A "ghost" cargo ship has washed up off the coast of County Cork, Ireland, brought in by the bad weather that lashed Europe in Storm Dennis.

The abandoned boat was spotted on the rocks of fishing village Ballycotton by a passerby.

The vessel appears to have drifted thousands of miles over more than a year, from the south-east of Bermuda in 2018, across the Atlantic Ocean.

"This is one in a million," said local lifeboat chief John Tattan.

The head of Ballycotton's Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) told the Irish Examiner newspaper he had "never, ever seen anything abandoned like that before."

So what's the story behind this mysterious ship without a crew?

Rescue 117 was tasked earlier today to a vessel aground near Ballycotton, Cork. There was nobody on board. Previously the @USCG had rescued the 10 crew members from the vessel back in September 2018. The vessel has been drifting since and today came ashore on the Cork coastline. pic.twitter.com/NbvlZ89KSY— Irish Coast Guard (@IrishCoastGuard) February 16, 2020

An abandoned ship washed up on the rocky shore of southern Ireland after having drifted across the Atlantic Ocean for more than a year, the Irish Coast Guard said Monday.

Wind of up to 110 kilometers (70 miles) per hour from Storm Dennishad pushed the "ghost ship" towards the Irish coast. It was first sighted on Sunday.

The coast guard identified the 77-meter (250-feet) cargo ship as the MV Alta, which broke down while sailing from Greece to Haiti in September 2018.

The US Coast Guard rescued 10 people from the broken down vessel 1,380 miles (2,220 kilometers) southeast of the Atlantic archipelago Bermuda.

The crew had spent 20 days onboard the ship, having been supplied with food by the coast guard before they were rescAn abandoned ship washed up on the rocky shore of southern Ireland after having drifted across the Atlantic Ocean ued.

The ship was last spotted drifting crewless in the mid-Atlantic by a British patrol ship in August 2019.

Cork county officials said Monday that there was no sign of pollution from the 44-year-old ship, and a contractor would board the vessel at low tide on Tuesday for further assessment of what to do with the wreck.

WHICH OF COURSE WILL REMIND THE PERCEPTIVE READER OF IRISH GOTHIC FICTION OF THIS

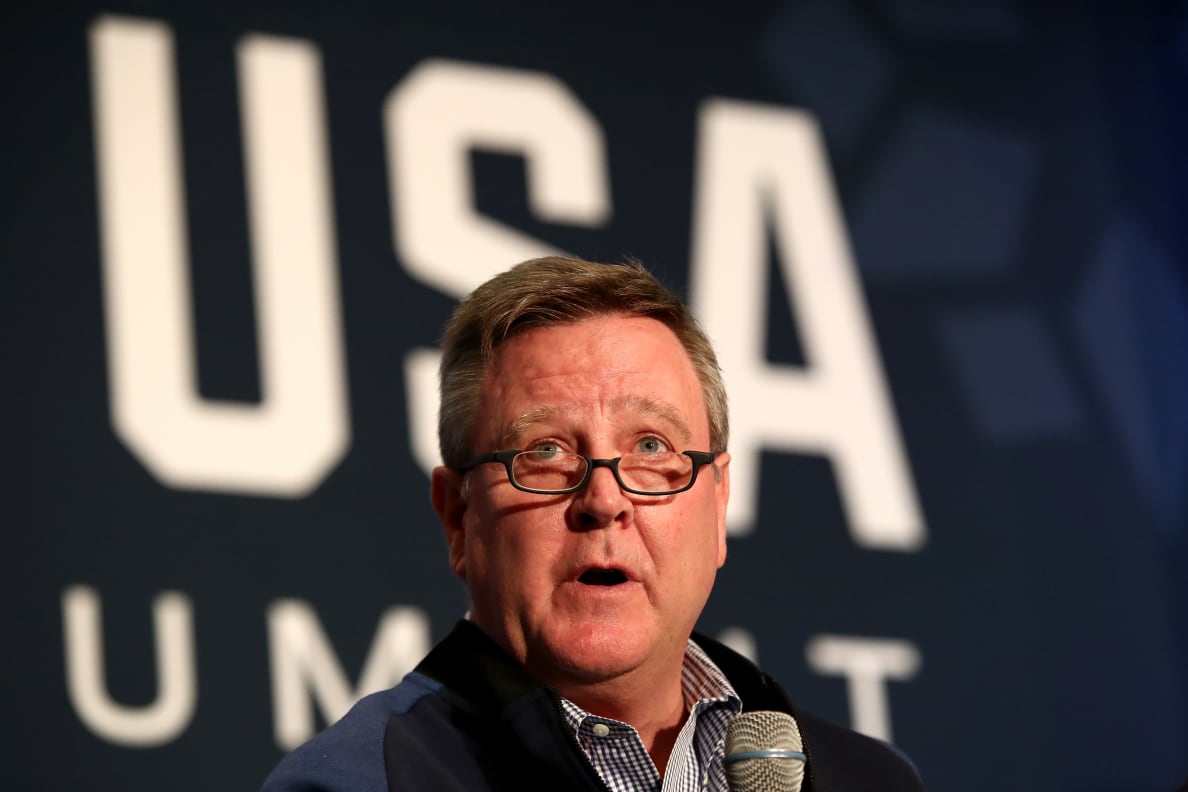

Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula, published in May 1897, is one of the outstanding works of Gothic literature. The story, told in the form of letters and journal entries, tapped into the fears that haunted the Victorian fin de siècle. In Dracula, modern, progressive Britain is menaced by decayed, aristocratic Europe. Superstition is pitted against science, and wanton female sexuality, in the guise of Lucy Westenra, is contrasted with the traditional respectability of Mina Murray. The book is an imaginative tour de force, full of terrifying and dream-like imagery, but its roots lie deep in the anxieties of late-Victorian Britain.

DRACULA

Summary and Analysis Chapters 7-8

Summary

Utilizing the narrative device of a newspaper clipping (dated August 8th), the story of the landing of Count Dracula's ship is presented. The report indicates that the recent storm, one of the worst storms on record, was responsible for the shipwreck of a strange Russian vessel. The article also mentions several observations which indicate the vessel's strange method of navigation; we learn that observers feel that the captain had to be mad because in the midst of the storm the ship's sails were wholly unfurled.

Many people who witnessed the approach of the strange vessel were gathered on one of Whitby's piers to await the ship's arrival. By the light of a spotlight, witnesses noticed that "lashed to the helm was a corpse, with drooping head, which swung horribly to and fro" as the ship rocked. As the vessel violently ran aground, "an immense dog sprang up on deck from below," jumped from the ship, and ran off. Upon closer inspection, it was discovered that the man lashed to the wheel (the helm) had a crucifix clutched in his hand. According to a local doctor, the man had been dead for at least two days. Coast Guard officials discovered a bottle in the dead man's pocket, carefully sealed, which contained a roll of paper.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 15 (Autumn 2016)4 Dracula’s Gothic Ship

Emily Alder

The narrative of Dracula (1897) is extensively informed by Bram Stoker’s research into travel, science, literature, and folklore.1 However, one feature of the novel that has never been examined in any detail is its gothic ship, the Demeter, which transports the vampire to Whitby. The Demeter is a capstone to a long tradition of nautical and maritime gothicity in literature and legend. Gothic representations of storms, shipwrecks, and traumatic journeys were shaped and inspired by the natural power of the sea and its weather, and by the reports and experiences of those who braved the dangers of ocean travel and witnessed its sublime marvels, or stood watching on the shore. The ships of Victorian fiction, more specifically, also belong to a maritime context that was distinct to the nineteenth century and that would soon change irrevocably as the Age of Sail finally drew to a close in the early 1900s.

DRACULA

CHAPTER 7

CUTTING FROM "THE DAILYGRAPH", 8 AUGUST

(PASTED IN MINA MURRAY'S JOURNAL)

From a correspondent.

Whitby.

One of the greatest and suddenest storms on record has just been experienced here, with results both strange and unique. The weather had been somewhat sultry, but not to any degree uncommon in the month of August. Saturday evening was as fine as was ever known, and the great body of holiday-makers laid out yesterday for visits to Mulgrave Woods, Robin Hood's Bay, Rig Mill, Runswick, Staithes, and the various trips in the neighborhood of Whitby. The steamers Emma and Scarborough made trips up and down the coast, and there was an unusual amount of `tripping' both to and from Whitby. The day was unusually fine till the afternoon, when some of the gossips who frequent the East Cliff churchyard, and from the commanding eminence watch the wide sweep of sea visible to the north and east, called attention to a sudden show of `mares tails' high in the sky to the northwest. The wind was then blowing from the south-west in the mild degree which in barometrical language is ranked `No. 2, light breeze.'

The coastguard on duty at once made report, and one old fisherman, who for more than half a century has kept watch on weather signs from the East Cliff, foretold in an emphatic manner the coming of a sudden storm. The approach of sunset was so very beautiful, so grand in its masses of splendidly coloured clouds, that there was quite an assemblage on the walk along the cliff in the old churchyard to enjoy the beauty. Before the sun dipped below the black mass of Kettleness, standing boldly athwart the western sky, its downward way was marked by myriad clouds of every sunset colour, flame, purple, pink, green, violet, and all the tints of gold, with here and there masses not large, but of seemingly absolute blackness, in all sorts of shapes, as well outlined as colossal silhouettes. The experience was not lost on the painters, and doubtless some of the sketches of the `Prelude to the Great Storm' will grace the R. A and R. I. walls in May next.

More than one captain made up his mind then and there that his `cobble' or his `mule', as they term the different classes of boats, would remain in the harbour till the storm had passed. The wind fell away entirely during the evening, and at midnight there was a dead calm, a sultry heat, and that prevailing intensity which, on the approach of thunder, affects persons of a sensitive nature.

There were but few lights in sight at sea, for even the coasting steamers, which usually hug the shore so closely, kept well to seaward, and but few fishing boats were in sight. The only sail noticeable was a foreign schooner with all sails set, which was seemingly going westwards. The foolhardiness or ignorance of her officers was a prolific theme for comment whilst she remained in sight, and efforts were made to signal her to reduce sail in the face of her danger. Before the night shut down she was seen with sails idly flapping as she gently rolled on the undulating swell of the sea.

"As idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean."

D R A C U L A

by

Bram Stoker

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers

Bram Stoker

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers

Copyright, 1897, in the United States of America, according

to Act of Congress, by Bram Stoker

[All rights reserved.]

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N.Y.

to Act of Congress, by Bram Stoker

[All rights reserved.]

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N.Y.

How American vampires wrecked a Russian ghost ship

Maybe

Last week I dealt with the strange tale of the vampire sailor, James Brown, who’s death sentence was commuted by President Andrew Johnson.

James Brown, you may remember from my earlier blog, murdered a crew mate in 1866, perhaps in self defense, perhaps not. Nearly twenty years later, he became a vampire-in-retrospect when the story grew from a single murder with a knife to several murders wherein blood was drained from his victims. This embellished version of James Brown may have originated with newspapers or it may have been the work of his prison warden, done with the intent of attracting tourists (yes, really).

Scoring some political points probably didn’t hurt.

James Brown, you may remember from my earlier blog, murdered a crew mate in 1866, perhaps in self defense, perhaps not. Nearly twenty years later, he became a vampire-in-retrospect when the story grew from a single murder with a knife to several murders wherein blood was drained from his victims. This embellished version of James Brown may have originated with newspapers or it may have been the work of his prison warden, done with the intent of attracting tourists (yes, really).

Scoring some political points probably didn’t hurt.

It’s not bad journalism, it’s just balanced

The tale seems, on it’s surface, to be a free-standing bit of American vampire lore, disconnected from the large body of European Victorian literature that gave us the popular images we now immediately recognize as vampire. It might as well be Seinfeld for as much as it resembles gothic horror.

But maybe not. Maybe there’s a Dracula connection.

The same, vampirically-enhanced version of the James Brown story reemerged in newspapers in 1892. That’s shortly before a certain Bram Stoker toured America, and he’s known to have clipped articles from several papers concerning vampires. Is it possible he caught wind of the “improved” James Brown story before he wrote his masterpiece, Dracula?

The tale seems, on it’s surface, to be a free-standing bit of American vampire lore, disconnected from the large body of European Victorian literature that gave us the popular images we now immediately recognize as vampire. It might as well be Seinfeld for as much as it resembles gothic horror.

But maybe not. Maybe there’s a Dracula connection.

The same, vampirically-enhanced version of the James Brown story reemerged in newspapers in 1892. That’s shortly before a certain Bram Stoker toured America, and he’s known to have clipped articles from several papers concerning vampires. Is it possible he caught wind of the “improved” James Brown story before he wrote his masterpiece, Dracula?

Just the facts, Bram

“So what?” you ask, not trusting me and moving on. “We know Bram Stoker researched Dracula meticulously, so what difference does it make if he noticed this story too? What bearing does this one story have?”

Wellllllll,

It just so happens that James Brown’s vessel, The Atlantic, suffered a massive shipwreck in 1887, “one of the most melancholy and disastrous wrecks of the year”, killing most of the crew.

“Surrounded by the impenetrable fog and darkness, with the spars and rigging tumbling about their heads, the stout timbers crunching and splitting like matchwood, and the ceaseless roar and turmoil of the surf as it swept the wreck from one end to the other, the situation was appallingly dreadful, and many of the crew were doubtless killed outright…”

Quick, was that description from the wreck of The Atlantic… or was it Bram Stoker’s description of the wreck of The Demeter, the schooner that crashed into Whitby, delivering Dracula to England?

“So what?” you ask, not trusting me and moving on. “We know Bram Stoker researched Dracula meticulously, so what difference does it make if he noticed this story too? What bearing does this one story have?”

Wellllllll,

It just so happens that James Brown’s vessel, The Atlantic, suffered a massive shipwreck in 1887, “one of the most melancholy and disastrous wrecks of the year”, killing most of the crew.

“Surrounded by the impenetrable fog and darkness, with the spars and rigging tumbling about their heads, the stout timbers crunching and splitting like matchwood, and the ceaseless roar and turmoil of the surf as it swept the wreck from one end to the other, the situation was appallingly dreadful, and many of the crew were doubtless killed outright…”

Quick, was that description from the wreck of The Atlantic… or was it Bram Stoker’s description of the wreck of The Demeter, the schooner that crashed into Whitby, delivering Dracula to England?

On the left, The Demeter. On the right, a barque similar to

The Atlantic. Or is it the other way around?

Author Robert Damon Schneck draws the line between a tragic wreck of a ship upon the shore, a ship that once carried a “vampire” aboard who feasted on the crew, and Dracula’s preying upon the crew of the Demeter, leaving it lifeless as it wrecked upon the rocks of Whitby. It’s a tantalizing possibility, even without corroborating notes.

Perhaps there’s a line to be drawn from American mythology and fake news to the ultimate gothic horror novel. Or perhaps it’s an astonishing coincidence. But how does anyone see the similarities and not marvel at the world we live in, full of fiction, fact, and fantastic hybrids of the two?

Author Robert Damon Schneck draws the line between a tragic wreck of a ship upon the shore, a ship that once carried a “vampire” aboard who feasted on the crew, and Dracula’s preying upon the crew of the Demeter, leaving it lifeless as it wrecked upon the rocks of Whitby. It’s a tantalizing possibility, even without corroborating notes.

Perhaps there’s a line to be drawn from American mythology and fake news to the ultimate gothic horror novel. Or perhaps it’s an astonishing coincidence. But how does anyone see the similarities and not marvel at the world we live in, full of fiction, fact, and fantastic hybrids of the two?

Things We Saw Today: We’re Getting a New Spin on Dracula With The Last Voyage of the Demeter

By Kate Gardner Oct 1st, 2019

Fans of Bram Stoker’s original novel Dracula will recognize this title. Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark director André Øvredal is in negotiations to captain The Last Voyage of the Demeter, a project inspired by the classic vampire novel. The film will follow the ship that transports Dracula from Transylvania to England, and the murderous havoc he wreaks on the crew. The project has been stuck in development hell for a while, but now has found new life.

The section on the Demeter’s fateful journey, told via the captain’s log, is one of the creepiest parts of Stoker’s novel. The slow burn of tension and the lack of places to escape—after all, where do you run on the open ocean—all build towards a horrifying climax. By focusing on this part of the tale rather than trying to spin Dracula as a romantic hero or just adapting the novel in full, the story can stay fresh and deliver a one setting horror film. Think Alien but on an old timey ship.

This news is perfectly timed to catapult the Halloween season. Vampires need a good comeback, and this could be a chance to make a really scary Dracula project. I can’t wait to see how it develops, and if this time the film makes it past the troubled waters of development hell into the hopefully smoother sailing of production and release.

(via The Hollywood Reporter, image: Universal)

HOW DRACULA CAME TO WHITBY

How Bram Stoker’s visit to the harbour town of Whitby on the Yorkshire coast in 1890 provided him with atmospheric locations for a Gothic novel – and a name for his famous vampire.

The dramatic ruins of Whitby Abbey, on the headland overlooking the town

A GOTHIC SETTING

Bram Stoker arrived at Mrs Veazey’s guesthouse at 6 Royal Crescent, Whitby, at the end of July 1890. As the business manager of actor Henry Irving, Stoker had just completed a gruelling theatrical tour of Scotland. It was Irving who recommended Whitby, where he’d once run a circus, as a place to stay. Stoker, having written two novels with characters and settings drawn from his native Ireland, was working on a new story, set in Styria in Austria, with a central character called Count Wampyr.

Stoker had a week on his own to explore before being joined by his wife and baby son. Mrs Veazey liked to clean his room each morning, so he’d stroll from the genteel heights of Royal Crescent down into the town. On the way, he took in the kind of views that had been exciting writers, artists and Romantic-minded visitors for the past century.

The favoured Gothic literature of the period was set in foreign lands full of eerie castles, convents and caves. Whitby’s windswept headland, the dramatic abbey ruins, a church surrounded by swooping bats, and a long association with jet – a semi-precious stone used in mourning jewellery – gave a homegrown taste of such thrilling horrors.

Today, every summer season there is a thrilling and popular performance of the story of Dracula at the abbey.

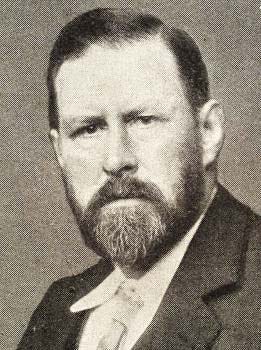

Bram Stoker photographed in about 1906

ABBEY AND CHURCH

High above Whitby, and dominating the whole town, stands Whitby Abbey, the ruin of a once-great Benedictine monastery, founded in the 11th century. The medieval abbey stands on the site of a much earlier monastery, founded in 657 by an Anglian princess, Hild, who became its first abbess. In Dracula, Stoker has Mina Murray – whose experiences form the thread of the novel – record in her diary:

Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey, which was sacked by the Danes … It is a most noble ruin, of immense size, and full of beautiful and romantic bits; there is a legend that a white lady is seen in one of the windows.

Below the abbey stands the ancient parish church of St Mary, perched on East Cliff, which is reached by a climb of 199 steps. Stoker would have seen how time and the weather had gnawed at the graves, some of them teetering precariously on the eroding cliff edge. Some headstones stood over empty graves, marking seafaring occupants whose bodies had been lost on distant voyages. He noted down inscriptions and names for later use, including ‘Swales’, the name he used for Dracula’s first victim in Whitby.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT WHITBY ABBEY’S HISTORY

Graves in St Mary’s churchyard, Whitby, with the abbey ruins in the background

AN ENCOUNTER WITH DRACULA

On 8 August 1890, Stoker walked down to what was known as the Coffee House End of the Quay and entered the public library. It was there that he found a book published in 1820, recording the experiences of a British consul in Bucharest, William Wilkinson, in the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (now in Romania). Wilkinson’s history mentioned a 15th-century prince called Vlad Tepes who was said to have impaled his enemies on wooden stakes. He was known as Dracula – the ‘son of the dragon’. The author had added in a footnote:

Dracula in the Wallachian language means Devil. The Wallachians at that time … used to give this as a surname to any person who rendered himself conspicuous either by courage, cruel actions, or cunning.

Stoker made a note of this name, along with the date.

Anonymous 16th-century painting of Vlad Tepes, or Vlad the Impaler, Prince of Walachia 1456–62

THE BIRTH OF A LEGEND

While staying in Whitby, Stoker would have heard of the shipwreck five years earlier of a Russian vessel called the Dmitry, from Narva. This ran aground on Tate Hill Sands below East Cliff, carrying a cargo of silver sand. With a slightly rearranged name, this became the Demeter from Varna that carries Dracula to Whitby with a cargo of silver sand and boxes of earth.

So, although Stoker was to spend six more years on his novel before it was published, researching the landscapes and customs of Transylvania, the name of his villain and some of the novel’s most dramatic scenes were inspired by his holiday in Whitby. The innocent tourists, the picturesque harbour, the abbey ruins, the windswept churchyard and the salty tales he heard from Whitby seafarers all became ingredients in the novel.

In 1897 Dracula was published. It had an unpromising start as a play called The Undead, in which Stoker hoped Henry Irving would take the lead role. But after a test performance, Irving said he never wanted to see it again. For the character of Dracula, Stoker retained Irving’s aristocratic bearing and histrionic acting style, but he redrafted the play as a novel told in the form of letters, diaries, newspaper cuttings and entries in the ship’s log of the Demeter.

The log charts the gradual disappearance of the entire crew during the journey to Whitby, until only the captain is left, tied to the wheel, as the ship runs aground below East Cliff on 8 August – the date that marked Stoker’s discovery of the name ‘Dracula’ in Whitby library. A ‘large dog’ bounds from the wreck and runs up the 199 steps to the church, and from this moment, things begin to go horribly wrong. Dracula has arrived.

HISTORY

OPINION

BRAM STOKER CLAIMED THAT PARTS OF DRACULA WERE REAL. HERE'S WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT THE STORY BEHIND THE NOVEL

Abraham Stoker (1845 - 1912) the Irish writer who

wrote the classic horror story 'Dracula' in 1897.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

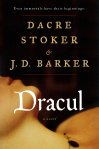

BY DACRE STOKER AND J.D. BARKER

UPDATED: OCTOBER 3, 2018

“There are mysteries that man can only guess at which age by age may only solve in part.” — Bram Stoker

In the summer of 1890, a 45-year-old Bram Stoker entered the Subscription Library in Whitby, England, and requested a specific title — The Accounts of Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia by William Wilkinson. This wasn’t a title found readily on the shelves or typically made available to the general public. The library didn’t even make it known they possessed the rare book. Access was only granted to those who asked for it. Patrons handled the title only under the watchful eye of the librarian, and it was returned to its resting place the moment business concluded. Upon receipt of the book, Stoker didn’t read it cover to cover or browse the text — he opened the pages to a specific section, made notes in his journal, and returned the tome to the librarian.

He stopped next at the Whitby Museum, where he reviewed a series of maps and pieced together a route beginning in the heart of London and ending upon a mountaintop deep within the wilds of Romania — a latitude and longitude previously noted in his journal and confirmed again this very day.

From the museum, Bram then made his way to Whitby Harbor where he spoke to several members of the Royal Coast Guard. They provided details of a sailing vessel, the Dmitri, that ran aground a few years earlier on the beach inside the protective harbor with only a handful of the remaining crew alive. The ship, which originated in Varna, an eastern European port, was carrying a mysterious cargo — crates of earth. While investigating the damaged ship, rescue workers reported seeing a large black dog, consistent with a Yorkshire myth of a beast known as Barghest, escape from the hull of the ship and run up the 199 steps from Tate Sands beach into the graveyard of St. Mary’s Church.

Stoker looked up at the church, at Whitby Abbey looming beside it on the cliff. In his mind’s eye, he pictured the dark chamber at the top of the central tower.

Opening his journal, he turned to the information he’d written down back at the library —

Four months earlier, at a dinner at the Beefsteak Club of the Lyceum Theater in London, Bram Stoker’s friend Arminius Vambery told him of the book, told him what to look for. Told him to visit the library in Whitby. The final piece of a decades-old puzzle, a story, slowly taking shape. On another page of his notes, the name Count Wampyr had recently been crossed out, replaced with Count Dracula and to Bram, it all made sense now.

For fans of the novel Dracula, the information above takes on a familiar note. We all know the name. There’s the graveyard, the Abbey, the dog, and of course, the ship — but it was called The Demeter, right? Not Dmitri… In the book, yes, but in real life it was Dmitri. And there was a “real life.” Bram had found a blurry place between fact and fiction and that surely put a smile on the Irishman’s face.

When Bram Stoker wrote his iconic novel, the original preface, which was published in Makt Myrkanna, the Icelandic version of the story, included this passage: I am quite convinced that there is no doubt whatever that the events here described really took place, however unbelievable and incomprehensible they might appear at first sight. And I am further convinced that they must always remain to some extent incomprehensible.

He went on to claim that many of the characters in his novel were real people: All the people who have willingly — or unwillingly — played a part in this remarkable story are known generally and well respected. Both Jonathan Harker and his wife (who is a woman of character) and Dr. Seward are my friends and have been so for many years, and I have never doubted that they were telling the truth…

Bram Stoker did not intend for Dracula to serve as fiction, but as a warning of a very real evil, a childhood nightmare all too real.

Worried of the impact of presenting such a story as true, his editor, Otto Kyllman, of Archibald Constable & Company, returned the manuscript with a single word of his own: No.

He went on to explain that London was still recovering from a spate of horrible murders in Whitechapel — and with the killer still on the loose, they couldn’t publish such a story without running the risk of generating mass panic. Changes would need to be made. Factual elements would need to come out, and it would be published as fiction or not at all.

When the novel was finally released on May 26, 1897, the first 101 pages had been cut, numerous alterations had been made to the text, and the epilogue had been shortened, changing Dracula’s ultimate fate as well as that of his castle. Tens of thousands of words had vanished. Bram’s message, once concise and clear, had blurred between the remaining lines.

In the 1980s, the original Dracula manuscript was discovered in a barn in rural northwestern Pennsylvania. Nobody knows how it made its way across the Atlantic. That manuscript, now owned by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen, begins on page 102. Jonathan Harker’s journey on a train, once thought to be the beginning of the story, was actually in the thick of it.

This raises a question: what was on the first 101 pages? What was considered too real, too frightening, for publication?

Bram Stoker left breadcrumbs; you need only know where to look. Some of those clues were discovered in a recently translated first edition of Dracula from Iceland titled Makt Myrkranna, or Power of Darkness. Within that first edition, Bram left not only his original preface intact, but parts of his original story — outside the reach of his U.K. publisher. More can be found within the short story Dracula’s Guest, now known to have been excised from the original text. Then there were his notes, his journals, other first editions worldwide. Unable to tell his story as a whole, he spread it out where, much like his famous vampire, it never died, only slept, waited.

Penguin Random House

J.D. Barker is the international bestselling author of Forsaken, The Fourth Monkey, and The Fifth to Die. Dacre Stoker is the great-grandnephew of Bram Stoker and the international bestselling co-author of Dracula: The Undead. He manages the Bram Stoker Estate. Together, they are the authors of the novel Dracul, available now, the research for which informed this piece.

The original version of this article mistakenly described the Whitby Abbey tower as destroyed at the time of Bram Stoker’s visit in 1890. The tower was not destroyed until 1914.

---30---