mexico and the United States to plug gaps in the rest of the world’s supply.

The outbound flow of metal has acted to drain Chinese stocks, both visible and those lying in the off-market shadows. Shanghai Metal Market (SMM) estimates total “social” inventories of zinc ingot across seven domestic markets at a low 56,000 tonnes.

Recovery rates

Zinc pricing this year has reflected the conundrum of weak Chinese demand, thanks largely to a struggling property sector, and simultaneous supply-chain tightness in the rest of the world.

Next year’s outlook depends a lot on whether demand or supply recovers fastest, assuming either recovers at all.

Recession in Europe will come before recovery in China, according to analysts at Citi. The bank’s base-case forecast is for the zinc price to ease steadily to $2,600 per tonne in the third quarter of 2023 to reflect the Western demand hit.

Macquarie Bank agrees, forecasting prices to bottom out at $2,500 in the second quarter and to remain subdued as the market shifts back to surplus.

A return to surplus, however, assumes that the supply side can recover from this year’s collective under-performance.

China’s lifting of restrictions and rising demand should incentivize the country’s smelters to turn back on the taps after what SMM estimates to have been a 2.0% slide in national output so far this year.

High treatment charges, currently around $270-290 per tonne in China, will help smelter margins both there and everywhere else.

That should in theory pave the wave for European smelters to reactivate capacity once the power crisis abates, most likely in the second quarter as the region emerges from winter.

But smelters of any metal have a history of staying closed after a prolonged period of inactivity, the costs of reopening sometimes not worth the return.

Moreover, while European power prices have fallen significantly in recent weeks, they remain well above levels that were regarded as normal before Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine.

The longer-term question-mark over Europe’s power-hungry smelters hasn’t gone away, injecting a whole new twist in the zinc market narrative.

In the short term the zinc market is going to remain beholden to the European power market. Any more smelter suspensions or any shift to permanent closures could yet turn a bearish market on its head.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by David Evans)

Zinc pricing this year has reflected the conundrum of weak Chinese demand, thanks largely to a struggling property sector, and simultaneous supply-chain tightness in the rest of the world.

Next year’s outlook depends a lot on whether demand or supply recovers fastest, assuming either recovers at all.

Recession in Europe will come before recovery in China, according to analysts at Citi. The bank’s base-case forecast is for the zinc price to ease steadily to $2,600 per tonne in the third quarter of 2023 to reflect the Western demand hit.

Macquarie Bank agrees, forecasting prices to bottom out at $2,500 in the second quarter and to remain subdued as the market shifts back to surplus.

A return to surplus, however, assumes that the supply side can recover from this year’s collective under-performance.

China’s lifting of restrictions and rising demand should incentivize the country’s smelters to turn back on the taps after what SMM estimates to have been a 2.0% slide in national output so far this year.

High treatment charges, currently around $270-290 per tonne in China, will help smelter margins both there and everywhere else.

That should in theory pave the wave for European smelters to reactivate capacity once the power crisis abates, most likely in the second quarter as the region emerges from winter.

But smelters of any metal have a history of staying closed after a prolonged period of inactivity, the costs of reopening sometimes not worth the return.

Moreover, while European power prices have fallen significantly in recent weeks, they remain well above levels that were regarded as normal before Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine.

The longer-term question-mark over Europe’s power-hungry smelters hasn’t gone away, injecting a whole new twist in the zinc market narrative.

In the short term the zinc market is going to remain beholden to the European power market. Any more smelter suspensions or any shift to permanent closures could yet turn a bearish market on its head.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by David Evans)

No comments:

Post a Comment