NDP Leadership Candidate Avi Lewis Calls for ‘Public Options’ to Fight High Costs of Groceries, Housing, and Telecoms in Canada

“When people are being gouged at the checkout aisle, on their phone bills, and in their rents, it’s clear that the market is failing,” Lewis said.

HIS GRANDDAD LED THE PARTY IN THE SEVENTIES

THE ONLY NON ZIONIST IN THE FAMILY

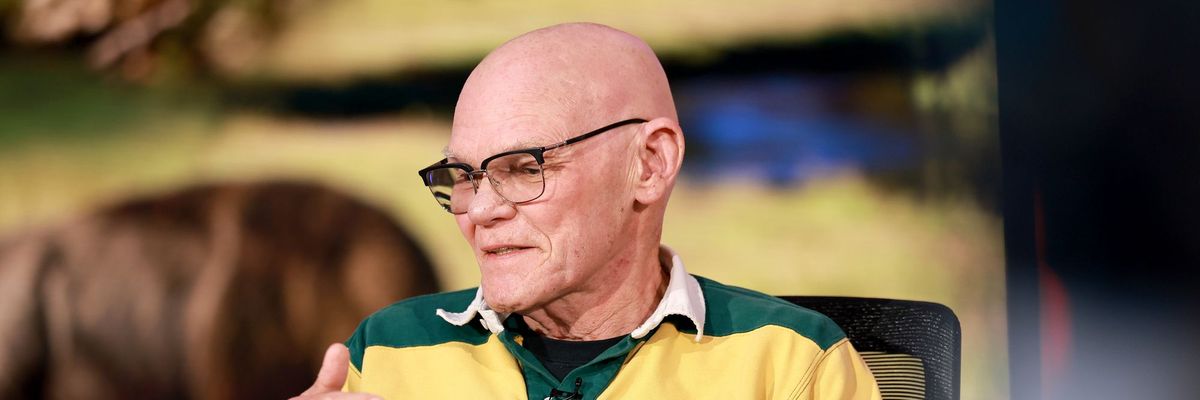

Journalist and filmmaker Avi Lewis delivers a speech at a rally as part of his campaign for leadership of Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP) in Vancouver, British Columbia, on November 19, 2025.

(Photo from the Avi Lewis campaign)

Stephen Prager

Nov 24, 2025

COMMON DREAMS

As Avi Lewis moves forward with his bid to become the next leader of Canada’s New Democratic Party, the progressive activist, filmmaker, and journalist, announced his first major policy proposal on Monday: an array of “public options” for groceries, housing, phone bills, and other necessities aimed at combating Canada’s cost-of-living crisis.

After two failed parliamentary bids in 2021 and 2025, the Vancouver-based Lewis in September launched his bid to take Canada’s leftmost party in a more economically populist direction following a series of defeats under its long-serving, Jagmeet Singh.

He hopes his laser focus on corporate greed, which he says is driving Canada’s cost-of-living crisis, will help set him apart from other front-runners, including Edmonton Member of Parliament Heather McPherson and British Columbia union leader Rob Ashton.

“It’s a moral outrage that so many people in Canada can’t afford the basics of a dignified life at a time when corporate profits are only skyrocketing,” Lewis said as he unveiled an array of new proposals Monday. “When people are being gouged at the checkout aisle, on their phone bills, and in their rents, it’s clear that the market is failing.”

Lewis called for the creation of a public not-for-profit grocery store chain that would operate coast to coast to combat the growing crisis of food insecurity.

According to data published earlier this year by the Canadian Income Survey, approximately 10 million Canadians—over 25%—lived in food-insecure households in 2024, nearly doubling since 2021 amid skyrocketing food prices.

Lewis described it as a “market failure” that so many Canadians could struggle to pay for food while Galen Weston, the owner of Canada’s largest grocery chain, Loblaw, has a net worth of over $18 billion.

Lewis called for the government to create “a low-cost alternative to the big grocery chains, using a high-volume, warehouse-style model supported by local and regional food hubs.” He likened the proposal to Mexico’s chain of state-owned grocery stores and the government-run commissaries that provide affordable food to US servicemembers and their families, both of which cost less on average than shopping at major grocery chains.

“Think Costco—but run as a public service,” Lewis explained in a policy document.

Lewis proposed a similar solution for the cost of cell phone and internet service, which are higher in Canada than in other peer countries.

Attributing this to “an oligopoly of telecom providers that dominate cellphone and internet services in Canada and gobble up smaller competitors,” he proposed that the nation create a network of public telecom providers modeled after SaskTel. This publicly owned company serves the province of Saskatchewan and has led to “substantially lower” prices for customers than in other parts of Canada, according to the nation’s Competition Bureau.

To combat the spiking cost of rent and a growing homelessness crisis, Lewis also pledged that his NDP would once again prioritize the construction of public housing, which Canada built prolifically until the early 1990s.

He pledged that under his leadership, Canada would establish a public builder to create a million new units of social, co-op, non-profit, and supportive homes within five years.

Lewis also championed the return of nationwide postal banking as an antidote to the predatory fees and interest rates of Canada’s financial institutions.

He plans to leverage the nation’s national postal service, which is already the only option for financial services in many remote parts of the country, as a competitive alternative to Canada’s six largest banks, which brought in more than $50 billion in profits last year, and to predatory payday loan and check-cashing companies.

Finally, he proposed the reestablishment of Canada’s government-owned nonprofit pharmaceutical company, Connaught Labs, which created and cheaply mass-produced life-saving vaccines and other medications like insulin for free public distribution. The company was privatized in the 1980s under former Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

“During the Covid pandemic, for-profit pharmaceutical companies made billions while countries competed with one another for vaccine supplies instead of distributing them globally to stop the virus’s spread across borders,” Lewis said.

He said that his new version of Connaught would invest in the public development of innovative pharmaceuticals, such as mRNA vaccines and cancer immunotherapies, and share that technology with low-income countries.

“It’s time to take the power back from the price-fixing corporate cartels that have a stranglehold on our economy and put it in the hands of the people,” Lewis said. “It’s time to build a new generation of public options to reduce costs and raise our quality of life.”

Lewis described his “next generation” of public options as following in the footsteps of those pursued by NDP-led provincial governments.

“Whether it’s public auto insurance in Manitoba, the agricultural land reserve to protect food security in British Columbia, a public telecom provider in Saskatchewan, or, of course, Medicare, our party has created public institutions that continue to make people’s lives better and more affordable decades after their creation.”

“The cost of living crisis we face today demands bold solutions,” he added. “That means expanding public ownership to lower bills and improve services while creating good union jobs in the process.”

Jul 21, 2017 ... His son Stephen Lewis, is a former Ontario NDP leader who served as the United Nations Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. His other son, ...

The only Jew to lead a national party in Canada, David campaigned against “corporate welfare bums” and paved the way for parliamentary acceptance of acts ...

Apr 20, 2021 ... This country's greatest political orator is battling abdominal cancer as he continues to fight for causes near and dear to his heart.

Jun 4, 2021 ... During the convocation ceremony that day, Lewis, who was receiving the first of his 42 honorary degrees, spoke to graduates and their families ...

Information about MPP Stephen Lewis.

Apr 9, 2016 ... Stephen Lewis (the former leader of the Ontario NDP and the co-founder of the Stephen Lewis Foundation) addresses the NDP National ...

Aug 25, 2015 ... For the first time in our history, Canadians can elect a truly progressive federal government. Tom Mulcair is a strong, experienced, and principled leader.

May 1, 2022 ... Back in 1977, when this family photo was published in the Toronto Star, Stephen Lewis was leader of Ontario's New Democratic Party. Lewis, who .