From driving medical facilities out of business to charging predatory interest rates on patient billing schemes, F. Douglas Stephenson outlines how private equity is stealthily destroying Americans’ healthcare.

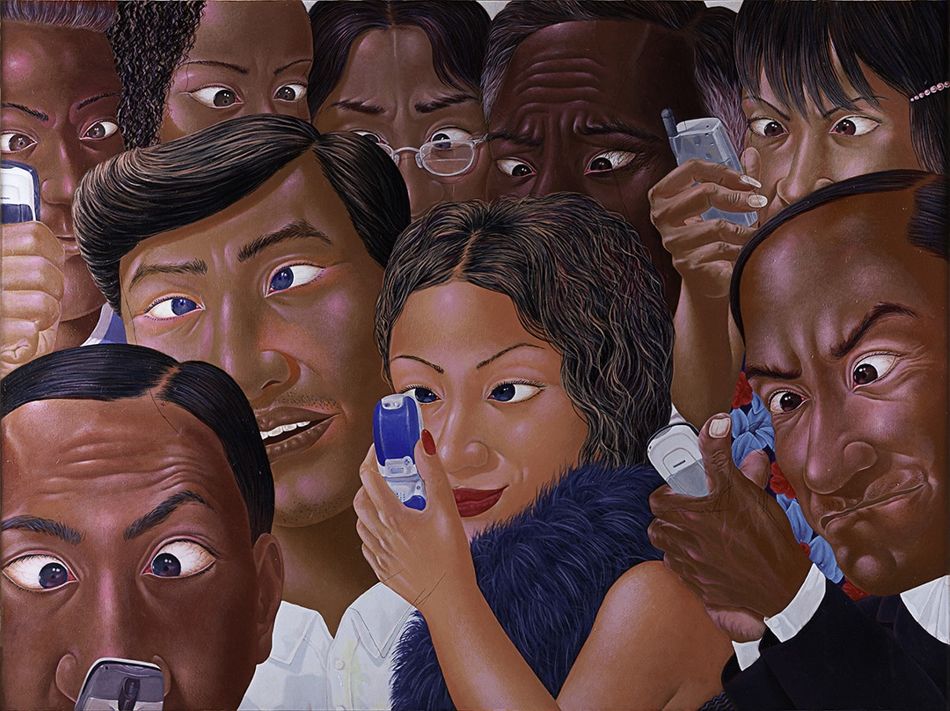

Healthcare, Not Wealthcare! rally in Philadelphia, June 22, 2017.

By F. Douglas Stephenson

Common Dreams

December 1, 2022

The essence of this toxic parasitism is not only to drain the host’s nourishment, but also to dull the host’s brain so that it often does not even recognize that the parasite is there. This is the illusion that health care services in the United States suffer under today.

Parasitic private equity is consuming U.S. health care from the inside out, weakening its structure and strength and enriching investors at the expense of patient care and patients.

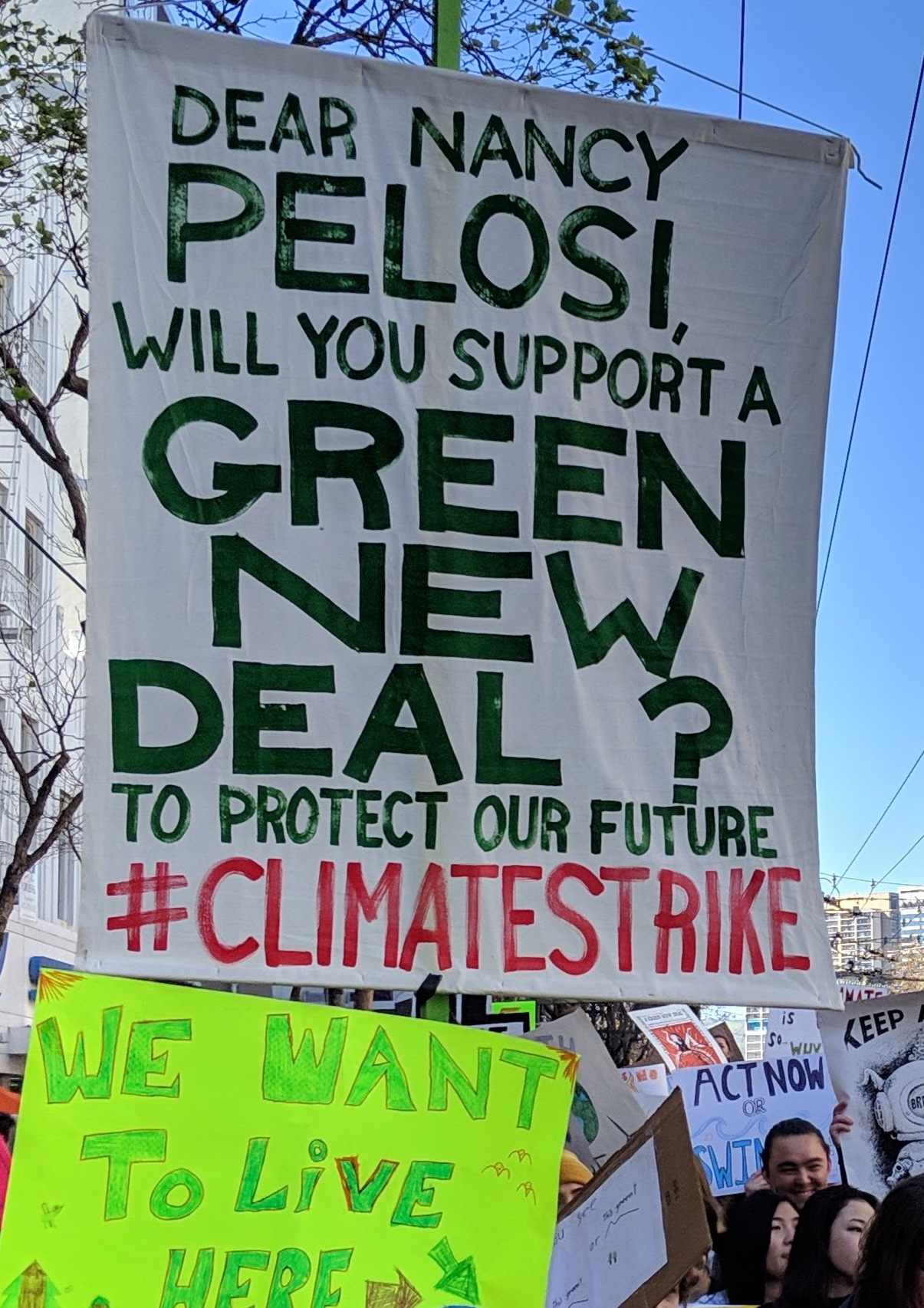

Incremental health reforms have failed. It’s time to move past political barriers to achieve consensus on real reform, says J.E. McDonough, professor of practice at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

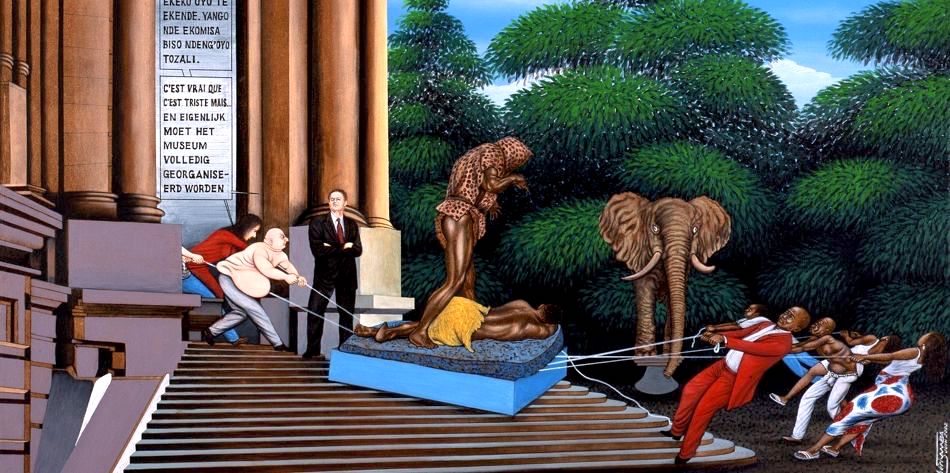

Private equity firms are financial termites devouring the woodwork and foundations of the U.S. health care system, as Laura Katz Olson documents in her new book, Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms US Health Care:

“PE firms are gobbling up physician and dental practices; homecare and hospital agencies; mental health, substance abuse, eating disorder, and autism services; urgent care facilities; and emergency medical transportation.”

Private equity has become a growing and diversified part of the American health care economy. Demonstrated results of private equity ownership include higher patient mortality, higher patient costs, fewer jobs, poorer quality and closed facilities.

What is Private Equity?

But that doesn’t capture the scale of the model. There are also private equity-like businesses that scour the landscape for companies, buy them, and then use extractive techniques such as price gouging or legalized forms of complex fraud to generate cash by moving debt and assets like real estate among shell companies. PE funds also lend money and act as brokers, and are morphing into investment bank-like institutions. Some of them are public companies.

[Related: When Wall Street Came to My Mobile Home Park]

While the movement is couched in the language of business, using terms like strategy, business models, returns on equity, innovation, and so forth, and proponents refer to it as an industry, private equity is not business.

On a deeper level, private equity is the ultimate example of the collapse of the enlightenment concept of what ownership means. Ownership used to mean dominion over a resource, and responsibility for caretaking that resource.

[Related: The Consequences of Moving from Industrial to Financial Capitalism]

PE is a political movement with the goal of extending deep managerial controls from a small group of financiers over the producers in the economy. Private equity transforms corporations from institutions that house people and capital for the purpose of production into extractive institutions designed solely to shift cash to owners and leave the rest behind as trash.

Like much of our political economy, the ideas behind it were developed in the 1970s and the actual implementation was operationalized during the Reagan era.

Journalist Matt Stoller describes the essential business plan of private equity:

“Financial engineers… raise large amounts of money and borrow even more to buy firms and loot them. These kinds of private equity barons aren’t healthcare specialists who help finance useful health products and services, they do cookie-cutter deals targeting firms/practices/hospitals they believe have market power to raise prices, who can lay off workers or sell assets, and/or have some sort of legal loophole advantage.

Often, they will destroy the underlying business. The giants of the industry, from Blackstone to Apollo to Bain, are the children of 1980s junk bond king and fraudster Michael Milken. They are essentially super-sized mobsters.”

The classic description of this looting-for-profit practice process is presented by economists George Akerloff and Paul Romer:

“Firms have an incentive to go broke for profit at society’s expense (to loot) instead of to go for broke (to gamble on success). Bankruptcy for profit will occur if poor accounting, lax regulation, or low penalties for abuse give owners an incentive to pay themselves more than their firms are worth and then default on their debt obligations.” The fact that paper gains from stock prices can be wiped out when financial storms occur makes financial capitalism less resilient than the industrial base of tangible capital investment.”

January 2011 press conference about the merger of Dutch private-equity company Alpinvest with the Carlyle Group. (Rembrandt17, CC BY 1.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Harvard’s McDonough notes that in the past 45 years the U.S. economy has become heavily financialized more rapidly and decisively than in our peer nations:

“Just as General Electric’s Jack Welch transformed (ruined) his company from a goods manufacturer to a financial services company, so have financial flood waters now penetrated every corner of American health care. Private equity is winning, and any health care organization is a potential takeover target. Patients and patient visits become commodities and data points to be exploited for high profits by private equity’s “financial intermediaries who view healthcare organizations as vehicles for extracting wealth.”

Don McCanne, M.D., Physicians for a Nation Health Program (PNHP), says private equity firms are moving into health care by clustering specific specialties into new corporate entities.

“These equity firms may profess to infuse quality and efficiency into the systems they create, but their true objective is not altruism. Their interest is found in their label: equity, the more ($$) the better.”

McCanne describes private equity’s modus operandi:

1) acquire a relatively large platform practice in a given specialty

2) then acquire smaller practices in the same geographic area and merge them into the platform practice

3) use debt to finance the acquisitions and assign that debt to the acquired practices,

4) find ways to increase net revenue from the agglomerated practices

5) sell the agglomerated practices within three-to-five years for considerably more than the price paid by the private equity company.

Conveniently, Dr. McCanne notes, the debt is left with the practices they purchased and the equity investors walk away with the money. How does this benefit the patients? How does this benefit the health care professionals? We know how it benefits the equity firm investors, but does anyone seriously contend that this is what health care should be about? But that’s what it has become.

Consider the consequences.

Noble Health, a private equity-backed Kansas City startup launched in 2019, acquired Audrain and Callaway Community Hospitals in rural Missouri in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. This March, all hospital services ceased with the furlough of 181 employees.

Notes Kaiser Health News, “…venture capital and private equity firm Nueterra Capital launched Noble in December 2019 with executives who had never run a hospital, including Donald R. Peterson, a co-founder who prior to joining Noble had been accused of Medicare fraud.”

The fate of St. Joseph’s Home for the Aged in Richmond, Virginia, was told in The New Yorker. A New Jersey private equity firm called the Portopiccolo Group bought the home, “reduced stuff, cut amenities and set the stage for a deadly outbreak of COVID-19” that included a doubling in patient deaths.

The numbers of stories of private equity-generated health system harm grows rapidly. And if the health part of the business goes bust, as occurred in 2019 at Philadelphia’s now closed Hahnemann Hospital, the underlying real estate still offers rich rewards.

Philadelphia’s now defunct Hahnemann University Hospital in 2010. (Scott McLeod, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Patients at North Carolina-based Atrium Health get what looks like an enticing pitch when they go to the nonprofit hospital system’s website: a payment plan from lender AccessOne. The plans offer “easy ways to make monthly payments” on medical bills, the website says. You don’t need good credit to get a loan. Everyone is approved. Nothing is reported to credit agencies. Very high interest rates are standard however.

In Minnesota, Allina Health encourages its patients to sign up for an account with MedCredit Financial Services to “consolidate your health expenses.” Very high interest.

In Southern California, Chino Valley Medical Center, part of the Prime Healthcare chain, touts “promotional financing options with the CareCredit credit card to help you get the care you need, when you need it.” As usual, very high interest rates.

As Americans are overwhelmed with medical bills, patient financing is now a multibillion-dollar business, with private equity and big banks lined up to cash in when patients and their families can’t pay for care. By one estimate from research firm IBISWorld, profit margins top 29 percent in the patient financing industry, seven times what is considered a solid hospital margin.

Mental Health Services

Headquarters of private equity company Bain Capital in Boston’s John Hancock building. (RhythmicQuietude, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The Private Equity Newsletter reports that psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers once ran their own practices. Now the local therapist office could be controlled by a buyout king.

Venture capitalists and private-equity firms are pouring billions of dollars into mental-health businesses, including psychology offices, psychiatric facilities, telehealth platforms for online therapy, new drugs, meditation apps and other digital tools.

Nine mental-health startups have reached private valuations exceeding $1 billion last year, including Cerebral Inc. and BetterUp Inc.

Demand for these services is rising as more people deal with grief, anxiety and loneliness amid lockdowns and the rising death toll of the Covid-19 pandemic, making the sector ripe for investment, according to bankers, consultants and investors.

They say the sector has become more attractive because health plans and insurers are paying higher rates than in the past for mental-health care, and virtual platforms have made it easier for clinicians to provide remote care.

“Since Covid, the need has gone through the roof,” said Kevin Taggart, managing partner at Mertz Taggart, a mergers-and-acquisitions firm focused on the behavioral-health sector. “Every mental-health company we are working for is busy. A lot of them have wait lists.”

In the first year of the pandemic, prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25 percent, the World Health Organization said in March. About one-third of Americans are reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of behavioral-health acquisitions jumped more than 35 percent to 153 in 2021 versus the previous year, and of those, 123 involved private-equity firms, according to Mertz Taggart. In the first quarter of this year, there were 41 acquisitions, of which 30 involved PE firms.

The push into mental health carries risks. A rush of private-equity firms could send prices for practices higher, reducing potential profits. A risk for patients and clinicians is that new owners could focus on profits rather than outcomes, perhaps by pressuring clinicians to see more patients than they can handle. If care becomes less personal and private, patient care might also suffer.

Online mental-health company Cerebral and other telehealth startups have begun to face scrutiny over their prescribing practices. The Wall Street Journal has reported that some of Cerebral’s nurse practitioners said they felt pressure to prescribe stimulants. Last week, Cerebral said it would pause prescribing controlled substances such as Adderall to treat ADHD in new patients. Last year, Cerebral logged a $4.8 billion valuation.

Investors poured $5.5 billion into mental-health technology startups globally last year, up 139 percent from 2020, according to a report by CB Insights, an analytics firm. Of that, $4.5 billion was spent on U.S. firms. They range from platforms like SonderMind that match people with clinicians to meditation apps like Calm.

How Bad Has It Gotten?

Private equity-owned healthcare companies have also seen the following issues:

Over-reliance on unlicensed staff to reduce labor costs

Failure to provide adequate training

Pressure on providers to provide unnecessary and potentially costly services

Violation of regulations required for participants in Medicare and Medicaid such as anti-kickback provisions, creating litigation risk

Dentistry

A Small Smiles Dental Centers clinic in Houston, 2012.

Kaiser Health News (KHC) reports that private-equity business tactics have been linked to scandalously bad care at some dental clinics that treated children from low-income families.

In early 2008, a Washington, D.C., television station aired a shocking report about a local branch of the dental chain Small Smiles that included video of screaming children strapped to straightjacket-like “papoose boards” before being anesthetized to undergo needless operations like baby root canals.

Five years later, a U.S. Senate report cited the TV exposé in voicing alarm at the “corporate practice of dentistry in the Medicaid program.” The Senate report stressed that most dentists turned away kids enrolled in Medicaid because of low payments and posed the question: How could private equity make money providing that care when others could not? The answer is “volume,” according to the Kaiser report.

Small Smiles settled several whistleblower cases in 2010 by paying the government $24 million. At the time, it was providing “business management and administrative services” to 69 clinics nationwide, according to the Justice Department. It later declared bankruptcy.

According to the 2018 lawsuit filed by his parents, Zion Gastelum was hooked up to an oxygen tank after questionable root canals and crowns “that was empty or not operating properly” and put under the watch of poorly trained staffers who didn’t recognize the blunder until it was too late.

Zion never regained consciousness and died four days later at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, the suit states. The cause of death was “undetermined,” according to the Maricopa County medical examiner’s office.

An Arizona state dental board investigation later concluded that the toddler’s care fell below standards, according to the suit. Less than a month after Zion’s death in December 2017, the dental management company Benevis LLC and its affiliated Kool Smiles clinics agreed to pay the Justice Department $24 million to settle False Claims Act lawsuits.

The government alleged that the chain performed “medically unnecessary” dental services, including baby root canals, from January 2009 through December 2011.

In their lawsuit, Zion’s parents blamed his death on corporate billing policies that enforced “production quotas for invasive procedures such as root canals and crowns” and threatened to fire or discipline dental staff “for generating less than a set dollar amount per patient.”

Kool Smiles billed Medicaid $2,604 for Zion’s care, according to the suit. FFL Partners did not respond to requests for comment. In court filings, it denied liability, arguing it did not provide “any medical services that harmed the patient.”

Olson, author of Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms U.S. Health Care, concludes, private equity does not belong in medicine at all and should it be banned.

“We really need to prohibit, I think, the corporate practice of medicine, period. If you look at the private equity playbook, its only goal is to make outsized profits – they can’t make ordinary profits. If they make ordinary, respectable profits, their investors will go somewhere else because of the risk.

Private equity doesn’t care whether the product is Roto-Rooter or hospice. That’s one of the major differences between PE and a regular company, which may care about the community, the reputation of the company, and the quality of the product. They want to keep their customers. They care about the future.

But private equity doesn’t work like that. Because private equity often aims to sell a company after four or five months, they don’t care about the future. They don’t care about the product at all. Private equity is antithetical to our health care system.

So yes, we need to ban private equity from health care. But given that it’s not going to happen, I would say that we need to prohibit the corporate practice of medicine — anybody can make a case for that.

You can eliminate their tax advantages.

You can limit the debt imposed on companies, especially in the health sector. You could easily control consolidation and monopolies in the health sector.

You could use specific anti-trust laws. I would definitely forbid investment by retail customers such as their 401(k)s.”

Also forbidden should be non-disclosure and non-disparagement agreements, which make it so difficult to obtain information. I had a hard time interviewing people for this article. When people did talk, they were extraordinarily careful.

“Stealth branding” should also be banned — where the PE firm buys a chain, like a dental chain, but gives each office its own name, like Marilyn’s Happy Dental Care. It’s very deceptive.

PE players and firms don’t tend to be household names. They’ve really managed to fly under the radar. Here are some names that came up frequently in the research; names to look out for:

Bain Capital, the PE company that Mitt Romney still profits from, is one.

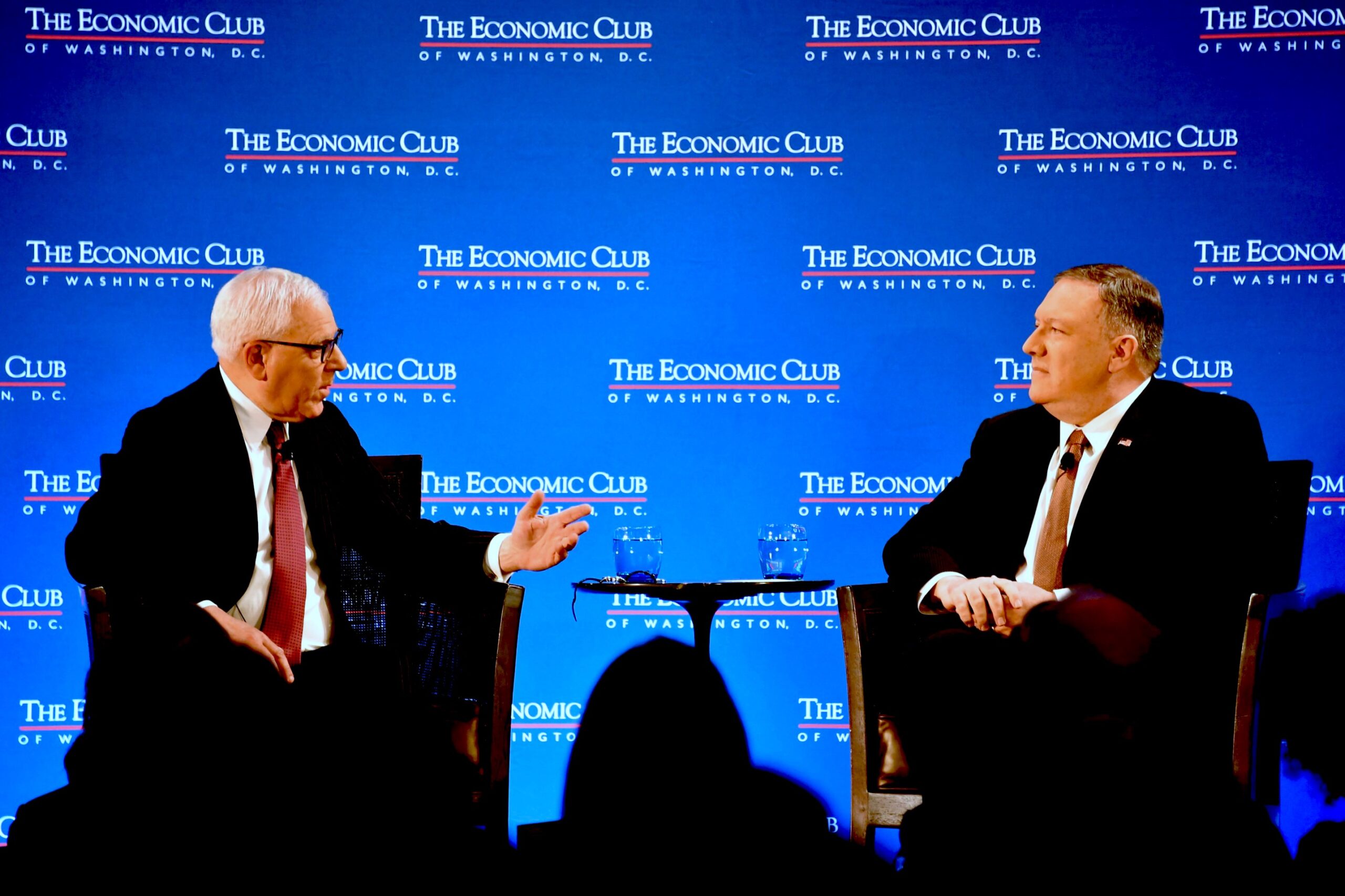

The Carlyle Group has been involved in recruiting high-ranking people from the government — one of its co-founders, David Rubenstein, served as deputy assistant to the president for domestic policy during the Carter administration. George H.W. Bush became a senior member of its Asia advisory, and so on.

July 2019: David Rubenstein, a founder of the private equity group KKR, in a discussion with U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo in Washington, D.C. (State Department, Michael Gross)

KKR, of course, is one of the biggest. They control a lot in health care.

Dr. Olson concludes with concerns that can affect all communities.

“As PE gets more and more money — with these pension funds, and especially if they get their hands into the 401(k)s — they’re just going to keep buying up anything and everything. And it’s not just health care. More and more of these firms are appearing and getting into more and more industries.

As young people, or even older people involved in the well-established financial firms, realize how much money is involved, they just start a PE firm. Look at Jared Kushner [Affinity Partners]. It’s a very worrisome situation.”

Douglas Stephenson, LCSW, is a retired psychotherapist and former instructor of social work in the University of Florida Department of Psychiatry. He is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program.

This article is from Common Dreams.

.png)