America Will Have a Working Fusion Reactor Within 12 Years, Come Hell or High Water

Darren Orf

Fri, September 29, 2023

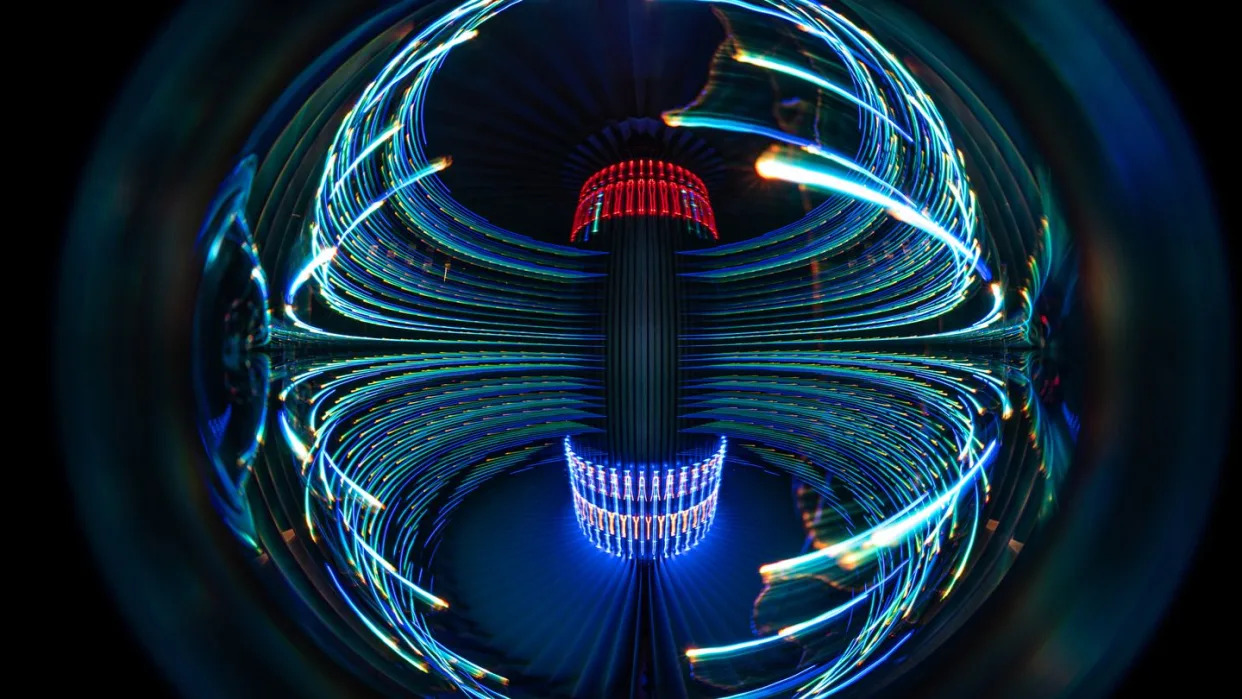

Alexandr Gnezdilov Light Painting - Getty Images

Jennifer Granholm, secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy, announced on Monday that the U.S. is aiming to create a working fusion reactor by 2035.

The U.S. currently funds various projects engaged in trying to realize the clean energy dream of nuclear energy.

Though fuel was added to the fire by the U.S. achieving fusion ignition in December of 2022, realizing the promise of nuclear fusion still faces many engineering and technological obstacles.

Nuclear fusion—the explosive physics that powers the hearts of countless stars, including our own—is the ultimate energy source. For decades, scientists have touted the many benefits of nuclear fusion. It’s more efficient, doesn’t produce waste, and can’t be used for weapons of mass destruction (without a fission counterpart). By all accounts, it’s an important energy solution that could seriously help curtail humanity’s addiction to fossil fuels. And the Biden Administration agrees.

According to the Associated Press (AP), U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm announced on Monday that creating a working commercial fusion reactor within the president’s “decadal vision of commercial fusion” was “not out of the realm of possibility.” In other words, to goal is to have a working reactor in the next (approximately) 10 years.

The U.S. is currently funding several pilot programs from various companies hoping to achieve the dream of commercial fusion through a variety of different means, whether it be lasers, magnets, or any one of the plethora of designs in between.

“It doesn’t guarantee a particular company will get there, but we have multiple shots on goal,” Dennis Whyte, director of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center, told the AP. “It’s the right way to do it, to support what we all want to see: commercial fusion to power our society.”

For decades, nuclear fusion was the “flying car” of the physics world—always perpetually 20 years down the road. But in the past few years, things have changed. Some of the U.S.’s leading energy companies and laboratories have contributed to the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) tokamak project in southern France, which hopes to achieve first plasma by November of 2025.

But the biggest news arrived in December 2022 when Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), an inertial fusion facility whose primary mission is to test the reliability of the U.S.’s nuclear weapons, achieved ignition by using 192 lasers to collapse a pellet of deuterium and tritium for 100 trillionths of a second. Within that brief window, the reaction bootstrapped itself, and there was a net energy gain. Eight months later, LLNL announced that they’d achieved a second ignition with increased net energy gains.

Because of these breakthroughs, fusion science is now a question of engineering and technology rather than pure, base-level understanding. For example, scientists still need to discover or create materials that can withstand the intense heat—some 10 times hotter than our sun—that fusion reactors require for long stretches at a time. They also need to perfect the beryllium-lined blankets in tokamaks, the devices responsible for converting a neutron’s kinetic energy into heat energy.

If the U.S. can stick the landing on its fusion energy promise, it’ll come nearly a century after the discovery of fusion as the life-sustaining energy source behind our Sun. The realization of the long-promised dream of nearly limitless clean energy may be closer than we thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment