A Failure of Intelligence: Part I

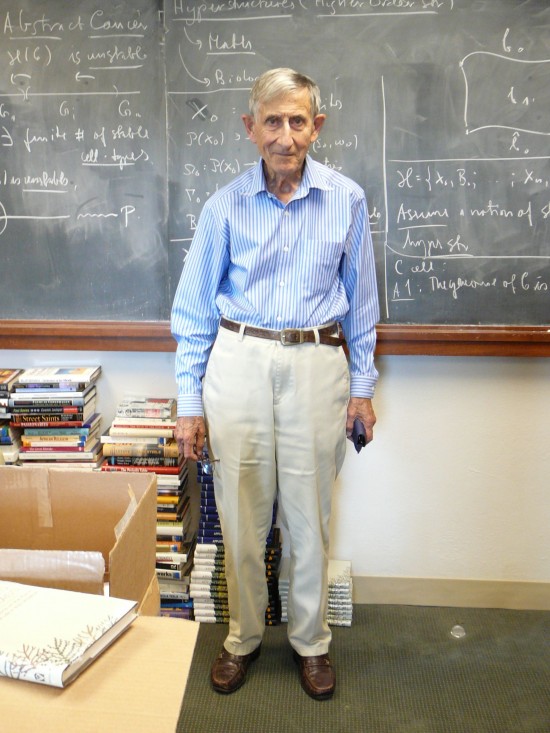

Prominent physicist Freeman Dyson recalls the time he spent developing analytical methods to help the British Royal Air Force bomb German targets during World War II.

by Freeman Dyson

Nov 1, 2006

Editor's note: Freeman Dyson, who died on February 28, 2020, wrote this essay in two parts for MIT Technology Review in 2006.

I began work in the Operational Research Section (ORS) of the British Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command on July 25, 1943. I was 19 years old, fresh from an abbreviated two years as a student at the University of Cambridge. The headquarters of Bomber Command was a substantial set of red brick buildings, hidden in the middle of a forest on top of a hill in the English county of Buckinghamshire. The main buildings had been built before the War. The ORS was added in 1941 and was housed in a collection of trailers at the back. Trees were growing right up to our windows, so we had little daylight even in summer. The Germans must have known where we were, but their planes never came to disturb us.

Air War: A British Lancaster bomber is silhouetted against flares and explosions during the attack on Hamburg, Germany, on the night of January 30, 1943. (Credit: Imperial War Museum)

This story is part of our November/December 2006

I was billeted in the home of the Parsons family in the village of Hughenden. Mrs. Parsons was a motherly soul and took good care of me. Once a week, she put her round tin bathtub out on her kitchen floor and filled it with hot water for my weekly splash. Each morning I bicycled the five miles up the hill to Bomber Command, and each evening I came coasting down. Sometimes, as I was struggling up the hill, an air force limousine would zoom by, and I would have a quick glimpse of our commander in chief, Sir Arthur Harris, sitting in the back, on his way to give the orders that sent thousands of boys my age to their deaths. Every day, depending on the weather and the readiness of the bombers, he would decide whether to send their crews out that night or let them rest. Every day, he chose the targets for the night.

“Bomber” Harris’s entire career had been devoted to the proposition that strategic bombing could defeat Germany without the use of land armies. The mammoth force of heavy bombers that he commanded had been planned by the British government in 1936 as our primary instrument for defeating Hitler without repeating the horrors of the trench warfare of World War I. Bomber Command, by itself, was absorbing about one-quarter of the entire British war effort.

The members of Bomber Command’s ORS were civilians, employed by the Ministry of Aircraft Production and not by the air force. The idea was that we would provide senior officers with independent scientific and technical advice. The experimental physicist Patrick Blackett had invented the ORS system in order to give advice to the navy. One of the crucial problems for the navy was to verify scientifically the destruction of U-boats. Every ship or airplane that dropped a depth charge somewhere near a U-boat was apt to claim a kill. An independent group of scientists was needed to evaluate the evidence impartially and find out which tactics were effective.

Bomber Command had a similar problem in evaluating the effectiveness of bombing. Aircrew frequently reported the destruction of targets when photographs showed they had missed by several miles. The navy ORS was extremely effective and made great contributions to winning the war against the U-boats in the Atlantic. But Blackett had two enormous advantages. First, he was a world-renowned scientist (who would later win a Nobel Prize), with a safe job in the academic world, so he could threaten to resign if his advice was not followed. Second, he had been a navy officer in World War I and was respected by the admirals he advised. Basil Dickins, the chief of our ORS at Bomber Command, had neither of these advantages. He was a civil servant with no independent standing. He could not threaten to resign, and Sir Arthur Harris had no respect for him. His career depended on telling Sir Arthur things that Sir Arthur wanted to hear. So that is what he did. He gave Sir Arthur information rather than advice. He never raised serious questions about Sir Arthur’s tactics and strategy.

Our ORS was divided into sections and subsections. The sections were ORS1, concerned with bombing effectiveness; ORS2, concerned with bomber losses; ORS3, concerned with history. My boss, Reuben Smeed, was chief of ORS2. The subsections of ORS2 were ORS2a, collecting crew reports and investigating causes of losses; ORS2b, studying the effectiveness of electronic countermeasures; ORS2c, studying damage to returning bombers; ORS2d, doing statistical analysis and other jobs requiring some mathematical skill. I was put into ORS2d.

Two other new boys arrived at the same time I did. One was John Carthy, who was in ORS1; the other was Mike O’Loughlin, who shared an office with me in ORS2d. John had been a leading actor in the Cambridge University student theater. Mike had been briefly in the army but was discharged when he was found to be epileptic. John and Mike and I became lifelong friends. John was cheerful, Mike was bitter, and I was somewhere in between. In later life, John was a biologist at the University of London, and Mike taught engineering at the Cambridge Polytechnic. After retiring from the Polytechnic, Mike became an Anglican minister in the parish of Linton, near Cambridge.

The ORS consisted of about 30 people, a mixed bunch of civil servants, academic experts, and students. Working with us were an equal number of WAAFs, girls of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, who wore blue uniforms and were subject to military discipline. The WAAFs were photographic interpreters, calculators, technicians, drivers, and secretaries. They did most of the real work of the ORS. They also supplied us with tea and sympathy. They made a depressing situation bearable. Their leader was Sergeant Asplen, a tall and strikingly beautiful girl whose authority was never questioned. The sergeant kept herself free of romantic entanglements. But two of her charges, a vivacious redhead named Dorothy and a more thoughtful brunette called Betty, became attached to my friends John and Mike. Love affairs were not officially discouraged. We celebrated two weddings before the War was over, with Dorothy and Betty discarding their dumpy blue uniforms for an afternoon and appearing resplendent in white silk. The marriages endured, and each afterwards produced four children.

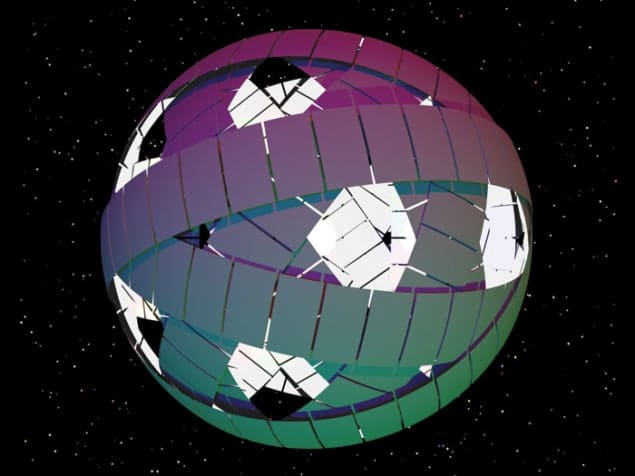

My first day of work was the day after one of our most successful operations, a full-force night attack on Hamburg. For the first time, the bombers had used the decoy system, which we called WINDOW and the Americans called CHAFF. WINDOW consisted of packets of paper strips coated with aluminum paint. One crew member in each bomber was responsible for throwing packets of WINDOW down a chute, at a rate of one packet per minute, while flying over Germany. The paper strips floated slowly down through the stream of bombers, each strip a resonant antenna tuned to the frequency of the German radars. The purpose was to confuse the radars so that they could not track individual bombers in the clutter of echoes from the WINDOW.

That day, the people at the ORS were joyful. I never saw them as joyful again until the day that the war in Europe ended. WINDOW had worked. The bomber losses the night before were only 12 out of 791, or 1.5 percent, far fewer than would have been expected for a major operation in July, when the skies in northern Europe are never really dark. Losses were usually about 5 percent and were mostly due to German night fighters, guided to the bombers by radars on the ground. WINDOW had cut the expected losses by two-thirds. Each bomber carried a crew of seven, so WINDOW that night had saved the lives of about 180 of our boys.

The first job that Reuben Smeed gave me to do when I arrived was to draw pictures of the cloud of WINDOW trailing through the stream of bombers as the night progressed, taking into account the local winds at various altitudes as measured and reported by the bombers. My pictures would be shown to the aircrew to impress on them how important it was for them to stay within the stream after bombing the target, rather than flying home independently.

Smeed explained to me that the same principles applied to bombers flying at night over Germany and to ships crossing the Atlantic. Ships had to travel in convoys, because the risk of being torpedoed by a U-boat was much greater for a ship traveling alone. For the same reason, bombers had to travel in streams: the risk of being tracked by radar and shot down by an enemy fighter was much greater for a bomber flying alone. But the crews tried to keep out of the bomber stream, because they were more afraid of collisions than of fighters. Every time they flew in the stream, they would see bombers coming close and almost colliding with them, but they almost never saw fighters. The German night fighter force was tiny compared with Bomber Command. But the German pilots were highly skilled, and they hardly ever got shot down. They carried a firing system called Schräge Musik, or “crooked music,” which allowed them to fly underneath a bomber and fire guns upward at a 60-degree angle. The fighter could see the bomber clearly silhouetted against the night sky, while the bomber could not see the fighter. This system efficiently destroyed thousands of bombers, and we did not even know that it existed. This was the greatest failure of the ORS. We learned about Schräge Musik too late to do anything to counter it.

Smeed believed the crew’s judgement was wrong. He thought a bomber’s chance of being shot down by a fighter was far greater than its chance of colliding with another bomber, even in the densest part of the bomber stream. But he had no evidence: he had been too busy with other urgent problems to collect any. He told me that the most useful thing I could do was to become Bomber Command’s expert on collisions. When not otherwise employed, I should collect all the scraps of evidence I could find about fatal and nonfatal collisions and put them all together. Then perhaps we could convince the aircrew that they were really safer staying in the stream.

There were two possible ways to study collisions, using theory or using observations. I tried both. The theoretical way was to use a formula: collision rate for a bomber flying in the stream equals density of bombers multiplied by average relative velocity of two bombers multiplied by mutual presentation area (MPA). The MPA was the area in a geometric plane perpendicular to the relative velocity within which a collision could occur. It was the same thing that atomic and particle physicists call a collision cross section. For vertical collisions, it was roughly four times the area of a bomber as seen from above. The formula assumes that two bombers on a collision course do not see each other in time to break off. For bombers flying at night over Germany, that assumption was probably true.

All three factors in the collision formula were uncertain. The MPA would be smaller for a sideways collision than for an up-and-down collision, but I assumed that most of the collisions would be up-and-down, with the relative velocity vertical. The relative velocity would depend on how vigorously the bombers were corkscrewing as they flew. Except during bombing runs over a target, they never flew straight and level; that would have left them sitting ducks for antiaircraft guns. The standard maneuver for avoiding antiaircraft fire was the corkscrew, combining side-to-side with up-and-down weaving. For predicting collisions, it was the up-and-down motion that was most important. From crew reports I estimated up-and-down motions averaging 40 miles an hour, uncertain by a factor of two. But the dominant uncertainty in the collision formula was the density of bombers in the stream.

I studied the crew reports, which sometimes described large deviations from the tracks that the bombers were supposed to fly. For the majority of crews, who reported no large deviations, there was no way to tell how close to their assigned tracks they actually flew. My best estimate of the density of bombers was uncertain by a factor of 10. This made the collision formula practically worthless as a predictive tool. But it still had value as a way to set an upper bound on the collision rate. If I assumed maximum values for all three factors in the formula, it gave a loss rate due to collisions of 1 percent per operation. One percent was much too high to be acceptable, but still less than the overall loss rate of 5 percent. Even if we squeezed the bomber stream to the highest possible density, collisions would not be the main cause of losses.

How common, really, were collisions? Observational evidence of lethal crashes over Germany was plentiful but unreliable. The crews frequently reported seeing events that looked like collisions: first an explosion in the air, and then two flaming objects falling to the ground. These events were visible from great distances and were often multiply reported. The crews tended to believe that they were seeing collisions, but there was no way to be sure. Most of the events probably involved single bombers, hit by antiaircraft shells or by fighter cannon fire, that broke in half as they disintegrated.

In the end I found only two sources of evidence that I could trust: bombers that collided over England and bombers that returned damaged by nonlethal collisions over Germany. The numbers of incidents of both kinds were reliable, and small enough that I could investigate each case individually. The case that I remember best was a collision between two Mosquito bombers over Munich. The Mosquito was a light, two-seat bomber that Bomber Command used extensively for small-scale attacks, to confuse the German defenses and distract attention from the heavy attacks. Two Mosquitoes flew alone from England to Munich and then collided over the target, with only minor damage. It was obvious that the collision could not have been the result of normal operations. The two pilots must have seen each other when they got to Munich and started playing games. The Mosquito was fast and maneuverable and hardly ever got shot down, so the pilots felt themselves to be invulnerable. I interviewed Pilot-Officer Izatt, who was one of the two pilots. When I gently questioned him about the Munich operation, he confessed that he and his friend had been enjoying a dogfight over the target when they bumped into each other. So I crossed the Munich collision off my list. It was not relevant to the statistics on collisions between heavy bombers in the bomber stream. There remained seven authentic nonlethal collisions between heavy bombers over Germany.

For bombers flying at night over England in training exercises, I knew the numbers of lethal and nonlethal collisions. After more than 60 years, I can’t recall them precisely, but I remember that the ratio of lethal to nonlethal collisions was three to one. If I assumed that the chance of surviving a collision was the same over Germany as over England, then it was simple to calculate the number of lethal collisions over Germany. But there were two reasons that assumption might be false. On the one hand, a badly damaged aircraft over Germany might fail to get home, while an aircraft with the same damage over England could make a safe landing. On the other hand, the crew of a damaged aircraft over England might decide to bail out and let the plane crash, while the same crew over Germany would be strongly motivated to bring the plane home. There was no way to incorporate these distinctions into my calculations. But since they pulled in opposite directions, I decided to ignore them both. I estimated the number of lethal collisions over Germany in the time since the massive attacks began to be three times the number of nonlethal collisions, or 21. These numbers referred to major operations over Germany with high-density bomber streams, in which about 60,000 sorties had been flown at the time I did the calculation. So collisions destroyed 42 aircraft in 60,000 sorties, a loss rate of .07 percent. This was the best estimate I could make. I could not calculate any reliable limits of error, but I felt confident that the estimate was correct within a factor of two. It was consistent with the less accurate estimate obtained from the theoretical formula, and it strongly confirmed Smeed’s belief that collisions were a smaller risk than fighters.

For a week after I arrived at the ORS, the attacks on Hamburg continued. The second, on July 27, raised a firestorm that devastated the central part of the city and killed about 40,000 people. We succeeded in raising firestorms only twice, once in Hamburg and once more in Dresden in 1945, where between 25,000 and 60,000 people perished (the numbers are still debated). The Germans had good air raid shelters and warning systems and did what they were told. As a result, only a few thousand people were killed in a typical major attack. But when there was a firestorm, people were asphyxiated or roasted inside their shelters, and the number killed was more than 10 times greater. Every time Bomber Command attacked a city, we were trying to raise a firestorm, but we never learnt why we so seldom succeeded. Probably a firestorm could happen only when three things occurred together: first, a high concentration of old buildings at the target site; second, an attack with a high density of incendiary bombs in the target’s central area; and, third, an atmospheric instability. When the combination of these three things was just right, the flames and the winds produced a blazing hurricane. The same thing happened one night in Tokyo in March 1945 and once more at Hiroshima the following August. The Tokyo firestorm was the biggest, killing perhaps 100,000 people.

The third Hamburg raid was on the night of July 29, and the fourth on August 2. After the firestorm, the law of diminishing returns was operating. The fourth attack was a fiasco, with high and heavy clouds over the city and bombs scattered over the countryside. Our bomber losses were rising, close to 4 percent for the third attack and a little over 4 percent for the fourth. The Germans had learnt quickly how to deal with WINDOW. Since they could no longer track individual bombers with radar, they guided their fighters into the bomber stream and let them find their own targets. Within a month, loss rates were back at the 5 percent level, and WINDOW was no longer saving lives.

Another job that Smeed gave me was to invent ways to estimate the effectiveness of various countermeasures, using all the evidence from a heterogeneous collection of operations. The first countermeasure that I worked on was MONICA. MONICA was a tail-mounted warning radar that emitted a high-pitched squeal over the intercom when a bomber had another aircraft close behind it. The squeals came more rapidly as the distance measured by the radar became shorter. The crews disliked MONICA because it was too sensitive and raised many false alarms. They usually switched it off so that they could talk to each other without interruption. My job was to see from the results of many operations whether MONICA actually saved lives. I had to compare the loss rates of bombers with and without MONICA. This was difficult because MONICA was distributed unevenly among the squadrons. It was given preferentially to Halifaxes (one of the two main types of British heavy bomber), which usually had higher loss rates, and less often to Lancaster bombers, which usually had lower loss rates. In addition, Halifaxes were sent preferentially on less dangerous operations and Lancasters on more dangerous operations. To use all the evidence from Halifax and Lancaster losses on a variety of operations, I invented a method that was later reinvented by epidemiologists and given the name “meta-analysis.” Assembling the evidence from many operations to judge the effectiveness of MONICA was just like assembling the evidence from many clinical trials to judge the effectiveness of a drug.

My method of meta-analysis was the following: First, I subdivided the data by operation and by type of aircraft. For example, one subdivision would be Halifaxes on Bremen on March 5; another would be Lancasters on Berlin on December 2. In each subdivision I tabulated the number of aircraft with and without MONICA and the number lost with and without MONICA. I also tabulated the number of MONICA aircraft expected to be lost if the warning system had no effect, and the statistical variance of that number. So I had two quantities for each subdivision: observed-minus-expected losses of MONICA aircraft, and the variance of this difference. I assumed that the distributions of losses in the various subdivisions were uncorrelated. Thus, I could simply add up the two quantities, observed-minus-expected losses and variance, over all the subdivisions. The result was a total observed-minus-expected losses and variance for all the MONICA aircraft, unbiased by the different fractions of MONICA aircraft in the various subdivisions. This was a sensitive test of effectiveness, making use of all the available information. If the total of observed-minus-expected losses was significantly negative, it meant that MONICA was effective. But instead, the total was slightly positive and less than the square root of the total variance. MONICA was statistically worthless. The crews had been right when they decided to switch it off.

I later applied the same method of analysis to the question of whether experience helped crews to survive. Bomber Command told the crews that their chances of survival would increase with experience, and the crews believed it. They were told, After you have got through the first few operations, things will get better. This idea was important for morale at a time when the fraction of crews surviving to the end of a 30-operation tour was only about 25 percent. I subdivided the experienced and inexperienced crews on each operation and did the analysis, and again, the result was clear. Experience did not reduce loss rates. The cause of losses, whatever it was, killed novice and expert crews impartially. This result contradicted the official dogma, and the Command never accepted it. I blame the ORS, and I blame myself in particular, for not taking this result seriously enough. The evidence showed that the main cause of losses was an attack that gave experienced crews no chance either to escape or to defend themselves. If we had taken the evidence more seriously, we might have discovered Schräge Musik in time to respond with effective countermeasures.

Smeed and I agreed that Bomber Command could substantially reduce losses by ripping out two gun turrets, with all their associated hardware, from each bomber and reducing each crew from seven to five. The gun turrets were costly in aerodynamic drag as well as in weight. The turretless bombers would have flown 50 miles an hour faster and would have spent much less time over Germany. The evidence that experience did not reduce losses confirmed our opinion that the turrets were useless. The turrets did not save bombers, because the gunners rarely saw the fighters that killed them. But our proposal to rip out the turrets went against the official mythology of the gallant gunners defending their crewmates. Dickins never had the courage to push the issue seriously in his conversations with Harris. If he had, Harris might even have listened, and thousands of crewmen might have been saved.

The part of his job that Smeed enjoyed most was interviewing evaders. Evaders were crew members who had survived being shot down over German-occupied countries and made their way back to England. About 1 percent of all those shot down came back. Each week, Smeed would go to London and interview one or two of them. Sometimes he would take me along. We were not supposed to ask them questions about how they got back, but they would sometimes tell us amazing stories anyway. We were supposed to ask them questions about how they were shot down. But they had very little information to give us about that. Most of them said they never saw a fighter and had no warning of an attack. There was just a sudden burst of cannon fire, and the aircraft fell apart around them. Again, we missed an essential clue that might have led us to Schräge Musik.

On November 18, 1943, Sir Arthur Harris started the Battle of Berlin. This was his last chance to prove the proposition that strategic bombing could win wars. He announced that the Battle of Berlin would knock Germany out of the War. In November 1943, Harris’s bomber force was finally ready to do what it was designed to do: smash Hitler’s empire by demolishing Berlin. The Battle of Berlin started with a success, like the first attack on Hamburg on July 24. We attacked Berlin with 444 bombers, and only 9 were lost. Our losses were small, not because of WINDOW, but because of clever tactics. Two bomber forces were out that night, one going to Berlin and one to Mannheim. The German controllers were confused and sent most of the fighters to Mannheim.

After that first attempt on Berlin, Sir Arthur ordered 15 more heavy attacks, expecting to destroy that city as thoroughly as he had destroyed Hamburg. All through the winter of 1943 and ‘44, the bombers hammered away at Berlin. The weather that winter was worse than usual, covering the city with cloud for weeks on end. Our photoreconnaissance planes could bring back no pictures to show how poorly we were doing. As the attacks went on, the German defenses grew stronger, our losses heavier, and the “scatter” of the bombs worse. We never raised a firestorm in Berlin. On March 24, in the last of the 16 attacks, we lost 72 out of 791 bombers, a loss rate of 9 percent, and Sir Arthur admitted defeat. The battle cost us 492 bombers with more than 3,000 aircrew. For all that, industrial production in Berlin continued to increase, and the operations of government were never seriously disrupted.

There were two main reasons why Germany won the Battle of Berlin. First, the city is more modern and less dense than Hamburg, spread out over an area as large as London with only half of London’s population; so it did not burn well. Second, the repeated attacks along the same routes allowed the German fighters to find the bomber stream earlier and kill bombers more efficiently.

A week after the final attack on Berlin, we suffered an even more crushing defeat. We attacked Nuremberg with 795 bombers and lost 94, a loss rate of almost 12 percent. It was then clear to everybody that such losses were unsustainable. Sir Arthur reluctantly abandoned his dream of winning the War by himself. Bomber Command stopped flying so deep into Germany and spent the summer of 1944 giving tactical support to the Allied armies that were, by then, invading France.

The history of the 20th century has repeatedly shown that strategic bombing by itself does not win wars. If Britain had decided in 1936 to put its main effort into building ships instead of bombers, the invasion of France might have been possible in 1943 instead of 1944, and the war in Europe might have ended in 1944 instead of 1945. But in 1943, we had the bombers, and we did not have the ships, and the problem was to do the best we could with what we had.

One of our group of young students at the ORS was Sebastian Pease, known to his friends as Bas. He had joined the ORS only six months before I had, but by the time I got there, he already knew his way around and was at home in that alien world. He was the only one of us who was actually doing what we were all supposed to be doing: helping to win the War. The rest of us were sitting at Command Headquarters, depressed and miserable because our losses of aircraft and aircrew were tremendous and we were unable to do much to help. The Command did not like it when civilians wandered around operational squadrons collecting information, so we were mostly confined to our gloomy offices at the headquarters. But Bas succeeded in breaking out. He spent most of his time with the squadrons and came back to headquarters only occasionally. Fifty years later, when he was visiting Princeton (where I spent most of my life, working as a professor of physics), he told me what he had been doing.

Bas was able to escape from Command Headquarters because he was the expert in charge of a precise navigation system called G-H. Only a small number of bombers were fitted with G-H, because it required two-way communication with ground stations. These bombers belonged to two special squadrons, 218 Squadron being one of them. The G-H bombers were Stirlings, slow and ponderous machines that were due to be replaced by the smaller and more agile Lancasters. They did not take part in mass-bombing operations with the rest of the Command but did small, precise operations on their own with very low losses. Bas spent a lot of time at 218 Squadron and made sure that the G-H crews knew how to use their equipment to bomb accurately. He had “a good war,” as we used to say in those days. The rest of us were having a bad war.

Sometime early in 1944, 218 Squadron stopped bombing and started training for a highly secret operation called GLIMMER, which Bas helped to plan, and whose purpose was to divert German attention from the invasion fleet that was to invade France in June. The operation was carried out on the night of June 5-6. The G-H bombers flew low, in tight circles, dropping WINDOW as they moved slowly out over the English Channel. In conjunction with boats below them that carried specially designed radar transponders, they appeared to the German radars to be a fleet of ships. While the real invasion fleet was moving out toward Normandy, the fake invasion fleet of G-H bombers was moving out toward the Pas de Calais, 200 miles to the east. The ruse was successful, and the strong German forces in the Pas de Calais did not move to Normandy in time to stop the invasion. While Bas was training the crews, he said nothing about it to his friends at the ORS. We knew only that he was out at the squadrons doing something useful. Even when GLIMMER was over and the invasion had succeeded, Bas never spoke about it. My boss, Reuben Smeed, was a man of considerable wisdom. One day at Bomber Command, he said, “In this business, you have a choice. Either you get something done or you get the credit for it, but not both.” Bas’s work was a fine example of Smeed’s dictum. He made his choice, and he got something done. In later life he became a famous plasma physicist and ran the Joint European Torus, the main fusion program of the European Union.

The one time that I did something practically useful for Bomber Command was in spring 1944, when Smeed sent me to make accurate measurements of the brightness of the night sky as a function of time, angle, and altitude. The measurements would be used by our route planners to minimize the exposure of bombers to the long summer twilight over Germany. I went to an airfield at the village of Shawbury in Shropshire and flew for several nights in an old Hudson aircraft, unheated and unpressurized. The pilot flew back and forth on a prescribed course at various altitudes, while I took readings of sky brightness through an open window with an antiquated photometer, starting soon after sunset and ending when the sun was 18 degrees below the horizon. I was surprised to find that I could function quite well without oxygen at 20,000 feet. I shared this job with J. F. Cox, a Belgian professor who was caught in England when Hitler overran Belgium in 1940. Cox and I took turns doing the measurements. My flights were uneventful, but on the last of Cox’s flights, both of the Hudson’s engines failed, and the pilot decided to bail out. Cox also bailed out and came to earth still carrying the photometer. He broke an ankle but saved the device. In later years, he became rector of the Free University in Brussels.

After the War, Smeed worked for the British government on road traffic problems and then taught at University College London, where he was the first professor of traffic studies. He applied the methods of operational research to traffic problems all over the world and designed intelligent traffic-light control systems to optimize the flow of traffic through cities. Smeed had a fatalistic view of traffic flow. He said that the average speed of traffic in central London would always be nine miles per hour, because that is the minimum speed that people will tolerate. Intelligent use of traffic lights might increase the number of cars on the roads but would not increase their speed. As soon as the traffic flowed faster, more drivers would come to slow it down.

Smeed also had a fatalistic view of traffic accidents. He collected statistics on traffic deaths from many countries, all the way back to the invention of the automobile. He found that under an enormous range of conditions, the number of deaths in a country per year is given by a simple formula: number of deaths equals .0003 times the two-thirds power of the number of people times the one-third power of the number of cars. This formula is known as Smeed’s Law. He published it in 1949, and it is still valid 57 years later. It is, of course, not exact, but it holds within a factor of two for almost all countries at almost all times. It is remarkable that the number of deaths does not depend strongly on the size of the country, the quality of the roads, the rules and regulations governing traffic, or the safety equipment installed in cars. Smeed interpreted his law as a law of human nature. The number of deaths is determined mainly by psychological factors that are independent of material circumstances. People will drive recklessly until the number of deaths reaches the maximum they can tolerate. When the number exceeds that limit, they drive more carefully. Smeed’s Law merely defines the number of deaths that we find psychologically tolerable.

The last year of the War was quiet at ORS Bomber Command. We knew that the War was coming to an end and that nothing we could do would make much difference. With or without our help, Bomber Command was doing better. In the fall of 1944, when the Germans were driven out of France, it finally became possible for our bombers to make accurate and devastating night attacks on German oil refineries and synthetic-oil-production plants. We had long known these targets to be crucial to Germany’s war economy, but we had never been able to attack them effectively. That changed for two reasons. First, the loss of France made the German fighter defenses much less effective. Second, a new method of organizing attacks was invented by 5 Group, the most independent of the Bomber Command groups. The method originated with 617 Squadron, one of the 5 Group squadrons, which carried out the famous attack on the Ruhr dams in March 1943. The good idea, as usually happens in large organizations, percolated up from the bottom rather than trickling down from the top. The approach called for a “master bomber” who would fly a Mosquito at low altitude over a target, directing the attack by radio in plain language. The master bomber would first mark the target accurately with target indicator flares and then tell the heavy bombers overhead precisely where to aim. A deputy master bomber in another Mosquito was ready to take over in case the first one was shot down. Five Group carried out many such precision attacks with great success and low losses, while the other groups flew to other places and distracted the fighter defenses. In the last winter of the War, the German army and air force finally began to run out of oil. Bomber Command could justly claim to have helped the Allied armies who were fighting their way into Germany from east and west.

While the attacks on oil plants were helping to win the War, Sir Arthur continued to order major attacks on cities, including the attack on Dresden on the night of February 13, 1945. The Dresden attack became famous because it caused a firestorm and killed a large number of civilians, many of them refugees fleeing from the Russian armies that were overrunning Pomerania and Silesia. It caused some people in Britain to question the morality of continuing the wholesale slaughter of civilian populations when the War was almost over. Some of us were sickened by Sir Arthur’s unrelenting ferocity. But our feelings of revulsion after the Dresden attack were not widely shared. The British public at that time still had bitter memories of World War I, when German armies brought untold misery and destruction to other people’s countries, but German civilians never suffered the horrors of war in their own homes. The British mostly supported Sir Arthur’s ruthless bombing of cities, not because they believed that it was militarily necessary, but because they felt it was teaching German civilians a good lesson. This time, the German civilians were finally feeling the pain of war on their own skins.

I remember arguing about the morality of city bombing with the wife of a senior air force officer, after we heard the results of the Dresden attack. She was a well-educated and intelligent woman who worked part-time for the ORS. I asked her whether she really believed that it was right to kill German women and babies in large numbers at that late stage of the War. She answered, “Oh yes. It is good to kill the babies especially. I am not thinking of this war but of the next one, 20 years from now. The next time the Germans start a war and we have to fight them, those babies will be the soldiers.” After fighting Germans for ten years, four in the first war and six in the second, we had become almost as bloody-minded as Sir Arthur.

At last, at the end of April 1945, the order went out to the squadrons to stop offensive operations. Then the order went out to fill the bomb bays of our bombers with food packages to be delivered to the starving population of the Netherlands. I happened to be at one of the 3 Group bases at the time and watched the crews happily taking off on their last mission of the War, not to kill people but to feed them.

Freeman Dyson was for many years professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He is famous for his contributions to mathematical physics, particularly for his work on quantum electrodynamics. He was awarded the Lorentz Medal in 1966 and the Max Planck Medal in 1969, both for his contributions to modern physics. In 2000, he was awarded the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion.

A Failure of Intelligence: Part II

Prominent physicist Freeman Dyson recalls the time he spent developing analytical methods to help the British Royal Air Force bomb German targets during World War II.

by Freeman Dyson

Dec 5, 2006

Another job that Smeed gave me was to invent ways to estimate the effectiveness of various countermeasures, using all the evidence from a heterogeneous collection of operations. The first countermeasure that I worked on was MONICA. MONICA was a tail-mounted warning radar that emitted a high-pitched squeal over the intercom when a bomber had another aircraft close behind it. The squeals came more rapidly as the distance measured by the radar became shorter. The crews disliked MONICA because it was too sensitive and raised many false alarms. They usually switched it off so that they could talk to each other without interruption. My job was to see from the results of many operations whether MONICA actually saved lives. I had to compare the loss rates of bombers with and without MONICA. This was difficult because MONICA was distributed unevenly among the squadrons. It was given preferentially to Halifaxes (one of the two main types of British heavy bomber), which usually had higher loss rates, and less often to Lancaster bombers, which usually had lower loss rates. In addition, Halifaxes were sent preferentially on less dangerous operations and Lancasters on more dangerous operations. To use all the evidence from Halifax and Lancaster losses on a variety of operations, I invented a method that was later reinvented by epidemiologists and given the name “meta-analysis.” Assembling the evidence from many operations to judge the effectiveness of MONICA was just like assembling the evidence from many clinical trials to judge the effectiveness of a drug.

My method of meta-analysis was the following: First, I subdivided the data by operation and by type of aircraft. For example, one subdivision would be Halifaxes on Bremen on March 5; another would be Lancasters on Berlin on December 2. In each subdivision I tabulated the number of aircraft with and without MONICA and the number lost with and without MONICA. I also tabulated the number of MONICA aircraft expected to be lost if the warning system had no effect, and the statistical variance of that number. So I had two quantities for each subdivision: observed-minus-expected losses of MONICA aircraft, and the variance of this difference. I assumed that the distributions of losses in the various subdivisions were uncorrelated. Thus, I could simply add up the two quantities, observed-minus-expected losses and variance, over all the subdivisions. The result was a total observed-minus-expected losses and variance for all the MONICA aircraft, unbiased by the different fractions of MONICA aircraft in the various subdivisions. This was a sensitive test of effectiveness, making use of all the available information. If the total of observed-minus-expected losses was significantly negative, it meant that MONICA was effective. But instead, the total was slightly positive and less than the square root of the total variance. MONICA was statistically worthless. The crews had been right when they decided to switch it off.

I later applied the same method of analysis to the question of whether experience helped crews to survive. Bomber Command told the crews that their chances of survival would increase with experience, and the crews believed it. They were told, After you have got through the first few operations, things will get better. This idea was important for morale at a time when the fraction of crews surviving to the end of a 30-operation tour was only about 25 percent. I subdivided the experienced and inexperienced crews on each operation and did the analysis, and again, the result was clear. Experience did not reduce loss rates. The cause of losses, whatever it was, killed novice and expert crews impartially. This result contradicted the official dogma, and the Command never accepted it. I blame the ORS, and I blame myself in particular, for not taking this result seriously enough. The evidence showed that the main cause of losses was an attack that gave experienced crews no chance either to escape or to defend themselves. If we had taken the evidence more seriously, we might have discovered Schräge Musik in time to respond with effective countermeasures.

Smeed and I agreed that Bomber Command could substantially reduce losses by ripping out two gun turrets, with all their associated hardware, from each bomber and reducing each crew from seven to five. The gun turrets were costly in aerodynamic drag as well as in weight. The turretless bombers would have flown 50 miles an hour faster and would have spent much less time over Germany. The evidence that experience did not reduce losses confirmed our opinion that the turrets were useless. The turrets did not save bombers, because the gunners rarely saw the fighters that killed them. But our proposal to rip out the turrets went against the official mythology of the gallant gunners defending their crewmates. Dickins never had the courage to push the issue seriously in his conversations with Harris. If he had, Harris might even have listened, and thousands of crewmen might have been saved.

The part of his job that Smeed enjoyed most was interviewing evaders. Evaders were crew members who had survived being shot down over German-occupied countries and made their way back to England. About 1 percent of all those shot down came back. Each week, Smeed would go to London and interview one or two of them. Sometimes he would take me along. We were not supposed to ask them questions about how they got back, but they would sometimes tell us amazing stories anyway. We were supposed to ask them questions about how they were shot down. But they had very little information to give us about that. Most of them said they never saw a fighter and had no warning of an attack. There was just a sudden burst of cannon fire, and the aircraft fell apart around them. Again, we missed an essential clue that might have led us to Schräge Musik.

On November 18, 1943, Sir Arthur Harris started the Battle of Berlin. This was his last chance to prove the proposition that strategic bombing could win wars. He announced that the Battle of Berlin would knock Germany out of the War. In November 1943, Harris’s bomber force was finally ready to do what it was designed to do: smash Hitler’s empire by demolishing Berlin. The Battle of Berlin started with a success, like the first attack on Hamburg on July 24. We attacked Berlin with 444 bombers, and only 9 were lost. Our losses were small, not because of WINDOW, but because of clever tactics. Two bomber forces were out that night, one going to Berlin and one to Mannheim. The German controllers were confused and sent most of the fighters to Mannheim.

After that first attempt on Berlin, Sir Arthur ordered 15 more heavy attacks, expecting to destroy that city as thoroughly as he had destroyed Hamburg. All through the winter of 1943 and ‘44, the bombers hammered away at Berlin. The weather that winter was worse than usual, covering the city with cloud for weeks on end. Our photoreconnaissance planes could bring back no pictures to show how poorly we were doing. As the attacks went on, the German defenses grew stronger, our losses heavier, and the “scatter” of the bombs worse. We never raised a firestorm in Berlin. On March 24, in the last of the 16 attacks, we lost 72 out of 791 bombers, a loss rate of 9 percent, and Sir Arthur admitted defeat. The battle cost us 492 bombers with more than 3,000 aircrew. For all that, industrial production in Berlin continued to increase, and the operations of government were never seriously disrupted.

There were two main reasons why Germany won the Battle of Berlin. First, the city is more modern and less dense than Hamburg, spread out over an area as large as London with only half of London’s population; so it did not burn well. Second, the repeated attacks along the same routes allowed the German fighters to find the bomber stream earlier and kill bombers more efficiently.

A week after the final attack on Berlin, we suffered an even more crushing defeat. We attacked Nuremberg with 795 bombers and lost 94, a loss rate of almost 12 percent. It was then clear to everybody that such losses were unsustainable. Sir Arthur reluctantly abandoned his dream of winning the War by himself. Bomber Command stopped flying so deep into Germany and spent the summer of 1944 giving tactical support to the Allied armies that were, by then, invading France.

The history of the 20th century has repeatedly shown that strategic bombing by itself does not win wars. If Britain had decided in 1936 to put its main effort into building ships instead of bombers, the invasion of France might have been possible in 1943 instead of 1944, and the war in Europe might have ended in 1944 instead of 1945. But in 1943, we had the bombers, and we did not have the ships, and the problem was to do the best we could with what we had.

One of our group of young students at the ORS was Sebastian Pease, known to his friends as Bas. He had joined the ORS only six months before I had, but by the time I got there, he already knew his way around and was at home in that alien world. He was the only one of us who was actually doing what we were all supposed to be doing: helping to win the War. The rest of us were sitting at Command Headquarters, depressed and miserable because our losses of aircraft and aircrew were tremendous and we were unable to do much to help. The Command did not like it when civilians wandered around operational squadrons collecting information, so we were mostly confined to our gloomy offices at the headquarters. But Bas succeeded in breaking out. He spent most of his time with the squadrons and came back to headquarters only occasionally. Fifty years later, when he was visiting Princeton (where I spent most of my life, working as a professor of physics), he told me what he had been doing.

Bas was able to escape from Command Headquarters because he was the expert in charge of a precise navigation system called G-H. Only a small number of bombers were fitted with G-H, because it required two-way communication with ground stations. These bombers belonged to two special squadrons, 218 Squadron being one of them. The G-H bombers were Stirlings, slow and ponderous machines that were due to be replaced by the smaller and more agile Lancasters. They did not take part in mass-bombing operations with the rest of the Command but did small, precise operations on their own with very low losses. Bas spent a lot of time at 218 Squadron and made sure that the G-H crews knew how to use their equipment to bomb accurately. He had “a good war,” as we used to say in those days. The rest of us were having a bad war.

Sometime early in 1944, 218 Squadron stopped bombing and started training for a highly secret operation called GLIMMER, which Bas helped to plan, and whose purpose was to divert German attention from the invasion fleet that was to invade France in June. The operation was carried out on the night of June 5-6. The G-H bombers flew low, in tight circles, dropping WINDOW as they moved slowly out over the English Channel. In conjunction with boats below them that carried specially designed radar transponders, they appeared to the German radars to be a fleet of ships. While the real invasion fleet was moving out toward Normandy, the fake invasion fleet of G-H bombers was moving out toward the Pas de Calais, 200 miles to the east. The ruse was successful, and the strong German forces in the Pas de Calais did not move to Normandy in time to stop the invasion. While Bas was training the crews, he said nothing about it to his friends at the ORS. We knew only that he was out at the squadrons doing something useful. Even when GLIMMER was over and the invasion had succeeded, Bas never spoke about it. My boss, Reuben Smeed, was a man of considerable wisdom. One day at Bomber Command, he said, “In this business, you have a choice. Either you get something done or you get the credit for it, but not both.” Bas’s work was a fine example of Smeed’s dictum. He made his choice, and he got something done. In later life he became a famous plasma physicist and ran the Joint European Torus, the main fusion program of the European Union.

The one time that I did something practically useful for Bomber Command was in spring 1944, when Smeed sent me to make accurate measurements of the brightness of the night sky as a function of time, angle, and altitude. The measurements would be used by our route planners to minimize the exposure of bombers to the long summer twilight over Germany. I went to an airfield at the village of Shawbury in Shropshire and flew for several nights in an old Hudson aircraft, unheated and unpressurized. The pilot flew back and forth on a prescribed course at various altitudes, while I took readings of sky brightness through an open window with an antiquated photometer, starting soon after sunset and ending when the sun was 18 degrees below the horizon. I was surprised to find that I could function quite well without oxygen at 20,000 feet. I shared this job with J. F. Cox, a Belgian professor who was caught in England when Hitler overran Belgium in 1940. Cox and I took turns doing the measurements. My flights were uneventful, but on the last of Cox’s flights, both of the Hudson’s engines failed, and the pilot decided to bail out. Cox also bailed out and came to earth still carrying the photometer. He broke an ankle but saved the device. In later years, he became rector of the Free University in Brussels.

After the War, Smeed worked for the British government on road traffic problems and then taught at University College London, where he was the first professor of traffic studies. He applied the methods of operational research to traffic problems all over the world and designed intelligent traffic-light control systems to optimize the flow of traffic through cities. Smeed had a fatalistic view of traffic flow. He said that the average speed of traffic in central London would always be nine miles per hour, because that is the minimum speed that people will tolerate. Intelligent use of traffic lights might increase the number of cars on the roads but would not increase their speed. As soon as the traffic flowed faster, more drivers would come to slow it down.

Smeed also had a fatalistic view of traffic accidents. He collected statistics on traffic deaths from many countries, all the way back to the invention of the automobile. He found that under an enormous range of conditions, the number of deaths in a country per year is given by a simple formula: number of deaths equals .0003 times the two-thirds power of the number of people times the one-third power of the number of cars. This formula is known as Smeed’s Law. He published it in 1949, and it is still valid 57 years later. It is, of course, not exact, but it holds within a factor of two for almost all countries at almost all times. It is remarkable that the number of deaths does not depend strongly on the size of the country, the quality of the roads, the rules and regulations governing traffic, or the safety equipment installed in cars. Smeed interpreted his law as a law of human nature. The number of deaths is determined mainly by psychological factors that are independent of material circumstances. People will drive recklessly until the number of deaths reaches the maximum they can tolerate. When the number exceeds that limit, they drive more carefully. Smeed’s Law merely defines the number of deaths that we find psychologically tolerable.

The last year of the War was quiet at ORS Bomber Command. We knew that the War was coming to an end and that nothing we could do would make much difference. With or without our help, Bomber Command was doing better. In the fall of 1944, when the Germans were driven out of France, it finally became possible for our bombers to make accurate and devastating night attacks on German oil refineries and synthetic-oil-production plants. We had long known these targets to be crucial to Germany’s war economy, but we had never been able to attack them effectively. That changed for two reasons. First, the loss of France made the German fighter defenses much less effective. Second, a new method of organizing attacks was invented by 5 Group, the most independent of the Bomber Command groups. The method originated with 617 Squadron, one of the 5 Group squadrons, which carried out the famous attack on the Ruhr dams in March 1943. The good idea, as usually happens in large organizations, percolated up from the bottom rather than trickling down from the top. The approach called for a “master bomber” who would fly a Mosquito at low altitude over a target, directing the attack by radio in plain language. The master bomber would first mark the target accurately with target indicator flares and then tell the heavy bombers overhead precisely where to aim. A deputy master bomber in another Mosquito was ready to take over in case the first one was shot down. Five Group carried out many such precision attacks with great success and low losses, while the other groups flew to other places and distracted the fighter defenses. In the last winter of the War, the German army and air force finally began to run out of oil. Bomber Command could justly claim to have helped the Allied armies who were fighting their way into Germany from east and west.

While the attacks on oil plants were helping to win the War, Sir Arthur continued to order major attacks on cities, including the attack on Dresden on the night of February 13, 1945. The Dresden attack became famous because it caused a firestorm and killed a large number of civilians, many of them refugees fleeing from the Russian armies that were overrunning Pomerania and Silesia. It caused some people in Britain to question the morality of continuing the wholesale slaughter of civilian populations when the War was almost over. Some of us were sickened by Sir Arthur’s unrelenting ferocity. But our feelings of revulsion after the Dresden attack were not widely shared. The British public at that time still had bitter memories of World War I, when German armies brought untold misery and destruction to other people’s countries, but German civilians never suffered the horrors of war in their own homes. The British mostly supported Sir Arthur’s ruthless bombing of cities, not because they believed that it was militarily necessary, but because they felt it was teaching German civilians a good lesson. This time, the German civilians were finally feeling the pain of war on their own skins.

I remember arguing about the morality of city bombing with the wife of a senior air force officer, after we heard the results of the Dresden attack. She was a well-educated and intelligent woman who worked part-time for the ORS. I asked her whether she really believed that it was right to kill German women and babies in large numbers at that late stage of the War. She answered, “Oh yes. It is good to kill the babies especially. I am not thinking of this war but of the next one, 20 years from now. The next time the Germans start a war and we have to fight them, those babies will be the soldiers.” After fighting Germans for ten years, four in the first war and six in the second, we had become almost as bloody-minded as Sir Arthur.

At last, at the end of April 1945, the order went out to the squadrons to stop offensive operations. Then the order went out to fill the bomb bays of our bombers with food packages to be delivered to the starving population of the Netherlands. I happened to be at one of the 3 Group bases at the time and watched the crews happily taking off on their last mission of the War, not to kill people but to feed them.

To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.

To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.