OUTLAW DEEP SEA MINING

Preserving and using the deep sea: scientists call for more knowledge to enable sustainable management

Scientific report on deep-sea research sees 2025 as a decisive year for ocean health

Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel (GEOMAR)

Where does the deep sea begin? Definitions vary across science and legal frameworks. For the purposes of their joint analysis, the members of the European Marine Board’s (EMB) Deep Sea and Ocean Health Working Group defined the deep sea as the water column and seabed below 200 metres. Below this point, sunlight barely penetrates the water, and the habitat changes dramatically. According to this definition, the deep sea accounts for about 90 per cent of the ocean’s volume. Its importance for ecosystems and biodiversity is therefore immense. However, pressure on these still relatively untouched areas of our planet is growing: human activities such as oil extraction, fishing, and potential seabed mining threaten deep-sea ecosystems, while climate change is already having a negative impact.

The working group of eleven researchers has now presented its findings and ten key recommendations on the deep sea and ocean health. Under the leadership of Prof. Dr Sylvia Sander, Professor of Marine Mineral Resources at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, and Dr Christian Tamburini from the French Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO), the team produced the report, which is being launched today by the EMB in a webinar. The document emphasises, among other points, the urgent need for major investment in deep-sea research to close knowledge gaps and provide a sound scientific basis for decisions such as those concerning deep-sea mining.

“The ocean is an interconnected system stretching from the coast to the deepest depths,” says Sylvia Sander. “Of course, the deep sea cannot be considered in isolation from the photic zone or the seafloor.” Therefore, deep-sea research, use and conservation are intrinsically linked to overall ocean health.

Ten recommendations for sustainable deep-sea protection and better collaboration:

The group presents ten central measures for the sustainable protection of the deep sea:

- Effectively govern human activities in the deep sea

- Establish an international scientific committee for deep-sea sustainability and protection

- Contribute to develop and implement deep-sea Environmental Impact Assessment methodologies

- Support transdisciplinary research programs to better understand the role of the deep sea in Ocean (and human) health

- Invest in long-term monitoring in the deep sea

- Launch large-scale and long-term multidisciplinary natural sciences projects to increase knowledge of global deep-sea processes

- Support research efforts in specific critical research fields

- Enhance educational, training and research opportunities for all current and future scientists addressing their unique regional challenges

- Foster the transfer of marine technology and develop training programs

- Continue to promote the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability (FAIR) Data Principles

The deep sea: Indispensable ecosystems for life on Earth

Until the late 19th century, the idea that life could exist in the cold, dark, high-pressure depths of the ocean was met with scepticism. It was only with the onset of deep-sea research that the first living organisms were discovered there. Today, scientists know that the deep sea hosts a remarkable diversity of life forms. Complex ecosystems can be found along continental slopes, on abyssal plains or around hydrothermal vents – so-called black smokers – many of which remain poorly understood.

Knowledge gaps: Much remains unexplored

It is estimated that around 90 percent of all organisms in the deep sea are still undescribed, and their roles within ecosystems remain largely unknown. Physical oceanography also faces considerable gaps – for example, in the modelling of deep currents that are crucial for the transport of nutrients and pollutants. In marine geochemistry, little is known about how biogeochemical cycles in the deep sea are affected by human activities such as mining. For instance, scientists still lack a clear understanding of how sediment plumes from the extraction of manganese nodules spread and what long-term impacts they may have on seabed communities. Technical challenges also remain: many modern sensors and monitoring systems are not yet adequately developed for extreme depths, making it difficult to gather essential data. Closing these knowledge gaps is urgently needed to support science-based decision-making for deep-sea governance, the scientists argue.

The challenge: Threats to the deep sea from human activities

What we do know for certain is that the ocean – of which the deep sea makes up the largest part – stores vast amounts of CO₂ and heat, helping to mitigate climate change. It plays a central role in the global carbon cycle and produces more than 50 percent of the planet’s oxygen. Disruption of these functions could have serious global consequences. Preserving these ecosystem services requires strong protective measures and sustainable use strategies.

Human activities are already affecting the deep sea in many ways. Irreversible changes on human timescales – such as warming, acidification, and oxygen loss – are threatening these sensitive habitats. At the same time, overexploitation of fish stocks and non-renewable resources such as oil, gas, and minerals is jeopardising biodiversity and ecosystem functions.

Urgent action needed for ocean health

The scientists agree that 2025 is a decisive year to take action for ocean health. It is crucial to take effective measures against climate change now in order to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Sylvia Sander explains:

“Climate change is one of the most alarming threats to our life-support systems and to life on Earth itself. Combined with biodiversity loss, it could soon lead to severe and irreversible disruptions to the entire ocean – including the deep sea and ice-covered parts of the planet.”

The role of the EU: How Europe can lead the way in protecting the deep sea

The working group emphasises that Europe should take a leading role in the international protection and sustainable governance of the deep sea, particularly through existing international agreements.

“The EU could play an important role in strengthening international efforts to regulate deep-sea activities,” says Sylvia Sander. “This would require the establishment of scientific committees for deep-sea protection and the development of standardised environmental impact assessments.”

The researchers also call for secured funding of transdisciplinary research and long-term monitoring. Sylvia Sander: “We need to better understand the state of the ocean to protect and use the deep sea sustainably – where are changes becoming visible?” More research and technology are essential. “We also need to support underrepresented nations in deep-sea research and recognise science as a human right. Only then can we safeguard the health of the ocean – and the planet – for future generations.”

Publication:

Sander, S. G., Tamburini, C., Gollner, S., Guilloux, B., Pape, E., Hoving, H. J., Leroux, R., Rovere, M., Semedo, M., Danovaro, R., Narayanaswamy, B. E. (2025) Deep Sea Research and Management Needs. Muñiz Piniella, A., Kellett, P., Alexander, B., Rodriguez Perez, A., Bayo Ruiz, F., Teodosio, M. C., Heymans, J. J. [Eds.] Future Science Brief N°. 12 of the European Marine Board, Ostend, Belgium.

https://www.marineboard.eu/publications/deep-sea-research-and-management-needs

Background: European Marine Board

The European Marine Board (EMB) is a partnership of 38 organisations from 19 European countries that are active in marine research. Founded in 1995, its mission is to strengthen cooperation in European marine science and develop joint research strategies. The EMB acts as a bridge between science and policy, supports knowledge exchange, and provides recommendations to national authorities and the European Commission to advance marine research in Europe. Its members include leading oceanographic institutes, research funders, and universities with a marine focus.

Op-Ed: We Don't Know What Deep Sea Mining Would Do to the Midwater Zone

[By Alexus Cazares-Nuesser]

Picture an ocean world so deep and dark it feels like another planet – where creatures glow and life survives under crushing pressure.

This is the midwater zone, a hidden ecosystem that begins 650 feet (200 meters) below the ocean surface and sustains life across our planet. It includes the twilight zone and the midnight zone, where strange and delicate animals thrive in the near absence of sunlight. Whales and commercially valuable fish such as tuna rely on animals in this zone for food. But this unique ecosystem faces an unprecedented threat.

As the demand for electric car batteries and smartphones grows, mining companies are turning their attention to the deep sea, where precious metals such as nickel and cobalt can be found in potato-size nodules sitting on the ocean floor.

Images of marine life spotted in the midwater zone. Bucklin, et al., Marine Biology, 2021. Photos by R.R. Hopcroft and C. Clarke (University of Alaska Fairbanks) and L.P. Madin (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution), CC BY

Deep-sea mining research and experiments over the past 40 years have shown how the removal of nodules can put seafloor creatures at risk by disrupting their habitats. However, the process can also pose a danger to what lives above it, in the midwater ecosystem. If future deep-sea mining operations release sediment plumes into the water column, as proposed, the debris could interfere with animals’ feeding, disrupt food webs and alter animals’ behaviors.

As an oceanographer studying marine life in an area of the Pacific rich in these nodules, I believe that before countries and companies rush to mine, we need to understand the risks. Is humanity willing to risk collapsing parts of an ecosystem we barely understand for resources that are important for our future?

Mining the Clarion-Clipperton Zone

Beneath the Pacific Ocean southeast of Hawaii, a hidden treasure trove of polymetallic nodules can be found scattered across the seafloor. These nodules form as metals in seawater or sediment collect around a nucleus, such as a piece of shell or shark’s tooth. They grow at an incredibly slow rate of a few millimeters per million years. The nodules are rich in metals such as nickel, cobalt and manganese – key ingredients for batteries, smartphones, wind turbines and military hardware.

As demand for these technologies increases, mining companies are targeting this remote area, known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, as well as a few other zones with similar nodules around the world.

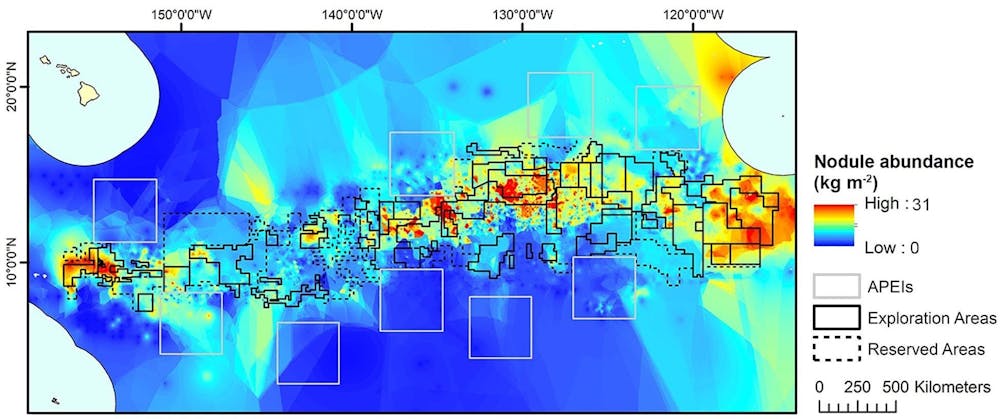

A map shows mining targets in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, southeast of Hawaii, upper left. APEIs are protected areas. McQuaid KA, Attrill MJ, Clark MR, Cobley A, Glover AG, Smith CR and Howell KL, 2020, CC BY

So far, only test mining has been carried out. However, plans for full-scale commercial mining are rapidly advancing.

Exploratory deep-sea mining began in the 1970s, and the International Seabed Authority was established in 1994 under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to regulate it. But it was not until 2022 that The Metals Company and Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. fully tested the first integrated nodule collection system in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

The companies are now planning full-scale mining operations in the region. They originally said they expected to submit their application to the ISA by June 27, 2025, but The Metals Company’s CEO announced on March 27 that he was frustrated with the pace of ISA action and was negotiating with the Trump administration for approval to mine. The U.S. is one of a handful of countries that never ratified the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which authorizes the ISA.

The ISA will convene again in July 2025 to discuss critical issues such as mining regulations, guidelines and benefit-sharing mechanisms. Several countries have called for a moratorium on seabed mining until the risks are better understood.

A visualization of a deep-sea mining operation shows two sediment plumes. Source: MIT Mechanical Engineering.

The proposed mining process is invasive. Collector vehicles scrape along the ocean floor as they scoop up nodules and stir up sediments. This removes habitats used by marine organisms and threatens biodiversity, potentially causing irreversible damage to seafloor ecosystems. Once collected, the nodules are brought up with seawater and sediments through a pipe to a ship, where they’re separated from the waste.

The leftover slurry of water, sediment and crushed nodules is then dumped back into the middle of the water column, creating plumes. While the discharge depth is still under discussion, some mining operators propose releasing the waste at midwater depths, around 4,000 feet (1,200 meters).

However, there is a critical unknown: The ocean is dynamic, constantly shifting with currents, and scientists don’t fully understand how these mining plumes will behave once released into the midwater zone.

These clouds of debris could disperse over large areas, potentially harming marine life and disrupting ecosystems. Picture a volcanic eruption – not of lava, but of fine, murky sediments expanding throughout the water column, affecting everything in its path.

The midwater ecosystem at risk

As an oceanographer studying zooplankton in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, I am concerned about the impact of deep-sea mining on this ecologically important midwater zone. This ecosystem is home to zooplankton – tiny animals that drift with ocean currents – and micronekton, which includes small fish, squid and crustaceans that rely on zooplankton for food.

Sediment plumes in the water column could harm these animals. Fine sediments could clog respiratory structures in fish and feeding structures of filter feeders. For animals that feed on suspended particles, the plumes could dilute food resources with nutritionally poor material. Additionally, by blocking light, plumes might interfere with visual cues essential for bioluminescent organisms and visual predators.

For delicate creatures such as jellyfish and siphonophores – gelatinous animals that can grow over 100 feet long – sediment accumulation can interfere with buoyancy and survival. A recent study found that jellies exposed to sediments increased their mucous production, a common stress response that is energetically expensive, and their expression of genes related to wound repair.

Additionally, noise pollution from machinery can interfere with how species communicate and navigate.

Disturbances like these have the potential to disrupt ecosystems, extending far beyond the discharge depth. Declines in zooplankton populations can harm fish and other marine animal populations that rely on them for food.

The midwater zone also plays a vital role in regulating Earth’s climate. Phytoplankton at the ocean’s surface capture atmospheric carbon, which zooplankton consume and transfer through the food chain. When zooplankton and fish respire, excrete waste, or sink after death, they contribute to carbon export to the deep ocean, where it can be sequestered for centuries. The process naturally removes planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

More research is needed

Despite growing interest in deep-sea mining, much of the deep ocean, particularly the midwater zone, remains poorly understood. A 2023 study in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone found that 88% to 92% of species in the region are new to science.

Current mining regulations focus primarily on the seafloor, overlooking broader ecosystem impacts. The International Seabed Authority is preparing to discuss key decisions on future seabed mining in July 2025, including rules and guidelines relating to mining waste, discharge depths and environmental protection.

These decisions could set the framework for large-scale commercial mining in ecologically important areas such as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Yet the consequences for marine life are not clear. Without comprehensive studies on the impact of seafloor mining techniques, the world risks making irreversible choices that could harm these fragile ecosystems.

Alexus Cazares-Nuesser is a Ph.D. candidate in biological oceanography at the University of Hawaii Manoa who studies zooplankton ecology in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a region of the Pacific considered for deep-sea mining for polymetallic nodules.

This article appears courtesy of The Conversation and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment