Empowering Women: Unveiling Progress in Employment and Economic Participation

The Finance Minister of India highlighted in her budget speech 2024-25 that substantial progress has been made to empower women over the past decade. NirmalaSitharaman further emphasised in her speech that the government's targeted efforts, such as providing financial support to women through the Mudra Yojana and promoting education for women, have been instrumental in fostering increased Female Labour Force Participation (FLFP).This article aims to analyse the Finance Minister's statement, focusing on the recent rise in FLFP and its qualitative indicators.

It appears that the Minister’s statement is based on the findings of the Periodic Labour Force Survey 2022-23, which was released in October 2023. It would be relevant to provide a brief historical context of India's Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) to understand the increasing trend in female labour force participation over the years. FLFPR measures the percentage of women who are either employed or actively seeking employment within the total population of women of working age i.e.15 years and above.The Government of India began employing the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) in the fiscal year 2017-18, replacing the quinquennial Employment-Unemployment Surveys (EUS) that were previously utilised to assess the employment scenario in the country. The introduction of PLFS marked a departure from EUS, featuring distinctions in terms of survey frequency, scope, and methodology.

It is important to understand there are two major methods of measuring employment or the labour force participation rate i.e. the Usual Principal and Subsidiary Status (UPSS) and the Current Weekly Status (CWS). Due to the differences in reference periods and methodologies adopted in these two methods, data obtained from UPSS and CWS surveys exhibit variations.

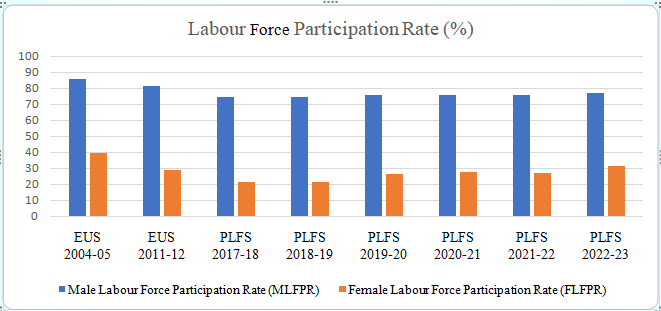

Figure: Labour Force Participation Rate (All India, age 15 years and above), CWS (in %)

EUS and PLFS Reports of Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation

The data presented in the table illustrates a decrease inLFPR from 2004-05 to 2022-23. The magnitude of the drop in LFPR from 2004-05 to 2011-12 was quitesubstantial, especially for females. Subsequently, the trend showed either a stagnation or slight increase in LFPR.

As regards the FLFPR, there was a reversal in the declining trend following 2018-19, with a significant increase observed in 2022-23.The initial decline in FLFPR observed from 2004-05 to 2017-18 has been attributed to factors such as the rising enrolment of women in schools and the relatively slow growth of employment opportunities during that period, as highlighted by several studies. According to recent reports, there has been an increase in FLFPR, particularly witnessing significant growth in 2023. The government claims this noteworthy surge in FLFP in 2022-2023 is a result of theformulation of policies and legislation for fostering women-led development.

Various studies have analysed this data to understand the qualitative aspects of this increase in FLFPR. The recent article of Ashwini Deshpande (2023) shows that the increase is driven by an increase in the proportion of rural women under the broad category of “self-employed”.Self-employed includes those who are own-account workers, employers or unpaid helpers.

The analysis of recent PFLS data further indicates that the proportion of women working as own-account workers increased, whereas the proportion of unpaid workers remained stable during 2021-22 and 2022-23. Thus, the increase in FLFPR is attributable to an increase in proportions of women working as own-account enterprises or as unpaid helpers.

In the post-COVID-19 period, the increase in FLFPR can be attributed to various factors, including the need for women to supplement household incomes due to declining wages and heightened employment uncertainty. This phenomenon reflects the income effect, where individuals, in this case, women, are motivated to join the labour force in response to economic challenges facing their households.

It is widely acknowledged that employment with longer-duration job contracts and access to social security benefits from employers are indicators of good quality employment. Data for these indicators of quality employment are collected only for regular workers which constitutes approximately 20% of total female workers. The analysis of recent PLFS reports conducted by experts indicate that there has been a significant decline in the proportion of female workers without job contracts, indicating a shift towards more secure employment arrangements. Specifically, in rural areas, the proportion decreased from 57.8% to 50.2%, while in urban areas, it declined from 71.72% to 55.61% between 2017-18 and 2022-23. Similar improvements have been recorded for both rural and urban men, suggesting a broader trend towards better quality employment across genders and locations.

Despite improvement in job contract duration of workers, there are concerning trends regarding the proportion of women in regular salaried work without social security benefits. In rural areas, the proportion of women in regular salaried work without social security benefits increased from 54.9% to 58%, indicating a rise in precarious employment conditions. Similarly, in urban areas, this proportion increased from 49.8% to 51.1%, further highlighting the vulnerability of female workers in terms of social security coverage.

Thus, it has been observed that with the increase in FLFPR,there is an enhancement in the quality of employment characterised by longer job contract duration of women workers. This leads to increased stability, productivity, and satisfaction for both employees and employers.However, this improvement in FLFPR is not accompanied by a corresponding increase in social security coverage for women salaried workers.

Overall, women in salaried employment have experienced some improvements in terms of working conditions. However, a notable challenge remains as the proportion of women in salaried employment constitutes only around 20% of the total female labour force. By highlighting this trend, the government can demonstrate their commitment to empowering women economically and creating an environment conducive to their active participation in the workforce. The government can reinforce its narrative of promoting gender equality and women's empowerment, which not only benefits individual women but also contributes to broader economic growth and social development.

The author is the Assistant Professor of Electronics at L.S.College, B.R.A. Bihar University, Muzaffarpur, Bihar.