SPACE/COSMOS

International Space Station crew to return early after astronaut medical issue

By AFP

January 8, 2026

Crew-11 mission astronauts departed the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida on August 1, 2025 - Copyright AFP Gregg Newton

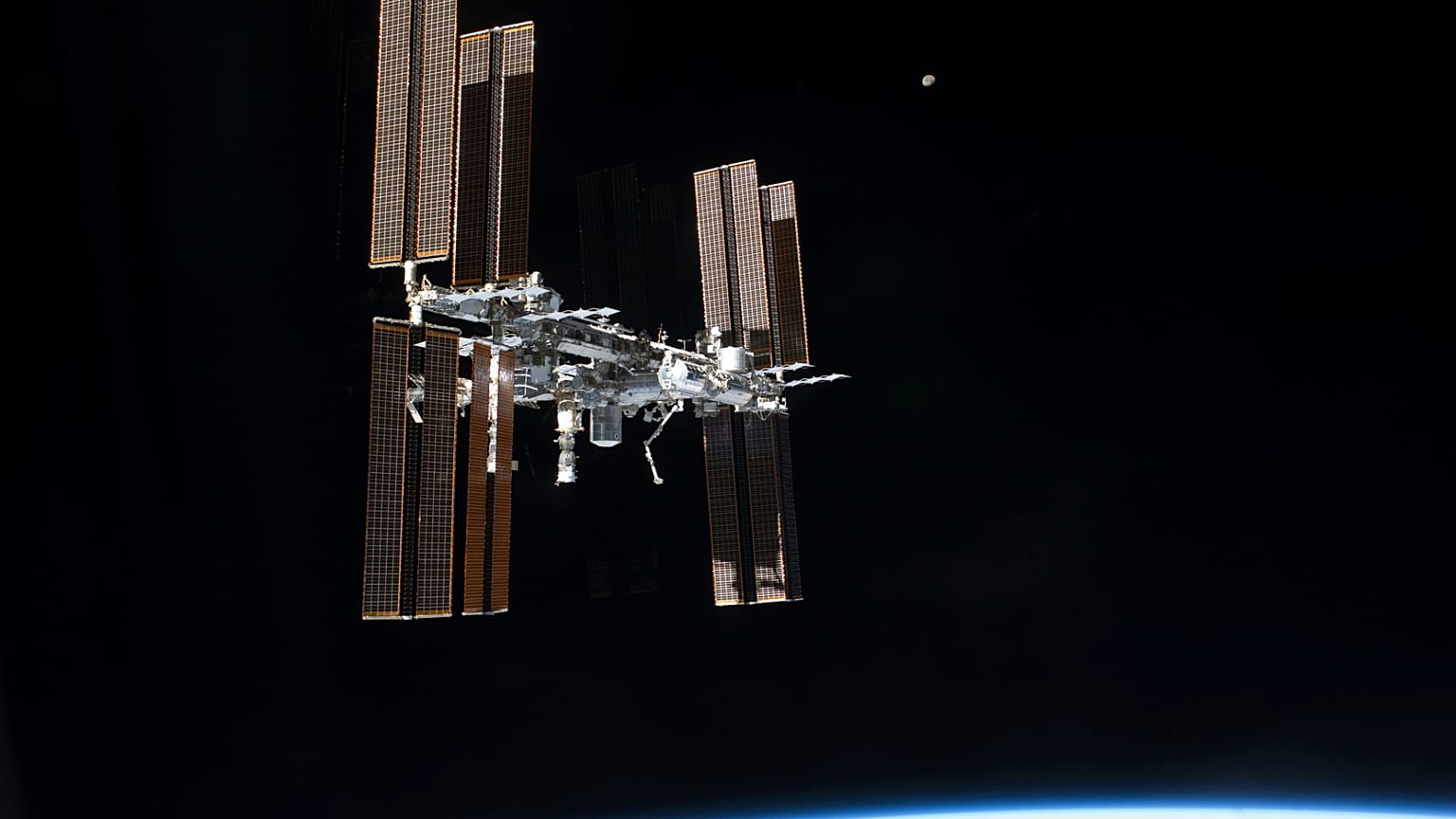

NASA crewmembers at the International Space Station will return to Earth within days after an astronaut suffered a health issue, the US space agency said Thursday, the first such medical evacuation in the orbital lab’s history.

Officials did not provide details of the medical event but said the unidentified crewmember is stable. They said it did not result from any kind of injury onboard or from ISS operations.

NASA chief medical officer James Polk said “lingering risk” and a “lingering question as to what that diagnosis is” led to the decision to return early. Officials insisted it was not an emergency evacuation.

The four astronauts on NASA-SpaceX Crew 11 — US members Mike Fincke and Zena Cardman along with Japan’s Kimiya Yui and Russia’s Oleg Platonov — would return within the coming days to one of the routine splashdown sites.

Amit Kshatriya, a NASA associate administrator, said it was the “first time we’ve done a controlled medical evacuation from the vehicle. So that is unusual.”

He said the crew deployed their “onboarding training” to “manage unexpected medical situations.”

“Yesterday was a textbook example of that training in action. Once the situation on the station stabilized, careful deliberations led us to the decision to return Crew 11… while ensuring minimal operational impact to ongoing work aboard.”

– ‘Trained professionals’ –

The four astronauts set to return have been on their mission since August 1. Such journeys generally last approximately six months, and this crew was already due to return in the coming weeks.

Officials indicated it was possible the next US mission could depart to the ISS earlier than scheduled, but did not provide specifics.

Chris Williams, who launched on a Russian mission to the station, will stay onboard to maintain US presence.

Russians Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergei Mikaev are also there.

NASA had previously said it was postponing a spacewalk planned for Thursday due to the medical issue.

Astronauts Fincke and Cardman were to carry out the approximately 6.5-hour spacewalk to perform power upgrade work.

Continuously inhabited since 2000, the ISS functions as a testbed for research that supports deeper space exploration — including eventual missions to Mars.

The ISS is set to be decommissioned after 2030, with its orbit gradually lowered until it breaks up in the atmosphere over a remote part of the Pacific Ocean called Point Nemo, a spacecraft graveyard.

New Census Of Sun’s Neighbors Reveals Best Potential Real Estate For Life

Artist’s concept of a planet orbiting in the habitable zone of a K star. CREDIT Courtesy: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/Tim Pyle

January 7, 2026

By Eurasia Review

A new study led by a Georgia State University astronomy graduate student is a major step forward in the search for stars that could host Earth-like planets that may prove to be good havens for life to develop. Sebastián Carrazco-Gaxiola shared the results at the January 2026 meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, Ariz.

“This survey marks the first comprehensive look at thousands of the Sun’s lower-mass cousins,” Carrazco-Gaxiola said. “These stars, known as ‘K dwarfs,’ are commonly found throughout space, and they provide a long-term, stable environment for their planetary companions.”

Carrazco-Gaxiola’s survey focuses on over 2,000 stars that are closer than 130 light-years from Earth. The observations are precise measurements of the spectra, or rainbow of colors, emitted by these stars.

The observations were made with state-of-the-art spectrographs on the SMARTS 60-inch mirror telescope at the Cerro Tololo Interamerican Observatory in the Chilean Andes and on the same-sized Tillinghast Telescope at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in southern Arizona. Together, these two telescopes located in opposite hemispheres allow observations of K-dwarfs across the full sky.

“The CHIRON spectrograph on the SMARTS telescope in Chile and the TRES spectrograph on the Tillinghast Telescope in Arizona are such complementary instruments,” said Allyson Bieryla, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. “The power of having these two telescopes in opposite hemispheres is that it gives us access to all the K-dwarfs across the entire sky.”

Stars come in a wide range of temperatures and masses, and the K dwarf group is slightly cooler and fainter than the Sun. But there are about two times as many K dwarfs compared to Sun-like stars in the “solar neighborhood,” our region in space. They also have much longer lives than Sun-like stars. Any life forms emerging on planets around K dwarfs will enjoy sustaining star-shine almost indefinitely.

Careful analysis of the measurements provides astronomers with estimates of the stars’ temperature, age, spin rate and space motion. In addition, certain colors probe the existence of heated upper layers in the star that are energized by stellar magnetic fields. All of these factors are critical to the environments experienced by planets orbiting the stars.

“This survey will be the foundation for studies of nearby stars for decades to come,” said Distinguished University Professor of Physics and Astronomy Todd Henry, who serves as Carrazco-Gaxiola’s adviser and is a senior author on the study. “These stars and their planets will be the destinations for spacecraft exploration in the far future of space travel.”

Dark Stars Could Help Solve Three Pressing Puzzles Of The High-Redshift Universe

UHZ1, a record breaking galaxy 13.2 billion light-years away, seen when the universe was only 3% of its current age. UHZ1 is puzzling in view of it harboring a supermassive black hole that could not have possibly been seeded even by regular stars, in view of its mass and very little time for the BH to grow. As such, UHZ1 is believed to be evidence for supermassive stars that, upon collapse, generate the supermassive black hole powering the quasar at its center. In this study, the authors show how UHZ1 could harbor a supermassive black hole seeded by the collapse of a dark star. The mechanisms identified by the authors are not restricted to UHZ1 — it provides a pathway for explaining over massive black hole galaxies, of which UHZ1 is a prominent example. CREDIT X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/Ákos Bogdán; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare & K. Arcand

January 9, 2026

By Eurasia Review

A recent study led by Colgate Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy Cosmin Ilie, in collaboration with Jillian Paulin ’23 at the University of Pennsylvania, Andreea Petric of the Space Telescope Science Institute, and Katherine Freese of the University of Texas at Austin, provides answers to three seemingly disparate, yet pressing, cosmic dawn puzzles. Specifically, the authors show how dark stars could help explain the unexpected discovery of “blue monster” galaxies, the numerous early overmassive black hole galaxies, and the “little red dots” in images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The first stars in the universe form in dark matter–rich environments, at the centers of dark matter microhalos. Roughly a few hundred million light-years after the Big Bang, molecular clouds of hydrogen and helium cooled sufficiently well to begin a process of gravitational collapse, which eventually led to the formation of the first stars. This phenomenon marked the beginning of the cosmic dawn era, a period offering the right conditions for the formation of stars powered by dark matter annihilations, also known as dark stars. Those objects can grow to become supermassive, and are natural seeds for supermassive black holes.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observed the most distant objects yet to be studied, and those discoveries pose significant challenges to standard models of the formation of the first stars and galaxies. Specifically, a large fraction of the most distant galaxies are now categorized as “blue monsters,” i.e., extremely bright, yet ultra-compact and almost devoid of dust. The existence of such galaxies was extremely unexpected, as no pre-JWST era simulations or theoretical models of the formation of the first galaxies predicted their existence.

Moreover, the JWST data further exacerbate the problem of the seeds for larger-than-expected supermassive black holes (SMBHs) powering the most distant quasars ever observed. Lastly, JWST has observed a whole new class of objects, including “little red dots” (LRDs), which are very compact, dustless cosmic dawn sources which unexpectedly emit little to no X-ray radiation.

Those three puzzles, combined, indicate that the commonly accepted pre-JWST models for the formation of the first galaxies and first supermassive black holes require significant refinements.

“Some of the most significant mysteries posed by the JWST’s cosmic dawn data are in fact features of the dark star theory,” Ilie said.

While dark stars are yet to be confirmed experimentally, this recent publication adds a significant piece to the existing evidence: photometric and spectroscopic candidates, which were discovered in two separate PNAS studies published in 2023 and 2025, respectively. In addition to discussing in-depth mechanisms via which dark stars could provide solutions to the mysteries posed by the blue monsters, little red dots, and overmassive black hole galaxies, this work also presents the most up-to-date spectroscopic analysis, finding evidence for dark star smoking-gun absorption features due to helium in the spectra of JADES-GS-13-0, in addition to the one previously found for JADES-GS-14-0.

Dark stars are some of the most exciting astrophysical objects to possibly exist, as their study would allow for a determination of the physical properties of the dark matter particle, and thus complement the vast experimental efforts for the detection of dark matter in laboratories on Earth, via direct detection or particle production.

New images capture rare interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS passing through our Solar System

The comet, discovered in July 2025, originated far beyond our Solar System and is thought to be around 7 billion years old - even older than the Sun.

Two stunning new images of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS - one captured from Earth by the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, and another taken from deep space by NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft - have been released to the world.

The comet made global headlines in 2025 when astronomers confirmed it was passing through our Solar System after forming around a distant star.

It is thought to be the oldest comet ever observed - and one of only three interstellar objects ever discovered in our Solar System.

The first image was taken on November 26, 2025 using the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph on the Gemini North telescope, which sits atop Maunakea - a dormant volcano on the Pacific island of Hawaii.

Because comets move quickly across the sky compared with background stars, the telescope had to track the comet’s motion during long exposures. This causes stars in the background to appear as streaks. The final image has since been processed to correct for this effect, keeping the stars fixed in place.

NASA has also released an image of 3I/ATLAS captured by the Europa Clipper spacecraft, which launched in October 2024 and is currently travelling to Jupiter.

Europa Clipper’s primary mission is to study Europa, one of Jupiter’s largest moons.

Although the spacecraft will not reach the Jupiter system until 2030, its instruments are already active, allowing it to observe and capture passing objects.

NASA scientists used this opportunity to turn Europa Clipper’s camera towards 3I/ATLAS, capturing this unique view of the comet from space as it passed through the inner Solar System.

Combining multiple wavelengths of UV light, the image shows the coma of gas (blue and green) and dust (red) that surrounds the comet’s nucleus.

Europa Clipper observed 3I/ATLAS on for a period of about seven hours, from a distance of around 164 million kilometres.

A rare visitor from beyond our Solar System

Comet 3I/ATLAS was discovered on July 1, 2025 and quickly became one of the biggest space science stories of the year.

Unlike most comets, which form within our own Solar System, 3I/ATLAS originated far beyond it.

As only the third confirmed interstellar object ever recorded - after ʻOumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019 - 3I/ATLAS sparked attention for its icy core enveloped by a coma, the luminous halo of gas and dust.

Since its discovery, scientists have been racing to observe the comet using some of humanity’s most powerful telescopes, before it exits the Solar System and disappears from view forever.

The comet also sparked speculation about a potentially more mysterious origin. Observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) showed it veered slightly -four arcseconds off its predicted path - and its colour shifted dramatically, from reddish to deep blue.

In a blog post, Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb suggested the anomaly might even indicate "the technological signature of an internal engine," though most scientists cautioned that natural explanations were far more likely.

As of now, no concrete evidence has supported the theory that 3I/ATLAS was sent by aliens. On the contrary, recent efforts to find markers of extraterrestrial technology on 3I/ATLAS came up empty.

On December 18, a day before 3I/ATLAS reached its closest point to earth, astronomers used the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to search the comet for "technosignatures," or measurable signs of alien technology. But the world's largest fully steerable radio telescope could not find anything of note.

For now, 3I/ATLAS continues its brief, spectacular journey through our cosmic neighbourhood. According to NASA, its final significant encounter will be its close flyby of Jupiter in March 2026, before leaving our solar system for good.

NASA shortens space station mission due to an astronaut's medical issue in a rare move

The space agency pulled four astronauts from the International Space Station due to a 'serious medical condition' affecting one of the crew. It did not identify the astronaut or the medical issue, citing patient privacy.

In a rare move, NASA is cutting a mission aboard the International Space Station short after an astronaut had a medical issue.

The space agency said Thursday the United States-Japanese-Russian crew of four will return to Earth in the coming days, earlier than planned.

NASA cancelled its first spacewalk of the year because of the health issue. The space agency did not identify the astronaut or the medical issue, citing patient privacy. The crew member is now stable.

NASA officials stressed that it was not an onboard emergency, but are "erring on the side of caution for the crew member,” said Dr James Polk, NASA's chief health and medical officer.

Polk said this was NASA’s first medical evacuation from the space station, although astronauts have been treated aboard for things like toothaches and ear pain

The crew of four returning home arrived at the orbiting lab via SpaceX in Augustfor a stay of at least six months. The crew included NASA’s Zena Cardman and Mike Fincke, along with Japan’s Kimiya Yui and Russia’s Oleg Platonov.

Fincke and Cardman were supposed to carry out the spacewalk to make preparations for a future rollout of solar panels to provide additional power for the space station.

It was Fincke’s fourth visit to the space station and Yui's second, according to NASA. This was the first spaceflight for Cardman and Platonov.

“I’m proud of the swift effort across the agency thus far to ensure the safety of our astronauts,” NASA administrator Jared Isaacman said.

Three other astronauts are currently living and working aboard the space station, including NASA’s Chris Williams and Russia’s Sergei Mikaev and Sergei Kud-Sverchkov, who launched in November aboard a Soyuz rocket for an eight-month stay. They’re due to return home in the summer.

NASA has tapped SpaceX to eventually bring the space station out of orbit by late 2030 or early 2031. Plans called for a safe re-entry over ocean.

Astronomers find missing link to galaxy's most common planets

National Institutes of Natural Sciences

image:

Artist’s impression of four orbiting exoplanets. Intense radiation from the host star may be heating their puffy atmospheres, causing atmospheric escape into space. (Credit: Astrobiology Center)

view moreCredit: Astrobiology Center

–

January 7, 2026 (London time) – One of the biggest recent surprises in astronomy is the discovery that most stars like the Sun harbor a planet between the size of Earth and Neptune within the orbit of Mercury — sizes and orbits absent from our solar system. These ‘super-Earths and sub-Neptunes’ are the galaxy's most common planets, but their formation has been shrouded in mystery. Now, an international team of astronomers has found a crucial missing link. By weighing four newborn planets in the V1298 Tau system, they've captured a rare snapshot of worlds in the process of transforming into the galaxy's most common planetary types.

“What's so exciting is that we're seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system," says John Livingston, the study's lead author from the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo, Japan. "The four planets we studied will likely contract into 'super-Earths' and 'sub-Neptunes'—the most common types of planets in our galaxy, but we've never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.”

The study focused on V1298 Tau, a star only about 20 million years old—a blink of an eye in cosmic time compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old Sun. Orbiting this young, active star are four giant planets, all between the sizes of Neptune and Jupiter, caught in a fleeting and turbulent phase of rapid evolution. This system appears to be a direct ancestor of the compact, multi-planet systems found throughout the galaxy. Like the Rosetta Stone that helped scholars decipher Egyptian hieroglyphics, V1298 Tau helps us decode how the galaxy's most common planets came to be.

For a decade, the team used an arsenal of ground- and space-based telescopes to precisely measure when each planet passed in front of the star, an event known as a transit. By timing these transits, astronomers detected that the planets' orbits were not perfectly regular. Their orbital configuration and gravity cause them to tug on each other, slightly speeding up or slowing down their celestial dance. These tiny shifts in timing, called Transit-Timing Variations (TTVs), allowed the team to robustly measure the planets' masses for the first time.

“For astronomers, our go-to ‘Doppler’ method for weighing planets involves making careful measurements of the star’s velocity as it’s tugged by its retinue of planets.” said Erik Petigura, a co-author from UCLA. "But young stars are so extremely spotty, active, and temperamental, that the Doppler method is a non-starter.” By using TTVs, we essentially used the planets' own gravity against each other. Precisely timing how they tug on their neighbors allowed us to calculate their masses, and sidestep the issues with this young star."

The results were remarkable. The planets, despite being 5 to 10 times the radius of Earth, were found to have masses of only 5 to 15 times that of our own world. This makes them incredibly low-density—more like planetary-sized cotton candy than rocky worlds.

“The unusually large radii of young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured," said Trevor David, a co-author from the Flatiron Institute who led the initial discovery of the system in 2019. "By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally 'puffy,' which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

This puffiness helps solve a long-standing puzzle in planet formation. A planet that simply forms and cools down over time would be much more compact. The team's analysis reveals that these planets must have undergone a dramatic transformation early in their lives, rapidly shedding much of their initial atmospheres and cooling dramatically when the gas-rich disk around their young star disappeared.

"These planets have already undergone a dramatic transformation, rapidly losing much of their original atmospheres and cooling faster than what we'd expect from standard models," explains James Owen, a co-author from Imperial College London who led the theoretical modeling. "But they're still evolving. Over the next few billion years, they will continue to lose their atmosphere and shrink significantly, transforming into the compact worlds we see throughout the galaxy."

“I’m reminded of the famous ‘Lucy’ fossil, one of our hominid ancestors that lived 3 million years ago and was one of the key ‘missing links’ between apes and humans,” added Petigura. “V1298Tau is a critical link between the star/planet forming nebulae we see all over the sky, and the mature planetary systems that we have now discovered by the thousands.”

The V1298 Tau system now serves as a crucial laboratory for understanding the origins of the most abundant planets in the Milky Way, giving scientists an unprecedented glimpse into the turbulent and transformative lives of young worlds. Understanding systems like V1298 Tau may also help explain why our own solar system lacks the super-Earths and sub-Neptunes that are so abundant elsewhere in the galaxy.

"This discovery fundamentally changes how we think about planetary systems," adds Livingston. "V1298 Tau shows us that today's super-Earths and sub-Neptunes start out as giant, puffy worlds that contract over time. We're essentially watching the universe's most successful planetary architecture in the making."

Journal

Nature

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

A young progenitor for the most common planetary systems in the Galaxy

Article Publication Date

7-Jan-2026

Scientists find evidence dark matter and neutrinos may interact, challenging standard model of the universe

Scientists are a step closer to solving one of the universe’s biggest mysteries as new research finds evidence that two of its least understood components may be interacting, offering a rare window into the darkest recesses of the cosmos.

The University of Sheffield findings relate to the relationship between dark matter, the mysterious, invisible substance that makes up around 85% of the matter in the universe, and neutrinos, one of the most fundamental and elusive subatomic particles. Scientists have overwhelming indirect evidence for the existence of dark matter, while neutrinos, though invisible and with an extremely small mass, have been observed using huge underground detectors.

The Standard Model of Cosmology (Lambda-CDM), with its origins in Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, posits that dark matter and neutrinos exist independently and do not interact with one another.

New University of Sheffield research published in the Nature Astronomy journal casts doubt on this theory, challenging the long-standing cosmological model. The research detects signs that these elusive cosmic components may interact, offering a rare glimpse into parts of the universe we can’t see or easily detect.

By combining data from different eras, scientists have found evidence of interactions between dark matter and neutrinos that could have affected the way cosmic structures, such as galaxies, formed over time.

The data spans the history of the universe:

Data regarding the early universe comes from two main sources: the highly sensitive ground-based Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT), and the Planck Telescope, a space observatory operated by the European Space Agency (ESA) from 2009 to 2013. Both instruments were specifically designed to study the faint afterglow of the Big Bang.

Late-universe data comes from a massive catalogue of astronomical observations taken by the Dark Energy Camera on the Victor M. Blanco Telescope in Chile, along with galaxy maps from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Co-author of the study Dr. Eleonora Di Valentino, a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sheffield, said: “The better we understand dark matter, the more insight we gain into how the Universe evolves and how its different components are connected.

“Our results address a long-standing puzzle in cosmology. Measurements of the early Universe predict that cosmic structures should have grown more strongly over time than what we observe today.

“However, observations of the modern Universe indicate that matter is slightly less clumped than expected, pointing to a mild mismatch between early- and late-time measurements.

“This tension does not mean the standard cosmological model is wrong, but it may suggest that it is incomplete.

“Our study shows that interactions between dark matter and neutrinos could help explain this difference, offering new insight into how structure formed in the Universe."

The findings set a clear path for further testing of the theory using more precise data from future telescopes, Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) experiments and weak lensing surveys, which use the subtle distortions of light from distant galaxies to map the distribution of mass throughout the universe.

Dr. William Giarè, co-author of the study and former Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Sheffield, now based at the University of Hawaiʻi, said: “If this interaction between dark matter and neutrinos is confirmed, it would be a fundamental breakthrough.

“It would not only shed new light on a persistent mismatch between different cosmological probes, but also provide particle physicists with a concrete direction, indicating which properties to look for in laboratory experiments to help finally unmask the true nature of dark matter.”

Journal

Nature Astronomy

Method of Research

Data/statistical analysis

Article Title

A solution to the S8 tension through neutrino–dark matter interactions

We finally know how the most common types of planets are created

Four baby planets show how super-Earths and sub-Neptunes form

University of California - Los Angeles

Four baby planets show how super-Earths and sub-Neptunes form

University of California - Los Angeles

Thanks to the discovery of thousands of exoplanets to date, we know that planets bigger than Earth but smaller than Neptune orbit most stars. Oddly, our sun lacks such a planet. That’s been a source of frustration for planetary scientists, who can’t study them in as much detail as they’d like, leaving one big question: How did these planets form?

Now we know the answer.

An international team of astrophysicists from UCLA and elsewhere has witnessed four baby planets in the V1298 Tau system in the process of becoming super-Earths and sub-Neptunes. The findings are published in the journal Nature.

“I’m reminded of the famous ‘Lucy’ fossil, one of our hominid ancestors that lived 3 million years ago and was one of the ‘missing links’ between apes and humans,” said UCLA professor of physics and astronomy and second author Erik Petigura. “V1298 Tau is a critical link between the star- and planet-forming nebulae we see all over the sky, and the mature planetary systems that we have now discovered by the thousands.”

How planets form

Planets form when a cloud of gas and dust, called a nebula, contracts under the force of gravity into a young star and a swirling disk of matter called a protoplanetary disk. Planets form from this disk of gas, but it’s a messy process. There are many ways a planet can grow or shrink in size during its infancy --- a period of a few hundred million years. This led to major questions about why so many mature planets were between the sizes of Earth and Neptune.

The star V1298 Tau is only about 20 million years old compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old sun. Expressed in human terms, it’s equivalent to a 5-month-old baby. Four giant, rapidly evolving planets between the sizes of Neptune and Jupiter orbit the star, but unlike growing babies, the new research shows that these planets are contracting in size and are steadily losing their atmospheres. Petigura and co-author Trevor David at the Flatiron Institute led the team that first discovered the planets in 2019.

“What’s so exciting is that we’re seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system,” said John Livingston, the study’s lead author from the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo, Japan. “The four planets we studied will likely contract into ‘super-Earths’ and ‘sub-Neptunes’—the most common types of planets in our galaxy, but we’ve never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.”

Observations, hunches and a stroke of good luck lead to a big discovery

The team made the discovery by observing the transits of the planets around their star from a network of ground-and space-based telescopes for nearly a decade. A transit is when a planet crosses in front of its star, dimming it slightly. By tracking the transit over time, scientists determine the trajectory and timing of the object’s orbit. By studying the details of the transits of all the planets in a system, scientists can learn a lot about what the planets are made of and how they interact with one another.

But the V1298 Tau system didn’t make this easy. In fact, the team wouldn’t have made their discovery at all if it weren’t for following hunches and a stroke of good luck.

“We had two transits for the outermost planet separated by several years, and we knew that we had missed many in between. There were hundreds of possibilities which we whittled down by running computer models and making educated guesses,” said Petigura.

The answer came as so much news does now. A Slack message from Livingston popped up on Petigura’s screen: “Hey, we got it from the ground!”

Livingston had recovered another transit of the elusive outermost planet using a ground-based telescope, pinning down its orbital period.

“I couldn’t believe it! The timing was so uncertain that I thought we would have to try half a dozen times at least. It was like getting a hole-in-one in golf,” said Petigura.

“The effort became more and more tantalizing as we went along,” said Livingston, who earned his undergraduate degree in astrophysics at UCLA. “We nearly had to resort to brute force to crack the mystery of the outer planet, only to get it right on our first try.”

How to weigh a baby planet

Once they sorted out the shapes and timing of the orbits of the four planets, the researchers could make sense of how the planets tugged on each other due to gravity, sometimes slowing down and sometimes speeding up, and leading to transits, sometimes occurring early and other times late. These transit and timing variations allowed the team to measure the masses of all four planets for the first time, which is akin to weighing them.

The shocking result? Despite being 5 to 10 times the radius of Earth, the planets had masses only 5 to 15 times larger than Earth. This means they are very low-density, comparable to Styrofoam, whereas the Earth has the density of rock.

“The unusually large radii of young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured,” said Trevor David, a co-author from the Flatiron Institute who led the initial discovery of the system in 2019. “By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally ‘puffy,’ which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

“Our measurements reveal they are incredibly lightweight — some of the least dense planets ever found. It’s a critical step that turns a long-standing theory about how planets mature into an observed reality,” said Livingston.

Measuring the masses and sizes of planets at a critical moment in their development helps astronomers understand how they evolve over time. The V1298 planets have already lost a significant amount of their upper gaseous layers and are destined to lose more.

“These planets have already undergone a dramatic transformation, rapidly losing much of their original atmospheres and cooled faster than what we’d expect from standard models,” said James Owen, a co-author from Imperial College London who led the theoretical modeling. “But they’re still evolving. Over the next few billion years, they will continue to lose their atmosphere and shrink significantly, transforming into the compact systems of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes we see throughout the galaxy.”

Journal

Nature

Nature

No comments:

Post a Comment