Dominique, the giant housefly in Mandibles, a French-Belgian comedy film written and directed by Quentin Dupieux. Photograph: Lifestyle pictures/Alamy

Creepy-crawlies usually signify death, decay and evil in films – there’s a vast canon going back decades. But has the ‘When Insects Attack’ sub-genre had its day?

Anne Billson

Fri 3 Sep 2021

In Quentin Dupieux’s Mandibles, a pair of chuckleheads called Manu and Jean-Gab (think Dumb and Dumber, but French) steal a Mercedes and find, in the boot, a housefly the size of a pitbull. They name it Dominique and train it to rob banks. At no point do they find it scary, even after it eats a dog. It’s so endearing, you will share their feelings.

This is a turn up for the books, since flies in cinema are more usually signifiers of death, decay and evil. Sometimes, as when Annie Graham goes up to the attic in Hereditary, their presence presages the discovery of a cadaver. They buzz symbolically around the grubby cheesecloth-wrapped bundle in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, while Father Delaney’s attempts to bless the cursed house in The Amityville Horror are thwarted by demonic bluebottles. In Phenomena, Jennifer Connelly plays a schoolgirl insect-whisperer who can summon flies for protection, but that doesn’t save her from getting submerged up to her neck in maggots. In the bonkers Indian action-fantasy Eega, a man murdered by his love rival is reincarnated as a vengeful housefly, but fusing your molecules with those of a Musca domestica is more likely to end in loss of vital anatomical parts, as happens in both the 1958 and 1986 versions of The Fly. (Help meeee!)

At best, insects in films are pesky. At worst, they can be downright malevolent, reflecting western society’s attitude to creepy-crawlies in general. It’s estimated that 6% of humans suffer from some form of entomophobia – and for the purposes of this article I am grouping arthropods (spiders, centipedes), gastropods (slugs, snails) and non-arthropod invertebrates (worms) under the broader entomological banner. In the immortal words of the tagline on Shaun Hutson’s novel Slugs: “They ooze. They slime. They kill.” Depending on number of legs or wings, they also creep, hop, scuttle and dive bomb. They can be trained to kill, like the lethal lepidopterans in Tsui Hark’s directing debut, The Butterfly Murders, which behave more like Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds than the colourful flitterers we know and love, while The Abominable Dr Phibes manoeuvres a biblical mini-plague of locusts into gnawing the flesh off one of his victims by dripping mashed-up Brussels sprouts over her as she sleeps.

Creepy-crawlies usually signify death, decay and evil in films – there’s a vast canon going back decades. But has the ‘When Insects Attack’ sub-genre had its day?

Anne Billson

Fri 3 Sep 2021

In Quentin Dupieux’s Mandibles, a pair of chuckleheads called Manu and Jean-Gab (think Dumb and Dumber, but French) steal a Mercedes and find, in the boot, a housefly the size of a pitbull. They name it Dominique and train it to rob banks. At no point do they find it scary, even after it eats a dog. It’s so endearing, you will share their feelings.

This is a turn up for the books, since flies in cinema are more usually signifiers of death, decay and evil. Sometimes, as when Annie Graham goes up to the attic in Hereditary, their presence presages the discovery of a cadaver. They buzz symbolically around the grubby cheesecloth-wrapped bundle in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, while Father Delaney’s attempts to bless the cursed house in The Amityville Horror are thwarted by demonic bluebottles. In Phenomena, Jennifer Connelly plays a schoolgirl insect-whisperer who can summon flies for protection, but that doesn’t save her from getting submerged up to her neck in maggots. In the bonkers Indian action-fantasy Eega, a man murdered by his love rival is reincarnated as a vengeful housefly, but fusing your molecules with those of a Musca domestica is more likely to end in loss of vital anatomical parts, as happens in both the 1958 and 1986 versions of The Fly. (Help meeee!)

At best, insects in films are pesky. At worst, they can be downright malevolent, reflecting western society’s attitude to creepy-crawlies in general. It’s estimated that 6% of humans suffer from some form of entomophobia – and for the purposes of this article I am grouping arthropods (spiders, centipedes), gastropods (slugs, snails) and non-arthropod invertebrates (worms) under the broader entomological banner. In the immortal words of the tagline on Shaun Hutson’s novel Slugs: “They ooze. They slime. They kill.” Depending on number of legs or wings, they also creep, hop, scuttle and dive bomb. They can be trained to kill, like the lethal lepidopterans in Tsui Hark’s directing debut, The Butterfly Murders, which behave more like Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds than the colourful flitterers we know and love, while The Abominable Dr Phibes manoeuvres a biblical mini-plague of locusts into gnawing the flesh off one of his victims by dripping mashed-up Brussels sprouts over her as she sleeps.

The Xenomorph in Alien (1979) exhibits insect characteristics: egg-laying queen, parasitic behaviour and metamorphic lifecycles.

Photograph: 20th Century Fox/Allstar

Why do insects make our skin crawl? Perhaps because they are hard to anthropomorphise. They are not furry and you don’t want them sleeping on your bed, though I daresay there are plenty of phasmid fanciers who have formed close relationships with their pets. With their bug eyes and exoskeletons, insects already look semi-alien, so it’s little wonder that film-makers regularly depict our planet attacked by creepy-crawlies from outer space or alternative dimensions, in films such as The Mist or the horror-comedy Infestation (which featured alien insectoids using sound to home in on their prey a decade before A Quiet Place). The Xenomorph in the Alien franchise exhibits insect characteristics (an egg-laying queen, parasitic behaviour, metamorphic life cycles), and the Martians in Quatermass and the Pit, at first mistaken for the devil, are glimpsed in atavistic memory clips hopping around like giant locusts, which ought to be funny – but somehow isn’t, especially once you learn they are engaged in a form of ethnic cleansing. As Seth Brundle says in The Fly: “Have you ever heard of insect politics? Neither have I.”

Why do insects make our skin crawl? Perhaps because they are hard to anthropomorphise. They are not furry and you don’t want them sleeping on your bed, though I daresay there are plenty of phasmid fanciers who have formed close relationships with their pets. With their bug eyes and exoskeletons, insects already look semi-alien, so it’s little wonder that film-makers regularly depict our planet attacked by creepy-crawlies from outer space or alternative dimensions, in films such as The Mist or the horror-comedy Infestation (which featured alien insectoids using sound to home in on their prey a decade before A Quiet Place). The Xenomorph in the Alien franchise exhibits insect characteristics (an egg-laying queen, parasitic behaviour, metamorphic life cycles), and the Martians in Quatermass and the Pit, at first mistaken for the devil, are glimpsed in atavistic memory clips hopping around like giant locusts, which ought to be funny – but somehow isn’t, especially once you learn they are engaged in a form of ethnic cleansing. As Seth Brundle says in The Fly: “Have you ever heard of insect politics? Neither have I.”

Creature features are usually constructed around the premise that hey, if people are freaked out by woodlice and earwigs, imagine how scared they’ll be if those critters are mutated by radiation or pollution into colossal versions that can decapitate you with one swipe of a mandible (Starship Troopers) or use brutish giant cockroach strength to fold you in half, like Ivan the luckless waiter in Men in Black. And, of course, you wouldn’t want to run into Shelob, the giant spider from Lord of the Rings, or The Deadly Mantis, Tarantula, the giant bees from Mysterious Island or the enormous parasites from Cloverfield that can make your head explode with just one bite.

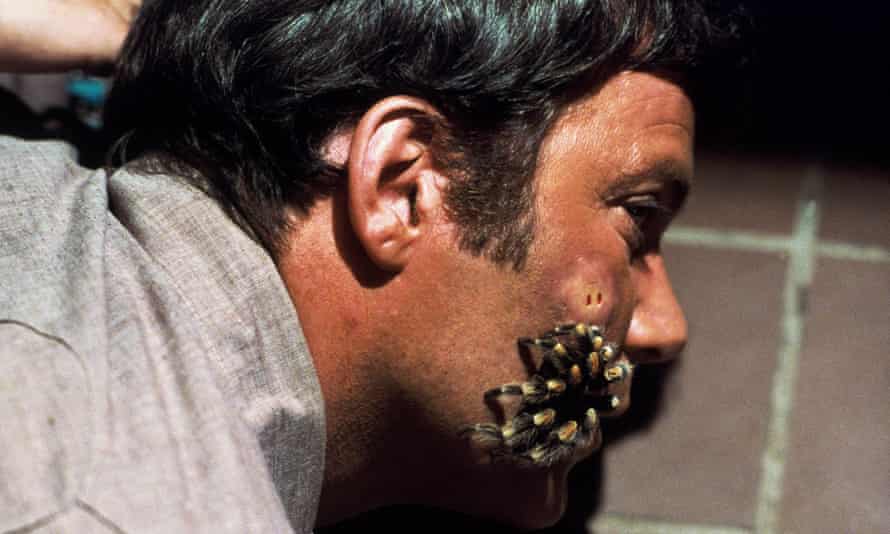

But I would contend that giant insects aren’t nearly as scary as normal-sized ones. The ants from Them! are too big to crawl into your ear, the way an ant once crawled into mine as I was gardening. (I sluiced it out with a wet cotton bud, but worried it might have laid eggs in my brain.) The gigantic Eight Legged Freaks in the film of the same name are nowhere near as creepy as the normal-sized spiders in Arachnophobia and the slow-but-deadly tarantulas that interrupt William Shatner’s attempts to chat up a comely arachnologist in Kingdom of the Spiders. Giant worms such as the ones in Dune, Beetlejuice and Tremors, and the bloodworm that slurps up Andy Serkis in King Kong are obviously best avoided, but for that extra-creepy skin-crawling factor they can’t hold a candle to the regular-sized annelids in Squirm, which ooze from showerheads and burrow into people’s faces.

William Shatner succumbs to a tarantula in Kingdom of the Spiders (1977).

Photograph: Dimension/Allstar

Insect eco-horror peaked in the 1970s with exploitation entrepreneurs such as William Castle, whose final production, Bugs (1975), features mutant cockroaches that set fire to people’s hair and spell out “WE LIVE” on the wall, and Irwin Allen, whose The Swarm proclaims patriotically: “The African killer bee portrayed in this film bears absolutely no resemblance to the industrious, hardworking American honey bee.” Damn migrant bees; coming over here and killing off beloved Hollywood veterans such as Olivia de Havilland and Henry Fonda!

But the insect threat is treated more seriously in the 1971 faux-documentary The Hellstrom Chronicle, which intersperses fascinating real footage of insect life with “Dr Nils Hellstrom” (played by an actor) predicting the rise of species such as the African driver ant, “a mindless unstoppable killing machine dedicated to the destruction of everything that stands in its way”. More alarming, albeit more obviously fictional, is the only feature directed by legendary credits designer Saul Bass: in his film Phase IV (1974), two scientists investigating unusual ant activity in the Arizona desert find themselves under siege when the colony’s hive mind fights back. Ants clearly appeal to the mindset of surrealistically inclined auteurs, pouring out of a hole in the palm of a hand in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou, crawling over a severed ear in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and – in Bass’s original ending to Phase IV, rejected by the studio for being too weird – taking over the world. Bow down to your insect overlords!

Insect eco-horror peaked in the 1970s with exploitation entrepreneurs such as William Castle, whose final production, Bugs (1975), features mutant cockroaches that set fire to people’s hair and spell out “WE LIVE” on the wall, and Irwin Allen, whose The Swarm proclaims patriotically: “The African killer bee portrayed in this film bears absolutely no resemblance to the industrious, hardworking American honey bee.” Damn migrant bees; coming over here and killing off beloved Hollywood veterans such as Olivia de Havilland and Henry Fonda!

But the insect threat is treated more seriously in the 1971 faux-documentary The Hellstrom Chronicle, which intersperses fascinating real footage of insect life with “Dr Nils Hellstrom” (played by an actor) predicting the rise of species such as the African driver ant, “a mindless unstoppable killing machine dedicated to the destruction of everything that stands in its way”. More alarming, albeit more obviously fictional, is the only feature directed by legendary credits designer Saul Bass: in his film Phase IV (1974), two scientists investigating unusual ant activity in the Arizona desert find themselves under siege when the colony’s hive mind fights back. Ants clearly appeal to the mindset of surrealistically inclined auteurs, pouring out of a hole in the palm of a hand in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou, crawling over a severed ear in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and – in Bass’s original ending to Phase IV, rejected by the studio for being too weird – taking over the world. Bow down to your insect overlords!

Olivia de Havilland as a schoolteacher attacked by killer bees in The Swarm (1977). Photograph: Warner Bros./Allstar

It’s possible that the “When Insects Attack” sub-genre has had its day, given recent developments on the ecological front. As Dr Hellstrom says: “In fighting the insect we have killed ourselves, polluted our water, poisoned our wildlife, permeated our own flesh with deadly toxins. The insect becomes immune, and we are poisoned. In fighting with superior intellect, we have outsmarted ourselves.” Even more troubling than the thought of being overrun by creepy-crawlies is the emerging information that, in the last two decades, three-quarters of the world’s insects have simply disappeared. This might be encouraging news for entomophobes, but it’s a terrible portent for the future of humanity, which has not only failed to acknowledge the importance of insects to the eco-system, but looks set to carry on trashing their natural habitats and spritzing them with ecologically unsound insecticides until every last one is gone.

The 20 greatest smackdown movies – ranked!

While recent eco-horror cinema has focused on climate change, film-makers still seem squeamish about insects; see Wounds, for example, or Mosquito State, or the 2020 French film The Swarm. Perhaps a few more adorable giant critters like Dominique wouldn’t go amiss, so we could start swapping our entomophobia for entomophilia, or we could put Godzilla on pause and start celebrating Mothra, a gentler, kinder sort of kaiju.

And perhaps we should emulate the 80% of the world’s population that regularly eats insects. Crickets, for example, are a rich source of protein and emit less than 0.1% of the greenhouse gases produced by cows. So let’s hope we’ve seen the last of dinner scenes like the one in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, in which the heroine turns up her nose at the crunchy beetles. It’s time now to adopt as a gourmet role model Renfield from Dracula (1931) who has no compunction about tucking into spiders and flies.

Mandibles is released in the UK on 17 September.

It’s possible that the “When Insects Attack” sub-genre has had its day, given recent developments on the ecological front. As Dr Hellstrom says: “In fighting the insect we have killed ourselves, polluted our water, poisoned our wildlife, permeated our own flesh with deadly toxins. The insect becomes immune, and we are poisoned. In fighting with superior intellect, we have outsmarted ourselves.” Even more troubling than the thought of being overrun by creepy-crawlies is the emerging information that, in the last two decades, three-quarters of the world’s insects have simply disappeared. This might be encouraging news for entomophobes, but it’s a terrible portent for the future of humanity, which has not only failed to acknowledge the importance of insects to the eco-system, but looks set to carry on trashing their natural habitats and spritzing them with ecologically unsound insecticides until every last one is gone.

The 20 greatest smackdown movies – ranked!

While recent eco-horror cinema has focused on climate change, film-makers still seem squeamish about insects; see Wounds, for example, or Mosquito State, or the 2020 French film The Swarm. Perhaps a few more adorable giant critters like Dominique wouldn’t go amiss, so we could start swapping our entomophobia for entomophilia, or we could put Godzilla on pause and start celebrating Mothra, a gentler, kinder sort of kaiju.

And perhaps we should emulate the 80% of the world’s population that regularly eats insects. Crickets, for example, are a rich source of protein and emit less than 0.1% of the greenhouse gases produced by cows. So let’s hope we’ve seen the last of dinner scenes like the one in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, in which the heroine turns up her nose at the crunchy beetles. It’s time now to adopt as a gourmet role model Renfield from Dracula (1931) who has no compunction about tucking into spiders and flies.

Mandibles is released in the UK on 17 September.

No comments:

Post a Comment