Paris Agreement turns 10 as heat rises faster than global action

Ten years after the Paris Agreement was signed on 12 December 2015, the world is warming faster than countries are cutting emissions – even as clean energy expands and projected future warming has fallen.

Issued on: 12/12/2025 - RFI

Rising heat, rising losses

Each year since the Paris deal has been hotter than 2015.

Deadly heat waves have struck India, the Middle East, the Pacific Northwest and Siberia. Wildfires have burned across Hawaii, California, Europe and Australia. Severe floods have hit Pakistan, China and the American South.

Researchers say many of these disasters show signs of human-driven warming.

More than 7 trillion tonnes of ice have melted from glaciers and the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets since 2015. Sea levels have risen by 40 millimetres over the decade.

Research in medical journal The Lancet warns global economic losses tied to extreme weather reached about $304 billion last year.

Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a record 53.2 gigatons last year. Two-thirds came from China, the United States, the European Union, India, Russia, Indonesia, Brazil and Japan. Only the EU and Japan cut their annual totals.

Green power

The past decade has seen progress in other respects, notably renewable energy.

Renewables now supply 40 percent of global electricity and overtook coal in the first half of the year, with wind and solar covering all new demand.

According to UN assessments cited in expert analyses, solar is now 41 percent cheaper than fossil fuels and onshore wind is 53 percent cheaper. Clean-energy investment surpassed $2 trillion in 2024, double fossil-fuel spending.

Electric vehicle sales have climbed from about 1 percent of global car sales in 2015 to nearly a quarter.

“There’s no stopping it,” said Todd Stern, a former US special climate envoy who helped negotiate the Paris deal. “You cannot hold back the tides.”

Yet fossil fuels still supply about 80 percent of global energy, the same share as in 2015.

A narrowing window

Without the Paris deal, scientists say the world may have headed for about 4C of warming by 2100.

Existing national plans point to roughly 2.3C to 2.5C if fully delivered. Current pledges would cut emissions by about 10 percent between 2019 and 2035.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN’s climate science body, says they need to fall by 60 percent by 2035 to keep the 1.5C limit in reach.

Developed countries pledged $300 billion a year by 2035 at Cop29 in Baku last year, far below what developing nations say they need.

“The Paris Agreement itself has underperformed,” said Joanna Depledge, a climate negotiations historian at the University of Cambridge.

“Unfortunately, it is one of those half-full, half-empty situations where you can’t say it’s failed. But then nor can you say it’s dramatically succeeded.”

(with newswires)

Ten years after the Paris Agreement was signed on 12 December 2015, the world is warming faster than countries are cutting emissions – even as clean energy expands and projected future warming has fallen.

Issued on: 12/12/2025 - RFI

The Eiffel tower lit up in green with with the words "Paris Agreement is done" to celebrate the UN accord reached at the 2015 Cop21 climate summit in Paris. © REUTERS/Jacky Naegelen/File Photo

Earth has warmed by about 0.46C since the deal was signed and the past decade has been the hottest on record. Scientists say governments have not moved fast enough to break dependence on coal, oil and gas, even though the accord has helped lower long-term temperature forecasts.

Johan Rockstrom, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research, warned that the gap between action and impacts has grown as temperatures continue to rise and extreme weather intensifies.

“I think it’s important that we’re honest with the world and we declare failure,” he said, adding that climate harms are arriving faster and more severely than expected.

Other voices point to progress the agreement has helped drive. Former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres said momentum has exceeded expectations.

“We’re actually in the direction that we established in Paris at a speed that none of us could have predicted,” Figueres said. The pace of worsening weather, she added, now outstrips efforts to cut emissions.

UN agencies have also warned that the world is not keeping up. UN Environment Programme head Inger Andersen said the world is “obviously falling behind”.

“We’re sort of sawing the branch on which we are sitting,” Andersen said.

Earth has warmed by about 0.46C since the deal was signed and the past decade has been the hottest on record. Scientists say governments have not moved fast enough to break dependence on coal, oil and gas, even though the accord has helped lower long-term temperature forecasts.

Johan Rockstrom, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research, warned that the gap between action and impacts has grown as temperatures continue to rise and extreme weather intensifies.

“I think it’s important that we’re honest with the world and we declare failure,” he said, adding that climate harms are arriving faster and more severely than expected.

Other voices point to progress the agreement has helped drive. Former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres said momentum has exceeded expectations.

“We’re actually in the direction that we established in Paris at a speed that none of us could have predicted,” Figueres said. The pace of worsening weather, she added, now outstrips efforts to cut emissions.

UN agencies have also warned that the world is not keeping up. UN Environment Programme head Inger Andersen said the world is “obviously falling behind”.

“We’re sort of sawing the branch on which we are sitting,” Andersen said.

Rising heat, rising losses

Each year since the Paris deal has been hotter than 2015.

Deadly heat waves have struck India, the Middle East, the Pacific Northwest and Siberia. Wildfires have burned across Hawaii, California, Europe and Australia. Severe floods have hit Pakistan, China and the American South.

Researchers say many of these disasters show signs of human-driven warming.

More than 7 trillion tonnes of ice have melted from glaciers and the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets since 2015. Sea levels have risen by 40 millimetres over the decade.

Research in medical journal The Lancet warns global economic losses tied to extreme weather reached about $304 billion last year.

Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a record 53.2 gigatons last year. Two-thirds came from China, the United States, the European Union, India, Russia, Indonesia, Brazil and Japan. Only the EU and Japan cut their annual totals.

Green power

The past decade has seen progress in other respects, notably renewable energy.

Renewables now supply 40 percent of global electricity and overtook coal in the first half of the year, with wind and solar covering all new demand.

According to UN assessments cited in expert analyses, solar is now 41 percent cheaper than fossil fuels and onshore wind is 53 percent cheaper. Clean-energy investment surpassed $2 trillion in 2024, double fossil-fuel spending.

Electric vehicle sales have climbed from about 1 percent of global car sales in 2015 to nearly a quarter.

“There’s no stopping it,” said Todd Stern, a former US special climate envoy who helped negotiate the Paris deal. “You cannot hold back the tides.”

Yet fossil fuels still supply about 80 percent of global energy, the same share as in 2015.

A narrowing window

Without the Paris deal, scientists say the world may have headed for about 4C of warming by 2100.

Existing national plans point to roughly 2.3C to 2.5C if fully delivered. Current pledges would cut emissions by about 10 percent between 2019 and 2035.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN’s climate science body, says they need to fall by 60 percent by 2035 to keep the 1.5C limit in reach.

Developed countries pledged $300 billion a year by 2035 at Cop29 in Baku last year, far below what developing nations say they need.

“The Paris Agreement itself has underperformed,” said Joanna Depledge, a climate negotiations historian at the University of Cambridge.

“Unfortunately, it is one of those half-full, half-empty situations where you can’t say it’s failed. But then nor can you say it’s dramatically succeeded.”

(with newswires)

As the Paris climate deal turns 10 on Friday, its promise of holding global warming to between 1.5C and 2C is slipping further out of reach. Adelle Thomas, a geographer from the Bahamas and one of 600 scientists from the UN’s climate panel drafting the next global assessment, told RFI that political pushback is getting in the way of meaningful action on an "existential" threat.

Issued on: 12/12/2025 - RFI

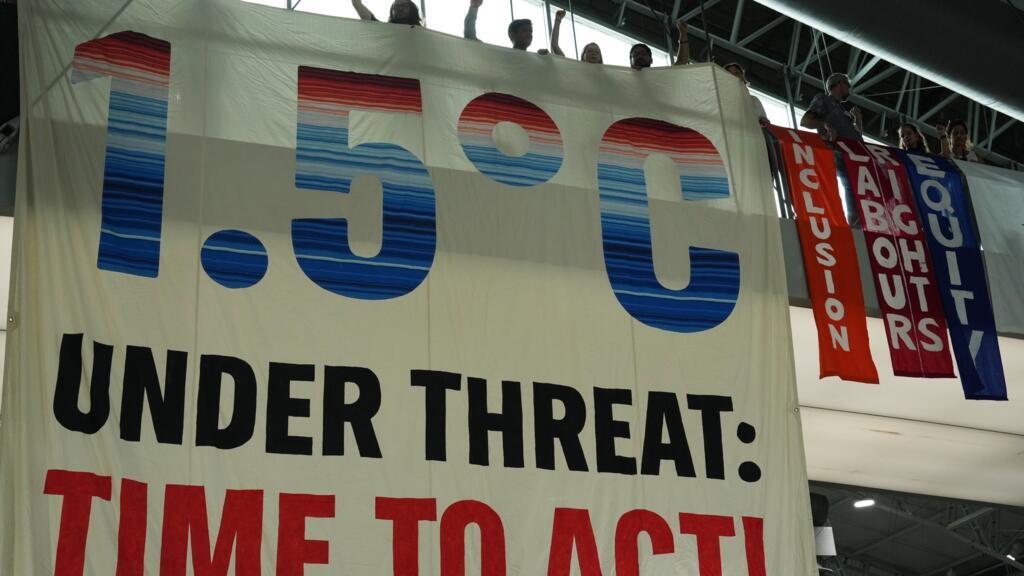

Activists demonstrate at the Cop30 climate summit in Belem, Brazil, on 21 November 2025. © AP - Andre Penner

RFI: The 1.5C threshold has divided governments. Some say it is unattainable, while others see it as political. Small island states defend it strongly. As a scientist and an islander, how do you see it?

Adelle Thomas: The 1.5C threshold is critical for small islands. The special IPCC report showed clearly and unequivocally that risks rise sharply as we pass 1.5C, especially for small islands and least developed countries. Going beyond 1.5C could even make some islands unable to exist in the future, particularly because of sea level rise.

RFI: Can you give an example for the Bahamas?

AT: We rely heavily on coral reefs. They protect our shores from erosion and storms. At 1.5C, about 90 percent of coral reefs may die. At 2C, that rises to 99 percent. It is serious at 1.5C and becomes existential at 2C.

For sea level rise, going past 1.5C means several metres of rise over the coming centuries. In the far future, the sea could be high enough to cover our islands.

In 2019 Hurricane Dorian was the most intense storm ever to hit the Bahamas. It completely destroyed my grandparents’ house. Only a toilet was left standing. The mangroves on their property were destroyed and have not recovered. Their settlement has still not recovered six years later.

It shows how destructive these hurricanes have become and how long recovery takes. Some communities never recover. This is why 1.5C matters so much for underserved communities.

You also see the effects in everyday life: stronger hurricanes, severe coastal erosion, beaches that have vanished, and homes that are repeatedly flooded and losing value. The impacts are already clear.

RFI: The 1.5C threshold has divided governments. Some say it is unattainable, while others see it as political. Small island states defend it strongly. As a scientist and an islander, how do you see it?

Adelle Thomas: The 1.5C threshold is critical for small islands. The special IPCC report showed clearly and unequivocally that risks rise sharply as we pass 1.5C, especially for small islands and least developed countries. Going beyond 1.5C could even make some islands unable to exist in the future, particularly because of sea level rise.

RFI: Can you give an example for the Bahamas?

AT: We rely heavily on coral reefs. They protect our shores from erosion and storms. At 1.5C, about 90 percent of coral reefs may die. At 2C, that rises to 99 percent. It is serious at 1.5C and becomes existential at 2C.

For sea level rise, going past 1.5C means several metres of rise over the coming centuries. In the far future, the sea could be high enough to cover our islands.

In 2019 Hurricane Dorian was the most intense storm ever to hit the Bahamas. It completely destroyed my grandparents’ house. Only a toilet was left standing. The mangroves on their property were destroyed and have not recovered. Their settlement has still not recovered six years later.

It shows how destructive these hurricanes have become and how long recovery takes. Some communities never recover. This is why 1.5C matters so much for underserved communities.

You also see the effects in everyday life: stronger hurricanes, severe coastal erosion, beaches that have vanished, and homes that are repeatedly flooded and losing value. The impacts are already clear.

Adelle Thomas, a human-environment geographer, lead author of the IPCC Special Report on 1.5C and vice-chair of the IPCC's Working Group II, pictured in Paris on 4 December 2025. © Géraud Bosman-Delzons/RFI

RFI: At the latest climate talks, the role of science became a point of tension. What happened?

AT: This Cop was very contentious about the role of science. Some countries questioned whether the IPCC should continue to be referred to as the best available science. Others tried to undermine the science altogether.

It reflects what we see in places where leaders discount science and climate change. These attacks often aim to weaken the pressure to cut emissions. Countries that know the science is real, that see the impacts and know they must act, need to push back.

RFI: The US administration has also blocked federal agencies from contributing to the next report. Does that affect your work?

AT: Yes. The US National Climate Assessment, which normally informs the North America chapter, has been cancelled. Without it, we have fewer studies to assess and a less complete picture of what is happening in the United States and in places where the US funds research. If the report were being written today, it would be a major gap, though other publications may eventually fill it.

'Climate whiplash': East Africa caught between floods and drought

RFI: Should carbon capture and storage be deployed at scale to keep the 1.5C goal alive?

AT: Carbon capture and storage is complicated. There are negative effects. In the report we will identify the trade-offs and benefits and assess whether it does more harm than good. I cannot say whether we should or should not deploy it, but it is essential that if we overshoot 1.5C we come back below it.

RFI: So technology will be essential?

AT: It may be, but there are other pathways that do not rely on it. These are political choices. Do we want to get rid of fossil fuels? Do we want electric vehicles? Do we want better energy efficiency? There are many things we can do to change behaviour and how we use and produce energy rather than relying on new technologies alone.

RFI: Is capitalism compatible with fighting global warming?

AT: I do not think it is. Our economic models and our way of interacting with nature have brought us to this crisis. If we do not rethink how we behave, we will keep going in the same direction. That is why this IPCC cycle is bringing in indigenous and local knowledge, which offers different ways of seeing the world beyond consume and discard.

Experts come from everywhere, so there is no single view. This is my personal view. The IPCC assesses what is in the literature, and there is a lot of research on this.

Cameroon's indigenous Baka sing to save their vanishing forest home

RFI: Has the Paris Agreement failed or should we see the glass as half full?

AT: As a small islander, it is hard to see the glass as half full when water is drowning our communities. We have known for decades that global warming would hit those who contributed least to the crisis.

The Paris Agreement has bent the curve but it is not enough. We need to put our actions behind the political and flowery statements in the Agreement. We need political will to meet 1.5C.

RFI: Cop30 was meant to put adaptation at the centre. Did it meet your expectations?

AT: Personally, no. I am glad there is a new goal on adaptation finance, but developing countries wanted it by 2030. It will only be in place by 2035, which delays funding. It is a compromise.

And the basis for tripling adaptation finance is vague. Negotiations changed the language of indicators that experts had spent two years developing, making some of them unusable. Now we have another two-year process to try to make them useful. It is one step forward and half a step back.

RFI: You work in US political life. What is the atmosphere like in Congress under an administration at war with climate science?

AT: It is very sombre and very uncertain. Environmental protections that help people and nature are being rolled back in favour of oil and gas. It is disheartening to see safeguards that NGOs spent decades building being dismantled. The silver lining is at state and local level. Cities and states still have powers, and we focus on helping them push climate action.

This administration is temporary. I would not say I am optimistic, but I am neutral. Everything is temporary, including this administration.

International climate experts gather in Paris to begin 7th UN report

RFI: Some said at Cop30 that multilateralism has won. Do you agree?

AT: We did reach an agreement. It was not very ambitious, but it was an agreement.

Multilateralism has highs and lows. If we keep moving in a generally positive direction, even with small steps, that is progress.

RFI: Could you explain tipping points and what overshooting 1.5C might mean?

AT: We need more research on tipping points, when they might occur and whether they can be avoided if we go over 1.5C and come back. A major concern is tipping points in the cryosphere that could lead to multi-metre sea level rise in the far future.

The sixth assessment report showed this is an area of high uncertainty because there is not enough literature to say exactly when a tipping point is reached. There is so much money put into researching these questions. If we put as much money and attention into not exceeding 1.5C or coming back down, that would be even more useful.

This interview by RFI's Géraud Bosman-Delzons has been lightly edited for clarity.

RFI: At the latest climate talks, the role of science became a point of tension. What happened?

AT: This Cop was very contentious about the role of science. Some countries questioned whether the IPCC should continue to be referred to as the best available science. Others tried to undermine the science altogether.

It reflects what we see in places where leaders discount science and climate change. These attacks often aim to weaken the pressure to cut emissions. Countries that know the science is real, that see the impacts and know they must act, need to push back.

RFI: The US administration has also blocked federal agencies from contributing to the next report. Does that affect your work?

AT: Yes. The US National Climate Assessment, which normally informs the North America chapter, has been cancelled. Without it, we have fewer studies to assess and a less complete picture of what is happening in the United States and in places where the US funds research. If the report were being written today, it would be a major gap, though other publications may eventually fill it.

'Climate whiplash': East Africa caught between floods and drought

RFI: Should carbon capture and storage be deployed at scale to keep the 1.5C goal alive?

AT: Carbon capture and storage is complicated. There are negative effects. In the report we will identify the trade-offs and benefits and assess whether it does more harm than good. I cannot say whether we should or should not deploy it, but it is essential that if we overshoot 1.5C we come back below it.

RFI: So technology will be essential?

AT: It may be, but there are other pathways that do not rely on it. These are political choices. Do we want to get rid of fossil fuels? Do we want electric vehicles? Do we want better energy efficiency? There are many things we can do to change behaviour and how we use and produce energy rather than relying on new technologies alone.

RFI: Is capitalism compatible with fighting global warming?

AT: I do not think it is. Our economic models and our way of interacting with nature have brought us to this crisis. If we do not rethink how we behave, we will keep going in the same direction. That is why this IPCC cycle is bringing in indigenous and local knowledge, which offers different ways of seeing the world beyond consume and discard.

Experts come from everywhere, so there is no single view. This is my personal view. The IPCC assesses what is in the literature, and there is a lot of research on this.

Cameroon's indigenous Baka sing to save their vanishing forest home

RFI: Has the Paris Agreement failed or should we see the glass as half full?

AT: As a small islander, it is hard to see the glass as half full when water is drowning our communities. We have known for decades that global warming would hit those who contributed least to the crisis.

The Paris Agreement has bent the curve but it is not enough. We need to put our actions behind the political and flowery statements in the Agreement. We need political will to meet 1.5C.

RFI: Cop30 was meant to put adaptation at the centre. Did it meet your expectations?

AT: Personally, no. I am glad there is a new goal on adaptation finance, but developing countries wanted it by 2030. It will only be in place by 2035, which delays funding. It is a compromise.

And the basis for tripling adaptation finance is vague. Negotiations changed the language of indicators that experts had spent two years developing, making some of them unusable. Now we have another two-year process to try to make them useful. It is one step forward and half a step back.

RFI: You work in US political life. What is the atmosphere like in Congress under an administration at war with climate science?

AT: It is very sombre and very uncertain. Environmental protections that help people and nature are being rolled back in favour of oil and gas. It is disheartening to see safeguards that NGOs spent decades building being dismantled. The silver lining is at state and local level. Cities and states still have powers, and we focus on helping them push climate action.

This administration is temporary. I would not say I am optimistic, but I am neutral. Everything is temporary, including this administration.

International climate experts gather in Paris to begin 7th UN report

RFI: Some said at Cop30 that multilateralism has won. Do you agree?

AT: We did reach an agreement. It was not very ambitious, but it was an agreement.

Multilateralism has highs and lows. If we keep moving in a generally positive direction, even with small steps, that is progress.

RFI: Could you explain tipping points and what overshooting 1.5C might mean?

AT: We need more research on tipping points, when they might occur and whether they can be avoided if we go over 1.5C and come back. A major concern is tipping points in the cryosphere that could lead to multi-metre sea level rise in the far future.

The sixth assessment report showed this is an area of high uncertainty because there is not enough literature to say exactly when a tipping point is reached. There is so much money put into researching these questions. If we put as much money and attention into not exceeding 1.5C or coming back down, that would be even more useful.

This interview by RFI's Géraud Bosman-Delzons has been lightly edited for clarity.

No comments:

Post a Comment