Russia’s Pleistocene Park provides a strong example of what can be done to help prevent the release of greenhouse gases as Canada’s permafrost thaws

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ABR7A24A2BPD3PEFA4ITTQYTMY.JPG)

Sergey Zimov, 66, a scientist who works at Russia's Northeast Science Station, tries to take a picture of a camel at the Pleistocene Park outside the town of Chersky, Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, Russia, on Sept. 13.

In Eastern Siberia, above the Arctic Circle, Russian researchers are attempting to bring back landscapes not seen since mammoths roamed the Earth. At Pleistocene Park, they’ve fenced off 16 square kilometres and introduced bison, muskox, horses and other herbivores. They hope the animals’ grazing will transform the landscape into grassland, which will cool the underlying permafrost.

Uninitiated visitors might mistake the Arctic for one of Earth’s last great unspoiled wildernesses. Nikita Zimov, Pleistocene Park’s director, regards it as an ecosystem degraded by hunters who arrived 14,500 years ago. They quickly wiped out mammoths and other large animals, he says, resulting in the disappearance of expansive grasslands they once maintained.

“In the Russian Arctic you don’t really see much wildlife – it’s a sad situation,” he said. “We’ve started to bring animals in, and we are supporting them.”

This Tiny Creature Survived 24,000 Years Frozen in Siberian Permafrost

A father and son’s Ice Age plot to slow Siberian thaw

Established in 1996, Pleistocene Park attracted greater interest during the last decade as scientists began studying “permafrost carbon feedback.” Permafrost contains a motherlode of organic matter that will decompose if unfrozen, releasing carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change expects widespread permafrost thaw this century as temperatures rise. Many researchers fear that could produce a calamitous cycle, in which releases from permafrost beget more warming which begets still more thawing, effectively turbocharging climate change.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/VJW5KNHNQNNDZJJDHBGHCLPKMM.JPG)

An employee of the Pleistocene Park leaves for holidays, outside the town of Chersky, in Yakutia Republic, Russia, Sept. 13, 2021.MAXIM SHEMETOV/REUTERS

Ted Schuur, a professor at Northern Arizona University’s Center for Ecosystem Sciences and Society, said that in well-studied regions like Alaska, there’s evidence thawing permafrost is already releasing greenhouse gases. Although he acknowledged there’s less evidence from other regions. “We should act as a society even in the face of uncertainty,” he said, “as this issue is unlikely to go away.” Canada has declared that it must act decisively to limit permafrost thaw.

But act how, precisely?

There are few cogent, targeted options. At a conference earlier this year organized by the PCF Action Group, a new collaboration among scientists, permafrost engineers, entrepreneurs, participants focused on massive “geoengineering” schemes intended to affect Earth’s entire climate. Many of the ambitious proposals read like science fiction film scripts.

But the approach taken at Pleistocene Park, which has been dubbed “megafaunal ecological engineering,” is among the more mature: Mr. Zimov’s experiment, after all, has been running for a quarter century.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/X45YQWSQAROPHG62HUPBOOR7CI.JPG)

Vadim Meshcheryakov, an employee of the Pleistocene Park, checks greenhouse gas sensors at the Ambolikha station, outside of the town of Chersky, Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, Russia.MAXIM SHEMETOV/REUTERS

Grassland protects permafrost by changing the landscape’s albedo – that is, its ability to reflect sunlight. Grassland’s albedo is far higher than tundra dominated by moss and shrubs, or taiga forest, particularly when it’s covered by snow and ice. Grazing animals also trample snow in winter, reducing its insulating effect and thus chilling the ground underneath.

A 2019 study by the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford suggests this approach works: mean soil temperatures in the park’s grazed areas were 2.2 degrees Celsius cooler than in a control area. (Mr. Zimov co-authored the study.) John Moore, a professor at the University of Lapland in Finland who specializes in climate research and geoengineering, said that finding demonstrates “a pretty significant improvement in the long-term stability of the permafrost.”

Different grazing patterns have been shown to change land albedo elsewhere, he added. Norwegian reindeer herders use their side of the fenced border between Norway and Finland primarily in winter; in summer their side is dominated by white lichens that reflect sunlight. Finland’s much larger reindeer herds graze on the other side of the fence in summertime, eating the lichens and promoting a greener landscape.

But it’s unclear how megafaunal engineering could be scaled up sufficiently to protect large swaths of Arctic permafrost.

Pleistocene Park’s evolution has been painfully slow. Mr. Zimov’s father, Sergey Zimov, began his first grazing experiments in 1988 but the Soviet Union’s collapse interrupted them. In 1996, he resumed the work, establishing Pleistocene Park. It’s now home to roughly 40 Yakutian horses, a dozen bison, three musk ox, 20 reindeer, fewer than 15 moose, 18 sheep, eight yak and 15 cattle – a curious menagerie, but hardly a sprawling new biome.

Of 2,000 hectares in the fenced area, Mr. Zimov estimates that only 100 hectares are halfway through their transition to grassland; the rest of the park is at earlier stages.

“I don’t think there are any places in the park where we’re able to say, ‘We are done here,’” he said. “But I see that many places are in transition. Overall, the productivity is increasing.”

One reason for the painstaking progress was that the Zimov family funded the project’s early development almost entirely. More recently, the project has begun to win sponsors. But the 2019 paper acknowledged that a rigorous experiment would require thousands of animals – an expensive proposition. Introducing three herds of 1,000 animals each would cost an estimated US$114 million.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ZF3QMXKLEJMDTKUZQZWAGFTELA.JPG)

A piece of mammoth's tusk lies in the waters of the Kolyma river at Duvanny Yar southwest of the town of Chersky in Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, Russia, September 12, 2021.MAXIM SHEMETOV/REUTERS

Herds can’t be conjured out of thin air. The muskox and bison largely look after themselves, Mr. Zimov said, but researchers must provide forage for other species during the harsh winters. Mr. Zimov plans further interventions such as introducing predators to encourage “landscapes of fear,” which would change grazing patterns. (Left unmolested, many herbivores don’t move around much in winter, meaning they won’t trample enough snow.) Mr. Zimov has even broached the possibility of reintroducing long-extinct creatures such as mammoths and cave lions, though the 2019 paper acknowledged that neither is “available in the near future.”

Such ongoing and planned intervention highlights the reality that Pleistocene Park is not self-sustaining. It’s not clear it will ever be.

Mr. Zimov himself was uncertain whether the concept could be replicated elsewhere. Like Russia, he said, Canada has large swaths of unpopulated territory, and lots of permafrost. But the geography is different: Much of Canada’s north is rocky and contains less carbon-risk permafrost. More research would be needed, he said, to determine whether it could work here.

“Even though everybody loves the idea of rewilding the Arctic, reversing the changes that humans caused by hunting mammoths and other large fauna to extinction,” Dr. Moore observed, “in practice it’s a little more difficult.”

Indeed, the risks of geoengineering are high.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/VJE2EUJDHBO3HP4QADTC7F37UA.JPG)

(Above) A general view of forest and tundra areas outside the town of Chersky, Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, Russia. (Below) Sergey Zimov, 66, a scientist who works at Russia's Northeast Science Station, checks for permafrost at the Pleistocene Park outside the town of Chersky, Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, Russia. September 13, 2021.MAXIM SHEMETOV/REUTERS

Damon Matthews, a professor of climate science and sustainability at Concordia University, told conference attendees about historical interventions in ecosystems such as an attempt in the late 19th century to protect Hawaii’s sugarcane industry from rat infestation. Since rats were an invasive species with no natural predators on the islands, mongoose were introduced. It was belatedly recognized that rats are nocturnal and mongoose hunt during the day, so the mongoose hunted and destroyed other species such as sea turtles instead.

“The history of biocontrol, from mongooses in Hawaii, to cane toads in Australia, to African land snails, show that attempts to intervene in complex ecological systems have led to worse outcomes,” Dr. Matthews said. “Geoengineering would very likely increase, rather than decrease, net climate damages. What we need to do is get on with decarbonization itself.”

But today’s Arctic, Mr. Zimov contends, is itself the product of large-scale human intervention. The grasslands he’s attempting to restore were “the most productive ecosystems which have ever been on our planet,” he said. “We destroyed it. And I think it’s now a possibility to bring it back.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/EINH5SGJUNMJRLM336TH24DIF4.JPG)

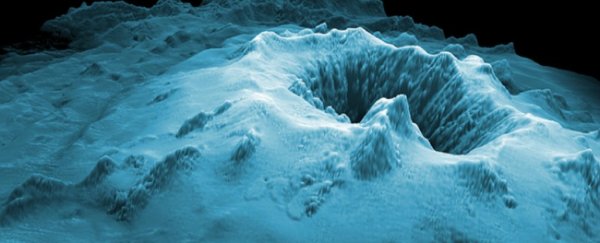

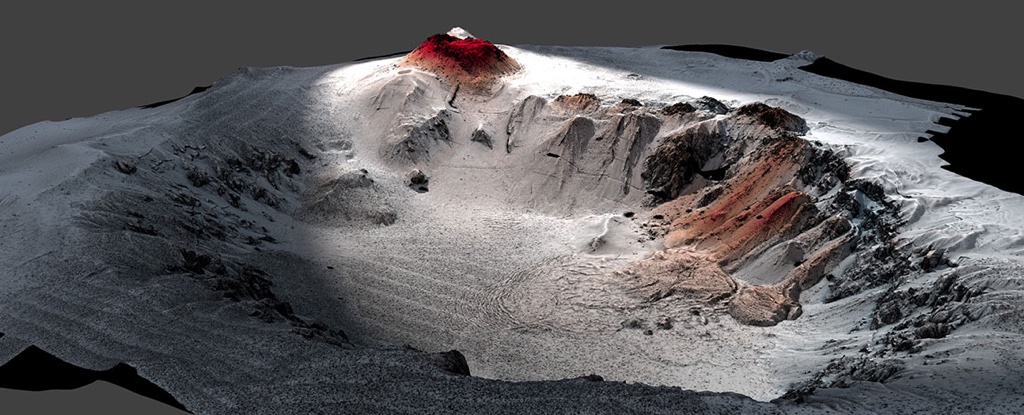

Duvanny Yar gives a side-on view of the permafrost thaw taking place underground where ancient Pleistocene-era flora and fauna have been frozen for millennia

Tom Balmforth and Clare Baldwin

Sat, November 27, 2021

Scientist Sergey Zimov checks for permafrost at the Pleistocene Park outside the town of Chersky, Russia (Reuters)

In one of the planet’s coldest places, 130km south of Russia’s Arctic coast, scientist Sergey Zimov can find no sign of permafrost as global warming permeates Siberia’s soil.

As everything from mammoth bones to ancient vegetation frozen inside it for millennia thaws and decomposes, it now threatens to release vast amounts of greenhouse gases.

Zimov, who has studied permafrost from his scientific base in the diamond-producing Yakutia region for decades, is seeing the effects of climate change in real time.

An abandoned vessel is seen near the Northeast Science Station (Reuters)

Sergey checks materials stored underground in the permafrost (Reuters)

Driving a thin metal pole metres into the Siberian turf, where temperatures are rising at more than three times the world average, with barely any force, the 66-year-old is matter-of-fact.

“This is one of the coldest places on Earth and there is no permafrost,” he says. “Methane has never increased in the atmosphere at the speed it is today... I think this is linked to our permafrost.”

Permafrost covers 65 per cent of Russia’s landmass and about a quarter of the northern landmass. Scientists say that greenhouse gas emissions from its thaw could eventually match or even exceed the European Union’s industrial emissions due to the sheer volume of decaying organic matter.

Meanwhile, permafrost emissions, which are seen as naturally occurring, are not counted against government pledges aimed at curbing emissions or in the spotlight at the UN climate talks. Zimov, with his white beard and cigarette, ignored orders to leave the Arctic when the Soviet Union collapsed and instead found funding to keep the Northeast Science Station near the part-abandoned town of Chersky operating.

Citing data from a US-managed network of global monitoring stations, Zimov says he now believes the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that permafrost has begun to release greenhouse gases.

A house located on land that has been deformed by permafrost thaw (Reuters)

An industrial building that was destroyed when the permafrost thawed under its foundation (Reuters)

Maria Nedostupenko looks out of the window at her home which was damaged by permafrost under its foundation (Reuters)

Despite factories scaling back activity worldwide during the pandemic, which also dramatically slowed global transport, Zimov says the concentration of methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has been growing at a faster rate.

Whole cities sit on permafrost and its thawing could cost Russia 7 trillion roubles (£750m) in damage by 2050 if the rate of warming continues, scientists say.

Built on the assumption that the permafrost would never thaw, many homes, pipelines and roads in Russia’s far north and east are now sinking and increasingly in need of repair.

Ice age animals

Zimov wants to slow the thaw in one area of Yakutia by populating a nature reserve called the Pleistocene Park with large herbivores including bison, horses and camels.

Horses graze on the grounds of the Pleistocene Park (Reuters)

Such animals trample the snow, making it much more compact so the winter cold can get through to the ground, rather than it acting as a thick insulating blanket.

Zimov and his son Nikita began introducing animals into the fenced park in 1996 and have so far relocated around 200 of different species, which they say are making the permafrost colder compared with other areas.

Bison were trucked and shipped this summer from Denmark, along the northern sea route, past polar bears and walruses and through weeks-long storms, before their ship finally turned into the mouth of the Kolyma River towards their new home some 6,000 kilometres to the east.

The Zimovs’ surreal plan for geo-engineering a cooler future has extended to offering a home for mammoths, which other scientists hope to resurrect from extinction with genetic techniques, in order to mimic the region’s ecosystem during the last ice age that ended 11,700 years ago.

Nikolay Basharin, a scientist, holds a bull's skull in an underground permafrost laboratory (Reuters)

Trees lean precariously at Duvanny Yar (Reuters)

A paper published in Nature’s Scientific Reports last year, where both Zimovs were listed as authors, showed that the animals in Pleistocene Park had reduced the average snow depth by half, and the average annual soil temperature by 1.9C, with an even bigger drop in winter and spring.

More work is needed to determine if such “unconventional” methods might be an effective climate change mitigation strategy but the density of animals in Pleistocene Park – 114 per square kilometre – should be feasible on a pan-Arctic scale, it said.

And global-scale models suggest introducing big herbivores onto the tundra could stop 37 per cent of Arctic permafrost from thawing, the paper said.

Permathaw?

Nikita was walking in the shallows of the river Kolyma at Duvanny Yar in September when he fished out a mammoth tusk and tooth. Such finds have been common for years in Yakutia and particularly by rivers where the water erodes the permafrost.

Three hours by boat from Chersky, the river bank provides a cross-section of the thaw, with a thick sheet of exposed ice melting and dripping below layers of dense black earth containing small grass roots.

Nikita Zimov, the director of the Pleistocene park, holds a piece of a mammoth’s tusk (Reuters)

A bone is seen on the bank of the Kolyma river (Reuters)

“If you take the weight of all these roots and decaying organics in the permafrost from Yakutia alone, you’d find the weight was more than the land-based biomass of the planet,” Nikita says.

Scientists say that on average, the world has warmed one degree in the last century, while in Yakutia over the last 50 years, the temperature has risen three degrees.

The older Zimov says he has seen for himself how winters have grown shorter and milder, while Alexander Fedorov, deputy director of the Melnikov Permafrost Institute in Yakutsk, says he no longer has to wear fur clothing during the coldest months.

But addressing permafrost emissions, like fire and other so-called natural emissions, presents a challenge because they are not fully accounted for in climate models or international agreements, scientists say.

“The difficulty is the quantity,” says Chris Burn, a professor at Carleton University in Canada and president of the International Permafrost Association. “One or two per cent of permafrost carbon is equivalent to total global emissions for a year.”

Scientists estimate that permafrost in the northern hemisphere contains about 1.5 trillion tonnes of carbon – about twice as much as is currently in the atmosphere, or about three times as much as in all of the trees and plants on Earth.

Nikita says there is no single solution to global warming. “We’re working to prove that these ecosystems will help in the fight, but, of course, our efforts alone are not enough.”

Photography by Maxim Shemetov, Reuters

Read More