Dyson’s principle of maximum diversity says that without hardship and suffering, life would be too dull

By John Horgan on May 8, 2018

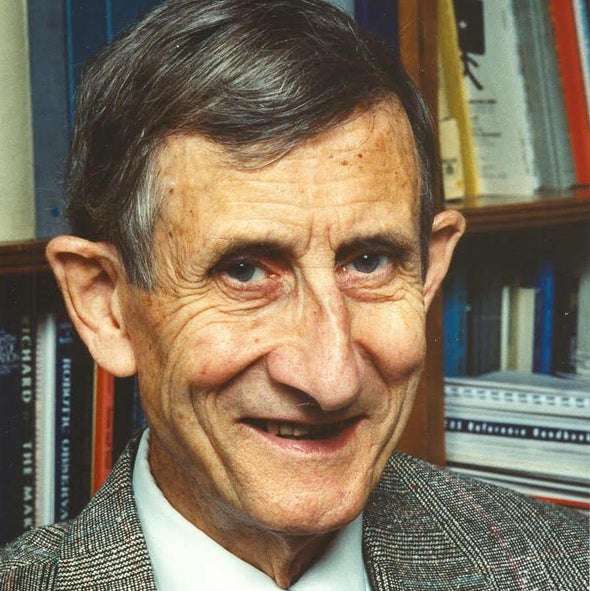

Dyson's principle of maximum diversity decrees that "when things are dull, something turns up to challenge us and to stop us from settling into a rut. Examples of things which made life difficult are all around us: comet impacts, ice ages, weapons, plagues, nuclear fission, computers, sex, sin and death." Credit: Randall Hagadorn, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ US

Freeman Dyson, at the age of 94, is still disturbing the universe. He has a new book out, Maker of Patterns, a collection of annotated letters that tells his life story through the 1970s. He continues writing splendid essays for The New York Review of Books. His latest, in the May 10 issue, ends with the Dysonian sentence, “Freedom is the divine spark that causes human children to rebel against grand unified theories imposed by their parents.”

Hoping to do a Q&A with him, I sent him a dozen questions. I asked, for example, about his assertions that the environmental movement has been “hijacked by a bunch of climate fanatics” and that “paranormal phenomena are real.” (See my 2011 post on Dyson’s “bunkrapt” ideas.) He ignored all the questions except for one about the Singularity. Here is our exchange:

Horgan: You have speculated about the long-term evolution of intelligence since the 1970s. What do you think about the predictions of Ray Kurzweil and others that we are on the verge of a radical transformation of intelligence, or “Singularity”?

Freeman Dyson, at the age of 94, is still disturbing the universe. He has a new book out, Maker of Patterns, a collection of annotated letters that tells his life story through the 1970s. He continues writing splendid essays for The New York Review of Books. His latest, in the May 10 issue, ends with the Dysonian sentence, “Freedom is the divine spark that causes human children to rebel against grand unified theories imposed by their parents.”

Hoping to do a Q&A with him, I sent him a dozen questions. I asked, for example, about his assertions that the environmental movement has been “hijacked by a bunch of climate fanatics” and that “paranormal phenomena are real.” (See my 2011 post on Dyson’s “bunkrapt” ideas.) He ignored all the questions except for one about the Singularity. Here is our exchange:

Horgan: You have speculated about the long-term evolution of intelligence since the 1970s. What do you think about the predictions of Ray Kurzweil and others that we are on the verge of a radical transformation of intelligence, or “Singularity”?

Dyson: The Kurzweil singularity is total nonsense. For better or for worse, human nature is a tough beast, designed to prevail over technological revolutions and natural disasters. It changed only a little in response to the agricultural and industrial revolutions, not to mention ice-ages. It is absurd to imagine it changing radically in a single century.

That’s not enough for a column, so I thought I’d dust off a profile I wrote after interviewing Dyson in 1993 at the Institute for Advanced Study. In the profile, which ended up in The End of Science, I tried to convey Dyson’s personality, and his vision of humanity’s ultimate purpose and destiny. Here is an edited version:

Freeman Dyson is a slight man, all sinew and veins, with a cutlass of a nose and deep-set, watchful eyes. His demeanor is cool, reserved--until he laughs. Then he snorts through his nose, shoulders heaving, like a 12-year-old schoolboy hearing a dirty joke. It is a subversive laugh, the laugh of a man who envisions space as a haven for “religious fanatics” and “recalcitrant teenagers,” who insists that science at its best is “a rebellion against authority.”

Dyson was once at the forefront of the search for a unified theory of physics. In the early 1950s, he contributed to the construction of the quantum theory of electromagnetism. Other physicists have told me that Dyson deserved a Nobel Prize for his work, or at least more credit. They have also suggested that disappointment, as well as a contrarian streak, nudged Dyson away from particle physics and toward pursuits unworthy of his powers.

When I mentioned this assessment to Dyson, he gave me a tight-lipped smile and responded, as he often did, with an anecdote. Lawrence Bragg, he noted, was “a sort of role model.” After Bragg became the director of the University of Cambridge's legendary Cavendish Laboratory in 1938, he steered it away from nuclear physics, on which its mighty reputation rested, and into new territory.

“Everybody thought Bragg was destroying the Cavendish by getting out of the mainstream,” Dyson said. “But of course it was a wonderful decision, because he brought in molecular biology and radio astronomy. Those are the two things which made Cambridge famous over the next 30 years or so.”

Dyson, too, has spent much of his career swerving away from the mainstream. He veered from mathematics, his focus in college, into quantum theory, and then into solid-state physics, nuclear engineering, arms control, climate studies and speculation about humanity’s destiny.

He wrote his 1979 paper “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe,” in response to Steven Weinberg’s infamous remark that “the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” No universe with intelligence is pointless, Dyson retorted. He argued that in an open, eternally expanding universe, our descendants could resist heat death and endure virtually forever through shrewd conservation of energy.

Dyson did not think biological intelligence would soon yield to artificial intelligence. In his 1988 book Infinite in All Directions, he conjectured that genetic engineers might someday “grow” spacecraft “about as big as a chicken and about as smart,” which could flit on sunlight-powered wings through the solar system and beyond, acting as our scouts. (Dyson called them “astrochickens.”) Civilizations concerned about dwindling energy supplies could capture the radiation of stars by constructing energy-absorbing shells--sometimes called Dyson spheres--around them.

Eventually, Dyson predicted, intelligence might spread through the entire universe, transforming it into one great mind. He asked, “What will mind choose to do when it informs and controls the universe?” The question, for Dyson, has theological significance. “I do not make any clear distinction between mind and God,” he wrote. “God is what mind becomes when it has passed beyond the scale of our comprehension. God may be considered to be either a world-soul or a collection of world souls. We are the chief inlets of God on this planet at the present stage in his development. We may later grow with him as he grows, or we may be left behind.”

Dyson insisted that “no matter how far we go into the future, there will always be new things happening, new information coming in, new worlds to explore, a constantly expanding domain of life, consciousness and memory.” The quest for knowledge would be--must be—“infinite in all directions.” In other words, even a God-like intelligence cannot know everything.

Dyson admitted to me that his vision of the future reflected wishful thinking. When I asked if science is infinite, he replied, “I hope so! It's the kind of world I’d like to live in.” If minds make the universe meaningful, they must have something to think about. Science must, therefore, be eternal. Contrary to what Weinberg and other physicists have suggested, there can be no “final theory” that answers all our questions.

“The only way to think about this is historical,” Dyson explained. Two thousand years ago some “very bright people” invented something that, while not science in the modern sense, was obviously its precursor. “If you go into the future, what we call science won't be the same thing anymore, but that doesn't mean there won't be interesting questions.”

Dyson hoped Godel’s incompleteness theorem might apply to physics as well as to mathematics. “Since we know the laws of physics are mathematical, and we know that mathematics is an inconsistent system, it’s sort of plausible that physics will also be inconsistent”--and therefore open-ended. “So I think these people who predict the end of physics may be right in the long run. Physics may become obsolete. But I would guess myself that physics might be considered something like Greek science: an interesting beginning but it didn't really get to the main point. So the end of physics may be the beginning of something else.”

In Infinite In All Directions Dyson addressed, obliquely, the only theological issue that really matters, the problem of evil. If we were created by a loving, all-powerful God, why is life so painful and unfair? The answer, Dyson suggested, might have something to do with “the principle of maximum diversity.” This principle, he explained, “operates at both the physical and the mental level. It says that the laws of nature and the initial conditions are such as to make the universe as interesting as possible. As a result, life is possible but not too easy. Always when things are dull, something turns up to challenge us and to stop us from settling into a rut. Examples of things which made life difficult are all around us: comet impacts, ice ages, weapons, plagues, nuclear fission, computers, sex, sin and death. Not all challenges can be overcome, and so we have tragedy. Maximum diversity often leads to maximum stress. In the end we survive, but only by the skin of our teeth.”

When I asked Dyson about the principle of maximum diversity, he downplayed it. “I never think of this as a deep philosophical belief,” he said. “It's simply, to me, just a poetic fancy.” Perhaps Dyson was being modest, but to my mind, the principle of maximum diversity has profound implications. It suggests that, even if the cosmos was designed for us, we will never figure it out, and we will never create a blissful paradise, in which all our problems are solved. Without hardship and suffering--without “challenges,” from the war between the sexes to World War II and the Holocaust--life would be too boring. This is a chilling answer to the problem of evil, but I haven’t found a better one.

Postscript: After I emailed this column to Dyson, he replied: Dear John Horgan, Thank you for sending your summary of my more oracular statements. I find the summary accurate and thoughtful. I have nothing to add or subtract, except for one correction. The “Time Without End” paper is obsolete because it assumed a linearly expanding universe, which the cosmologists believed to be correct in 1979. We now have strong evidence that the universe is accelerating, and this makes a big difference to the future of life and intelligence. I prefer not to speculate further until the observational evidence becomes clearer.

That’s not enough for a column, so I thought I’d dust off a profile I wrote after interviewing Dyson in 1993 at the Institute for Advanced Study. In the profile, which ended up in The End of Science, I tried to convey Dyson’s personality, and his vision of humanity’s ultimate purpose and destiny. Here is an edited version:

Freeman Dyson is a slight man, all sinew and veins, with a cutlass of a nose and deep-set, watchful eyes. His demeanor is cool, reserved--until he laughs. Then he snorts through his nose, shoulders heaving, like a 12-year-old schoolboy hearing a dirty joke. It is a subversive laugh, the laugh of a man who envisions space as a haven for “religious fanatics” and “recalcitrant teenagers,” who insists that science at its best is “a rebellion against authority.”

Dyson was once at the forefront of the search for a unified theory of physics. In the early 1950s, he contributed to the construction of the quantum theory of electromagnetism. Other physicists have told me that Dyson deserved a Nobel Prize for his work, or at least more credit. They have also suggested that disappointment, as well as a contrarian streak, nudged Dyson away from particle physics and toward pursuits unworthy of his powers.

When I mentioned this assessment to Dyson, he gave me a tight-lipped smile and responded, as he often did, with an anecdote. Lawrence Bragg, he noted, was “a sort of role model.” After Bragg became the director of the University of Cambridge's legendary Cavendish Laboratory in 1938, he steered it away from nuclear physics, on which its mighty reputation rested, and into new territory.

“Everybody thought Bragg was destroying the Cavendish by getting out of the mainstream,” Dyson said. “But of course it was a wonderful decision, because he brought in molecular biology and radio astronomy. Those are the two things which made Cambridge famous over the next 30 years or so.”

Dyson, too, has spent much of his career swerving away from the mainstream. He veered from mathematics, his focus in college, into quantum theory, and then into solid-state physics, nuclear engineering, arms control, climate studies and speculation about humanity’s destiny.

He wrote his 1979 paper “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe,” in response to Steven Weinberg’s infamous remark that “the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” No universe with intelligence is pointless, Dyson retorted. He argued that in an open, eternally expanding universe, our descendants could resist heat death and endure virtually forever through shrewd conservation of energy.

Dyson did not think biological intelligence would soon yield to artificial intelligence. In his 1988 book Infinite in All Directions, he conjectured that genetic engineers might someday “grow” spacecraft “about as big as a chicken and about as smart,” which could flit on sunlight-powered wings through the solar system and beyond, acting as our scouts. (Dyson called them “astrochickens.”) Civilizations concerned about dwindling energy supplies could capture the radiation of stars by constructing energy-absorbing shells--sometimes called Dyson spheres--around them.

Eventually, Dyson predicted, intelligence might spread through the entire universe, transforming it into one great mind. He asked, “What will mind choose to do when it informs and controls the universe?” The question, for Dyson, has theological significance. “I do not make any clear distinction between mind and God,” he wrote. “God is what mind becomes when it has passed beyond the scale of our comprehension. God may be considered to be either a world-soul or a collection of world souls. We are the chief inlets of God on this planet at the present stage in his development. We may later grow with him as he grows, or we may be left behind.”

Dyson insisted that “no matter how far we go into the future, there will always be new things happening, new information coming in, new worlds to explore, a constantly expanding domain of life, consciousness and memory.” The quest for knowledge would be--must be—“infinite in all directions.” In other words, even a God-like intelligence cannot know everything.

Dyson admitted to me that his vision of the future reflected wishful thinking. When I asked if science is infinite, he replied, “I hope so! It's the kind of world I’d like to live in.” If minds make the universe meaningful, they must have something to think about. Science must, therefore, be eternal. Contrary to what Weinberg and other physicists have suggested, there can be no “final theory” that answers all our questions.

“The only way to think about this is historical,” Dyson explained. Two thousand years ago some “very bright people” invented something that, while not science in the modern sense, was obviously its precursor. “If you go into the future, what we call science won't be the same thing anymore, but that doesn't mean there won't be interesting questions.”

Dyson hoped Godel’s incompleteness theorem might apply to physics as well as to mathematics. “Since we know the laws of physics are mathematical, and we know that mathematics is an inconsistent system, it’s sort of plausible that physics will also be inconsistent”--and therefore open-ended. “So I think these people who predict the end of physics may be right in the long run. Physics may become obsolete. But I would guess myself that physics might be considered something like Greek science: an interesting beginning but it didn't really get to the main point. So the end of physics may be the beginning of something else.”

In Infinite In All Directions Dyson addressed, obliquely, the only theological issue that really matters, the problem of evil. If we were created by a loving, all-powerful God, why is life so painful and unfair? The answer, Dyson suggested, might have something to do with “the principle of maximum diversity.” This principle, he explained, “operates at both the physical and the mental level. It says that the laws of nature and the initial conditions are such as to make the universe as interesting as possible. As a result, life is possible but not too easy. Always when things are dull, something turns up to challenge us and to stop us from settling into a rut. Examples of things which made life difficult are all around us: comet impacts, ice ages, weapons, plagues, nuclear fission, computers, sex, sin and death. Not all challenges can be overcome, and so we have tragedy. Maximum diversity often leads to maximum stress. In the end we survive, but only by the skin of our teeth.”

When I asked Dyson about the principle of maximum diversity, he downplayed it. “I never think of this as a deep philosophical belief,” he said. “It's simply, to me, just a poetic fancy.” Perhaps Dyson was being modest, but to my mind, the principle of maximum diversity has profound implications. It suggests that, even if the cosmos was designed for us, we will never figure it out, and we will never create a blissful paradise, in which all our problems are solved. Without hardship and suffering--without “challenges,” from the war between the sexes to World War II and the Holocaust--life would be too boring. This is a chilling answer to the problem of evil, but I haven’t found a better one.

Postscript: After I emailed this column to Dyson, he replied: Dear John Horgan, Thank you for sending your summary of my more oracular statements. I find the summary accurate and thoughtful. I have nothing to add or subtract, except for one correction. The “Time Without End” paper is obsolete because it assumed a linearly expanding universe, which the cosmologists believed to be correct in 1979. We now have strong evidence that the universe is accelerating, and this makes a big difference to the future of life and intelligence. I prefer not to speculate further until the observational evidence becomes clearer.

Yours sincerely, Freeman Dyson.

Freeman Dyson, global warming, ESP and the fun of being "bunkrapt"

By John Horgan on January 7, 2011

Should a scientist who believes in extrasensory perception—the ability to read minds, intuit the future and so on—be taken seriously? This question comes to mind when I ponder the iconoclastic physicist Freeman Dyson, whom the journalist Kenneth Brower recently profiled in The Atlantic's December issue.

"The Danger of Cosmic Genius" explores Dyson’s denial that global warming will wreak havoc on Earth unless we drastically curtail carbon emissions. Dyson questions the computer models on which these scary scenarios are based, and he suggests that the upside of global warming—including faster plant growth and longer growing seasons in certain regions—may outweigh the downside.

This article resembles Nicholas Dawidoff's 2009 profile of Dyson in The New York Times Magazine—with a crucial difference. Whereas Dawidoff teased us with the possibility that Dyson could be right about global warming, Brower declares right off the bat that Dyson is "dead wrong, wrong on the facts, wrong on the science." Brower's goal is to explain how "someone as smart as Freeman Dyson could be so dumb."

Brower has known Dyson for decades. Brower's 1978 book The Starship and the Canoe was an affectionate study of Dyson and his equally quirky son George, a kayak-designer who in the 1970s lived in a tree in the Pacific Northwest. In his Atlantic article, Brower recounts Dyson's brilliant contributions to particle physics (he helped formulate quantum electrodynamics), nuclear engineering (he designed a method of space transport based on repeated nuclear explosions) and other fields.

Brower weighs several explanations for Dyson's stance on global warming: Brower rejects one obvious possibility, that Dyson, at 87, has "gone out of his beautiful mind"; by all accounts, Dyson's intellect is still formidable (and I found it to be so three years ago when I attended a three-day conference with Dyson in Lisbon). Brower gives more weight to the notion that Dyson—one of whose books is titled The Scientist as Rebel (New York Review Books, 2006)—has always been a provocateur who loves tweaking the status quo. I emphasized this contrarian aspect of Dyson's personality in my 1993 profile of him for Scientific American, titled "Perpendicular to the Mainstream".

Brower's favorite theory is that Dyson possesses a kind of religious faith in the power of science and technology to help us overcome all problems. We can bioengineer ourselves and other species, Dyson asserts, to help us adapt to a warmer world; if Earth becomes uninhabitable, we can colonize other planets, perhaps in other solar systems. "What the secular faith of Dysonism offers is, first, a hypertrophied version of the technological fix," Brower wrote, "and, second, the fantasy that should the fix fail we have someplace else to go."

This analysis makes sense to me. Dyson's worldview seems both oddly retro, in a Jules Verne-ish or even Jetsons-esque way, and hyper-futuristic, so much so that humanity's current problems—notably global warming—fade into insignificance. His remarkable 1979 paper, "Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe," calculates how intelligent beings, perhaps in the form of clouds of charged particles, can ward off heat death—the polar opposite of global warming!—even after all the stars in the cosmos have dimmed.

Much more damaging to Dyson's credibility, however, is his belief in extrasensory perception, sometimes called "psi". Dyson disclosed this belief in his essay "One in a Million" in the March 25, 2004, New York Review of Books, which discussed a book about ESP. His family, Dyson revealed, included two "fervent believers in paranormal phenomena," a grandmother who was a "notorious and successful faith healer" and a cousin who edited the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research.

Dyson proposed that "paranormal phenomena are real but lie outside the limits of science." No one has produced empirical proof of psi, he conjectured, because it tends to occur under conditions of "strong emotion and stress," which are "inherently incompatible with controlled scientific procedures." This explanation reminds me of the physicist Richard Feynman's quip that string theorists don't make predictions; they make excuses.

Dyson even offered an explanation for what the parapsychologist Joseph Rhine called the "decline effect," which I discussed in a previous post. "In a typical card-guessing experiment," Dyson wrote, "the participants may begin the session in a high state of excitement and record a few high scores, but as the hours pass, and boredom replaces excitement, the scores decline." When I ran into Dyson three years ago in Lisbon, he cheerfully affirmed his belief in psi and reiterated his explanations for why it hasn't been empirically demonstrated.

I disagree with Dyson that global warming is no big deal—I urge doubters to read Storms of My Grandchildren (Bloomsbury, 2009) by the climatologist James Hansen—and that ESP is real. Yes, some researchers still claim to have found tentative evidence for psi, as The New York Times reported in a page-one story last week. But if ESP existed, surely someone would have provided definitive proof of it by now and claimed James Randi's $1-million prize for "anyone who can show under proper observing conditions evidence of any paranormal, supernatural or occult power or event."

Despite this lack of evidence, lots of people—including scientists—share Dyson's belief in ESP, just as many share his lack of concern about global warming. And let's not forget that many leading scientists—notably Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health—believe in a God who performs miracles, like resurrecting the dead. Eminent physicists also postulate the existence of parallel universes, higher dimensions, strings and other phenomena that I find as incredible as psi.

In his 1984 book, The Limits of Science, the biologist Peter Medawar coined the term "bunkrapt" to describe people infatuated with "bunk," meaning religious beliefs, superstitions and other claims lacking empirical evidence. "It is fun sometimes to be bunkrapt," Medawar wrote. That's a nice way of putting it. The gleeful rebel Dyson, it seems to me, embodies our bunkrapt era, when the delineation between knowledge and pseudo-knowledge is becoming increasingly blurred; genuine authorities are mistaken for hucksters and vice versa; and we all believe whatever damn thing we want to believe.

Photo of Dyson courtesy Wiki Common

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

John Horgan

John Horgan directs the Center for Science Writings at the Stevens Institute of Technology. His books include The End of Science, The End of War and Mind-Body Problems, available for free at mindbodyproblems.com.

Recent Articles

Scientific Rebel Freeman Dyson Dies

Astrology, Tarot Cards and Psychotherapy

Responses to "The Cancer Industry: Hype vs. Reality"

Freeman Dyson, global warming, ESP and the fun of being "bunkrapt"

By John Horgan on January 7, 2011

Should a scientist who believes in extrasensory perception—the ability to read minds, intuit the future and so on—be taken seriously? This question comes to mind when I ponder the iconoclastic physicist Freeman Dyson, whom the journalist Kenneth Brower recently profiled in The Atlantic's December issue.

"The Danger of Cosmic Genius" explores Dyson’s denial that global warming will wreak havoc on Earth unless we drastically curtail carbon emissions. Dyson questions the computer models on which these scary scenarios are based, and he suggests that the upside of global warming—including faster plant growth and longer growing seasons in certain regions—may outweigh the downside.

This article resembles Nicholas Dawidoff's 2009 profile of Dyson in The New York Times Magazine—with a crucial difference. Whereas Dawidoff teased us with the possibility that Dyson could be right about global warming, Brower declares right off the bat that Dyson is "dead wrong, wrong on the facts, wrong on the science." Brower's goal is to explain how "someone as smart as Freeman Dyson could be so dumb."

Brower has known Dyson for decades. Brower's 1978 book The Starship and the Canoe was an affectionate study of Dyson and his equally quirky son George, a kayak-designer who in the 1970s lived in a tree in the Pacific Northwest. In his Atlantic article, Brower recounts Dyson's brilliant contributions to particle physics (he helped formulate quantum electrodynamics), nuclear engineering (he designed a method of space transport based on repeated nuclear explosions) and other fields.

Brower weighs several explanations for Dyson's stance on global warming: Brower rejects one obvious possibility, that Dyson, at 87, has "gone out of his beautiful mind"; by all accounts, Dyson's intellect is still formidable (and I found it to be so three years ago when I attended a three-day conference with Dyson in Lisbon). Brower gives more weight to the notion that Dyson—one of whose books is titled The Scientist as Rebel (New York Review Books, 2006)—has always been a provocateur who loves tweaking the status quo. I emphasized this contrarian aspect of Dyson's personality in my 1993 profile of him for Scientific American, titled "Perpendicular to the Mainstream".

Brower's favorite theory is that Dyson possesses a kind of religious faith in the power of science and technology to help us overcome all problems. We can bioengineer ourselves and other species, Dyson asserts, to help us adapt to a warmer world; if Earth becomes uninhabitable, we can colonize other planets, perhaps in other solar systems. "What the secular faith of Dysonism offers is, first, a hypertrophied version of the technological fix," Brower wrote, "and, second, the fantasy that should the fix fail we have someplace else to go."

This analysis makes sense to me. Dyson's worldview seems both oddly retro, in a Jules Verne-ish or even Jetsons-esque way, and hyper-futuristic, so much so that humanity's current problems—notably global warming—fade into insignificance. His remarkable 1979 paper, "Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe," calculates how intelligent beings, perhaps in the form of clouds of charged particles, can ward off heat death—the polar opposite of global warming!—even after all the stars in the cosmos have dimmed.

Much more damaging to Dyson's credibility, however, is his belief in extrasensory perception, sometimes called "psi". Dyson disclosed this belief in his essay "One in a Million" in the March 25, 2004, New York Review of Books, which discussed a book about ESP. His family, Dyson revealed, included two "fervent believers in paranormal phenomena," a grandmother who was a "notorious and successful faith healer" and a cousin who edited the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research.

Dyson proposed that "paranormal phenomena are real but lie outside the limits of science." No one has produced empirical proof of psi, he conjectured, because it tends to occur under conditions of "strong emotion and stress," which are "inherently incompatible with controlled scientific procedures." This explanation reminds me of the physicist Richard Feynman's quip that string theorists don't make predictions; they make excuses.

Dyson even offered an explanation for what the parapsychologist Joseph Rhine called the "decline effect," which I discussed in a previous post. "In a typical card-guessing experiment," Dyson wrote, "the participants may begin the session in a high state of excitement and record a few high scores, but as the hours pass, and boredom replaces excitement, the scores decline." When I ran into Dyson three years ago in Lisbon, he cheerfully affirmed his belief in psi and reiterated his explanations for why it hasn't been empirically demonstrated.

I disagree with Dyson that global warming is no big deal—I urge doubters to read Storms of My Grandchildren (Bloomsbury, 2009) by the climatologist James Hansen—and that ESP is real. Yes, some researchers still claim to have found tentative evidence for psi, as The New York Times reported in a page-one story last week. But if ESP existed, surely someone would have provided definitive proof of it by now and claimed James Randi's $1-million prize for "anyone who can show under proper observing conditions evidence of any paranormal, supernatural or occult power or event."

Despite this lack of evidence, lots of people—including scientists—share Dyson's belief in ESP, just as many share his lack of concern about global warming. And let's not forget that many leading scientists—notably Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health—believe in a God who performs miracles, like resurrecting the dead. Eminent physicists also postulate the existence of parallel universes, higher dimensions, strings and other phenomena that I find as incredible as psi.

In his 1984 book, The Limits of Science, the biologist Peter Medawar coined the term "bunkrapt" to describe people infatuated with "bunk," meaning religious beliefs, superstitions and other claims lacking empirical evidence. "It is fun sometimes to be bunkrapt," Medawar wrote. That's a nice way of putting it. The gleeful rebel Dyson, it seems to me, embodies our bunkrapt era, when the delineation between knowledge and pseudo-knowledge is becoming increasingly blurred; genuine authorities are mistaken for hucksters and vice versa; and we all believe whatever damn thing we want to believe.

Photo of Dyson courtesy Wiki Common

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

John Horgan

John Horgan directs the Center for Science Writings at the Stevens Institute of Technology. His books include The End of Science, The End of War and Mind-Body Problems, available for free at mindbodyproblems.com.

Recent Articles

Scientific Rebel Freeman Dyson Dies

Astrology, Tarot Cards and Psychotherapy

Responses to "The Cancer Industry: Hype vs. Reality"

Credit:

Credit: