The world is closer than ever to a new hellish “hothouse world” as it approaches a “point of no return” after which runaway global heating cannot be stopped, scientists warn, the Guardian reported on February 11.

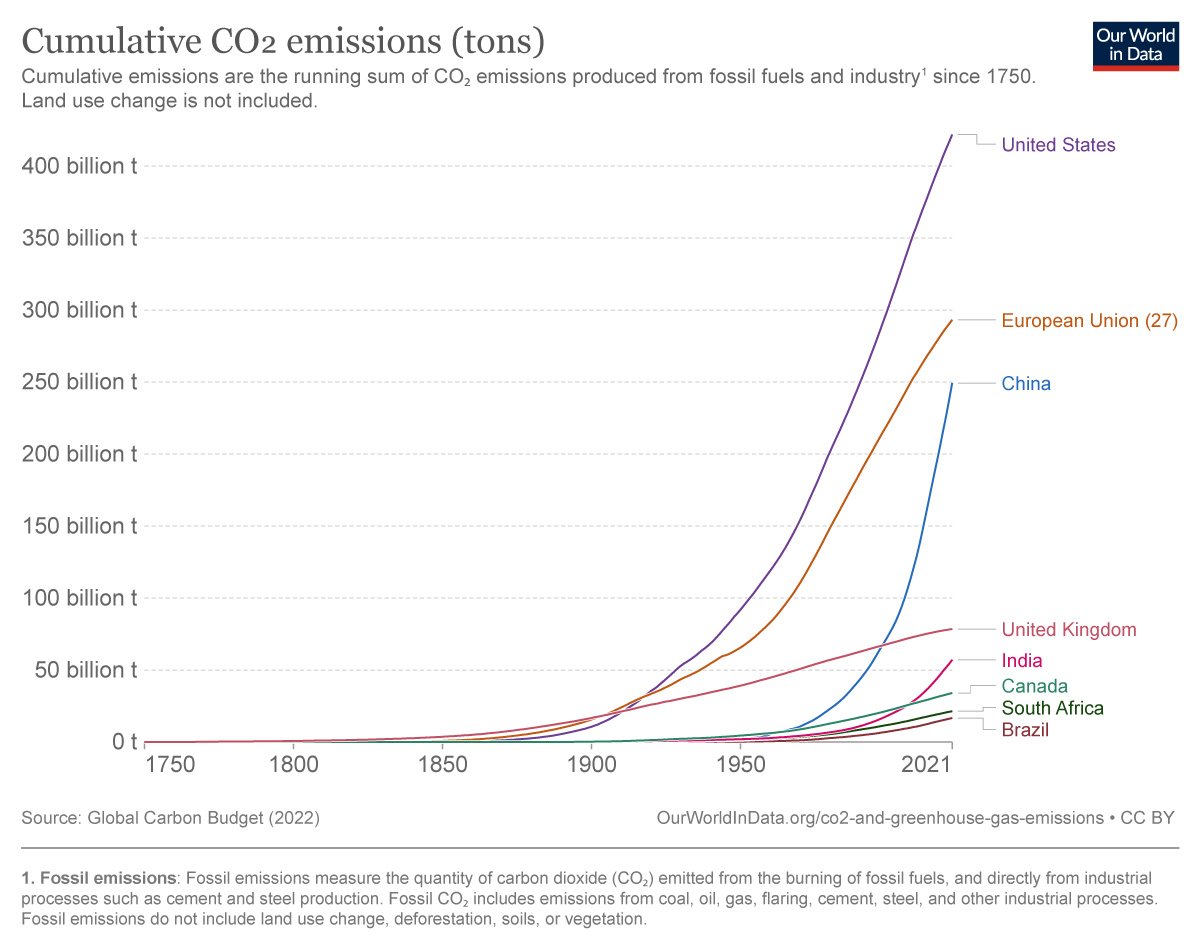

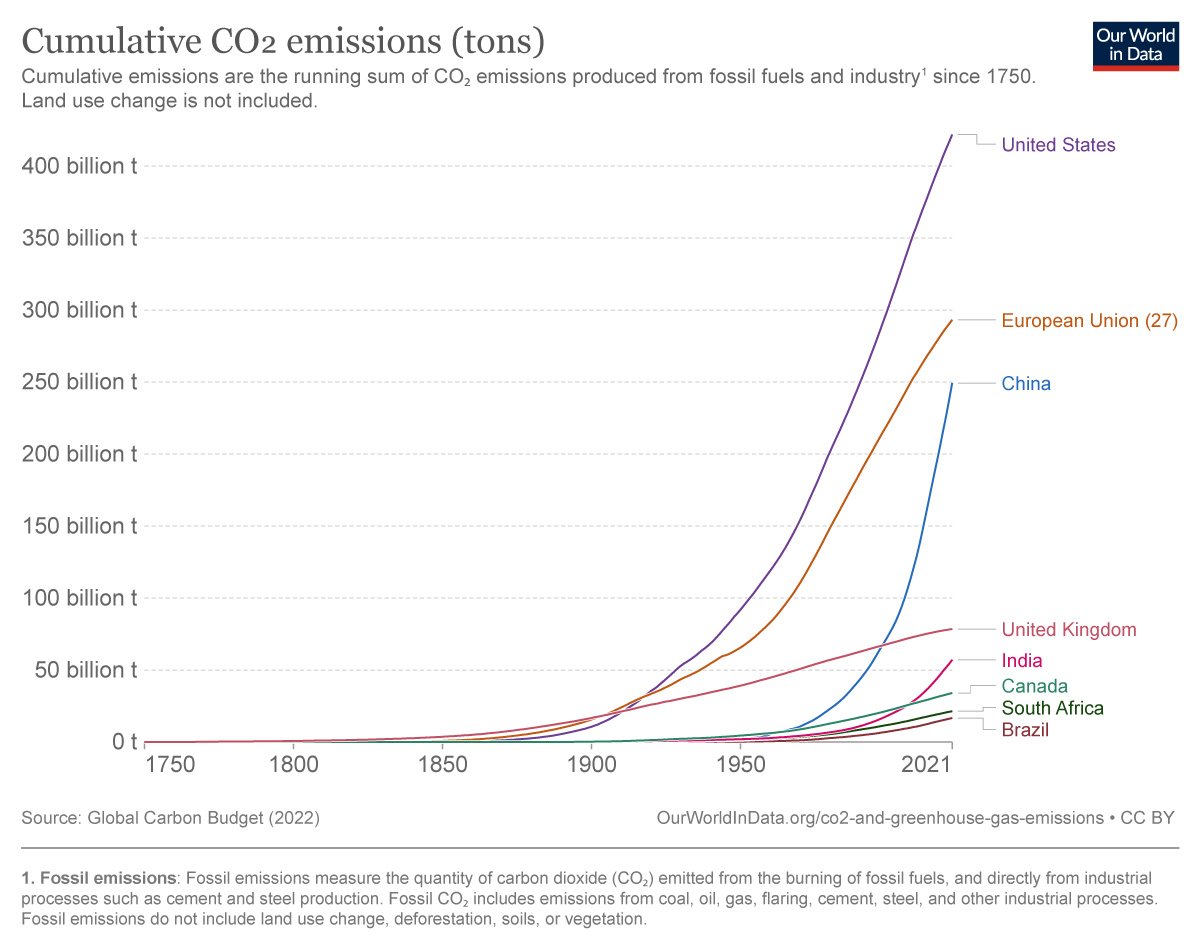

The warning comes as China and India report the first sustained emissions decrease, years ahead of schedule, but the US continues to ignore its carbon budget limits set by the 2015 Paris Agreement and has significantly increased CO₂ emissions – double those of China and India combined.

As bne IntelliNews reported, all the warning signals are flashing red as a raft of tipping points approaches after which positive feedback loops kick in and cause run-away heating that can’t be stopped.

The problems are getting acute as extreme weather events have become an annual disaster season for the last three years. Consultants McKinsey said in a recent report that the world spent $190bn on climate damage last year, but that will rise to $1.2 trillion – more than a six-fold increase – by 2030, and will continue to rise from there. Ratings agency Fitch also warned that countries exposed to extreme weather or that remain heavily dependent on hydrocarbons face sovereign debt downgrades by several notches from 2035 onwards unless they take action to mitigate their exposure now in an environmental damage impact report released last week.

Scientists are becoming increasingly alarmed at the lack of action, especially after the last three UN COP conferences to address the Climate Crisis – COP28, COP29, and COP30 -- failed to take any action.

Failing to halt emissions and curb warming will lead to “a new and hellish “hothouse Earth” climate far worse than the 2-3°C temperature rise the world is on track to reach,” the Guardian reports.

As bne IntelliNews reported, the Climate Crisis is accelerating. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that the Paris Agreement goal of keeping temperature increases to less than 1.5°C-2°C above the pre-industrial benchmark has already been missed. Temperature increases are on course to reach a catastrophic 2.7C-3.1C by 2050. At that point extreme temperature events will become routine and large parts of the world will become uninhabitable as global warming becomes irreversible due to positive feedback loops. Currently global warming is accelerating faster than all the 30-plus climate models used at the Paris meeting to set the rates and volumes of emission reduction goals. That suggests those goals should be dramatically increased, yet countries like the US are ignoring even their modest Paris targets, with the notable exception of China that has become a global green energy champion.

This new climate, which could arrive as soon as the middle of this century, would be very different to the benign conditions of the past 11,000 years, during which the whole of human civilization developed and could cause hundreds of millions of deaths in the most climate-exposed or underdeveloped parts of the world. Heat stress already killed thousands of people in Europe last summer, but if “wet-bulb” conditions are reached (35°C, 100% humidity, for six hours) then no one without air conditioning can survive outdoors. Wet bulb conditions have already been observed in places like Pakistan and UAE last year, but not for the full six hours.

Last year, studies calculating the role of the climate crisis in what are now unnatural disasters show 550 heatwaves, floods, storms, droughts and wildfires have been made significantly more severe or more frequent by global heating.

A comprehensive database of hundreds of studies that analyse the role of global heating in extreme weather was compiled by the website Carbon Brief provides overwhelming proof that the climate emergency is here today, taking lives and livelihoods in all corners of the world, the Guardian reports.

Despite the mounting evidence of the annual catastrophes, the public and politicians remain largely unaware of the severity of the mounting crisis, said the scientists. The group, led by Dr Christopher Wolf, a scientist at Terrestrial Ecosystems Research Associates in the US, said they were issuing their warning because while rapid and immediate cuts to fossil fuel burning were challenging, reversing course was likely to be impossible once on the path to a Hothouse Earth, even if emissions were eventually slashed, the Guardian reports. The team also includes Prof Johan Rockström at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany and Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria.

“Crossing even some of the thresholds could commit the planet to a hothouse trajectory,” said Wolf. “Policymakers and the public remain largely unaware of the risks posed by what would effectively be a point-of-no-return transition.

Romania’s emissions plunge 75% since communism

Some countries are stepping up to the challenge, although too few to reverse the accelerating warming trend. China and India stand out with Romania the best performer in Europe.

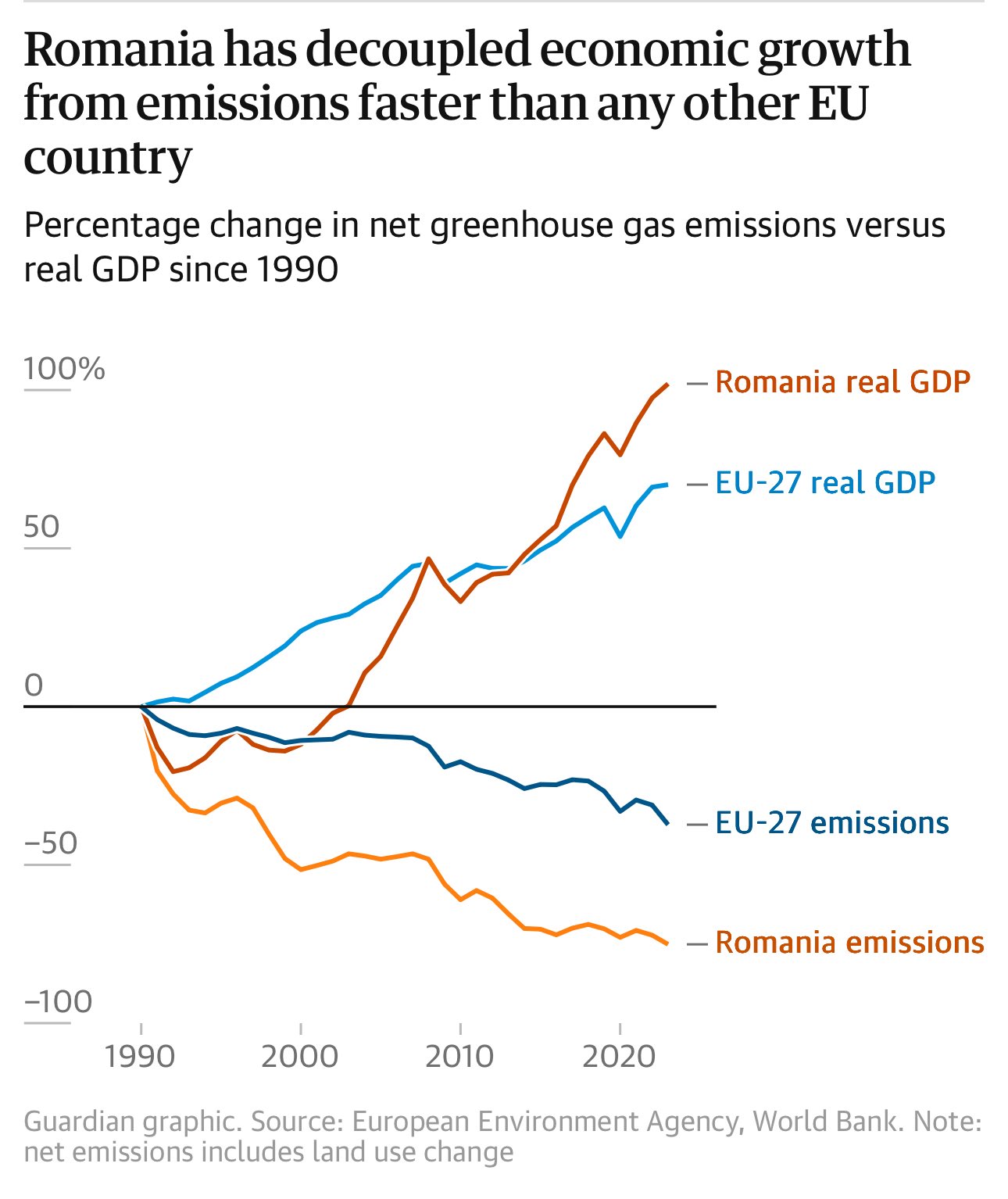

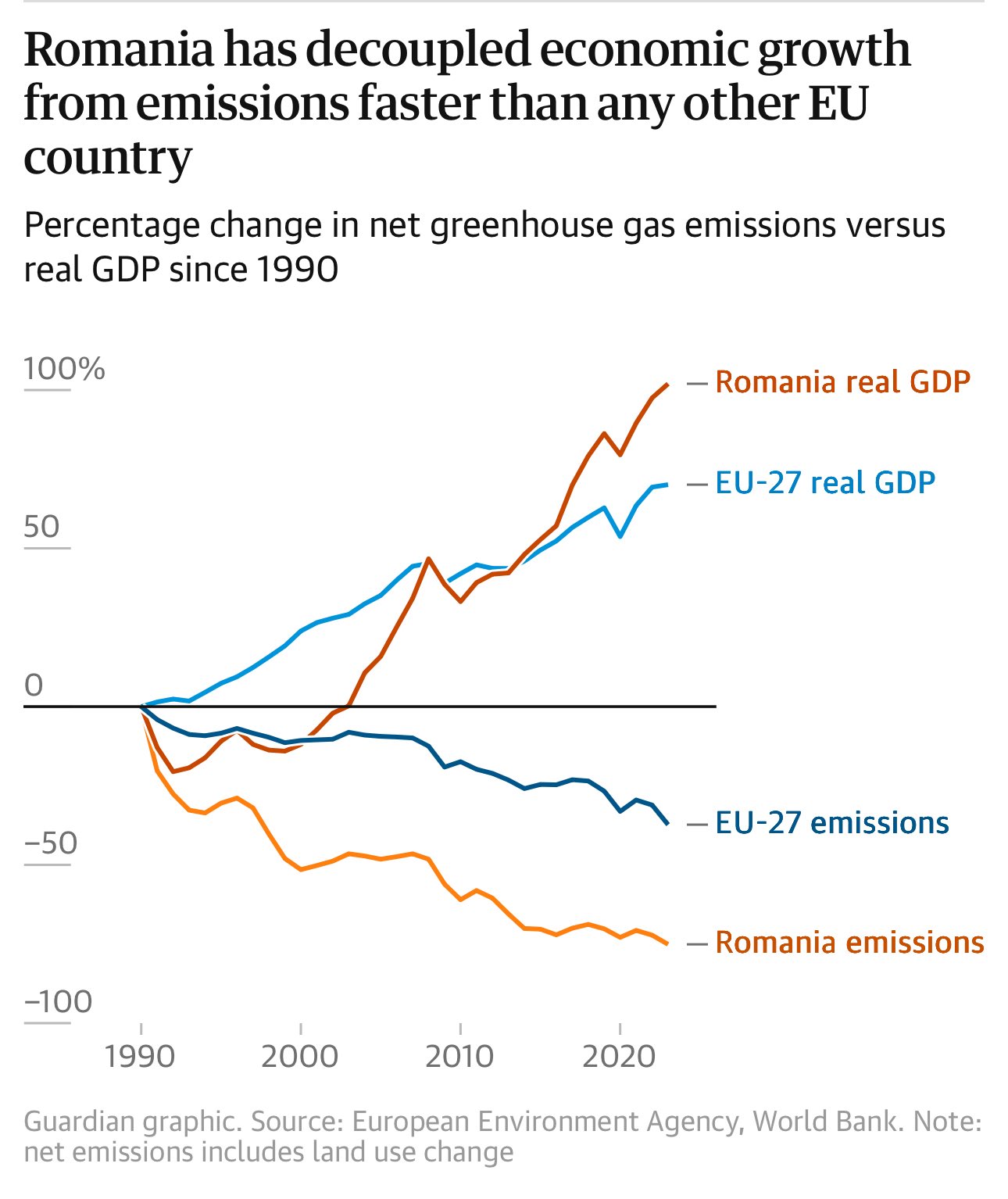

Romania has cut greenhouse gas emissions by 75% since the fall of communism, achieving one of the fastest decoupling’s of economic growth from carbon pollution in Europe even as parts of the transition have proved socially painful.

Net emissions intensity — the amount of greenhouse gases per dollar of economic output — fell by 88% between 1990 and 2023, meaning each dollar of activity now produces almost 10-times less warming pollution than at the end of the Nicolae Ceaușescu era. Over the same period, real GDP has doubled.

Once emblematic of heavy industry and low-grade lignite, Romania is now expanding renewables at pace. In southern Romania, workers are preparing to assemble what developers describe as Europe’s largest solar farm, a 760MW project comprising one million photovoltaic panels and battery storage. In the north-west, authorities have approved a 1GW plant. The country already hosts a major onshore windfarm near the Black Sea and operates the Cernavodă nuclear power plant on the Danube, whose lifetime is being extended by 30 years.

The initial collapse in emissions followed the violent end of Ceaușescu’s rule in 1989, when privatisation led to factory closures and a sharp contraction in heavy industry. But since then the government has embraced renewables as the cost of generation, and more recently battery storage tumbled, making green power the cheapest option available.

Accession to the European Union in 2007 imposed stricter environmental standards and integrated Romania into the bloc’s emissions trading system. Revenues from the EU’s modernisation fund supported grid upgrades and cleaner generation. In the 17 years after 1990, the carbon intensity of Romania’s power sector fell by 9.2%; in the following 17 years, it dropped by 52%.

Romania’s rapid decarbonisation highlights limits of ‘low-hanging fruit’ Romania’s sharp fall in greenhouse gas emissions since the end of communism offers a striking example of how quickly economies can decouple growth from carbon, but analysts warn that much of the easiest progress may already have been made.

If industrialised countries could decouple as rapidly as Romania — while avoiding the social dislocation it endured — the task of limiting climate breakdown “may not seem so hopeless”, The Guardian reported.

An analysis by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) found that countries representing 92% of the global economy have either fully decoupled economic growth from emissions, including those embedded in imports, or achieved relative decoupling, where emissions rise more slowly than output.

Yet the pace remains insufficient to meet international targets. A 2023 study of 36 advanced economies found that 11 had fully broken the link between GDP and CO₂ emissions, but none had reduced emissions quickly enough to align with their share of the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5C.

Much of the early progress has come from the power sector, where coal-fired generation has been replaced by renewables and gas. However, progress has faced several major setbacks. The US has withdrawn from the Paris Agreements and is accelerating fossil fuels exploitation. The EU has also begun to roll back elements of its Green Deal in the face of economic stagnation and higher energy costs after Russian gas imports were cut off.

The ECIU identified nine countries that had absolutely decoupled in the decade before the 2015 Paris agreement but reversed progress in the following decade. Among them are Latvia and Lithuania, whose post-Soviet trajectories resembled Romania’s initial industrial contraction followed by EU-driven expansion. Russia, by contrast, increased emissions after the collapse of the Soviet Union, doubling down on the large extractive oil and gas sector, coupled with a highly inefficient use of those resources domestically.

China maintains the lead

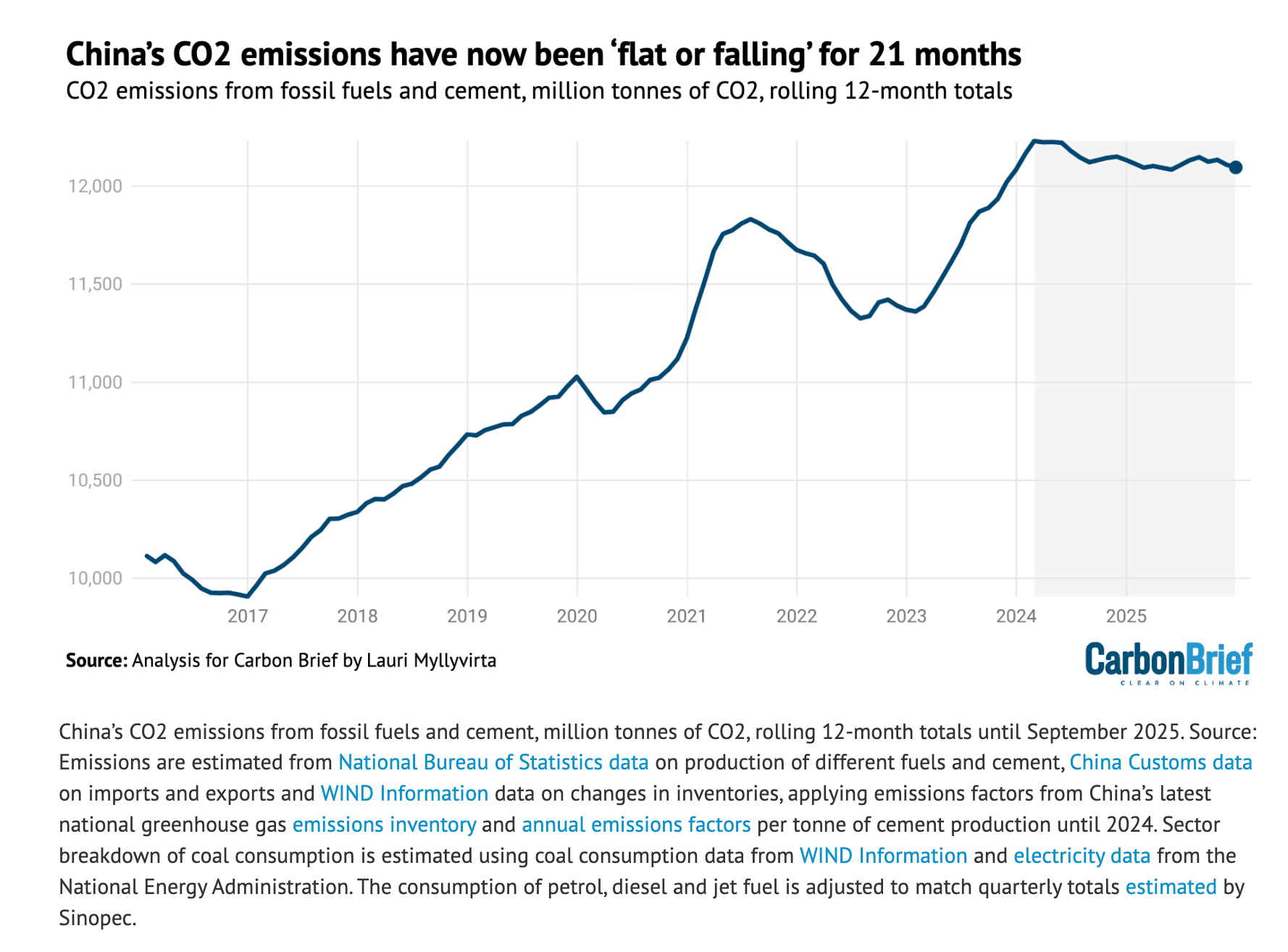

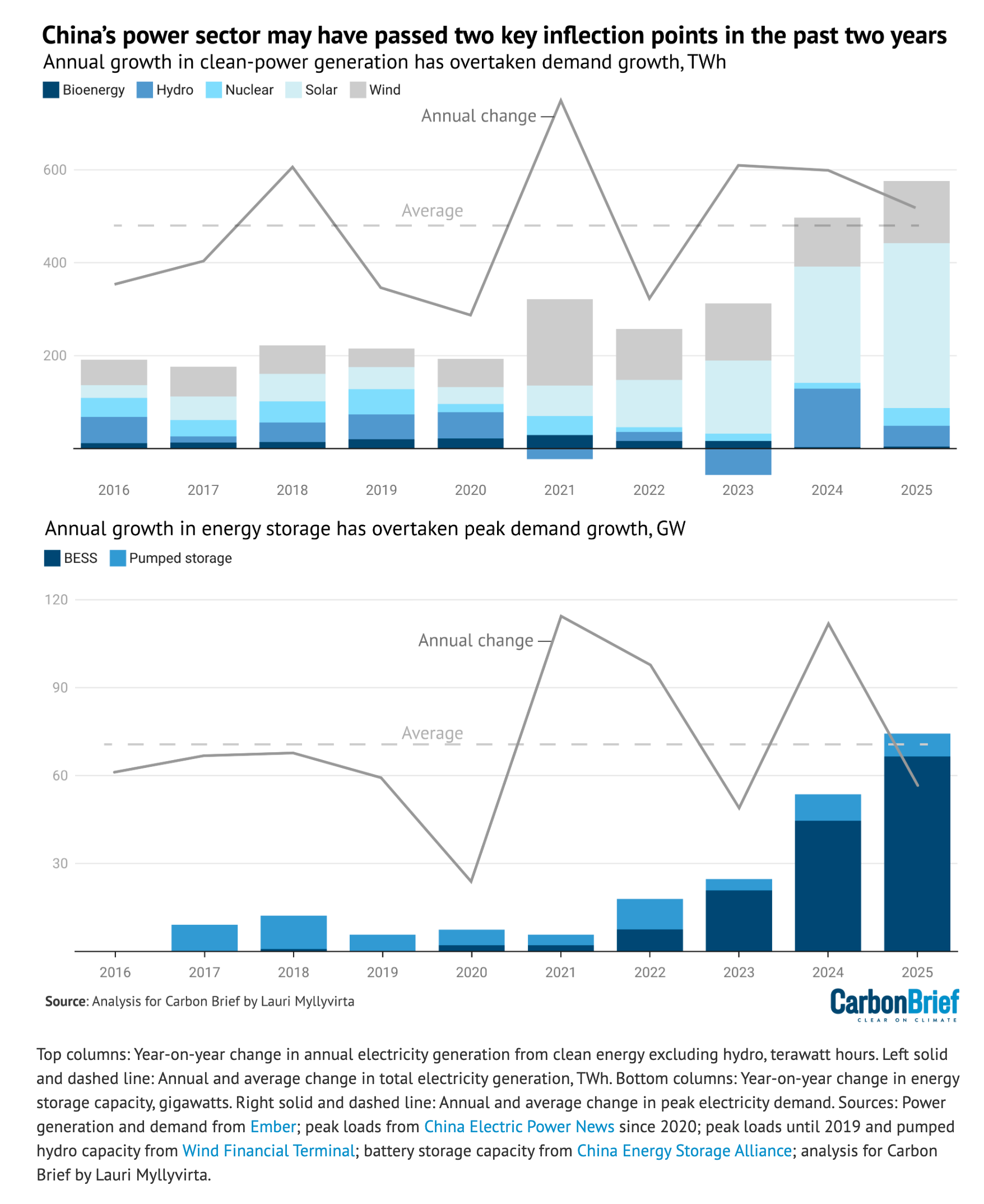

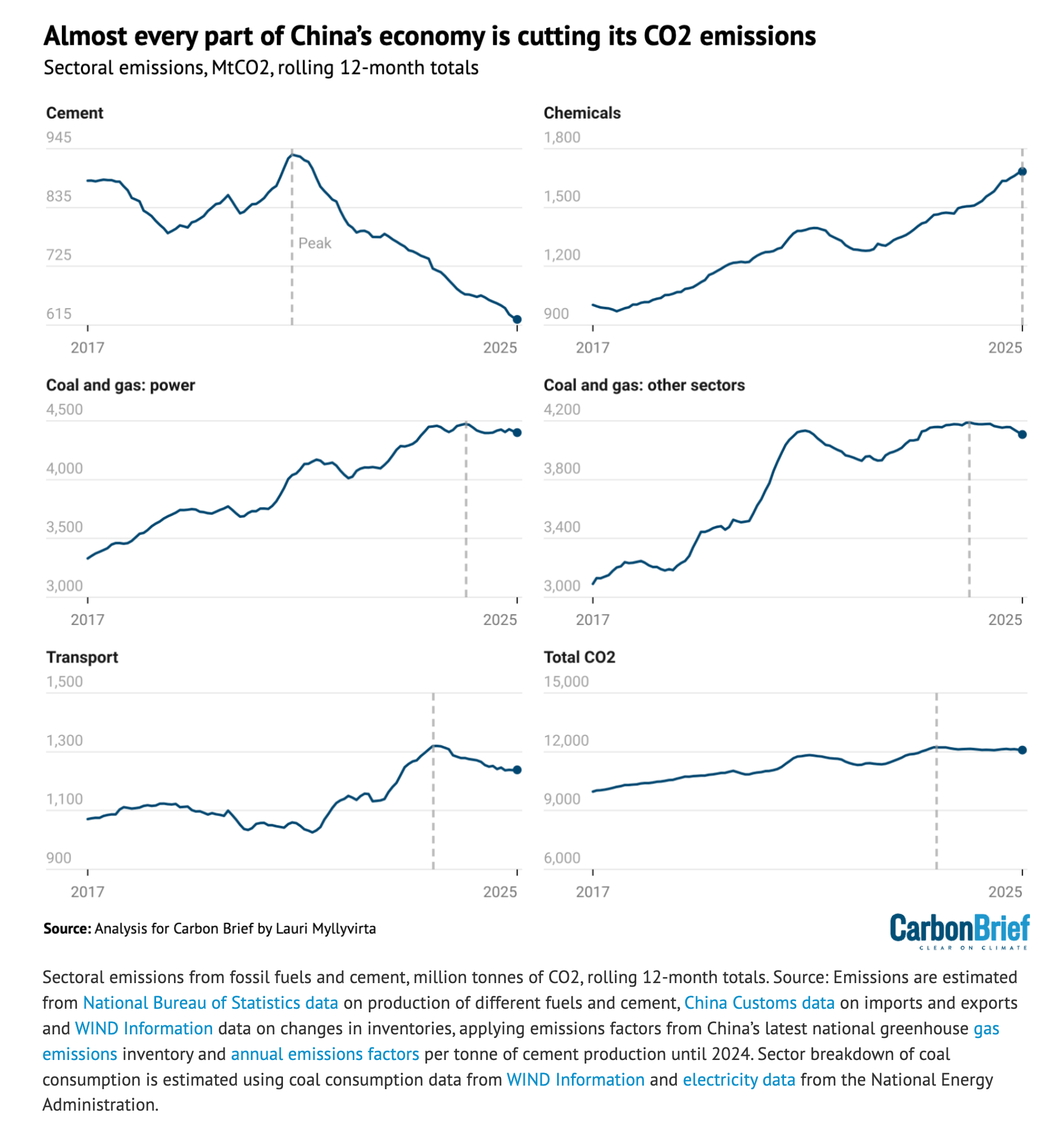

China remains head and shoulders above the rest of the world in progress towards decarbonisation. Emissions have been flat for 21 months in a row thanks to a surge in clean power curbs coal use, as rapid growth in solar, wind and nuclear power displace coal generation in the world’s largest emitter, according to analysis published by Carbon Brief.

Solar power “increased by 43% year-on-year, wind by 14% and nuclear 8%, helping push down coal generation by 1.9%.” The expansion of low-carbon electricity has coincided with a slowdown in power-sector emissions growth, despite rising demand from industry and electrification.

The analysis notes that “Energy storage capacity grew by a record 75 gigawatts (GW), well ahead of the rise in peak demand of 55GW).” The build-out of battery storage has improved grid flexibility, enabled higher penetration of intermittent renewables and reduced reliance on coal-fired peaking plants.

But despite the progress, the race is still on. China’s key climate commitments for the next five-year period until 2030 are to peak CO₂ emissions and to reduce carbon intensity by more than 65% from 2005 levels. The latter target requires limiting CO₂ emissions at or below their 2025 level in 2030.

The record clean-energy additions in 2023-25 have barely sufficed to stabilise power-sector emissions, showing that if rapid growth in power demand continues, meeting the 2030 targets requires keeping clean-energy additions close to 2025 levels over the next five years.

China’s central government continues to telegraph a much lower level of ambition, with the national plan setting a target of “around” 30% of power generation in 2030 coming from solar and wind, up from around 22% in 2025, Carbon Brief reports.

If electricity demand grows in line with the State Grid forecast of 5.6% per year, then limiting the share of wind and solar to 30% would leave space for fossil-fuel generation to grow at 3% per year from 2025 to 2030, even after increases from nuclear and hydropower. But even that level of increase would mean missing China’s Paris commitments for 2030.

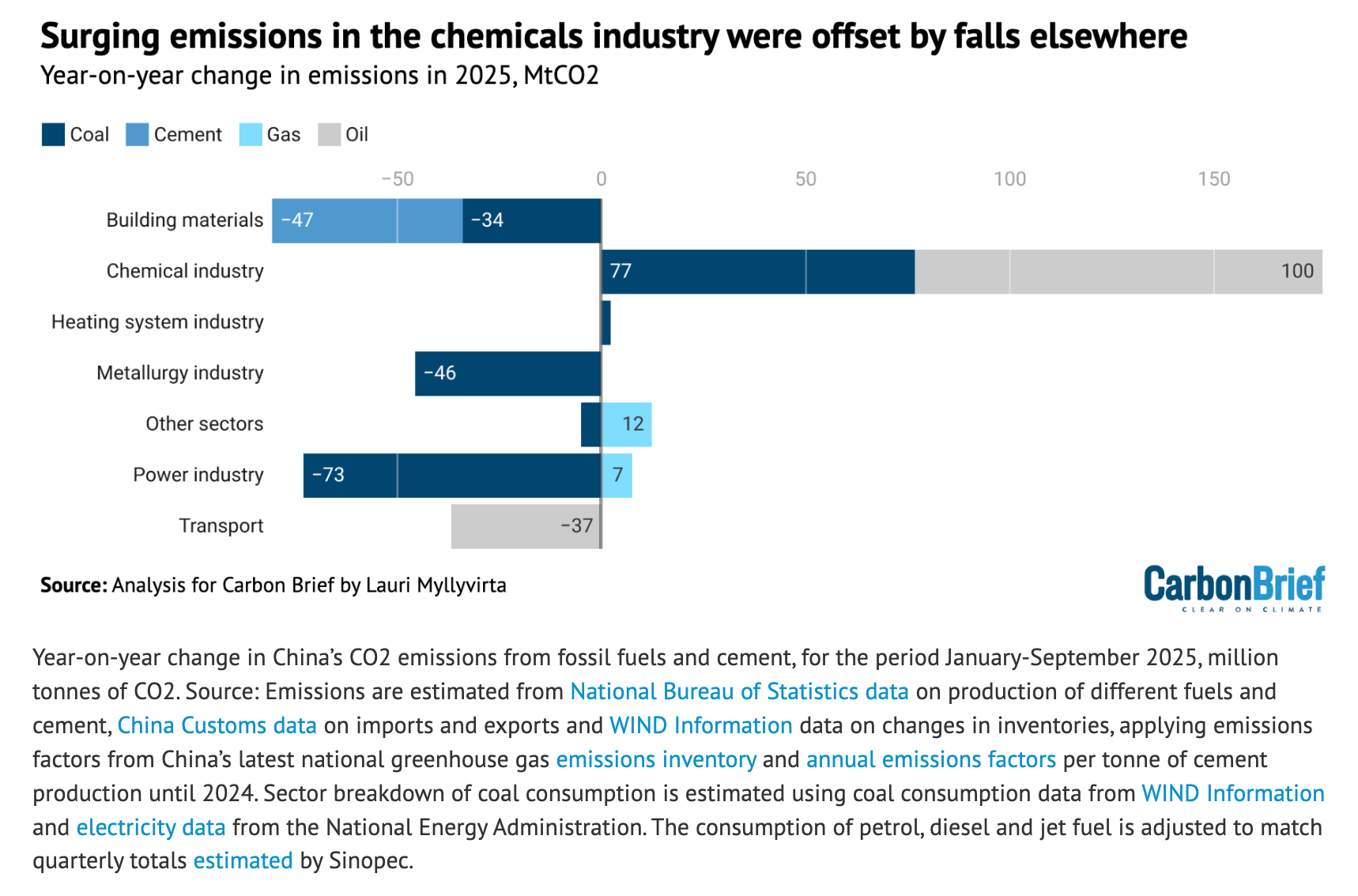

Nevertheless, every part of the Chinese economy is reducing emissions, with the exception of the chemical sector as it seeks to go up the value chain. Even though chemical-industry emissions are small relative to other sectors – at roughly 13% of China’s total – the pace of expansion is creating an outsize impact.

Without the increase from the chemicals sector, China’s total CO₂ emissions would have fallen by an estimated 2%, instead of the 0.3% reported by Carbon Brief.

The most important signal will be whether the top-level five-year plan for 2026-30, due in March, sets a carbon intensity target aligned with the 2030 Paris commitment. Officially, China is sticking to the timeline of peaking CO₂ emissions “before 2030”, which was announced by president Xi Jinping in 2020.

Complementing China’s trend, India has also recorded a fall in power-sector emissions, marking the first simultaneous decline in electricity-related carbon output in the two countries in more than five decades. Reuters reported on January 27 that power-sector emissions in China and India “declined simultaneously for the first time in 52 years”, citing a report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

“The fall in emissions in China and India in 2025 is a sign of things to come, as both countries added a record amount of new clean-power generation last year, which was more than sufficient to meet rising demand,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at CREA. Despite their status as leading emitters, both China and India remain inside the allowances for emissions granted in their carbon budgets by the Paris Accords, while the US has used up more than double its allotment. Between them, the three largest emitters — China, India and the US — account for about 60% of global power-sector emissions, which themselves represent roughly 35% of total greenhouse gas output.

Over the decade to 2024, however, power plant emissions rose 3.4% annually on average in China and 4.4% in India, underlining the structural reliance on coal in both economies.

China remains heavily dependent on coal, which still accounts for roughly 60% of electricity generation, according to official data. However, the scale and pace of clean energy deployment are reshaping the country’s power mix. China installed more solar capacity in 2023 and 2024 than the rest of the world combined, driven by falling module costs, supportive industrial policy and energy security concerns.

The flattening of emissions follows a period of volatility linked to post-pandemic economic reopening and drought conditions that constrained hydropower output. Analysts at Carbon Brief attribute the sustained plateau primarily to structural changes in the energy system rather than cyclical weakness.

Beijing has pledged to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. The recent data suggest the peak in power-sector emissions may arrive earlier than expected if renewable additions continue to outpace demand growth.

However, heavy industry, including steel and cement, remains carbon intensive, and coal approvals surged in 2022 and 2023 amid concerns over energy security. Whether the current emissions plateau marks a definitive turning point will depend on continued clean energy deployment and policy support during China’s next five-year plan period.