Openly promoting decolonization and a social democratic alternative, a historic coalition made record electoral gains.

By Jonathan Ng ,

December 10, 2024

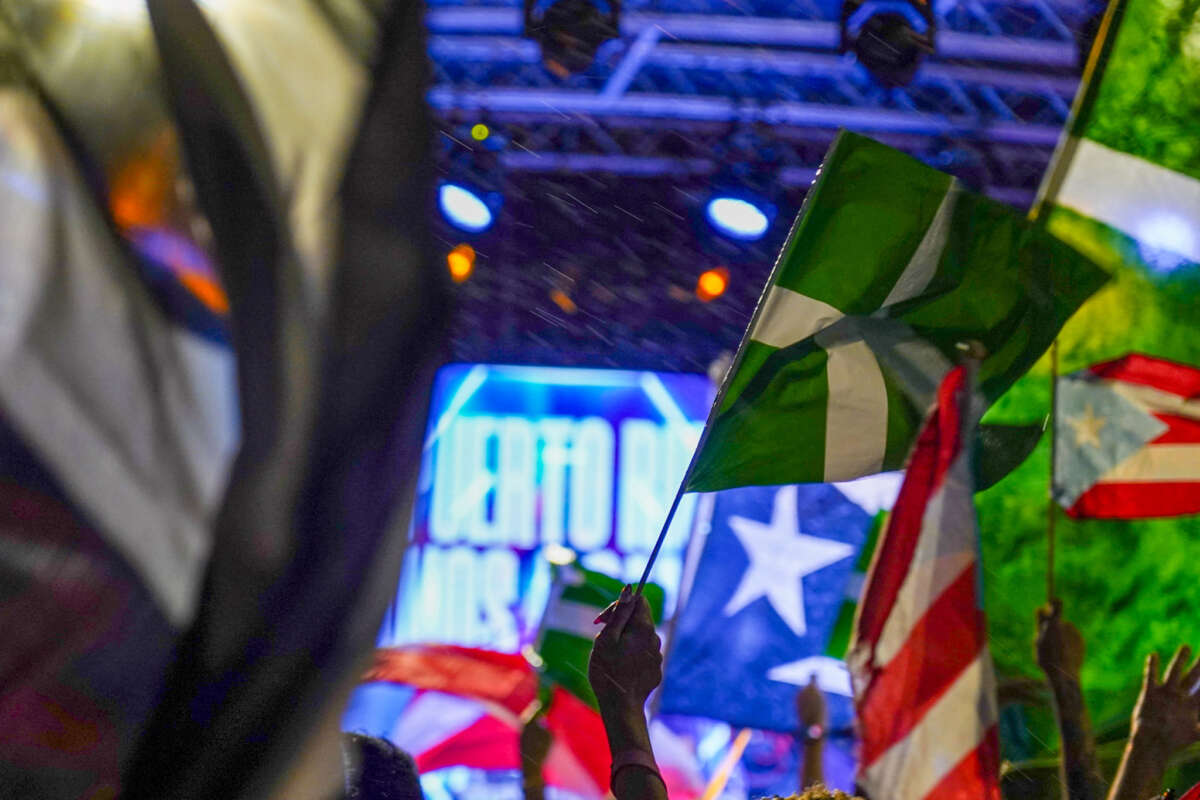

People wave flags of the Puerto Rican Independence Party as they react to the election results, in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on November 5, 2024.J

aydee Lee Serrano / AFP via Getty

Weeks after the November elections, officials in Puerto Rico are still counting votes. The agonizing delays and inefficiency have elicited frustration and calls for serious electoral reform.

Yet one outcome appears undeniable: The pro-independence candidate for governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Dalmau, made record electoral gains. According to a preliminary review, Dalmau received the second-most votes while representing the Alliance, a historic coalition between the Puerto Rican Independence Party and Citizens’ Victory Movement.

Months before the election, the Alliance’s meteoric rise shocked pollsters, putting Dalmau in a tight race with Jenniffer González of the reigning New Progressive Party. For decades, González and her party have favored big business and austerity policies that exacerbate inequality. Under pressure from Dalmau, she relied on heavy corporate contributions and a smear campaign portraying him as a communist to claim victory.

Stay in the loop

Never miss the news and analysis you care about.

Email*

Founded in 2023, the Alliance promotes social programming, public investment, gender equity and environmental protections. Its growing appeal signifies the potential realignment of Puerto Rico’s two-party system, embarrassing the once dominant Popular Democratic Party and putting conservatives on edge.

But more than anything, Dalmau’s electoral gains reflect an escalating legitimacy crisis for the colonial order. Puerto Rico is the oldest colony in the world, and the United States’s rule has grossly exacerbated political corruption, a major debt crisis and widespread poverty. In recent years, the left-leaning parties and social movements that comprise the Alliance have openly promoted “decolonization” and a social democratic alternative. Their mobilization challenges 126 years of colonial violence and exploitation — and bears the scars of past confrontations against a repressive status quo.

Related Story

Op-Ed |

Politics & Elections

As VP Harris Visits Puerto Rico, Puerto Ricans Call for End to US Colonialism

Vice President Kamala Harris is visiting Puerto Rico during a week marking the abolition of slavery and a massacre.

By Erica González Martínez , TruthoutMarch 21, 2024

State of Exception

In July 1898, U.S. forces seized Puerto Rico from Spain, in order to gain a strategic launchpad for operations across the Caribbean and assert control over the Panama Canal. Only two weeks after the invasion, a “commercial army” of businessmen arrived by steamship seeking commercial opportunities. In a stampede of speculation, foreign investors bought up land before the U.S. had even signed a peace agreement with Spain.

Over the following decades, foreign capitalists transformed Puerto Rico’s economy, consolidating its lush farmland into massive sugar plantations. By 1929, four U.S. corporations controlled almost 70 percent of sugarcane fields, brazenly buying the votes of workers, bribing local legislators and violating a law that prohibited the formation of estates over 500 acres.

A 1924 article in National Geographic boasted that “no other nation in history has ever created a finer record in colonial administration” than the U.S. in Puerto Rico. In reality, the majority of the population lived in poverty, as corporations drove peasants off their land and turned them into ruthlessly exploited day laborers. Although leading the colonial government, Luis Muñoz Rivera of the Unionist Party was privately scathing. “Blame will fall on the landowners who abuse their workers,” he confided to a colleague. “Capital wants everything and takes it from labor. We are their accomplices because of our inexcusable silence.”

Colonial officials not only exploited the wealth but also the health of Puerto Rico, turning the island into a captive laboratory for medical research. Most notoriously, The Rockefeller Foundation hired Cornelius Rhoads, who called his Puerto Rican patients “experimental ‘animals’” while studying malnutrition.

In 1932, pro-independence supporters ignited a scandal by publishing one of his private letters. “Porto Ricans,” Rhoads wrote, “are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. What this island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population.” Rhoads claimed that he had already contributed to “the process of extermination by killing off 8.”

Despite public backlash, he escaped with his reputation intact, later receiving a flattering feature in Time magazine for his medical research.

Echoing Rhoads, most U.S. officials claimed that “overpopulation,” rather than exploitation, was the main cause of Puerto Rico’s poverty. Adopting an aggressive birth control program, they tested contraceptives on residents and eventually sterilized one-third of the female population of reproductive age. Feminists later argued that the policy constituted a form of “genocide,” since doctors forced women in labor to accept sterilizations and apparently targeted minors to meet “quotas.”

The coercive medical experiments, sprawling sugar plantations and pervasive racism of officials reflected the colonial status of Puerto Rico. For U.S. authorities, the archipelago was an “unincorporated territory” that “belong[ed] to” the U.S., but was “not a part of” it. As sociologist José Atiles-Osoria argues, Puerto Rico became a nation suspended in a permanent state of exception: a territory without sovereignty that foreign soldiers, investors and scientists exploited at will.

Outlawing the Nation

During the 1930s, a burgeoning independence movement emerged under the leadership of Pedro Albizu Campos and the Nationalist Party, which propounded Spanish-language education, workers’ rights and a clean break from the United States. A spellbinding speaker, Albizu Campos promoted international solidarity with anti-colonial forces, while backing a mass strike that immobilized the sugar industry in 1934. The previous year, the unemployment rate had hit 65 percent, dramatizing the failures of U.S. rule.

Fearing the movement’s appeal, authorities militarized the police, arming members with submachine guns, rifles and riot gear. In 1935, security forces massacred a group of independence supporters in Río Piedras returning from a political rally. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and local officials harassed and spied on independence activists in dozens of cities, imprisoning Albizu Campos and opening thousands of illegal “carpetas” (“files”) on citizens. Opposed to dissent, Gov. Blanton Winship left little room for ambiguity: “In front of the nationalists, always shoot to kill.”

Tensions peaked in March 1937, as the Nationalist Party planned a parade in Ponce commemorating the abolition of slavery. Preparing to smash the procession, Capt. Felipe Blanco ordered subordinates to bring reinforcements that “shoot well,” while Governor Winship monitored developments from a nearby farm.

As the march began, around 200 police suddenly opened fire, mowing down civilians with automatic weapons. The newspaper El País reported that streets ran with blood, giving the city “the unpleasant appearance” of “a butcher shop.” Police finished off the injured with pistol shots and billy club blows, while riddling both adult and child spectators with bullets. Ultimately, they killed 19 people and wounded about 200 others.

The Ponce massacre had an immediate chilling effect, prompting a mass exodus from the Nationalist Party, intimidating independence advocates and offering a pretext for another wave of repression. Over the following decade, Winship and his successors exploited “every mechanism at their disposal to combat, isolate, or eliminate the independence movement,” according to the Puerto Rico Civil Rights Commission.

Above all, the imprisonment of Albizu Campos reflected the ferocity of colonial policy. Despite claiming he was mentally ill, the FBI plotted to drop “a psychological bombshell” inducing “stress and strain” on him, and captors allegedly tortured the independence leader with radiation, turning his skin into a tapestry of spreading burn marks.

Ultimately, the campaign of intimidation weakened the Nationalists, and convinced other parties to withdraw support for independence altogether. Through raw violence and subtle pressure, U.S. policy makers squeezed the parameters of acceptable political debate, stigmatized dissent and convinced the local elite to respect the implicit limits of Puerto Rico’s colonial order.

The Model Police State

By the late 1940s, pressure from the United Nations and decolonizing Global South compelled the U.S. to address the most glaring features of the colonial regime. In 1950, President Harry Truman and Gov. Luis Muñoz Marín announced that Puerto Rico would become a “Free Associated State” (FAS), fostering the illusion of self-determination even as the federal government retained control over its security, trade, foreign policy, and other essential domains.

By revising the territory’s status, Washington modernized the colonial order to preserve it, allowing Puerto Ricans to elect local officials, maintain a nonvoting representative in the U.S. Congress and enjoy limited “autonomy” — giving colonialism a Puerto Rican face and democratic façade.

Gov. Muñoz Marín became the preferred collaborator of the U.S., while lobbying for the FAS and stifling political dissent. He and the FBI developed a tense yet symbiotic relationship. The historian Nelson Denis claims that the agency leveraged knowledge of his opium addiction to keep Muñoz Marín on a tight leash. Meanwhile, he manipulated its obsession with communism to muzzle his political opponents. Privately, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover mused that “Gov. Muñoz Marín wants his own banana republic, with American air conditioning.”

To discredit the FAS project, the badly battered Nationalist Party launched an uprising in October 1950. Through a dramatic confrontation, organizers hoped to expose the colonial architecture of the political system and gain international support for independence. They seized at least 10 towns and even tried to assassinate President Truman in Washington, D.C.

Authorities responded with indiscriminate fury. Soldiers leveled the towns of Jayuya and Utuado with air raids, before executing revolutionaries without a trial. Attorney General Vicente Géigel Polanco recalled that Muñoz Marín “ordered that all the nationalists in Puerto Rico were arrested.” Police ripped civilians from bed at machine-gun point, imprisoning nearly 1,000 in only two days. The list of “subversives” that they used was so broad that it included Muñoz Marín’s own wife and a future chief justice of Puerto Rico’s Supreme Court — the result of two decades of unrelenting surveillance.

Throughout the Cold War, the violent policies that drowned out the October uprising persisted, even as National Geographic and other U.S. media claimed that Puerto Rico was “a model for Latin America” and “a booming showcase of democracy.”

Repression noticeably heightened after the Cuban Revolution inspired a new generation of political activists. During the 1970s, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, Young Lords Organization, Macheteros, and other New Left groups not only promoted independence but a socialist alternative. Once more, U.S. authorities responded with a heavy hand: screening job candidates across the island, opening the mail of dissidents, and targeting critics with surveillance operations, smear campaigns and even death squads. In July 1978, police notoriously lured student activists to Cerro Maravilla before murdering them in cold blood.

The ethical compromises, political manipulation and structural violence that Muñoz Marín and the Free Associated State enshrined left a corrosive legacy. As the Cold War ended, Supreme Court Justice Antonio Negrón García admitted that law enforcement practices were “typical of a fascist terror or military dictatorships.” In the end, police compiled 16,793 dossiers and 151,541 reference cards on alleged dissidents, overwhelming the Intelligence Division’s offices and compelling officers to store files in their own homes. Puerto Rico remained in geopolitical purgatory: a colony that had missed the great drama of the 20th century, decolonization, yet could not escape the past.

Island Warlords

Since the Cold War ended, U.S. colonialism has remained a violent and inescapable reality for residents of Puerto Rico. A 2022 American Medical Association article concludes that “Colonialism is literally killing Puerto Ricans,” as the restructuring of the territory’s finances has gutted the health care system and public services. A rolling debt crisis, decades of austerity and a heavily militarized law enforcement system continue to infuse everyday life with shades of repression.

Nowhere is this clearer than Vieques, an island that the Navy historically commandeered for military exercises by bulldozing entire neighborhoods to the ground. By the late 1990s, the military occupied 75 percent of the island, while sowing its beaches with explosives. In a cruel twist, the U.S. effectively waged war against Vieques while claiming to defend it — literally bombing hills into dust. Later, government investigators concluded that shooting exercises were turning the island “into a desert,” even leading to the “disfiguration of mountains.”

Beyond “strangling” the local economy, investigators stressed, the military fostered “a culture of violence.” Rape was commonplace. Lucía Meléndez Sanes recalled that soldiers arrived in her neighborhood “looking for girls” in the evening. “You could not be outside at that hour because they behaved like animals in the street.” Parents hid their daughters, while living in constant fear. As U.S. forces occupied Afghanistan, Vieques resident Carmen Valencia emphasized that “we knew what terrorism was because of them. Because we lived in terror all the time.”

In 1999, fighter pilots accidentally bombed a local security guard, David Sanes Rodríguez, galvanizing a national movement to expel the military. Over four years, authorities arrested over 1,000 people for civil disobedience, as residents camped on shooting ranges and beaches. A government commission discovered that the military had fired depleted uranium shells, poisoned water with explosives and almost bombed the local capital, Isabel Segunda. Investigators also reported that Navy exercises routinely unleashed seismic waves that “shake educational facilities, affecting the educational process.”

Movement pressure forced the base to close in 2003, but Vieques remains a war zone. Residents still struggle to regain access to their land, while demanding the military remove decades of debris and unexploded ordnance. So far, the Pentagon has collected over 41,000 projectiles and 32,000 bombs, estimating that the monumental cleanup initiative will last until 2032.

Death by Colonialism

In many ways, U.S. policy in Vieques dramatizes broader patterns of colonial violence in Puerto Rico, as federal authorities, foreign capital and a corrupt local elite impose punitive austerity measures that destroy the economy and public sector, making the explosive power of bombs unnecessary.

For decades, the territory has struggled with unsustainable debt, and officials have responded by slashing funds for health care and education while privatizing control of the electrical grid. Puerto Rico’s colonial status vastly complicates the crisis, since the territory lacks the power to declare bankruptcy or renegotiate its financial obligations. In 2016, the Supreme Court reaffirmed in Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle that Congress possesses ultimate sovereignty over the archipelago. That same year, the federal government appointed an oversight board staffed by foreign financiers to manage its budget, rudely dispelling the illusion of Puerto Rican “autonomy.”

The results have been disastrous. Within only two years, authorities closed 438 schools, while cuts to health services have spiked rates of cardiovascular disease, mental illness and other ailments. Between 2010 and 2020, Puerto Rico lost over 10 percent of its population, as economic turmoil compels residents to emigrate — a trend that accelerated after Hurricane María devastated the archipelago in 2017.

Repeatedly, law enforcement agencies have met anti-austerity protests with brute force, recycling tactics developed to repress the independence movement. The ACLU asserts that the Puerto Rico Police Bureau is “plagued by a culture of violence” and “has run amok for years,” while the Department of Justice admits that “constitutional violations” are “pervasive and plague all levels.”

In this light, the 2024 gubernatorial election is a major milestone signifying the repudiation of the colonial order and its pervasive violence.

Until recent months, the projected winner was Jenniffer González, who has long defended austerity and police brutality against protesters, alleging that student demonstrators plot to “destroy democracy through violence.” A week before the election, a comedian at a Trump campaign claimed that Puerto Rico was “a floating island of garbage,” embarrassing González, who fervently supports the Republican leader.

By contrast, Juan Dalmau of the Puerto Rican Independence Party represents a movement that U.S. authorities have persecuted since the Ponce massacre. A lawyer, Dalmau began his career investigating the infamous police “carpetas,” before himself being arrested for protesting the military occupation of Vieques. Indeed, the historical connections run deep: At his closing campaign rally, a star-studded lineup of artists paid homage to Albizu Campos and the Nationalist Party.

Dalmau’s electoral clout shocked observers, raising serious talk of a pro-independence governor for the first time. Although he lost, the election constitutes only one chapter in an ongoing history of resistance. The Alliance and community activists continue to combat private mismanagement of the electrical grid, foreign investors and political violence — recently advocating for the formation of a Department of Human Rights.

The colonial order is exhausted yet unyielding. Suspended in political purgatory, Puerto Rico remains in but not of the U.S. — its residents creatively resisting the violence of an empire that excludes them.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

.

Jonathan Ng is a postdoctoral fellow at the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College.

Yet one outcome appears undeniable: The pro-independence candidate for governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Dalmau, made record electoral gains. According to a preliminary review, Dalmau received the second-most votes while representing the Alliance, a historic coalition between the Puerto Rican Independence Party and Citizens’ Victory Movement.

Months before the election, the Alliance’s meteoric rise shocked pollsters, putting Dalmau in a tight race with Jenniffer González of the reigning New Progressive Party. For decades, González and her party have favored big business and austerity policies that exacerbate inequality. Under pressure from Dalmau, she relied on heavy corporate contributions and a smear campaign portraying him as a communist to claim victory.

Stay in the loop

Never miss the news and analysis you care about.

Email*

Founded in 2023, the Alliance promotes social programming, public investment, gender equity and environmental protections. Its growing appeal signifies the potential realignment of Puerto Rico’s two-party system, embarrassing the once dominant Popular Democratic Party and putting conservatives on edge.

But more than anything, Dalmau’s electoral gains reflect an escalating legitimacy crisis for the colonial order. Puerto Rico is the oldest colony in the world, and the United States’s rule has grossly exacerbated political corruption, a major debt crisis and widespread poverty. In recent years, the left-leaning parties and social movements that comprise the Alliance have openly promoted “decolonization” and a social democratic alternative. Their mobilization challenges 126 years of colonial violence and exploitation — and bears the scars of past confrontations against a repressive status quo.

Related Story

Op-Ed |

Politics & Elections

As VP Harris Visits Puerto Rico, Puerto Ricans Call for End to US Colonialism

Vice President Kamala Harris is visiting Puerto Rico during a week marking the abolition of slavery and a massacre.

By Erica González Martínez , TruthoutMarch 21, 2024

State of Exception

In July 1898, U.S. forces seized Puerto Rico from Spain, in order to gain a strategic launchpad for operations across the Caribbean and assert control over the Panama Canal. Only two weeks after the invasion, a “commercial army” of businessmen arrived by steamship seeking commercial opportunities. In a stampede of speculation, foreign investors bought up land before the U.S. had even signed a peace agreement with Spain.

Over the following decades, foreign capitalists transformed Puerto Rico’s economy, consolidating its lush farmland into massive sugar plantations. By 1929, four U.S. corporations controlled almost 70 percent of sugarcane fields, brazenly buying the votes of workers, bribing local legislators and violating a law that prohibited the formation of estates over 500 acres.

A 1924 article in National Geographic boasted that “no other nation in history has ever created a finer record in colonial administration” than the U.S. in Puerto Rico. In reality, the majority of the population lived in poverty, as corporations drove peasants off their land and turned them into ruthlessly exploited day laborers. Although leading the colonial government, Luis Muñoz Rivera of the Unionist Party was privately scathing. “Blame will fall on the landowners who abuse their workers,” he confided to a colleague. “Capital wants everything and takes it from labor. We are their accomplices because of our inexcusable silence.”

Colonial officials not only exploited the wealth but also the health of Puerto Rico, turning the island into a captive laboratory for medical research. Most notoriously, The Rockefeller Foundation hired Cornelius Rhoads, who called his Puerto Rican patients “experimental ‘animals’” while studying malnutrition.

In 1932, pro-independence supporters ignited a scandal by publishing one of his private letters. “Porto Ricans,” Rhoads wrote, “are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. What this island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population.” Rhoads claimed that he had already contributed to “the process of extermination by killing off 8.”

Despite public backlash, he escaped with his reputation intact, later receiving a flattering feature in Time magazine for his medical research.

Echoing Rhoads, most U.S. officials claimed that “overpopulation,” rather than exploitation, was the main cause of Puerto Rico’s poverty. Adopting an aggressive birth control program, they tested contraceptives on residents and eventually sterilized one-third of the female population of reproductive age. Feminists later argued that the policy constituted a form of “genocide,” since doctors forced women in labor to accept sterilizations and apparently targeted minors to meet “quotas.”

The coercive medical experiments, sprawling sugar plantations and pervasive racism of officials reflected the colonial status of Puerto Rico. For U.S. authorities, the archipelago was an “unincorporated territory” that “belong[ed] to” the U.S., but was “not a part of” it. As sociologist José Atiles-Osoria argues, Puerto Rico became a nation suspended in a permanent state of exception: a territory without sovereignty that foreign soldiers, investors and scientists exploited at will.

Outlawing the Nation

During the 1930s, a burgeoning independence movement emerged under the leadership of Pedro Albizu Campos and the Nationalist Party, which propounded Spanish-language education, workers’ rights and a clean break from the United States. A spellbinding speaker, Albizu Campos promoted international solidarity with anti-colonial forces, while backing a mass strike that immobilized the sugar industry in 1934. The previous year, the unemployment rate had hit 65 percent, dramatizing the failures of U.S. rule.

Fearing the movement’s appeal, authorities militarized the police, arming members with submachine guns, rifles and riot gear. In 1935, security forces massacred a group of independence supporters in Río Piedras returning from a political rally. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and local officials harassed and spied on independence activists in dozens of cities, imprisoning Albizu Campos and opening thousands of illegal “carpetas” (“files”) on citizens. Opposed to dissent, Gov. Blanton Winship left little room for ambiguity: “In front of the nationalists, always shoot to kill.”

Tensions peaked in March 1937, as the Nationalist Party planned a parade in Ponce commemorating the abolition of slavery. Preparing to smash the procession, Capt. Felipe Blanco ordered subordinates to bring reinforcements that “shoot well,” while Governor Winship monitored developments from a nearby farm.

As the march began, around 200 police suddenly opened fire, mowing down civilians with automatic weapons. The newspaper El País reported that streets ran with blood, giving the city “the unpleasant appearance” of “a butcher shop.” Police finished off the injured with pistol shots and billy club blows, while riddling both adult and child spectators with bullets. Ultimately, they killed 19 people and wounded about 200 others.

The Ponce massacre had an immediate chilling effect, prompting a mass exodus from the Nationalist Party, intimidating independence advocates and offering a pretext for another wave of repression. Over the following decade, Winship and his successors exploited “every mechanism at their disposal to combat, isolate, or eliminate the independence movement,” according to the Puerto Rico Civil Rights Commission.

Above all, the imprisonment of Albizu Campos reflected the ferocity of colonial policy. Despite claiming he was mentally ill, the FBI plotted to drop “a psychological bombshell” inducing “stress and strain” on him, and captors allegedly tortured the independence leader with radiation, turning his skin into a tapestry of spreading burn marks.

Ultimately, the campaign of intimidation weakened the Nationalists, and convinced other parties to withdraw support for independence altogether. Through raw violence and subtle pressure, U.S. policy makers squeezed the parameters of acceptable political debate, stigmatized dissent and convinced the local elite to respect the implicit limits of Puerto Rico’s colonial order.

The Model Police State

By the late 1940s, pressure from the United Nations and decolonizing Global South compelled the U.S. to address the most glaring features of the colonial regime. In 1950, President Harry Truman and Gov. Luis Muñoz Marín announced that Puerto Rico would become a “Free Associated State” (FAS), fostering the illusion of self-determination even as the federal government retained control over its security, trade, foreign policy, and other essential domains.

By revising the territory’s status, Washington modernized the colonial order to preserve it, allowing Puerto Ricans to elect local officials, maintain a nonvoting representative in the U.S. Congress and enjoy limited “autonomy” — giving colonialism a Puerto Rican face and democratic façade.

Gov. Muñoz Marín became the preferred collaborator of the U.S., while lobbying for the FAS and stifling political dissent. He and the FBI developed a tense yet symbiotic relationship. The historian Nelson Denis claims that the agency leveraged knowledge of his opium addiction to keep Muñoz Marín on a tight leash. Meanwhile, he manipulated its obsession with communism to muzzle his political opponents. Privately, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover mused that “Gov. Muñoz Marín wants his own banana republic, with American air conditioning.”

To discredit the FAS project, the badly battered Nationalist Party launched an uprising in October 1950. Through a dramatic confrontation, organizers hoped to expose the colonial architecture of the political system and gain international support for independence. They seized at least 10 towns and even tried to assassinate President Truman in Washington, D.C.

Authorities responded with indiscriminate fury. Soldiers leveled the towns of Jayuya and Utuado with air raids, before executing revolutionaries without a trial. Attorney General Vicente Géigel Polanco recalled that Muñoz Marín “ordered that all the nationalists in Puerto Rico were arrested.” Police ripped civilians from bed at machine-gun point, imprisoning nearly 1,000 in only two days. The list of “subversives” that they used was so broad that it included Muñoz Marín’s own wife and a future chief justice of Puerto Rico’s Supreme Court — the result of two decades of unrelenting surveillance.

Throughout the Cold War, the violent policies that drowned out the October uprising persisted, even as National Geographic and other U.S. media claimed that Puerto Rico was “a model for Latin America” and “a booming showcase of democracy.”

Repression noticeably heightened after the Cuban Revolution inspired a new generation of political activists. During the 1970s, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, Young Lords Organization, Macheteros, and other New Left groups not only promoted independence but a socialist alternative. Once more, U.S. authorities responded with a heavy hand: screening job candidates across the island, opening the mail of dissidents, and targeting critics with surveillance operations, smear campaigns and even death squads. In July 1978, police notoriously lured student activists to Cerro Maravilla before murdering them in cold blood.

The ethical compromises, political manipulation and structural violence that Muñoz Marín and the Free Associated State enshrined left a corrosive legacy. As the Cold War ended, Supreme Court Justice Antonio Negrón García admitted that law enforcement practices were “typical of a fascist terror or military dictatorships.” In the end, police compiled 16,793 dossiers and 151,541 reference cards on alleged dissidents, overwhelming the Intelligence Division’s offices and compelling officers to store files in their own homes. Puerto Rico remained in geopolitical purgatory: a colony that had missed the great drama of the 20th century, decolonization, yet could not escape the past.

Island Warlords

Since the Cold War ended, U.S. colonialism has remained a violent and inescapable reality for residents of Puerto Rico. A 2022 American Medical Association article concludes that “Colonialism is literally killing Puerto Ricans,” as the restructuring of the territory’s finances has gutted the health care system and public services. A rolling debt crisis, decades of austerity and a heavily militarized law enforcement system continue to infuse everyday life with shades of repression.

Nowhere is this clearer than Vieques, an island that the Navy historically commandeered for military exercises by bulldozing entire neighborhoods to the ground. By the late 1990s, the military occupied 75 percent of the island, while sowing its beaches with explosives. In a cruel twist, the U.S. effectively waged war against Vieques while claiming to defend it — literally bombing hills into dust. Later, government investigators concluded that shooting exercises were turning the island “into a desert,” even leading to the “disfiguration of mountains.”

Beyond “strangling” the local economy, investigators stressed, the military fostered “a culture of violence.” Rape was commonplace. Lucía Meléndez Sanes recalled that soldiers arrived in her neighborhood “looking for girls” in the evening. “You could not be outside at that hour because they behaved like animals in the street.” Parents hid their daughters, while living in constant fear. As U.S. forces occupied Afghanistan, Vieques resident Carmen Valencia emphasized that “we knew what terrorism was because of them. Because we lived in terror all the time.”

In 1999, fighter pilots accidentally bombed a local security guard, David Sanes Rodríguez, galvanizing a national movement to expel the military. Over four years, authorities arrested over 1,000 people for civil disobedience, as residents camped on shooting ranges and beaches. A government commission discovered that the military had fired depleted uranium shells, poisoned water with explosives and almost bombed the local capital, Isabel Segunda. Investigators also reported that Navy exercises routinely unleashed seismic waves that “shake educational facilities, affecting the educational process.”

Movement pressure forced the base to close in 2003, but Vieques remains a war zone. Residents still struggle to regain access to their land, while demanding the military remove decades of debris and unexploded ordnance. So far, the Pentagon has collected over 41,000 projectiles and 32,000 bombs, estimating that the monumental cleanup initiative will last until 2032.

Death by Colonialism

In many ways, U.S. policy in Vieques dramatizes broader patterns of colonial violence in Puerto Rico, as federal authorities, foreign capital and a corrupt local elite impose punitive austerity measures that destroy the economy and public sector, making the explosive power of bombs unnecessary.

For decades, the territory has struggled with unsustainable debt, and officials have responded by slashing funds for health care and education while privatizing control of the electrical grid. Puerto Rico’s colonial status vastly complicates the crisis, since the territory lacks the power to declare bankruptcy or renegotiate its financial obligations. In 2016, the Supreme Court reaffirmed in Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle that Congress possesses ultimate sovereignty over the archipelago. That same year, the federal government appointed an oversight board staffed by foreign financiers to manage its budget, rudely dispelling the illusion of Puerto Rican “autonomy.”

The results have been disastrous. Within only two years, authorities closed 438 schools, while cuts to health services have spiked rates of cardiovascular disease, mental illness and other ailments. Between 2010 and 2020, Puerto Rico lost over 10 percent of its population, as economic turmoil compels residents to emigrate — a trend that accelerated after Hurricane María devastated the archipelago in 2017.

Repeatedly, law enforcement agencies have met anti-austerity protests with brute force, recycling tactics developed to repress the independence movement. The ACLU asserts that the Puerto Rico Police Bureau is “plagued by a culture of violence” and “has run amok for years,” while the Department of Justice admits that “constitutional violations” are “pervasive and plague all levels.”

In this light, the 2024 gubernatorial election is a major milestone signifying the repudiation of the colonial order and its pervasive violence.

Until recent months, the projected winner was Jenniffer González, who has long defended austerity and police brutality against protesters, alleging that student demonstrators plot to “destroy democracy through violence.” A week before the election, a comedian at a Trump campaign claimed that Puerto Rico was “a floating island of garbage,” embarrassing González, who fervently supports the Republican leader.

By contrast, Juan Dalmau of the Puerto Rican Independence Party represents a movement that U.S. authorities have persecuted since the Ponce massacre. A lawyer, Dalmau began his career investigating the infamous police “carpetas,” before himself being arrested for protesting the military occupation of Vieques. Indeed, the historical connections run deep: At his closing campaign rally, a star-studded lineup of artists paid homage to Albizu Campos and the Nationalist Party.

Dalmau’s electoral clout shocked observers, raising serious talk of a pro-independence governor for the first time. Although he lost, the election constitutes only one chapter in an ongoing history of resistance. The Alliance and community activists continue to combat private mismanagement of the electrical grid, foreign investors and political violence — recently advocating for the formation of a Department of Human Rights.

The colonial order is exhausted yet unyielding. Suspended in political purgatory, Puerto Rico remains in but not of the U.S. — its residents creatively resisting the violence of an empire that excludes them.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

.

Jonathan Ng is a postdoctoral fellow at the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College.

No comments:

Post a Comment