The Scariest Things in the Universe Are Black Holes – Here’s Why

Halloween is a time to be haunted by ghosts, goblins, and ghouls, but nothing in the universe is scarier than a black hole.

Black holes – regions in space where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape – are a hot topic in the news these days. Half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Roger Penrose for his mathematical work showing that black holes are an inescapable consequence of Einstein’s theory of gravity. Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel shared the other half for showing that a massive black hole sits at the center of our galaxy.

Black holes are scary for three reasons. If you fell into a black hole left over when a star died, you would be shredded. Also, the massive black holes seen at the center of all galaxies have insatiable appetites. And black holes are places where the laws of physics are obliterated.

I’ve been studying black holes for over 30 years. In particular, I’ve focused on the supermassive black holes that lurk at the center of galaxies. Most of the time they are inactive, but when they are active and eat stars and gas, the region close to the black hole can outshine the entire galaxy that hosts them. Galaxies where the black holes are active are called quasars. With all we’ve learned about black holes over the past few decades, there are still many mysteries to solve.

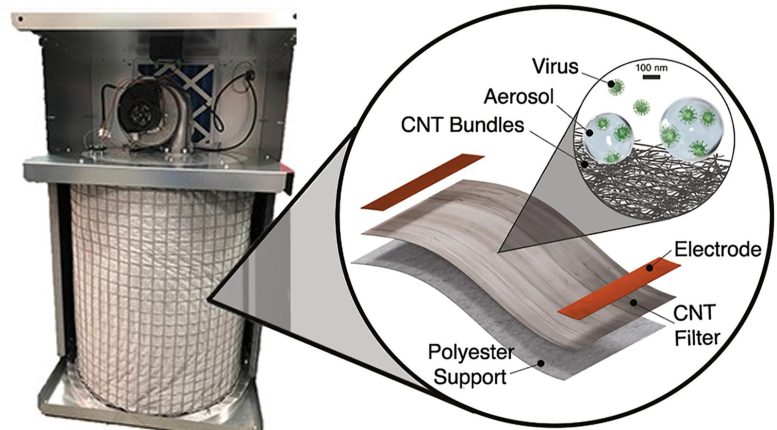

Artist’s impression of a disc of material circling a supermassive black hole. Credit: ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser

Death by black hole

Black holes are expected to form when a massive star dies. After the star’s nuclear fuel is exhausted, its core collapses to the densest state of matter imaginable, a hundred times denser than an atomic nucleus. That’s so dense that protons, neutrons and electrons are no longer discrete particles. Since black holes are dark, they are found when they orbit a normal star. The properties of the normal star allow astronomers to infer the properties of its dark companion, a black hole.

The first black hole to be confirmed was Cygnus X-1, the brightest X-ray source in the Cygnus constellation. Since then, about 50 black holes have been discovered in systems where a normal star orbits a black hole. They are the nearest examples of about 10 million that are expected to be scattered through the Milky Way.

Black holes are tombs of matter; nothing can escape them, not even light. The fate of anyone falling into a black hole would be a painful “spaghettification,” an idea popularized by Stephen Hawking in his book “A Brief History of Time.” In spaghettification, the intense gravity of the black hole would pull you apart, separating your bones, muscles, sinews and even molecules. As the poet Dante described the words over the gates of hell in his poem Divine Comedy: Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

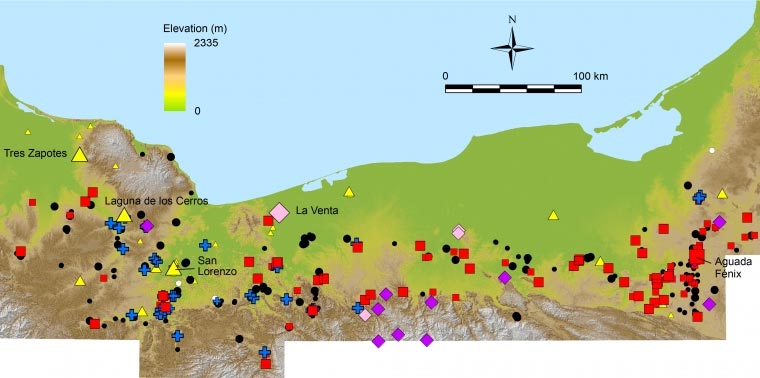

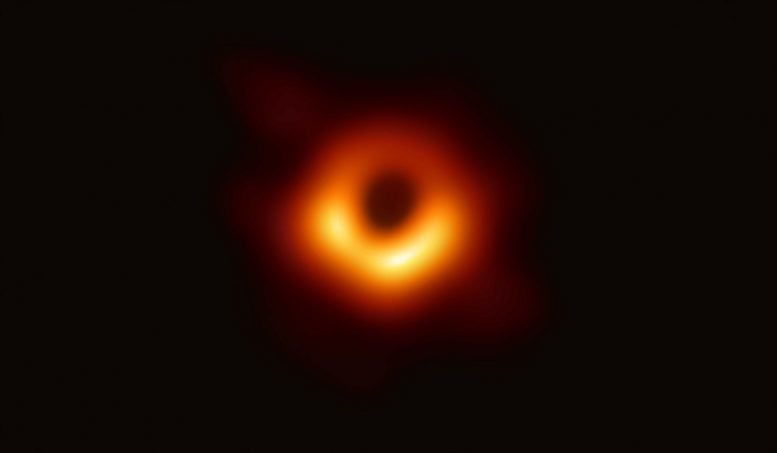

A photograph of a black hole at the center of galaxy M87. The black hole is outlined by emission from hot gas swirling around it under the influence of strong gravity near its event horizon. Credit: EHT

A hungry beast in every galaxy

Over the past 30 years, observations with the Hubble Space Telescope have shown that all galaxies have black holes at their centers. Bigger galaxies have bigger black holes.

Nature knows how to make black holes over a staggering range of masses, from star corpses a few times the mass of the Sun to monsters tens of billions of times more massive. That’s like the difference between an apple and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Just last year, astronomers published the first-ever picture of a black hole and its event horizon, a 7-billion-solar-mass beast at the center of the M87 elliptical galaxy.

It’s over a thousand times bigger than the black hole in our galaxy, whose discoverers snagged this year’s Nobel Prize. These black holes are dark most of the time, but when their gravity pulls in nearby stars and gas, they flare into intense activity and pump out a huge amount of radiation. Massive black holes are dangerous in two ways. If you get too close, the enormous gravity will suck you in. And if they are in their active quasar phase, you’ll be blasted by high-energy radiation.

How bright is a quasar? Imagine hovering over a large city like Los Angeles at night. The roughly 100 million lights from cars, houses and streets in the city correspond to the stars in a galaxy. In this analogy, the black hole in its active state is like a light source 1 inch in diameter in downtown LA that outshines the city by a factor of hundreds or thousands. Quasars are the brightest objects in the universe.

Supermassive black holes are strange

The biggest black hole discovered so far weighs in at 40 billion times the mass of the Sun, or 20 times the size of the solar system. Whereas the outer planets in our solar system orbit once in 250 years, this much more massive object spins once every three months. Its outer edge moves at half the speed of light. Like all black holes, the huge ones are shielded from view by an event horizon. At their centers is a singularity, a point in space where the density is infinite. We can’t understand the interior of a black hole because the laws of physics break down. Time freezes at the event horizon and gravity becomes infinite at the singularity.

The good news about massive black holes is that you could survive falling into one. Although their gravity is stronger, the stretching force is weaker than it would be with a small black hole and it would not kill you. The bad news is that the event horizon marks the edge of the abyss. Nothing can escape from inside the event horizon, so you could not escape or report on your experience.

According to Stephen Hawking, black holes are slowly evaporating. In the far future of the universe, long after all stars have died and galaxies have been wrenched from view by the accelerating cosmic expansion, black holes will be the last surviving objects.

The most massive black holes will take an unimaginable number of years to evaporate, estimated at 10 to the 100th power, or 10 with 100 zeroes after it. The scariest objects in the universe are almost eternal.

Written by Chris Impey, University Distinguished Professor of Astronomy, University of Arizona

Originally published on The Conversation.![]()