Normal life has ground to a halt in the region as businesses lay off workers, hospitals struggle to care for patients, and ordinary people despair.

Pranav Dixit BuzzFeed News Reporting From New Delhi February 26, 2020

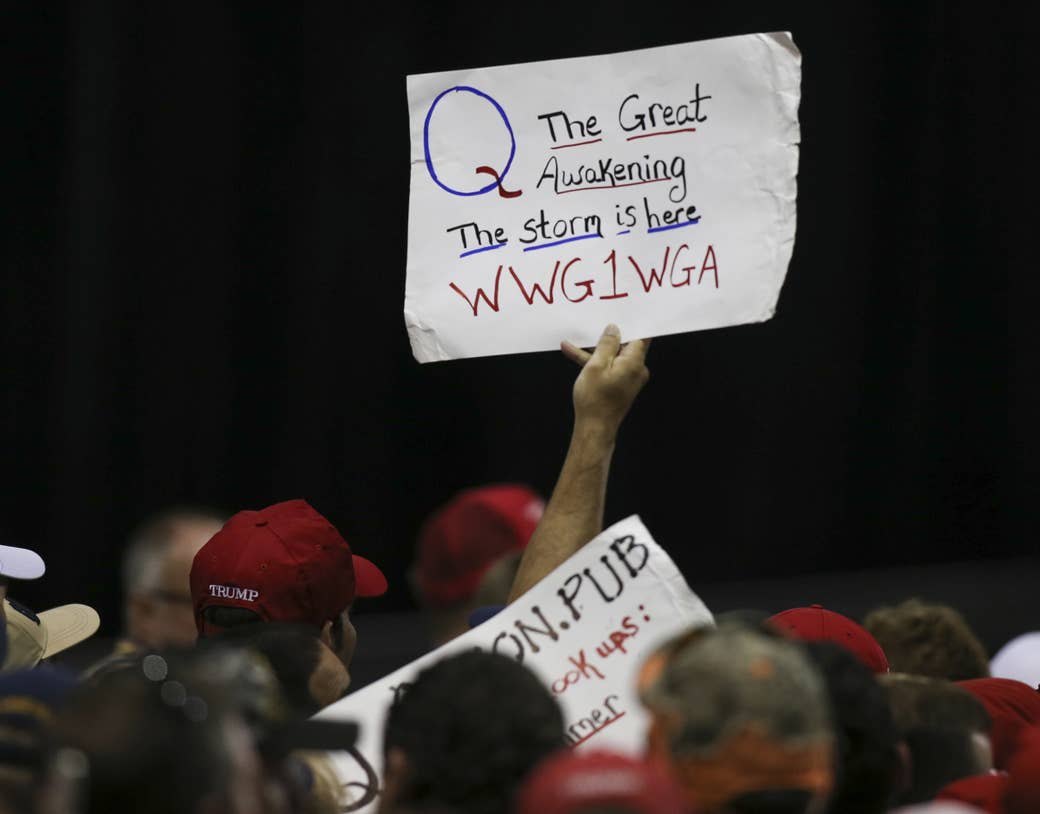

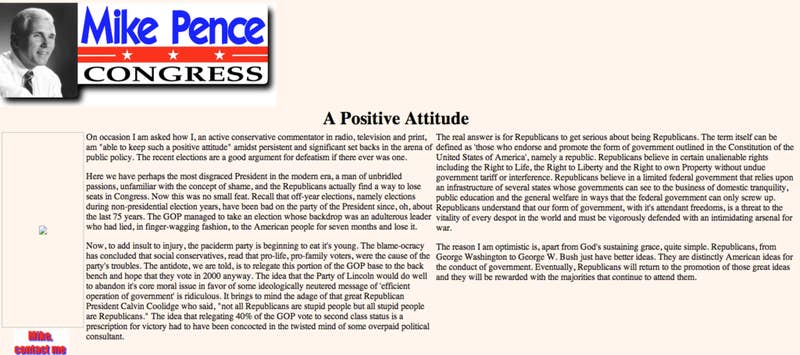

Sopa Images / Getty Images

A Kashmiri vendor walks past closed shops during the shutdown in Srinagar.

Like the snowcapped mountains and grassy meadows, men with guns are part of the landscape in Kashmir. Some are cops, some are from the Indian army, and some belong to a counterinsurgency force. Only locals, who have grown up with these men patrolling their streets for generations, can tell who is who.

On a cold winter morning in late January, a dozen of these armed men stood atop the roof of a one-story restaurant in Srinagar, Kashmir’s largest city and the region’s summer capital, and gazed down at the traffic below. I watched them watching my car, their bodies silhouetted against a steel sky. Blocks of snow lined the road, and as my car trundled into the heart of the city, my breath came out in misty puffs. When I instinctively pulled out my phone to check the weather, however, it was useless: Since August 5, Indian authorities have kept the people of Kashmir in a digital blackout, restricting most internet access. At 205 days and counting, it’s the longest-running internet shutdown in any democracy so far, seven months in March. That means no email. No WhatsApp. No maps. And no weather.

On August 5, India’s government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, revoked Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which granted the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir a measure of autonomy. The government split the state, a region disputed between India and Pakistan, into two territories. Supporters of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party hailed the move, while Kashmiris, many of whom want to see Kashmir join Pakistan or become independent, were angered. To prevent public opposition from turning into open rebellion, India’s government detained Kashmiri politicians, arrested thousands of activists and academics, and imposed a complete communications blackout. Overnight, mobile phones and landlines stopped working, broadband lines were frozen, and text messaging stopped.

Over the last six months, the government has relaxed some of these restrictions: Landline phones came back after five weeks, and in October, people who had postpaid mobile connections found they could make calls again. Last month, texting was allowed again, and eventually large swathes of Kashmir were able to access, at glacial speeds, a few hundred government-approved websites — which excluded social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, and messaging apps like WhatsApp. The lockdown continues despite India’s Supreme Court in January deeming “indefinite” suspension of internet services illegal.

“This internet shutdown is a human rights violation,” said Irfan Mehraj, a researcher at the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, a federation of human rights organizations in Kashmir that releases an annual report of Kashmir’s human rights situation each year. “It’s to break the will of the Kashmiri people.”

So, I went to see what the shutdown has done — the business people begging the police to restore access, the students clandestinely sharing videos, the doctors unable to do their jobs, and everywhere, the men with guns.

Almost every week since August, Isma Salaria has made the six-mile journey from her home in Srinagar to the Jammu and Kashmir police headquarters. The heavily guarded police department operates out of a sprawling, modern building fronted by panes of shiny blue glass and a sloping blue roof. During each visit, men frisk her half a dozen times.

She endures for a simple reason: Without internet access, her business, a center where students across the valley take online exams like the TOEFL, has nearly closed down. Unable to meet payroll, she’s had to lay off 20 of her 23 employees. One of the few women who owns a technology firm in the region, she’s grown desperate.

“I’ve pleaded so many times before [the authorities],” she says behind a wooden desk in a cramped room that has been her office for the last eight years. “I told them to give it to us on just one laptop. I told them, ‘Track the usage on that computer if you want.’ But no. They haven’t budged. This is the worst thing that could have happened to my business.”

“I was flying to New Delhi from Srinagar twice a week just to check my email.”

Internet access in Kashmir shows where you stand in the social hierarchy: If you’re powerful, you have it; if you’re not, you don’t. When I interviewed a senior police officer in Kupwara, he paused our conversation midway to talk to his dad in another part of the country on a WhatsApp video call — because law enforcement officials are among those at the top.

According to a Jammu and Kashmir government order, the government has 844 “e-terminals” and 69 special counters for tourists — relatively high in the pecking order — across the region to book train and flight tickets. But nobody seemed to know where to find one; when I finally do, it’s unstaffed and unusable.

Salaria's office is located in Rangreth, an area on the outskirts of Srinagar that locals refer to as Kashmir’s Silicon Valley. It’s a stretch of land a few miles long on a sloping hillside that is home to more than 30 software companies — everything from internet service providers to consulting firms that make bespoke software for international clients — which collectively employ around 1,200 people and bring in tens of millions of dollars yearly.

In December, a report released by the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry said that the lockdown had cost Kashmir’s economy more than $2.4 billion — and many of its leaders are frightened to speak out, facing economic losses, layoffs, and uncertainty.

“They have cut our throats,” says the CEO of a large Kashmiri IT company and internet service provider who declined to be identified because he was scared of police retaliation. “They’ve set us back 15 years.”

In August, immediately after the internet was shut down, Kashmiri law enforcement detained a senior official of his company for eight days in a cell 6 feet long and 6 feet wide for keeping communication lines open for an hour after an official shutdown was ordered. “I can’t tell you how worried his family was,” the CEO says.

Another CEO says his company received limited access after he petitioned the police more than 20 times to restore access. The agreement that he had to sign with the police before he got it states that his employees would not use social media or VPN software, send or receive encrypted files, and would use the internet strictly for business reasons.

“It was necessary,” he says. “I was flying to New Delhi from Srinagar twice a week just to check my email.”

But the company still lost millions of dollars in revenue from international clients and had to lay off nearly two-thirds of its 370 employees.

Dozens of IT companies in Srinagar have been signing these agreements with the police, but only a few of them have been allowed back online. Salaria is one of those who has yet to receive access, which has put her business on the brink of insolvency. In a November letter to the inspector general of the police in Kashmir, she pleaded with them to reactivate her connection. “We have suffered an unbearable loss,” she wrote.

When she spoke to me, she was a lot more blunt.

“Shutting down leased lines that are used by businesses is the stupidest thing you can do!” she says. “It’s a blot on democracy.”

Salaria has been to the police headquarters so often that officers there are now familiar with her. They scoff when they see her. “Oh look, these internet people are back,” she says. “They treat us like untouchables.”

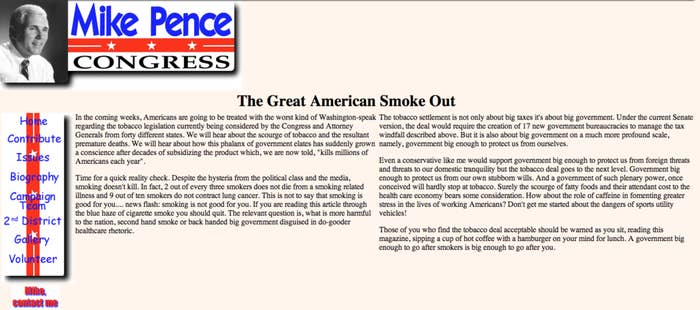

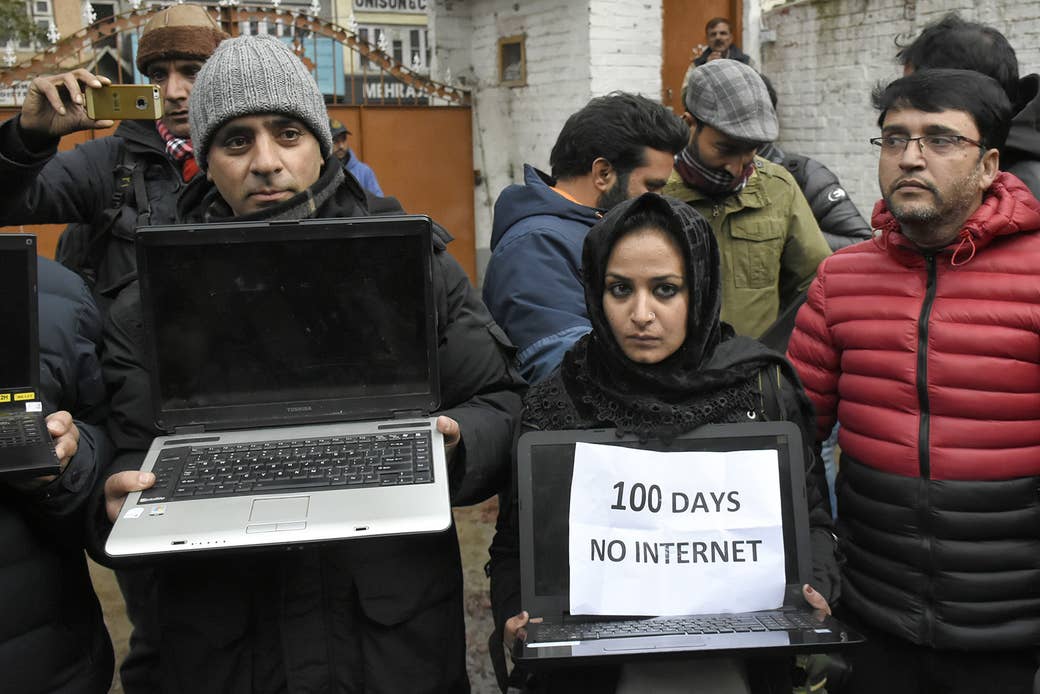

Nurphoto / Getty Images

Kashmiri journalists protest against the continuous internet blockade for the 100th day outside the Kashmir Press Club in Srinagar.

For hundreds of years, religion and politics have been intertwined in Kashmir.

In 1339, the first Muslim ruler conquered the region, beginning a period of Islamic rule that lasted for some five centuries. By the time the area came under British rule in 1846, the vast majority of the inhabitants practiced Islam — though not its titular Hindu rulers. At the time of partition in 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh dithered between joining Pakistan or India or remaining independent — until the issue was forced by an invasion by tribal forces from Pakistan. Singh appealed to India for troops, and the country agreed on the condition that he join his territories to theirs. He did, setting off the first Pakistan–India war, which lasted until the following year.

Although the United Nations called in for a plebiscite to determine which country Kashmir should join, no vote has ever taken place. Armed conflicts broke out again in 1965, 1971, and 1999.

In the ’90s, when the insurgency in Kashmir was at its peak, the Kupwara district, which lies on the border between the two countries, and which was one of the first two districts of Kashmir where access to government-approved websites over 2G speeds was approved in the middle of January, had some of the highest numbers of violent incidents in the region. Just over a hundred thousand people live in Kupwara. Most Indians wouldn't be able to find it on a map. The heavily militarized border between India and Pakistan known as the Line of Control, which US president Bill Clinton called "the most dangerous place in the world" lies on its west. Insurgency in Kupwara has calmed down in the last two decades, but as recently as 2018, Indian security forces killed 52 militants trying to infiltrate into Kupwara from across the border.

It’s here that Mir Hanan is waiting, desperate to speak. The 17-year-old Kashmiri medical student had been texting with me all day, but the inexpensive mobile plan that he used caps at 100 texts a day. “Can you call me?” he texts. “My SMS pack is almost exhausted.”

Hanan wasn’t yet born in the ’90s, but he’s grown up hearing stories of the insurgency. Right now, he’s worried about the future. “I don’t know what my future is,” he says.

When the current communications shutdown started in August, Hanan didn’t think much of it. Most Kashmiris, he says, are used to internet bans. “We are numbed to them,” he says. Young Kashmiris like Hanan grew up believing the internet would set them free. But unlike their peers around the world, regular shutdowns meant they learned to never take it for granted.

Since 2012, Indian authorities have shut down the internet in Kashmir 180 times, according to the Software Freedom Law Centre, a legal services organization in New Delhi that keeps a track of internet shutdowns. In 2017, for instance, the Kashmiri government abruptly blocked 22 social media platforms for a month to prevent them from “being misused by anti-national and anti-social elements.” At the time, Mohammed Faysal, founder of WithKashmir.org, a blogging platform for Kashmiris, told me how important social media was to Kashmiris. “Social media has allowed Kashmiris to humanize their struggles through photos and videos,” he said. “In a region torn by violence, platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter are 90% of our social lives. That’s what you’re taking away when you block them.”

The blackout has also spawned a medical emergency that could use the skills of someone like Hanan, as pharmacies run out of medicine and hospitals struggle to function. Last September, a month into the blackout, Javid Parsa, a restaurateur in New Delhi, told me about a bootleg network he had created to ship medicine into the region after communications were cut, using his popular Instagram page as a hub.

“Each day, I get three or four people traveling to Kashmir messaging me and offering to carry and deliver medicines and other essentials to people's families who are stuck there unable to ask anyone for help. Just yesterday, we found five patients in Southern Kashmir who urgently needed blood pressure medication,” he said in September.

People outside of Kashmir use his page as a place to organize shipments of medicine to family members in the region, creating a logistical network that spans some 550 kilometers by road.

“Thanks to my Instagram, we were able to find a guy driving there from Delhi who was able to carry the medicines and deliver them,” he said. “Unfortunately, thanks to the blackout, the people who do receive these medicines have no way of letting me know right now.”

In September, Al Jazeera reported from Srinagar on patients running out of money and doctors improvising surgeries. The following month, the New York Times reported that at least a dozen patients had died as a consequence. The British Medical Journal ran an editorial with the headline “Kashmir Communications Blackout Is Putting Patients at Risk, Doctors Warn.”

On a freezing Friday morning, I head to Kupwara to meet Hanan and his friends. Vast paddy fields smothered by snow and sprawling orchards dotted with trees, their branches bare and bony, flash by on either side of the winding road.

Halfway through the journey, outside the town of Sopore, two men in Indian Army fatigues and rifles slung across their chests flag us down and ask us to open our trunk. “They’re looking for guns,” says my traveling companion.

But it’s not just guns that the authorities are searching for. To enforce an internet blackout, the government has to ferret out all the ways people try to circumvent it, and stop them.

“When they question you in Kashmir, refusing is never an option.”

Last week, after a video went viral of an ailing, 90-year-old separatist leader named Syed Ali Geelani stating where he wished to be buried after his death, authorities filed complaints against people using VPN software to access social media under a law that lets the government imprison anyone it suspects belongs to “unlawful associations, terrorist gangs or terrorist organizations” for up to seven years.

A 32-year-old government contractor, who asked to remain anonymous to protect his safety, told me how members of the Indian Army stopped his car at a military checkpoint in Srinagar as he was driving home. “They made me get down from the car and unlock my phone,” he says. “Then they asked me if I had any VPN apps installed on my device.

“They stood there and watched over my shoulder to make sure I deleted those apps,” he says. “Refusing to show them your phone is never an option,” he added. “When they question you in Kashmir, refusing is never an option.”

Hanan and his friends meet us shortly before noon at Grand Resort, a small restaurant tucked away on a snow-covered lane in downtown Kupwara. We sit at a large table near a window at the back, trying to be inconspicuous, and order coffees and warm buttered toast, a popular snack in Kashmir. Nobody looks at their phones — there’s nothing to see on them.

The most obvious effects of the blackout are economic. Sofi Musaib, a high school senior who was preparing for the med school entrance exam when the shutdown began, says he’s decided to sit out a year because he’s simply not prepared. “Academic books and study material are expensive. But a mobile data plan is 149 rupees ($2) a month, so I used to rely on YouTube for watching lectures related to my course,” he says. “I don’t have Wi-Fi at home and I am not rich enough to move out of Kashmir to study somewhere else in the country.”

Zahid Ul-Aslam, a 17-year-old high school senior, calls the last six months a “black time.” Most of what we do on our phones is low stakes, and it’s no different for him. Ul-Aslam spent hours with friends, family, and college professors in a dozen WhatsApp groups, playing PUBG, an online multiplayer game, tracking cricket updates, catching up on news, and swiping through TikTok videos. “I don’t know what’s going on in the world anymore,” he says.

“I feel like there’s an iron curtain between the rest of the world and us,” says Khushgufter Afimed Shah-Pirzada, a 20-year-old linguistics undergrad. “We can move around, but we can’t see, feel, or breathe.”

“I thought it was bad enough when Burhan was martyred,” says Hanan, “but this is worse.”

In 2016, Indian security forces gunned down Burhan Wani, the leader of the Hizbul Mujahideen, Kashmir’s largest insurgent group, which wants the territory to become part of Pakistan. A handsome young man with a close-cropped beard, Wani differed from many militants because his claim to fame was social media.

Pictures and videos of Wani and his cohort wearing combat fatigues and cradling automatic weapons went viral on Facebook and WhatsApp across the valley. Wani not only threatened Indian security forces, but called upon young Kashmiris to revolt. To the Indians who killed him, Wani was a terrorist, but for the young Kashmiris sitting at the table with me, he was a symbol of resistance.

After Wani’s death, thousands of Kashmiris attended his funeral in the town of Tral, where he was born. One attendee called it a “carnival of martyrdom.” In the wake of violent protests following his death, in which more than 40 people died, authorities shut down the internet and mobile services for nearly six months.

Long before internet-enabled smartphones emerged as tools of dissent in India, and long before Wani, Kashmiris have used them to resist the Indian government. As a journalist based in Srinagar who didn’t want to be named for fear of retaliation said, “We had an Arab Spring in Kashmir long before the Arab Spring.”

Since Kashmir’s internet blackouts have made streaming services practically impossible to access, Kashmir has become a thriving black market for content. The current favorite is a Turkish historical epic called Resurrection: Ertugrul, which locals describe as a “Muslim Game of Thrones.” Kashmiris swap content over ShareIt, an app that zaps video and audio files, documents, and apps from phone to phone at high speeds without internet access, like AirDrop, but for Android. When Ul-Aslam opens the app, it shows that he has traded nearly a terabyte of content — as much as 15 full days of streaming Netflix would use — in the last six months.

His phone’s home screen is littered with VPN apps, which he’s gotten through ShareIt after the 2G network was restored in Kupwara. VPN software typically hides a user’s real location and encrypts data, which means that someone based in Kashmir could use a VPN to make it seem like they were located somewhere else in the country, bypassing local restrictions. The government bans people from using VPN during the shutdown, but enforcement is spotty.

When 2G-speed services were restored to Kupwara, Ul-Aslam fired them up one by one to see if he could bypass the restrictions and access the full internet, but nothing worked. “Now I just keep them on my phone,” he says with a rueful smile, “for hope.”

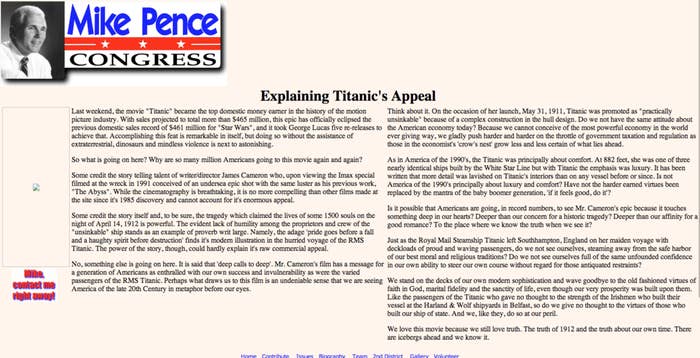

Hindustan Times / Getty Images

Journalists use internet facilities at the designated media center of the government's information department in Srinagar, Jan. 15.

The shutdown has also hampered the work of some members of Indian law enforcement.

At the end of January, Jammu and Kashmir police seized nearly $10 million in narcotics from two people in Kupwara. According to reports, the drugs were brought in through a network of smugglers from Pakistan-controlled Kashmir.

“The narco trade fuels a lot of the valley’s militancy because it brings in money,” a senior intelligence officer, who requested anonymity to speak freely, tells me at an Indian army camp near Kupwara. “Once the channel to bring in the drugs is set, they switch to bringing in weapons and, eventually, militants from across the border.”

To bust these operations, intelligence officials rely on tracking the cellphones of the people involved in them and intercepting calls and messages. But the shutdown put an end to that.

“The quality of intelligence has gone down drastically since the shutdown started,” the officer says. “Sure, it’s impacted militant networks too, but they don’t just rely on phones. Their physical networks and infrastructure are well established as well.”

The lack of mobile internet, especially, has made it harder for informants to reach out to Indian intelligence officials, he says.

“Whistleblowers would rarely call or text us,” he says, “because those things aren’t encrypted. They would either message or call over an encrypted app like WhatsApp or come and meet us in person.”

Since August, this officer says, he’s been unable to connect with any of his sources over WhatsApp. He now meets them only in person and has had to reestablish most of his network.

“The official reasons for shutting down the internet such as to prevent anti-national activities are true,” he says. “But shutting down the internet also impacts your ability to track the bad guys.”

Just off Residency Road, a wide, sycamore-lined street in the heart of Srinagar, sits a series of low-slung buildings with sloping green tin roofs inside a barbed wire fence.

Inside, two bored-looking security guards wave me through a metal detector. One of them has an automatic rifle casually slung across his chest. Directly across me is a thick, black curtain, which I brush aside to enter a space about the size of a small hotel room.

The air is stuffy, and it’s tough to move around without bumping into someone. Against a wall is a row of cubicles where groups of hassled men stare into flatscreen monitors. Some people sit on wooden chairs and tap on laptops connected to snaking ethernet cables. Someone trips across one, grabs my shoulder to steady themselves, and mutters an apology.

This is Kashmir’s Media Facilitation Center, a makeshift facility set up by the government for journalists, and one of the few places in Kashmir with unrestricted internet access. The center is segregated by gender — the space for women journalists is down a long corridor that leads to filthy restrooms — and has become the nerve center for local, national, and international media. There are nine desktop computers and a handful of ethernet cables to serve the approximately 300 journalists who work in Srinagar — though I doubt they could all fit in here at once. There’s no Wi-Fi, but Connectify, a crafty piece of software that lets you turn a laptop attached to an ethernet cable into a Wi-Fi hotspot that other devices around it can connect to, is all the rage.

“It’s not allowed, it’s restricted by the government,” a reporter tells me with a wink as he punches in the password. “But we do it anyway.”

When I check the laptop I’m mooching off, I discover there are 26 other people connected. “It can’t handle so many people using it at once” laughs the owner. In the corner, someone is downloading nursery rhymes from ChuChu TV, India’s largest YouTube channel for kids, on an iPad.

Few professions in Kashmir have been hit as badly by the internet shutdown as the region’s press. Newspapers and websites, unable to get in touch with their reporters, stopped publishing for weeks. Since August 5, the day the blackout was imposed, the government has detained dozens, withdrawn all-important government advertising from local newspapers, and stopped journalists at military checkpoints as they moved around the region. Official information comes in a trickle via anodyne press briefings.

“We’re not doing journalism anymore,” says Sajjad Haider, editor-in-chief of the Kashmir Observer, one of the region’s largest publications and the first to launch an online edition in 1997. “We’re putting out trash. We’re afraid of our readers. If they had a choice, they would stop reading Kashmiri newspapers.”

“We’re not doing journalism anymore. We’re putting out trash.”

Like most other publications in the region, a major source of Haider’s revenue source was ads in his newspaper taken out by the government. But since the shutdown, government advertising has dropped by half, he says. Private advertising from local businesses such as handicrafts and tourism, which have already been hit due to the shutdown, has disappeared almost completely. Nearly a dozen Kashmir Observer staffers lost their jobs because the paper couldn’t afford their salaries.

Haider has approached authorities multiple times since the shutdown but says that they have “absolutely not” been responsive to his pleas to restore access. “Every time, they just feign ignorance. You have to go higher and higher, and ultimately, we are told that the buck stops at New Delhi.”

Greater Kashmir, the region’s oldest and the largest newspaper, put more than half its newsroom on “standby” — leave without pay — according to executive editor Arif Wani. It last updated its website in December, for which a staff member had to travel outside the region to upload stories. That proved to be too expensive and unfeasible, and so it now sits frozen.

When I ask Haider, a grizzled news veteran, how he manages to keep up with the news, his eyes bulge and his hands fly up into the air. “I don’t!” he shouts. “I read old books! Old books on my bookshelves!”

Later that evening, I catch an auto rickshaw from Haider’s office to the center of the city, to attend a press conference by Ravi Shankar Prasad, India’s Information and Technology and Communications minister, who is in town to inaugurate a post office staffed exclusively by women. A throng of journalists waits for nearly 45 minutes watching dozens of heavily armed Indian Army personnel standing outside the gates.

Finally, Prasad draws up in an enormous black car, bulletproof windows shielded with dark film, followed by a convoy. We try to follow him, but the way is blocked: Only a few media outlets have been handpicked to attend the press conference. The rest of us trudge home.

A day later, India’s largest news agency publishes two paragraphs about Shankar’s visit to Srinagar. “Ravi Shankar Prasad interacts with locals,” reads the headline. It doesn’t mention the shutdown.

“You have to understand that the internet here is not just a utility,” a journalist who works for a national news website and who wished to remain unnamed tells me. “It’s now a tool for a new social hierarchy. At the top is the ruling class, the politicians. At the bottom — below the rest of the people, below the boat owners, below the auto rickshaw drivers — are the journalists. We are at the bottom, the wretched of the earth.”

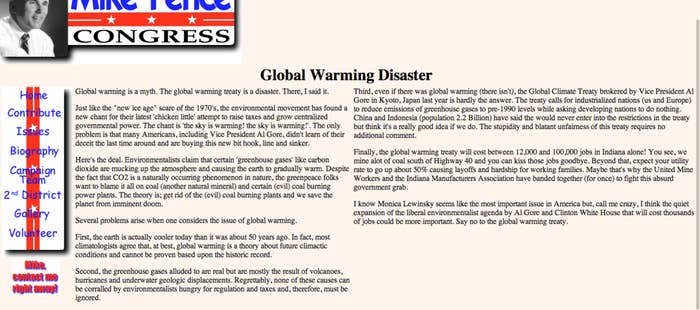

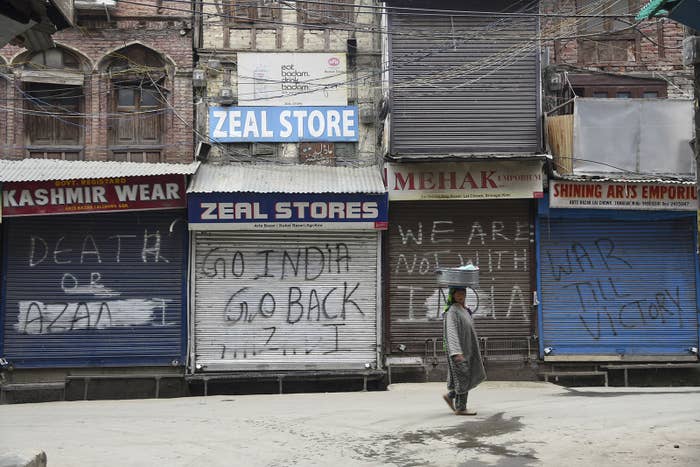

Sopa Images / Getty Images

A Kashmiri man installs a VPN application on his mobile phone in Srinagar.

On Republic Day, India marks the adoption of its constitution, which states that the country is a “sovereign socialist secular democratic republic”. Across the nation, people hoist the tricolor in public places. Patriotic songs blare from speakers, and members of the Indian Armed Forces showcase their might while marching down Rajpath, a ceremonial boulevard in New Delhi that leads to the official residence of the Indian president.

In Kashmir — which the constitution had, up until August, granted a degree of autonomy — Republic Day means lockdown. Mobile phones are shut off entirely. Roads are barricaded and concertina wire strung everywhere. Men clasping automatic rifles and bulletproof vests patrol every few feet. Stores and businesses close down, and most people stay indoors.

On my last day in Kashmir, hours before boarding my flight back to Delhi, I am finally plunged into the total communications blackout that Kashmiris lived through for weeks in August.

On the TV, every news channel is tuned in live to the Republic Day parade in New Delhi. On the screen, Prime Minister Narendra Modi wears a bright saffron turban and gives a firm handshake to India’s official Republic Day guest, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.

I crack my window open and gaze down at the empty street below. Nothing moves. Five minutes later, a dozen army men wearing metal helmets and carrying ballistic shields walk past. One of them detaches himself from the group and positions himself directly across the street. Once in a while, he looks up and stares at me staring down at him and our eyes meet in an unblinking gaze that he doesn’t break for a long time. I shut the window and draw the curtain.

Shortly after 10 a.m., I step out of the front door of the hotel and walk out into the empty streets of Srinagar. “Don’t go out if you don’t have to,” warns the man at the front desk, noting that I might be stopped and frisked and asked for ID.

Lal Chowk, Srinagar’s main city square, is a site of historical significance. In 1948, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, unfurled the Indian flag and promised Kashmiris a referendum to choose their political future. Four decades later, members of the Hindu nationalist BJP hoisted the tricolor a short distance away.

On this Republic Day, dozens of gun-toting men in army uniforms surround the tower. A small 5-year-old girl wearing pink, rabbit-shaped ear muffs holds her mother's hand and skips past the men. When I pass them again, I see a lanky young man with a camera clicking freely. He says he’s a photographer with an international wire service. “Don’t they get bothered when you do that?” I ask. “They do,” he shrugs. “Sometimes, they trash you.”

Shortly after lunchtime, I set off for the airport. My flight back home isn’t scheduled to take off before evening, but security is tight around the city on Republic Day and I don’t want to take any chances. In the eight-mile drive to the airport, army personnel stop my car twice, make me and the driver get off, and demand ID. When I tell them I have a flight to catch, they ask me to show my ticket. Half a mile before we reach the airport, I am stopped again, and this time, one of the men with guns pats me down and runs a wand over my bag.

As the cab pulls into the airport, a huge billboard with Modi’s face on it looms large beneath half a dozen tall sycamores. “Digital India, Developed India,” it says, name-checking one of the prime minister's flagship campaigns.

Moments before I board the flight, the Republic Day mobile ban is lifted, and backed up text messages start streaming in. It reminds of something Hanan told me in Kupwara. “They’ve made their point,” he had said. “Even if they give us the internet back, they can take it away any time again whenever they want, and as long as they want.” ●

Smartphones Transformed India. Now Indians Are Turning Them Against The Modi Government. Pranav Dixit · Dec. 26, 2019

Scaachi Koul · Dec. 18, 2019

Kashmiris Are Disappearing From WhatsApp Pranav Dixit · Dec. 4, 2019

This Is What It’s Like Living Through Kashmir’s Communications Blackout Pranav Dixit · Sept. 2, 2019

Pranav Dixit is a tech reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in Delhi.