Opinion by Michael Coren • CNN

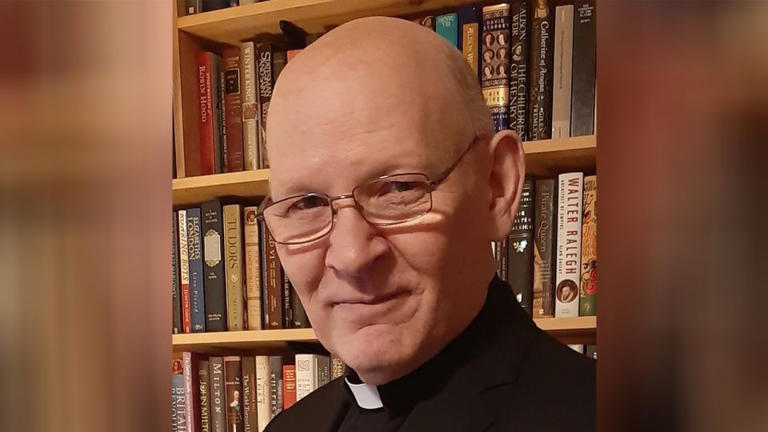

Editor’s Note: Father Michael Coren is an Anglican priest, journalist and writer. He is a columnist for the Toronto Star, frequent contributor to the Globe and Mail and the author of 18 books. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

I don’t think I was ever a homophobe, but I certainly came close.

Michael Coren - Courtesy Rev Michael Coren© Provided by CNN

That is a profoundly shocking thought, and extremely painful for me to say, especially as, for the past decade, I’ve been regarded in Canada as a Christian champion of equal marriage, same-sex blessings and the full affirmation of LGBTQ+ people in the church. The change, the transformation, the conversion – for that is what it was – came about for various reasons, but mostly because of a new reading and understanding of the Bible.

I became an ally because of a deeper faith. Here I now had to stand. I could do no other.

Some background and context: Until 2013 I was a Roman Catholic, and as a journalist and broadcaster with a fairly high profile, spoke and wrote frequently in support of Catholic sexual teachings. There are, of course, many Catholics who dissent from the official line, but the official line it remains. And according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered” and “contrary to the natural law.” Pope Francis has made some soothing and compromising comments but, at heart, very little has changed. In January 2023, Pope Francis told The Associated Press that “being homosexual is not a crime,” yet then reiterated that homosexuality was “a sin” under Catholic doctrine. And while he encouraged bishops to welcome gay people into their ministries “with tenderness,” he also discredited larger attempts to alter existing church practices, which included attempts to provide church blessings to same-sex couples.

I suppose I could have tried to find a way to ignore this, but life’s messy realities do find a way. In March 2014, the humanitarian organization World Vision US announced that it would hire Christians in same-sex marriages in its US offices. The organization’s motives were entirely noble, if a little naïve. Within two days, numerous leading evangelical groups denounced the charity, threatening to withdraw support. World Vision apologized, reversed its new policy and asked for forgiveness. It seemed such a cruel over-reaction, such a humiliation of good people.

At around the same time, Canada’s then-foreign minister John Baird criticized the Ugandan president for legislation that could lead to life imprisonment for gay sex. I supported Baird on my television show, arguing that even those of us who disagreed with same-sex marriage surely condemned such a monstrous policy. As a result, I was roundly attacked by Christian conservatives, Catholic as well as Protestant.

I felt as if I were being pushed against a wall of uncertainty. My defense of traditional Christian teachings on the issue was, I’d always assumed, based on love rather than hate. I started to question myself. Was that a self-defense mechanism, a comforting denial of truth? Perhaps. And that creeping doubt led me to return to scripture. “Tolle Lege,” said that mysterious voice to St. Augustine. Take up and read. So, I did.

The Bible can be as gentle as a watercolor and as powerful as a thunderstorm. It can be taken literally or taken seriously but not always both. It’s a library written over centuries, containing poetry and metaphor as well as history and biography, and without discernment, it makes little sense. It has to be, must be, read through the prism of empathy and the human condition.

The thing is, the Bible hardly mentions homosexuality, which is of course a word not coined until the late 19th-century. The so-called “gotcha” verses from the Old Testament are specific to ancient customs and are often misunderstood. The Sodom story, for example, wasn’t interpreted as referring to homosexuality until the 11th-century. Lot – the hero of the text – offers his virgin daughters to the mob in place of his guests, so it can’t exactly be used as a compelling morality tale!

Ezekiel in the Hebrew Scriptures says, “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy. They were haughty, and did abominable things before me” (Ezekiel 16:49-50).

The Old Testament never speaks of lesbianism, and its mentions of sex are more about procreation and the preservation of the tribe than personal morality and romance. It also has some rather disturbing things to say about slavery in Genesis and in Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, about ethnic cleansing in Deuteronomy and even killing children in First Samuel. So a precise guide to modern manners it’s certainly not.

Jesus doesn’t mention the issue, and St. Paul’s comments, mainly in his letters to the Romans, are more about men using young male prostitutes in pagan initiation rites than about loving, consenting same-sex relationships. There is, however, one possible discussion in the New Testament. It’s when Jesus is approached by a centurion whose beloved male servant is dying. Will Jesus cure him? Of course, and Jesus then praises the Roman for his faith. The Greek word used to describe the relationship between the Roman and his “beloved” servant indicates something far deeper than mere platonic affection.

Then there’s the love of David and Jonathan, Jesus refusing to judge and the pristine beauty of grace and justice that informs the Gospels. Most of all, there’s the permanent revolution of love that Jesus didn’t request but demand. His central teaching, remember, is to love God and love our neighbors as ourselves. We’re told this in three of the four Gospels — Matthew (22:35-40), Mark (12:28-34) and Luke (10:27). It’s a transformational moment for Christians, to know that only by loving others can we properly know and love God.

As I read more, I prayed more. As I prayed more, I reached out to gay Christians, who taught me lessons in forgiveness that shamed me. I made a public apology in my syndicated newspaper column for harm caused to the LGBTQ+ community by my writing and broadcasting. As a consequence, I felt the full force of those on the political and religious right. I’ve reported from Northern Ireland and the Middle East but seldom seen such visceral hatred. Abuse, threats, attacks on my children and campaigns to have me canceled and fired. Thank God, because it confirmed everything that I’d come to believe.

I became an Anglican, and three years later entered seminary. I’m now a priest, spend my time trying to preach the genuine song of the Gospels, and write books and columns doing the same. In other words, I’m a Christian conservative’s nightmare. But for me, a dream lived. I found truth. I found Jesus. This straight, 64-year-old man, married for 36 years and with four children, has a lot to be grateful for. Most of all, I thank the gay community for teaching me so much about what Christianity really means.

Editor’s Note: Father Michael Coren is an Anglican priest, journalist and writer. He is a columnist for the Toronto Star, frequent contributor to the Globe and Mail and the author of 18 books. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

I don’t think I was ever a homophobe, but I certainly came close.

Michael Coren - Courtesy Rev Michael Coren© Provided by CNN

That is a profoundly shocking thought, and extremely painful for me to say, especially as, for the past decade, I’ve been regarded in Canada as a Christian champion of equal marriage, same-sex blessings and the full affirmation of LGBTQ+ people in the church. The change, the transformation, the conversion – for that is what it was – came about for various reasons, but mostly because of a new reading and understanding of the Bible.

I became an ally because of a deeper faith. Here I now had to stand. I could do no other.

Some background and context: Until 2013 I was a Roman Catholic, and as a journalist and broadcaster with a fairly high profile, spoke and wrote frequently in support of Catholic sexual teachings. There are, of course, many Catholics who dissent from the official line, but the official line it remains. And according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered” and “contrary to the natural law.” Pope Francis has made some soothing and compromising comments but, at heart, very little has changed. In January 2023, Pope Francis told The Associated Press that “being homosexual is not a crime,” yet then reiterated that homosexuality was “a sin” under Catholic doctrine. And while he encouraged bishops to welcome gay people into their ministries “with tenderness,” he also discredited larger attempts to alter existing church practices, which included attempts to provide church blessings to same-sex couples.

I suppose I could have tried to find a way to ignore this, but life’s messy realities do find a way. In March 2014, the humanitarian organization World Vision US announced that it would hire Christians in same-sex marriages in its US offices. The organization’s motives were entirely noble, if a little naïve. Within two days, numerous leading evangelical groups denounced the charity, threatening to withdraw support. World Vision apologized, reversed its new policy and asked for forgiveness. It seemed such a cruel over-reaction, such a humiliation of good people.

At around the same time, Canada’s then-foreign minister John Baird criticized the Ugandan president for legislation that could lead to life imprisonment for gay sex. I supported Baird on my television show, arguing that even those of us who disagreed with same-sex marriage surely condemned such a monstrous policy. As a result, I was roundly attacked by Christian conservatives, Catholic as well as Protestant.

I felt as if I were being pushed against a wall of uncertainty. My defense of traditional Christian teachings on the issue was, I’d always assumed, based on love rather than hate. I started to question myself. Was that a self-defense mechanism, a comforting denial of truth? Perhaps. And that creeping doubt led me to return to scripture. “Tolle Lege,” said that mysterious voice to St. Augustine. Take up and read. So, I did.

The Bible can be as gentle as a watercolor and as powerful as a thunderstorm. It can be taken literally or taken seriously but not always both. It’s a library written over centuries, containing poetry and metaphor as well as history and biography, and without discernment, it makes little sense. It has to be, must be, read through the prism of empathy and the human condition.

The thing is, the Bible hardly mentions homosexuality, which is of course a word not coined until the late 19th-century. The so-called “gotcha” verses from the Old Testament are specific to ancient customs and are often misunderstood. The Sodom story, for example, wasn’t interpreted as referring to homosexuality until the 11th-century. Lot – the hero of the text – offers his virgin daughters to the mob in place of his guests, so it can’t exactly be used as a compelling morality tale!

Ezekiel in the Hebrew Scriptures says, “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy. They were haughty, and did abominable things before me” (Ezekiel 16:49-50).

The Old Testament never speaks of lesbianism, and its mentions of sex are more about procreation and the preservation of the tribe than personal morality and romance. It also has some rather disturbing things to say about slavery in Genesis and in Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, about ethnic cleansing in Deuteronomy and even killing children in First Samuel. So a precise guide to modern manners it’s certainly not.

Jesus doesn’t mention the issue, and St. Paul’s comments, mainly in his letters to the Romans, are more about men using young male prostitutes in pagan initiation rites than about loving, consenting same-sex relationships. There is, however, one possible discussion in the New Testament. It’s when Jesus is approached by a centurion whose beloved male servant is dying. Will Jesus cure him? Of course, and Jesus then praises the Roman for his faith. The Greek word used to describe the relationship between the Roman and his “beloved” servant indicates something far deeper than mere platonic affection.

Then there’s the love of David and Jonathan, Jesus refusing to judge and the pristine beauty of grace and justice that informs the Gospels. Most of all, there’s the permanent revolution of love that Jesus didn’t request but demand. His central teaching, remember, is to love God and love our neighbors as ourselves. We’re told this in three of the four Gospels — Matthew (22:35-40), Mark (12:28-34) and Luke (10:27). It’s a transformational moment for Christians, to know that only by loving others can we properly know and love God.

As I read more, I prayed more. As I prayed more, I reached out to gay Christians, who taught me lessons in forgiveness that shamed me. I made a public apology in my syndicated newspaper column for harm caused to the LGBTQ+ community by my writing and broadcasting. As a consequence, I felt the full force of those on the political and religious right. I’ve reported from Northern Ireland and the Middle East but seldom seen such visceral hatred. Abuse, threats, attacks on my children and campaigns to have me canceled and fired. Thank God, because it confirmed everything that I’d come to believe.

I became an Anglican, and three years later entered seminary. I’m now a priest, spend my time trying to preach the genuine song of the Gospels, and write books and columns doing the same. In other words, I’m a Christian conservative’s nightmare. But for me, a dream lived. I found truth. I found Jesus. This straight, 64-year-old man, married for 36 years and with four children, has a lot to be grateful for. Most of all, I thank the gay community for teaching me so much about what Christianity really means.

No comments:

Post a Comment