Trudeau eyes boost to housing in new budget as firms worry about tax hikes

, Bloomberg News

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s upcoming budget is likely to put significant money toward boosting Canada’s housing supply, according to people familiar with the plans, adding pressure on the government to find more revenue.

Freeland and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau have been trying for months to quell rising public frustration over the high cost of homes, announcing plans to give billions to cities in return for changes that accelerate construction, among other moves. The government is working on other housing-affordability policies in advance of Freeland’s April 16 budget, the people said, speaking on condition they not be identified.

The government may also have to commit more money for industrial subsidies, defense, university research and drug plans in that document. New measures to raise revenue are likely if Freeland is to stick to her promise to keep deficits from growing — unless she cuts spending in other areas. That has some in Canada’s business community concerned the government will introduce corporate tax increases to fill the gap.

In November, the government projected annual deficits about $40 billion (US$29.6 billion) between 2023 and 2026 — but the country’s fiscal watchdog has already raised doubts it will meet this year’s target.

Home construction activity was soft in parts of Canada last year as higher interest rates and slow approval times discouraged many developers from starting projects. Meanwhile, surging rents have led to new debate about whether the country can continue to absorb large numbers of immigrants.

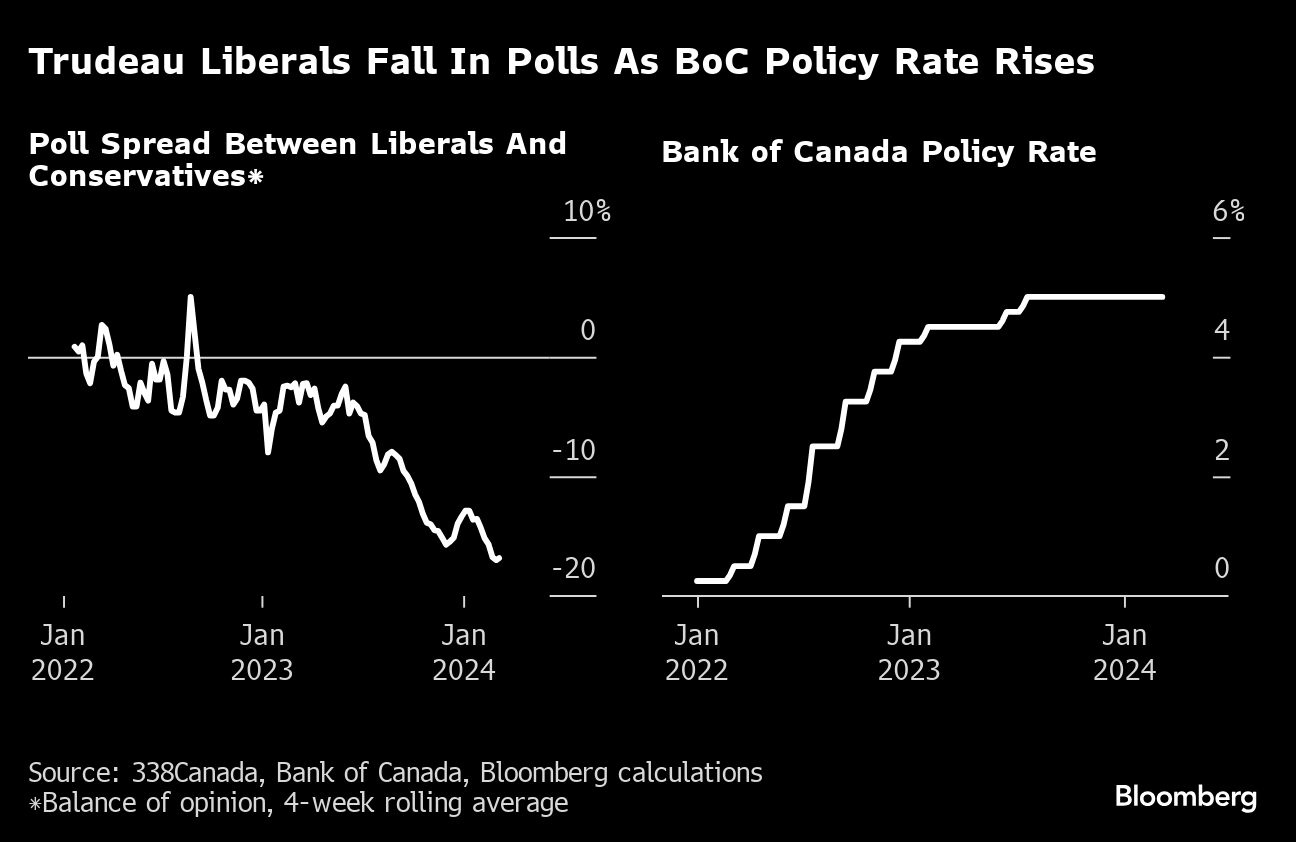

Trudeau and Freeland face political constraints, in addition to financial ones, as they craft what will be one of their final budgets before the next election. They can’t afford to produce a fiscal plan that’s seen as inflationary. The governing Liberal Party is far behind Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives in opinion polls, and officials are eager to see the Bank of Canada cut interest rates.

Some business leaders are worried Freeland is considering hiking corporate taxes, such as a broad-based tax on profits of large companies. It’s a tactic the government has used before: in 2022, Freeland levied a one-time tax on windfall profits by major banks and insurers, and last fall Trudeau threatened grocers with new taxes if they didn’t help rein in food inflation.

An excess profits tax would be favored by the opposition New Democratic Party, which is propping up Trudeau’s government in Parliament.

“The latest rumor in Ottawa is the government will try to solve its problem by introducing a new corporate tax — one that targets Canada’s most successful companies,” Goldy Hyder, chief executive officer of the Business Council of Canada, wrote in an editorial published in The Hub on Wednesday.

Hyder said large businesses “have become a popular punching bag for politicians,” but warned that taxing profits would “further discourage business investment in Canada and force successful Canadian companies to either constrain or cancel any growth plans.”

Freeland’s office declined to comment on any potential tax measures in the budget.

Still, Trudeau and Freeland may decide a battle with business over taxes is preferable to letting the deficit run higher, or failing to address concerns about housing. A loose fiscal policy risks giving pause to the central bank’s rate-setting committee as it debates whether and when to start lowering borrowing costs.

Some economists point out that government spending in recent years — including on Covid-19 emergency programs, which led to a record $328 billion federal deficit in the first year of the pandemic — has already complicated the central bank’s job. Last year, Bank of Nova Scotia economists estimated that the combined spending of provincial and federal governments forced the Bank of Canada to add as much as 200 basis points of tightening.

On the other hand, drastically cutting spending now risks weakening an economy that’s already struggling.

“Now that rates have gone up this much, I don’t think it would be especially constructive to really slam the brakes on the fiscal side,” said Doug Porter, chief economist with Bank of Montreal, adding that he’d still “heavily caution against spending a lot more at this stage.”

The government will get some help from a spending review recently led by Treasury Board President Anita Anand, which she says “refocused” $10.5 billion in planned travel and consulting expenses over the next three years toward priorities such as housing, health care and the clean economy.

Still, the spending estimates she introduced in Parliament project $449.2 billion in spending in the upcoming fiscal year — on top of anything to be announced in the spring budget. That’s an increase of $16.3 billion, or 3.8 per cent, from the main estimates for the current fiscal year, which ends March 31.

Anand rejected calls to cut spending. “We did not want to undermine services to Canadians,” she said in an interview. “We’re reallocating money that can be used for a higher purpose.”

Trudeau has taken some steps to reduce inflationary pressures. After a record surge in international students, Immigration Minister Marc Miller set a cap on the number of study permits. That’s expected to ease pressure on rental costs, which rose 6.5 per cent last year.

There’s also some inflation risk attached to the budget plans of provincial governments, which are planning to ramp up spending. British Columbia recently projected its budget deficit will widen by a third to a record $7.91 billion in the coming fiscal year. “I think there are some question marks about how much fiscal restraint or stimulus there will be at the provincial level,” said Avery Shenfeld, chief economist at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.

No comments:

Post a Comment