Beit Jann, Israel

In black robes, white moustaches and traditional hats, Druze religious elders stood before the coffin of Israeli soldier Adi Malik Harb, killed fighting Hamas militants in Gaza.

But while Israel’s Druze minority serve in the military and fight and die for the country, many of them say their communities are marginalised and deprived of public investment while families are fined crippling sums for building homes due to selective enforcement of planning rules.

Around 150,000 Druze, Arab adherents of an esoteric offshoot of Shia Islam, live in Israel. Most identify as Israelis and the men, not women, are conscripted into the military, many serving in combat units.

The Druze community is concentrated in 16 villages in northern Israel, among them Beit Jann, where Harb’s funeral took place on Sunday.

“Don’t Adi’s friends and acquaintances deserve to work and raise a home in Beit Jann without interference, without worrying about orders and fines?” the Druze religious leader Sheikh Mowafaq Tarif said at the funeral.

At least six Druze soldiers were among the 390 Israeli soldiers killed since the start of the war between Israel and Hamas on October 7.

That has renewed debate around the contentious Nation State law which in 2018 enshrined Israel’s primary status as a state for Jews, legislation that Druze and other Arab citizens, find denigrating.

· Demolition orders

Activists say that after decades of underinvestment Druze villagers have to contend with poor electricity networks, sewage systems and roads.

Residents are rarely granted permits to build houses, and according to Salah Abu Rukun, one of the leaders of a months-long Druze protest against demolition orders, around two-third of Druze homes in Israel were built without proper permits in recent decades, leaving them under constant threat of demolition orders or huge fines.

The Druze are “left with very limited private lands that cannot provide for the continued existence of the Druze community with its character and its villages”, he said.

Increased enforcement since a 2017 law to deter unregulated construction in recent years had become “insufferable”, he added.

Nisreen Abu Asale, a lawyer from Beit Jann, said residents were left with no choice but to live in houses without permits.

“We don’t want to leave our community, culture or religion,” she said, adding that urban planning had not moved on for decades.

“We’re living on the needs from 20 or 30 years ago.”

In practice, houses are rarely demolished, but financial penalties are enforced rigorously.

Ashraf Halabi, a basketball trainer at Haifa’s Technion University is paying off around 600,000 shekels (more than $160,000) in fines for building his home and a swimming pool, where he has held swimming classes for local youth, on his land on the outskirts of Beit Jann.

“Who needs to demolish the building, they are destroying our wallets, destroying the bank account,” he told AFP.

“We have mobilisation orders and we have demolition orders. These are the two things we excel at, unfortunately,” he added.

· “Racist and inconsiderate”

Selective enforcement of the planning laws is indicative of the increased marginalisation of non-Jewish minorities in Israel under right-wing governments in recent years, activists say.

In 2018, parliament passed the “Nation-State law” which declared that only Jews had a “right to national self determination in the State of Israel” and downgraded Arabic from an official language to one with a “special status”.

The Druze vociferously opposed the Nation-State Law. Beit Jann Mayor Radi Najam calls it a “racist, unequal and inconsiderate of anyone who isn’t Jewish”.

But the law has come under increasing scrutiny as Druze fight and die in the war.

Interior Minister Moshe Arbel last week appointed a Druze attorney to advise on the issue of planning and housing in Druze communities. On Monday, a Knesset committee green-lit 1,000 new housing units in the Druze village of Daliat al-Carmel.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Saturday that the Druze were “a precious community. They are fighting, they are falling in combat” and pledged to “give them everything they deserve”.

Majdi Hatib runs a restaurant and therapeutic horse farm outside Beit Jann, and says he served four months in prison for non-payment of building fines.

A former combat soldier, he provides an Iron Dome missile battery detachment near his land with food and showers.

“Whether it’s deliberate discrimination or not doesn’t matter to me,” he said. “Just as I fought for my country, and I love my country, I will fight for my rights.”

His house was built decades ago by his father, without a permit, and his adult son lives under the same roof.

“Whom will he wait for?” he asked. “For God? The Messiah? For them to come and solve our problems?”

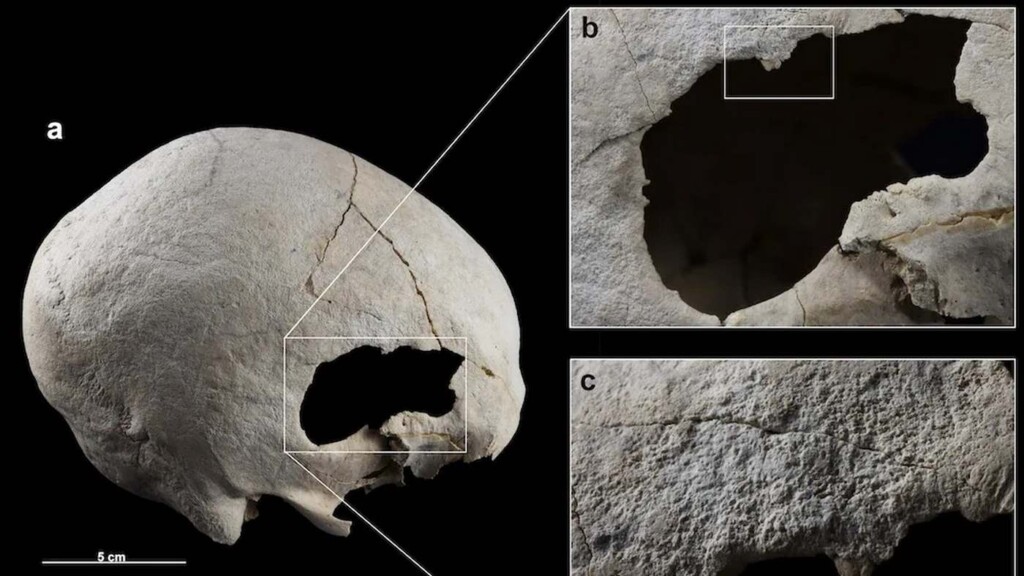

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Image credit: Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al. via Live Science)