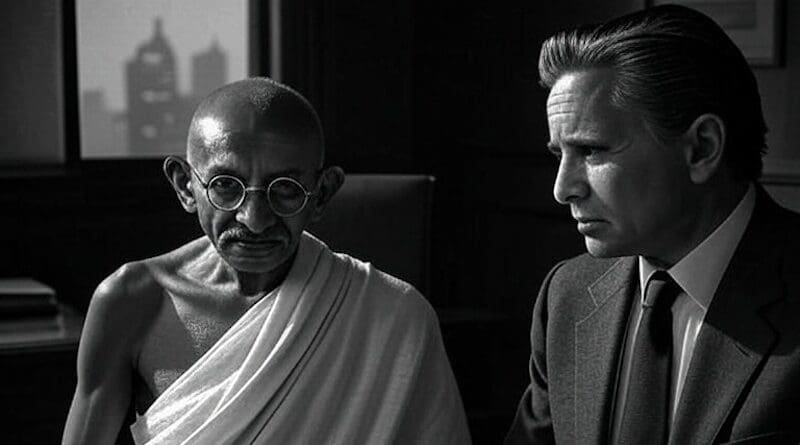

Gandhi And Gekko: Will The Twain Meet? – OpEd

Gandhi, the loincloth clad spartan Mahatma, said there’s enough in this world for everyone’s need but not enough for everyone’s greed.

The amoral and flamboyant Gordon Gekko in the 1987 Oliver Stone classic movie Wall Street flipped the script, giving a more realistic assessment of an interconnected, fast-digitalizing, post Malthus world by valorizing greed – or effort, enterprise, ambition, drive, hunger, frontier spirit, if a better euphemism is needed.

“The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed—for lack of a better word—is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms—greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge—has marked the upward surge of mankind”, said Gekko in the Teldar Paper shareholders speech. Un-ironically, the famous biography of Vincent Van Gogh, the Dutch painter, is titled Lust for Life.

This ‘better word’, which covers the gamut between the sacred and the profane, from ideologies, religions, revolutionary ardor, sacrifice, altruism, is effectively similar to Churchill’s quip on democracy – deeply flawed, but better than what’s already already been tried, over and over again.

Invisible Hand vs Clenched Fist

Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand and enlightened self-interest offers the most tangible incentives to people in the most identity-agnostic and value-neutral manner. Markets have been markedly proven to be better, more efficient, and unbiased equalizers and allocators than the motley Messiahs, or Marx, Marcuse, and Mao.

The invisible hand is always more impersonal, and by extension, equally capricious, rather than the selectively ruthless visible fist of the state.

In the movie, there’s a memorable line by Bud Fox, the Charlie Sheen character, ‘I never realised how poor I was until I started making real money’. Money is different things to different people – for the everyman it’s just an exchange token that guarantees well-being, and keeps penury and privation at bay.

For the more well-off, it’s a tool to hedge the future and insure against any uncertainties. But once these thresholds are crossed, money and what it buys, is mainly a surplus gratification. Thorstein Veblen, the Norwegian economist who coined the term Conspicuous Consumption in 1903, described it as a signalling, filtration, segregation, and psychological fulfilment mechanism.

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness is all about charting a middle path between Gandhi & Gekko, which effectively means balancing between self-reliant sustainability and hyper consumption ‘you only live once’ carpe diem. Over emphasis on the latter, or just on material value maximization, often leads to a deadlock.

Travails of ‘Zero-Sum’

There’s a funny statement that even if you end up winning the rate-race you will still be a rat. Ever wondered why then the allure of it is so strong?

Fight or flight, winner-takes-it-all, victory or surrender mindset is deeply ingrained in human thinking. It is mainly due to the frequent outbreak of diseases, war, famines in the ancient times and the looming uncertainty associated with all facets of human existence. The best insurance policy for those lacking power and pelf was either guile, patronage, luck, or god.

Anyone who has played monopoly board game as a child, written a highly competitive exam, participated in athletics, or been an Options trader, instinctively understands what a zero-sum game is – you gotta win, and you can only do it if somebody else loses. The fundamental flaw, however, is that life is way more complex than certain case-specific scenarios, and what’s narrowly applicable isn’t axiomatic.

The smartest people everywhere follow Carlo Cippola’s definition of intelligent as someone who believes in win-win, mutually beneficial outcomes, or what David Ogilvy, the founder of the namesake advertising giant, said about only hiring people smarter than you to become a company of giants.

“Zero-sum thinking can be so problematic: It pinches perspective, sharpens antagonism and distracts our minds from what we can do with cooperation and creativity. People with a zero-sum mentality can easily miss a win-win”, writes Damien Cave, the New York Times Vietnam Bureau Chief.

In his book Bullshit Jobs, the anthropologist David Graeber identifies five types of professions: flunkies, goons, duct-tapers, box-tickers, and task-masters.

Flunkies are those that hang-around someone important. Goons are enforcers or compliance departments that ensure you follow the rigmarole. Duct-tapers are hired when shit hits the fan, or to identify pain-points when there are none, or which they are not qualified to scour.

In the words of Graeber, “box tickers are employees who exist only or primarily to allow an organization to be able to claim it is doing something that, in fact, it is not doing”.

Task-masters are often the number cruncher middle management with no skin-in-the-game and lack of subject matter expertise.

Zero-sum thinking would be less rife in creative fields, science, research, or even say the roughneck world of real estate or mafia where trade-offs and compromises are a part of life. It would be more explicitly pronounced in fields where all value is contestable, abstract, subjective, and whether or not you rise up the ladder depends solely on your ability to partake in charades, performative art, and engaging in roleplay. This is the great paradox of boardroom bureaucracy.

The rise of a New Managerial class, as anticipated by James Burnham in the 1960s, which resembles Soviet urban mandarins a lot, would enhance the anger, envy, and malice associated with zero-sum thinking. On a treadmill, you ought to keep running, but you stay where you are.

New Dimension

Robert M. Solow, the MIT economist, added a new third dynamic to economics, which is more consequential than land, labour, and capital – technology.

The exponential growth through technology advancements and innovation, from the semiconductor revolution of the 1960s, to Windows and World Wide Web of the late 1990s, and the smartphone and social media revolution of the 2000s, have all played a critical role in magnifying growth and boosting production.

The top rated companies in NASDAQ, FAANG( Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) were all created in the past 20 years.

Technology has the ability to widen the net of access, reduce inequality, and broaden people’s horizons.

“Zero-sum thinking is crucial to understanding the politics and economics of America today”, writes Stefanie Stantcheva, Founder & Director, Social Economics Lab at Harvard University.

“This way of thinking doesn’t just appear out of nowhere; it stems from people’s economic environment and experiences—not only their own, but also those of their families and even earlier generations”, she adds.

Technology, access, abundance, and inclusive institutions have the power to break these recurring traumatic patterns of the inherited neuroticism and gradually instill new behaviours and modes of thinking.

- The past is never dead. It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity. ~ William Faulkner

Aditya Chaturvedi

Aditya Chaturvedi is a keen observer of geopolitics, with an avid interest in the intersection of society, politics, pop culture, technology, and history.

No comments:

Post a Comment