Only a few minutes before, President Eisenhower had rejected a last desperate plea written in her cell by Ethel Rosenberg. Mr Emanuel Bloch, the couple's lawyer, personally took the note to the White House where guards turned him away.

Neither of the two said anything before they died. The news of their execution was announced at 1.43 a.m. (British time).

President's statement

New York, June 19

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison tonight. Neither husband nor wife spoke before they died.

Julius Rosenberg, aged 35, was the first to die. They were executed just before the setting sun heralded the Jewish Sabbath. Prison officials had advanced the execution time to spare religious feelings.

Mrs Rosenberg turned just before she was placed in the electric chair, drew Mrs Evans, the prison matron towards her, and they kissed. The matron was visibly affected. She quickly turned and left the chamber. In the corridor outside Rabbi Irving Koslowe could be heard intoning the 23rd Psalm.

The couple were the first civilians in American history to be executed for espionage. They were sentenced to death on April 5, 1951, for passing on atomic secrets to Russia during the Second World War.

Eisenhower's statement

The last hope of reprieve for the Rosenbergs vanished early this afternoon when President Eisenhower rejected a final appeal for clemency shortly after the Supreme Court had set aside the stay of execution granted by Justice Douglas, one of its own members on Monday. The President's decision was announced in the following statement from the White House:

"Since the original review of proceedings in the Rosenberg case by the Supreme Court of the United States, the courts have considered numerous further proceedings challenging the Rosenbergs conviction and the sentencing involved. Within the last two days, the Supreme Court convened in a special session and reviewed a further point which one of the justices felt the Rosenbergs should have an opportunity to present. This morning the Supreme Court ruled that there was no substance to this point.

I am convinced that the only conclusion to be drawn from the history of this case is that the Rosenbergs have received the benefits of every safeguard which American justice can provide. There is no question in my mind that their original trial and the long series of appeals constitute the fullest measure of justice and due process of law. Throughout the innumerable complications and technicalities of this case no Judge has ever expressed any doubt that they committed most serious acts of espionage.

Accordingly, only most extraordinary circumstances would warrant Executive intervention in the case. I am not unmindful of the fact that this case has aroused grave concern both here and abroad in the minds of serious people aside from the considerations of law. In this connection I can only say that, by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world. The execution of two human beings is a grave matter. But even graver is the thought of millions of dead, whose death may be directly attributable to what these spies have done.

When democracy's enemies have been judged guilty of a crime as horrible as that of which the Rosenbergs were convicted: when the legal processes of democracy have been marshalled to their maximum strength to protect the lives of convicted spies: when in their most solemn judgement the tribunals of the United States has adjudged them guilty and the sentence just. I will not intervene in this matter. "

"So much doubt"

President Eisenhower's decision came about half an hour after Mr Emanuel Bloch, the Rosenberg's chief lawyer, had addressed an impassioned appeal to him, declaring that the world would be shocked if the execution was carried out with, he said, so much doubt in the case. He demanded that the President should find himself time "to consider this serious matter" and argued that rejection of the clemency appeal would jeopardise the United State's relation with its allies. "Tens of millions throughout the world condemn the death sentence" he added. "For the sake of American tradition, prestige and influence I urge redress for the Rosenbergs."

Less than four hours before the execution, Mr Bloch announced the failure of yet another attempt to gain a stay - a separate plea to Justice Burton, one of nine members of the Supreme Court - to Reuter and British United Press.

Prime Minister asked to intercede

A deputation from a "Save the Rosenbergs" protest meeting held at Marble Arch, London last night, called at No.10 Downing Street where it was told the Prime Minister was at Chartwell. Members of the deputation, which was led by the Rev. Stanley Evans, then motored to Chartwell.

When they arrived in the lane outside Sir Winston's home, Mr Evans and Professor Bernal found about twenty supporters of the National Rosenberg Defence Committee. They had scribbled a note addressed "Dear P.M.," and asking the Prime Minister to appeal direct "to President Eisenhower over the Transatlantic telephone immediately." In reply they received a typewritten note saying: "It is not within my duty or my power to intervene in this matter. (Signed) Winston Churchill."

This reply was handed to the deputation at midnight, and the gates of Chartwell were closed for the night.

In London, fifty demonstrators who had earlier stated they intended to keep an all-night vigil at No.10 Downing Street found police had cordoned off both entrances by the time they arrived at 12.50 a.m.

At one o'clock this morning in Manchester a crowd of two hundred stood quietly outside the offices of the "Manchester Guardian" waiting for news of the Rosenberg executions.

The crowd stood in silence until the executions were announced at 1.45 a.m. The news was received in silence, and members of the crowd, most of them men, maintained a two minutes' silence for the Rosenbergs. Afterwards they moved off to the steps of the Royal Exchange in Cross Street where the meeting pledged itself to continue the fight to clear the name of the Rosenbergs and "to pin the blame where it rightly belongs."

A telegram sent earlier to the Queen had asked her to use her influence towards securing a reprieve.

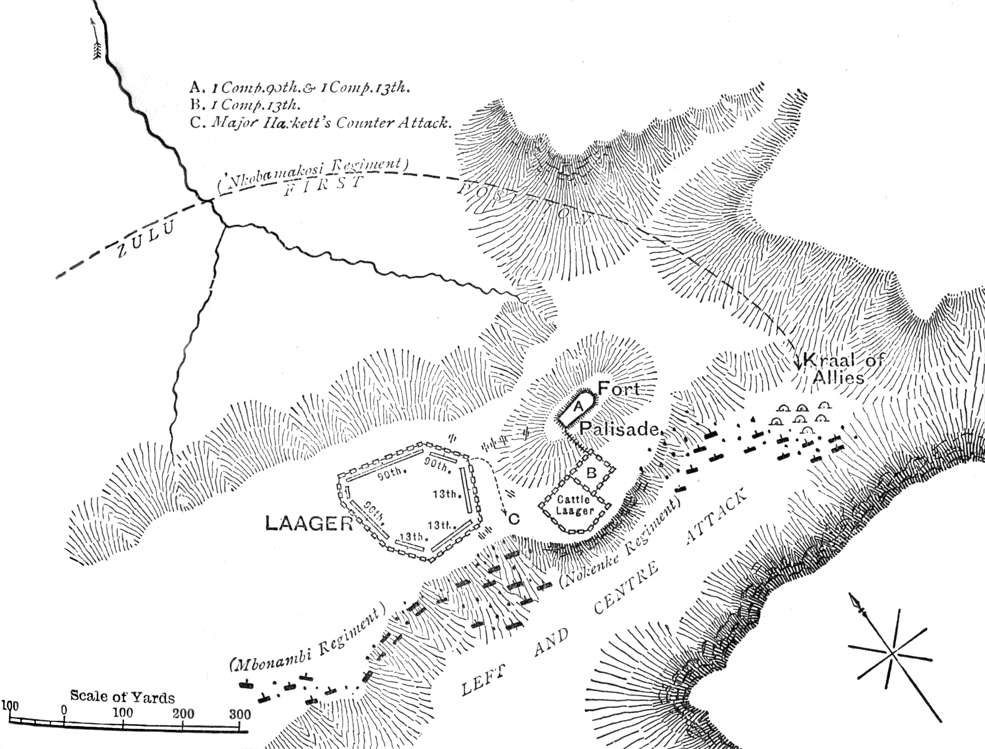

© David Goldman/AP

© David Goldman/AP