International

3 May 2023

Protesters hold placards that read “Journalism is not a crime” as they demand the release of a reporter facing charges under Bangladesh’s Digital Security Act (DSA), in Dhaka, 29 March 2023.

Syed Mahamudur Rahman/NurPhoto via Getty Images

RSF's 2023 World Press Freedom Index highlights disinformation as one of the biggest threats to journalism globally.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 3 May 2023.

The 21st edition of the World Press Freedom Index, compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), sheds light on major and often radical changes linked to political, social and technological upheavals.

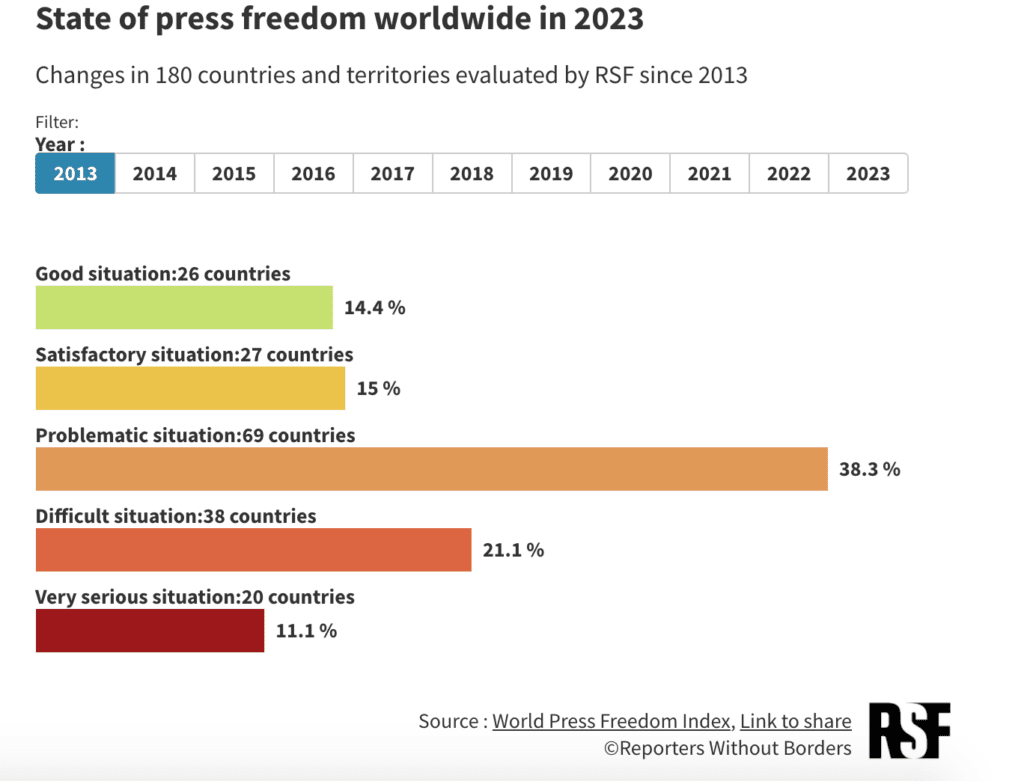

According to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries and territories and is published on World Press Freedom Day (3 May) – the situation is “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism is “bad” in seven out of ten countries, and satisfactory in only three out of ten.

Norway is ranked first for the seventh year running. But – unusually – a non-Nordic country is ranked second, namely Ireland (up 4 places at 2nd), ahead of Denmark (down 1 place at 3rd). The Netherlands (6th) has risen 22 places, recovering the position it had in 2021, before crime reporter Peter R. de Vries was murdered.

There are changes at the bottom of the Index, too. The last three places are occupied solely by Asian countries: Vietnam (178th), which has almost completed its hunt of independent reporters and commentators; China (down 4 at 179th), the world’s biggest jailer of journalists and one of the biggest exporters of propaganda content; and, to no great surprise, North Korea (180th).

RSF's 2023 World Press Freedom Index highlights disinformation as one of the biggest threats to journalism globally.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 3 May 2023.

The 21st edition of the World Press Freedom Index, compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), sheds light on major and often radical changes linked to political, social and technological upheavals.

According to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries and territories and is published on World Press Freedom Day (3 May) – the situation is “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism is “bad” in seven out of ten countries, and satisfactory in only three out of ten.

Norway is ranked first for the seventh year running. But – unusually – a non-Nordic country is ranked second, namely Ireland (up 4 places at 2nd), ahead of Denmark (down 1 place at 3rd). The Netherlands (6th) has risen 22 places, recovering the position it had in 2021, before crime reporter Peter R. de Vries was murdered.

There are changes at the bottom of the Index, too. The last three places are occupied solely by Asian countries: Vietnam (178th), which has almost completed its hunt of independent reporters and commentators; China (down 4 at 179th), the world’s biggest jailer of journalists and one of the biggest exporters of propaganda content; and, to no great surprise, North Korea (180th).

“The World Press Freedom Index shows enormous volatility in situations, with major rises and falls and unprecedented changes, such as Brazil’s 18-place rise and Senegal’s 31-place fall. This instability is the result of increased aggressiveness on the part of the authorities in many countries and growing animosity towards journalists on social media and in the physical world. The volatility is also the consequence of growth in the fake content industry, which produces and distributes disinformation and provides the tools for manufacturing it.”Christophe Deloire, RSF Secretary-General

Effects of the fake content industry

The 2023 Index spotlights the rapid effects that the digital ecosystem’s fake content industry has had on press freedom. In 118 countries (two-thirds of the 180 countries evaluated by the Index), most of the Index questionnaire’s respondents reported that political actors in their countries were often or systematically involved in massive disinformation or propaganda campaigns. The difference is being blurred between true and false, real and artificial, facts and artifices, jeopardising the right to information. The unprecedented ability to tamper with content is being used to undermine those who embody quality journalism and weaken journalism itself.

The remarkable development of artificial intelligence is wreaking further havoc on the media world, which had already been undermined by Web 2.0. Meanwhile, Twitter owner Elon Musk is pushing an arbitrary, payment-based approach to information to the extreme, showing that platforms are quicksand for journalism.

The disinformation industry disseminates manipulative content on a huge scale, as shown by an investigation by the Forbidden Stories consortium, a project co-founded by RSF. And now AI is digesting content and regurgitating it in the form of syntheses that flout the principles of rigour and reliability.

The fifth version of Midjourney, an AI programme that generates very high-definition images in response to natural language requests, has been feeding social media with increasingly plausible and undetectable fake “photos”, including quite realistic-looking ones of Donald Trump being stopped by police officers and a comatose Julian Assange in a straitjacket, which went viral.

Propaganda war

The terrain has been favourable for an increase in propaganda by Russia(164th), which has fallen another nine places in the 2023 Index. In record time, Moscow has established a new media arsenal dedicated to spreading the Kremlin’s message in the occupied territories in southern Ukraine, while cracking down harder than ever on the last remaining independent Russian media outlets, which have been banned, blocked and/or declared “foreign agents”. Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine (79th) helped give this country one of the Index’s worst scores for security.

Rises and falls

The United States (45th) has fallen three places. The Index questionnaire’s US respondents were negative about the environment for journalists (especially the legal framework at the local level, and widespread violence) despite the Biden administration’s efforts. The murders of two journalists (the Las Vegas Review Journal’s Jeff German in September 2022, and Spectrum News 13’s Dylan Lyons in February 2023) had a negative impact on the country’s ranking. Brazil (92nd) rose 18 places as result of the departure of Jair Bolsonaro, whose presidential term was marked by extreme hostility towards journalists, and Lula da Silva’s election, heralding an improvement. In Asia, changes in governments also improved the environment for the media and accounted for such significant rises in the Index as Australia’s (up 12 at 27th) and Malaysia’s (up 40 at 73rd).

The situation has gone from “problematic” to “very bad” in three other countries: Tajikistan (down 1 at 153rd), India (down 11 at 161st) and Turkey (down 16 at 165th). In India, media takeovers by oligarchs close to Prime Minister Modi have jeopardised pluralism, while the Erdogan administration in Turkey has stepped up its persecution of journalists in the run-up to elections scheduled for 14 May. In Iran (177th), the heavy-handed crackdown on the protests triggered by the young student Mahsa Amini’s death in police custody drove the country’s “social context” and “judicial environment” scores even lower.

Some of the 2023 Index’s biggest falls have been in Africa. Until recently a regional model, Senegal (104th) has fallen 31 places, above all because of the criminal charges brought against two journalists, Pape Alé Niang and Pape Ndiaye, and the sharp decline in security for media personnel. In the Maghreb, Tunisia (121st) has fallen 27 places as a result of President Kais Saied’s growing authoritarianism and inability to tolerate media criticism. In Latin America, Peru (110th) has plummeted 33 places because its journalists are paying dearly for the persistent political instability and are being harassed, attacked and smeared because of their proximity to leading politicians. The fall by Haiti (down 29 at 99th) is also due mainly to the continuing decline in the security environment.

The Index by region

Europe, especially the European Union, is the region of the world where it is easiest for journalists to work, but the situation is mixed even there. Germany (21st), where a record number of cases of violence against journalists and arrests have been recorded, has fallen five places. Poland (57th), where 2022 was relatively calm from a press freedom viewpoint, has risen nine places, while France (24th) has risen two. Greece (107th), where journalists were spied on by the intelligence services and by powerful spyware, continues to have the EU’s lowest ranking. The Europe-Central Asia regional score is also heavily impacted by Central Asia’s poor results. Several of its countries – Kyrgyzstan (down 50 at 122nd), Kazakhstan (down 12 at 134th) and Uzbekistan (down 4 at 137th) – have fallen because of increases in the number of attacks against media. Finally, Turkmenistan (176th), where censorship and surveillance were stepped up yet again after Serdar Berdimuhamedow, the outgoing president’s son, was elected president in March 2022, is still one of the Index’s bottom five countries.

America no longer has any country coloured green on the press freedom map. Costa Rica (down 15 at 23rd) was the last country in the region to have a situation classified as “good”, but its classification has changed following a five-place fall due to a sharp decline in its political score (down 15.68 points), and it is now ranked lower than Canada (up 4 at 15th). Mexico (128th) has fallen another place this year and now has the world’s most disappeared journalists (28 in the past 20 years). Cuba (172nd), where censorship has been stepped up again and where the press is still a state monopoly, continues to have the region’s lowest ranking, as it did in 2022.

Even if Africa has seen a few significant rises, such as that of Botswana (65th), which has risen 35 places, journalism overall has become more difficult in this continent and the situation is now classified as “bad” in nearly 40% of its countries (against 33% in 2022). They include Burkina Faso (58th), where local retransmission of international broadcasters has been banned and journalists have been deported, and the Sahel in general, which is in the process of becoming a “no-news zone”. Several journalists have also been murdered in Africa, including Martinez Zongo in Cameroon (138th). In Eritrea (174th), the media remain in President Issaias Afwerki’s despotic grip.

The Asia-Pacific continues to have some of the world’s worst regimes for journalists. Myanmar (173rd), the world’s second biggest jailer of journalists since the military coup in February 2021, and Afghanistan (152nd), where the environment for reporters continues to worsen and women journalists have been literally erased from public life, are still at the tail end of the Index.

Last in the regional ranking, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) continues to be the world’s most dangerous region for journalists, with a situation classified as “very bad” in more than half of its countries. The very low score of some countries, including Syria (175th), Yemen (168th) and Iraq (167th), is due in particular to the large number of journalists who are missing or held hostage. Although Palestine (156th) has risen 14 places, its security indicator is very low after two more journalists were killed in 2022. Saudi Arabia remains rooted near the bottom of the Index. In the Maghreb, media owner Ihsane El Kadi’s imprisonment has confirmed the growing authoritarianism in Algeria (136th), which has fallen two places and where the situation continues to be classified as “bad”.

No comments:

Post a Comment